Shanghai

Exiles, Art and Urban Sites during War

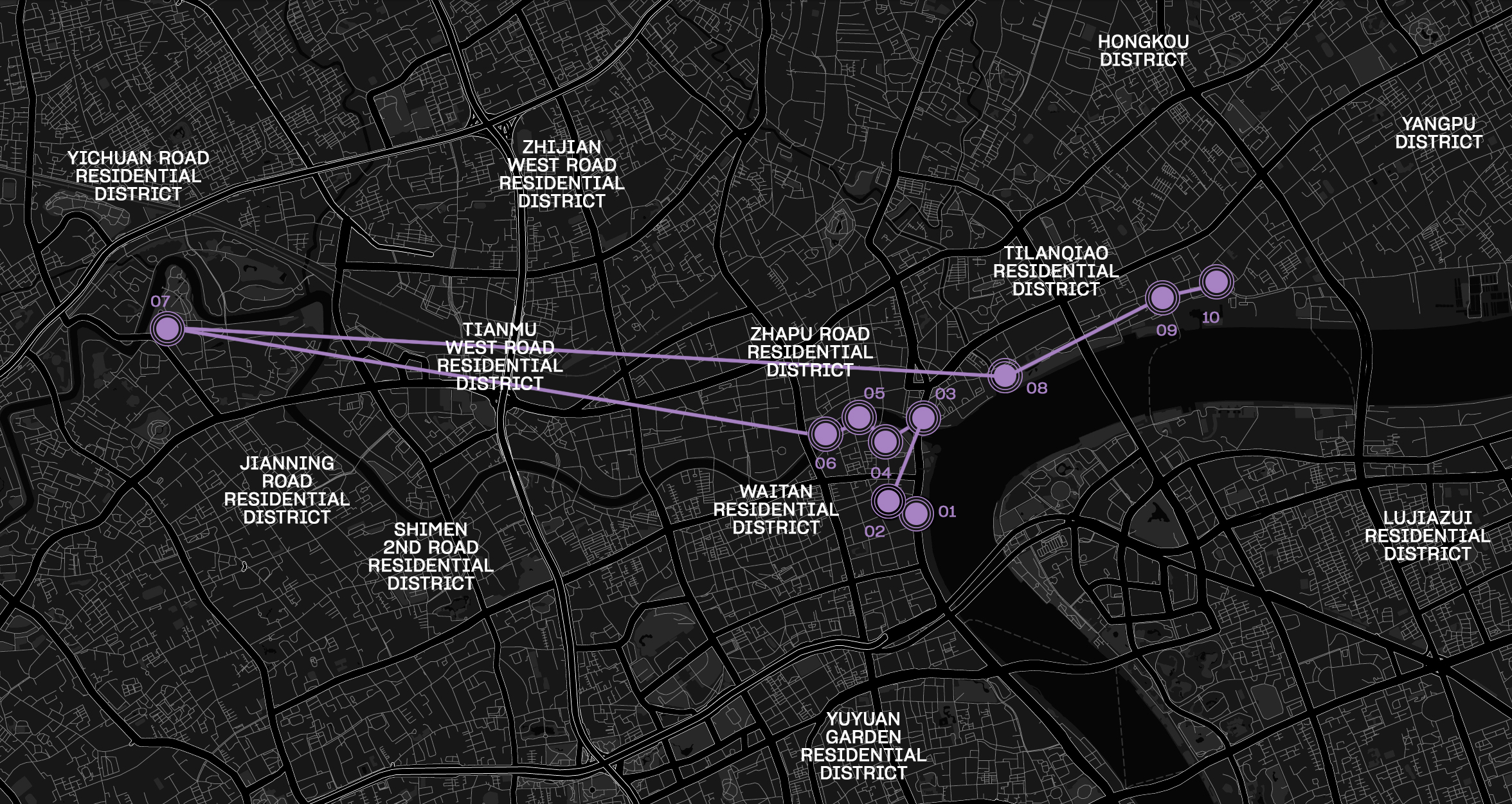

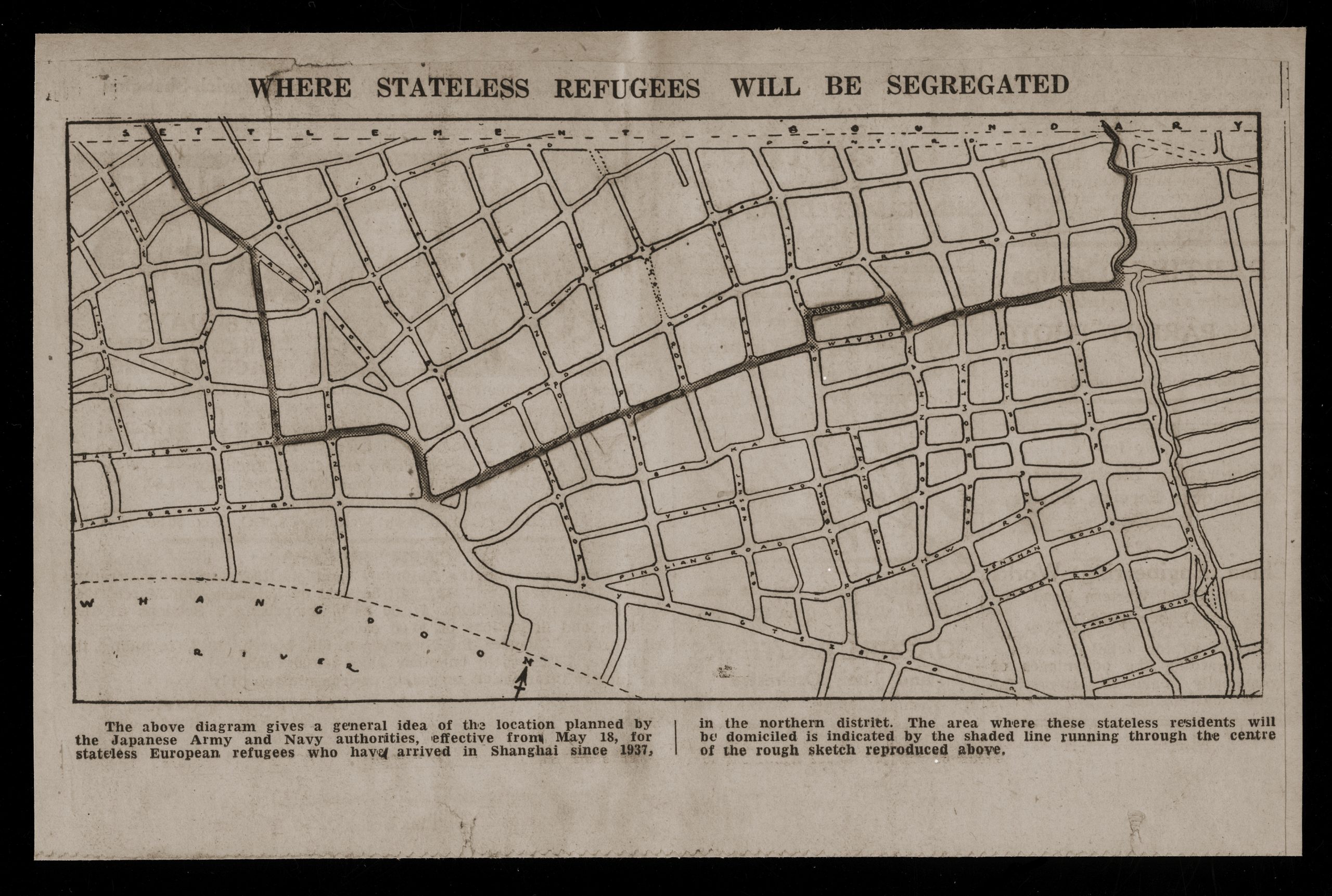

The Shanghai walk roughly follows a route taken by the German-Jewish refugee, theatre maker and journalist Alfred Dreifuß (1902–1993). On board the Conte Verde he landed on Shanghai’s riverbanks in June 1939. Four months later, in an article entitled “Broadway Melody”, he remembers his arrival while walking from the Bund into the heart of Little Vienna, later to be known as the so-called Shanghai Ghetto Not least because of the complex political and administrative situation in Shanghai, there was no effective visa control. The largest community of ‘floating people’, second only to the Chinese, consisted of Russians who had fled their country in the wake of the founding of the Soviet Union in 1922. Around 1937–1941, about 20 000 European refugees fleeing Nazi persecution (estimates vary up to 30 000) reached Shanghai. In 1943, already declared as “stateless” by the Nazi Regime, most of them were forced into a small, designated area in Hongkou.

Dreifuß describes the changing urban landscape and its population, the climate, smells and sounds of his surroundings. His sensual perception is layered with memories of what has been left behind and with unfulfilled expectations, with reflections of his exile conditions and with thinking towards an uncertain future. His text touches trajectories of urban and cultural imaginaries collapsing and transforming while dealing with the unknown.

The route presented here – compiled more than 80 years later – takes not only into account his perspective, but also other sites related to art and exile, while tracing their remaining fragments that have defied the immense transformation of the city.

miles 150

min. 10

sights By foot and metro

01Bund/ corner Nanjing Road, Huangpu

Broadway Melody by Alfred Dreifuß read by Luana Velis.

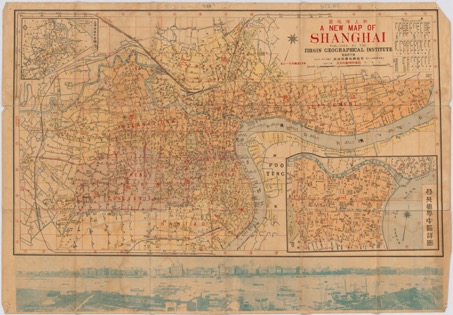

A New Map of Shanghai, JIH-SIN Geographical Institute, pauli-44-4 (© Architektur Museum der TU München).

The map shows Shanghai’s different urban and national territories. The eastern part of the city is bordered by the Huangpu River. The Bund is located on the west bank of the Huangpu River south of Suzhou Creek. North of Suzhou Creek stretches Hongkou, an urban area comprehensively controlled by the Japanese since 1937. In eastern Hongkou, near the Huangpu River, the so-called Shanghai Ghetto was built by the Japanese in 1943.

A map from the North China Daily News showing the borders of the zone to which stateless refugees were confined from February 1943 on (© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eric Goldstaub).

A little ahead of Dreifuß, the Shanghai Walk begins in the former International Settlement at the Bund where Nanjing Road, formerly Nanking Road, begins.

The Bund is often characterized as the former seat of colonial and financial power. It greeted the newly arrived with his distinctive large-scale architecture which differed sharply from environment and facilities the majority of Jewish European refugees were brought to shortly afterwards. Nanking Road was and is still one of the busiest streets in Shanghai and featured many art venues and photo studio ran by émigrés.

As a semi-colonial city, a consequence of the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, Shanghai’s urban area was divided into different national territories. The Chinese districts, the International Settlement and the French Concession were successively seized by the Japanese military after the so-called Battle of Shanghai (1932) and during the so-called Second Sino Japanese War (1937–1945). By then, the city had already suffered through relentless fights on the ground, bomb damage (mainly in Zhabei and Hongkou) and high numbers of civil casualties. The war caused massive interurban flight movements into the parts of the city not yet controlled by the Japanese but also, for those who could afford to, out of the city. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Japanese began to intern their enemy aliens and the former commerce and business life came to a standstill. Of Shanghai’s population approximately 80% were fugitives. After the fall of the First United Front, also known as the GMD–CPC Alliance (1923–1927), leftist activists, intellectuals, writers and artists sought a rather short-termed refuge in the foreign territories of the city before the majority fled inland to escape the advancing Japanese military.

Malcom Rosholt, The Bund, Shanghai, around 1937 (© 2012 Mei-Fei Elrick and Tess Johnston, University of Bristol, www.hpcbristol.net).

Malcolm Rosholt (1907–2005) stayed in China from 1931 to 1937 and from 1943 to 1945. He covered the wars, first as a reporter and then as an Intelligence Office for the Fourteenth Air Force.

Malcom Rosholt, Evacuees waiting to leave, The Bund, Shanghai, around 1937 (© 2012 Mei-Fei Elrick and Tess Johnston, University of Bristol, www.hpcbristol.net).

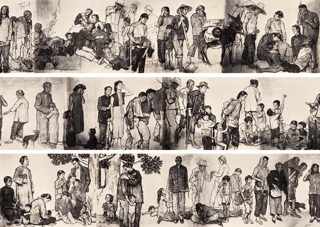

Photograph of the lost part of Jiang Zhaohe’s (1904–1986) Liumin Tu, 1943.

The other half was rediscovered damaged in a warehouse in Shanghai in 1953.

The originally 26 m long and 2 m high scroll went missing after it had been shown in the French Concession in 1944 and taken by the Japanese afterwards. The title liumin has been translated in different ways, often as ‘refugeesʼ, but also as ‘homeless peopleʼ. The scroll is part of a long genre tradition of paintings depicting liumin. The term is accompanied by a variety of alterations and historically refers to peasant refugees who fled in high numbers or in whole village communities to escape natural disasters or oppression: min refers to a group of people rather than to an individual. The term can be also used in exile contexts and liuren can be translated as ‘a person living in exileʼ. The character liu can be translated as ‘a stream of waterʼ or, in combination with min or ren, as ‘floatingʼ.

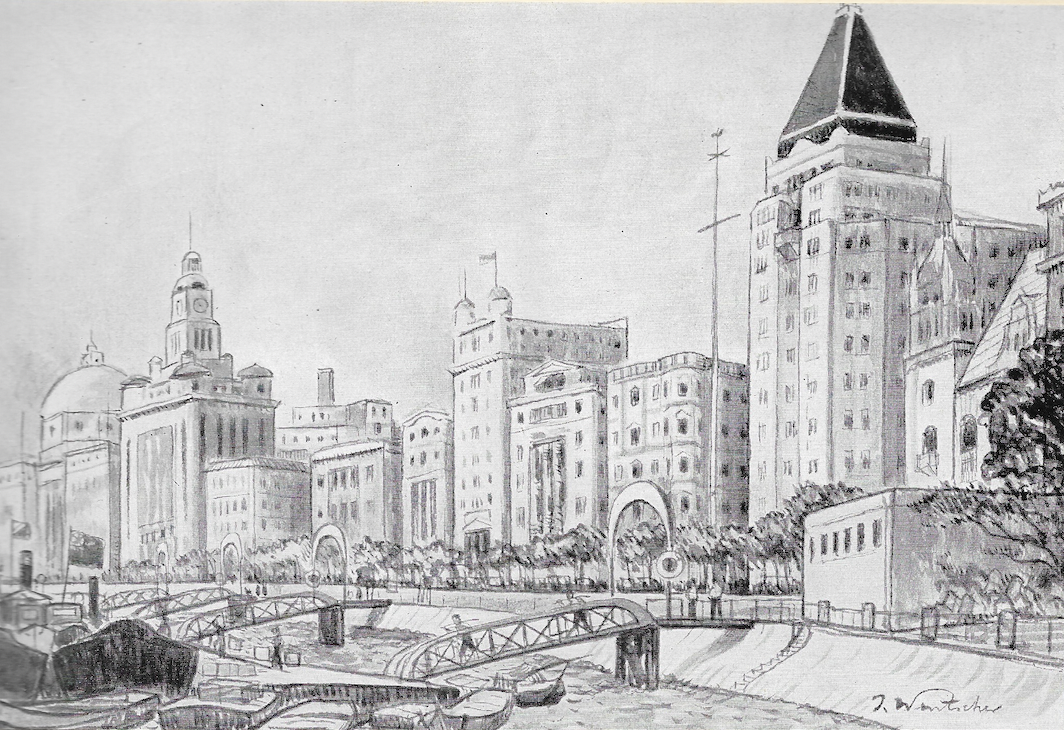

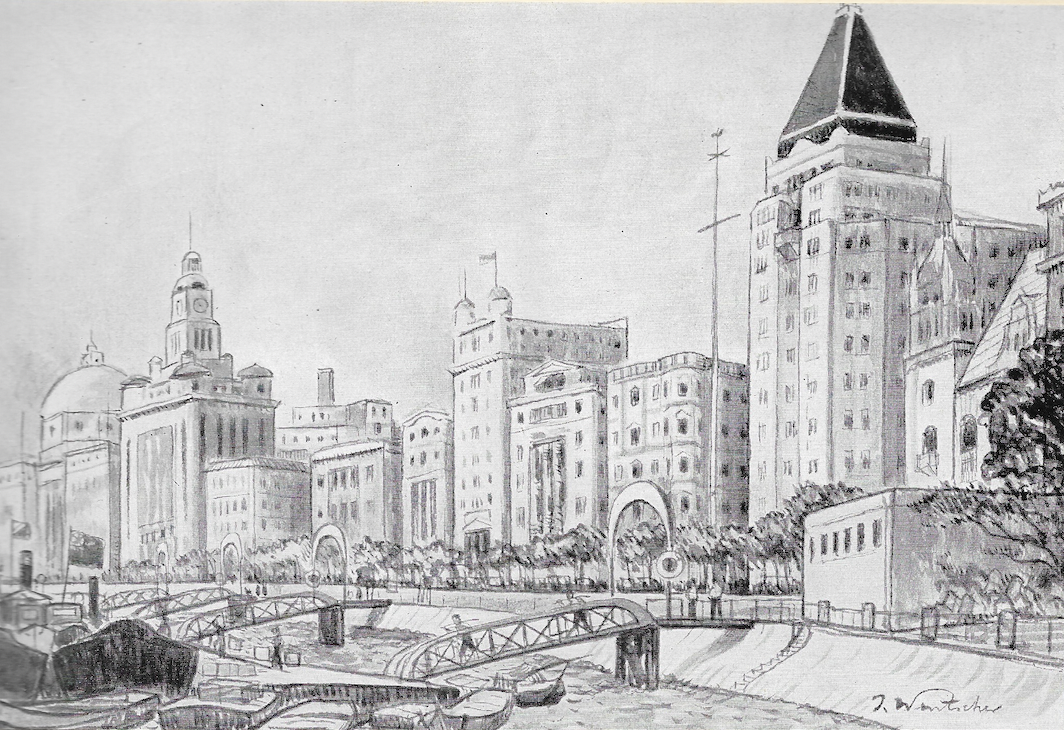

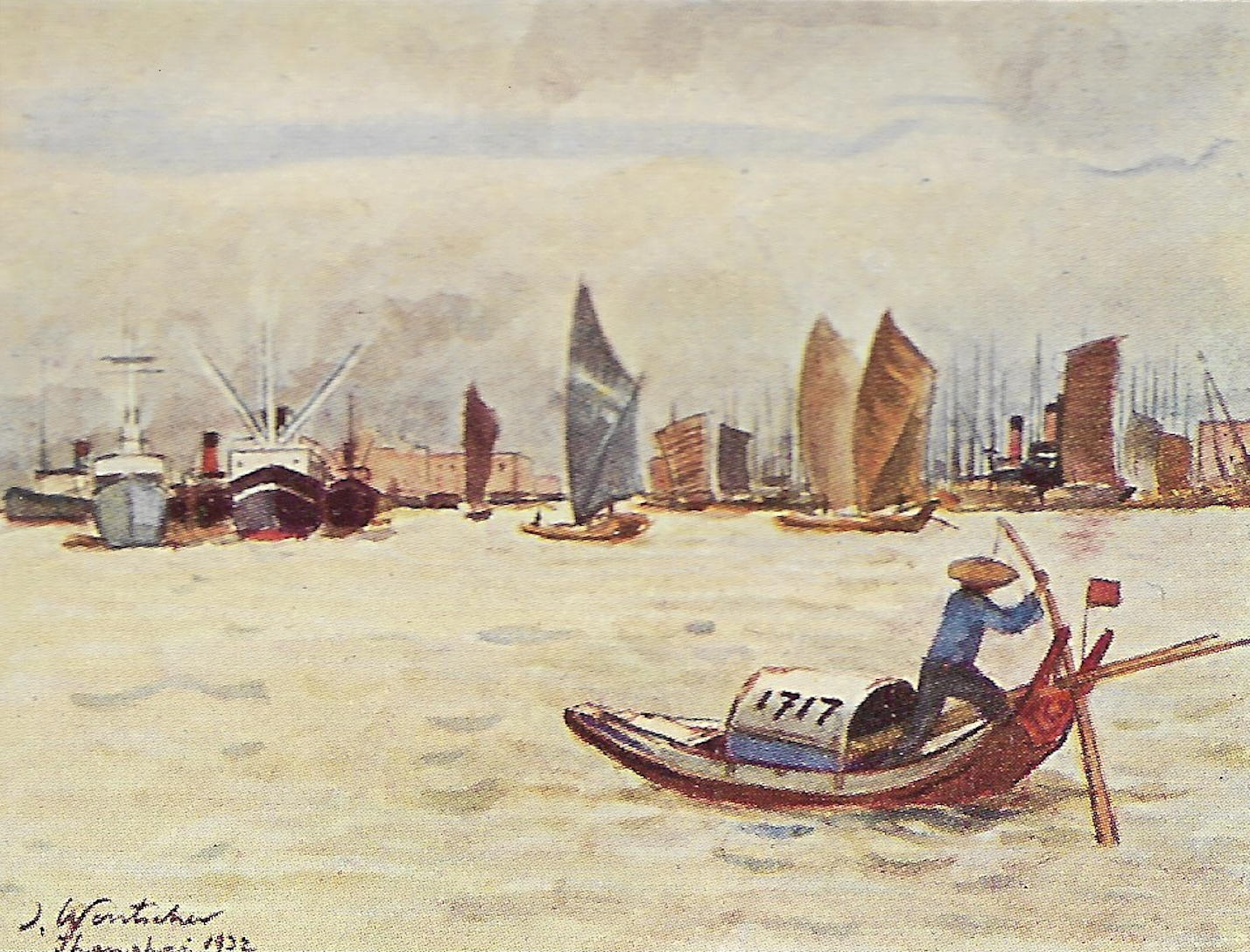

Julius Wentcher, Bund, China Het Rijk Van Het Midden. Koninklijeke Drukkerijen G. Kolff & Co., Batavia–C., 1933.

02Fairmont Peace Hotel (former Sassoon House and Cathay Hotel)/ 20 Nanjing East Road, Huangpu

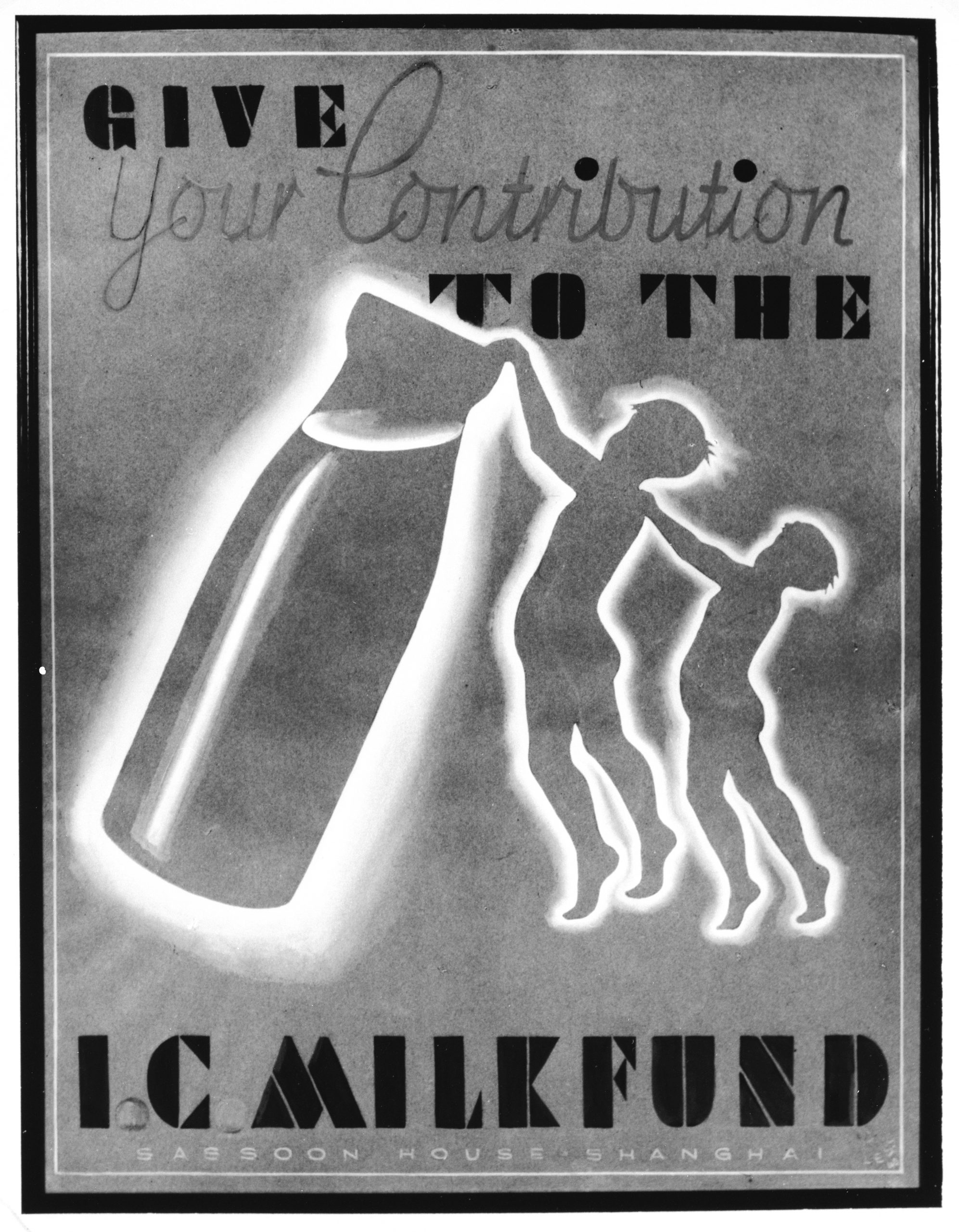

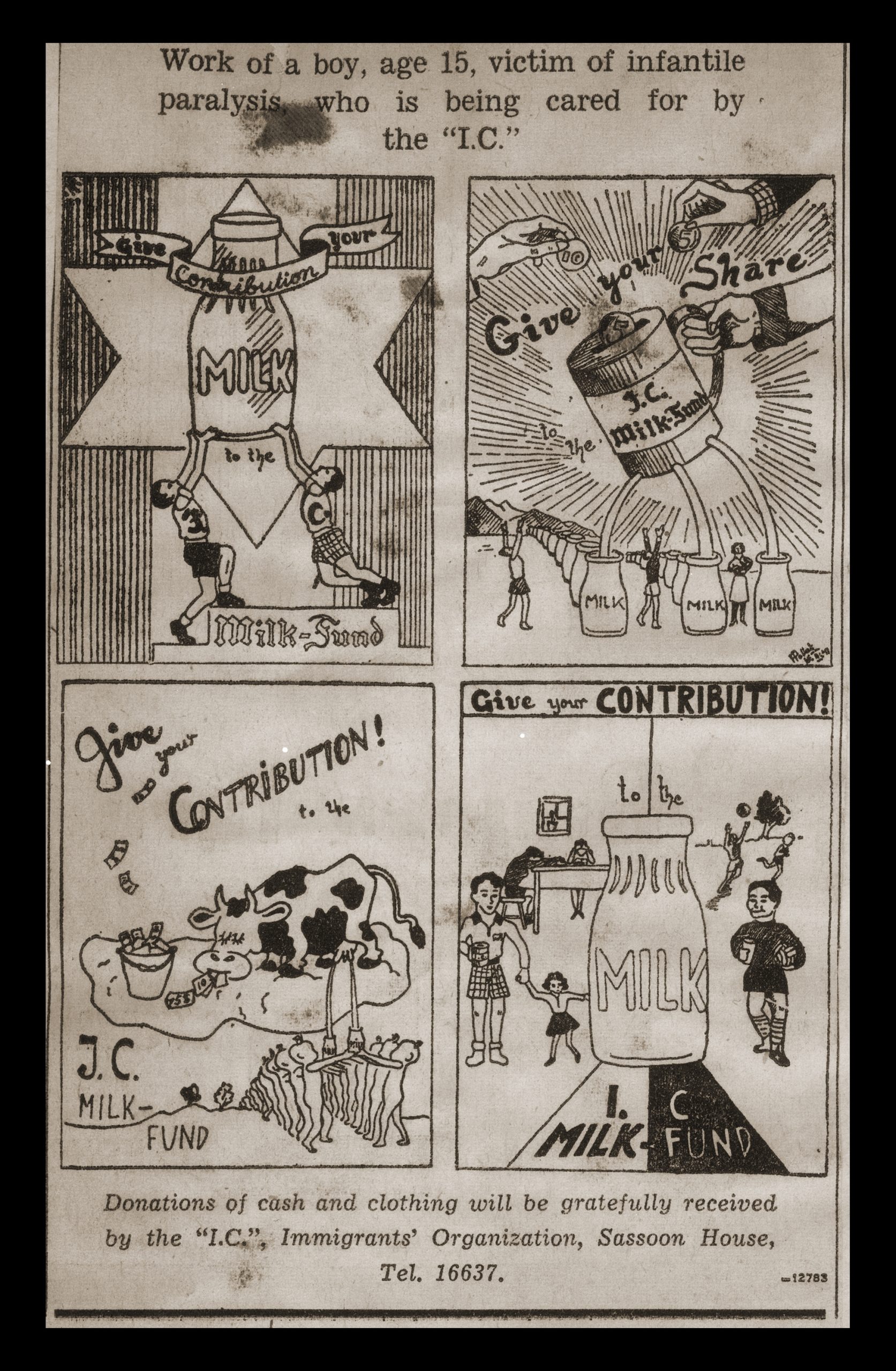

On the corner of Nanking Road and the Bund stands Fairmont Peace Hotel, formerly known as the Sassoon Building and Cathay Hotel and also a well-known address among the émigré communities. Commissioned and owned by Sir Ellice Victor Sassoon, third Baronet of Bombay (1881–1961), the large art deco building was designed and completed in 1929 by the well-known Shanghainese architectural and engineering firm Palmer and Turner. Sassoon, who came from a Baghdadi Jewish family, eventually moved his business interests from Bombay to Shanghai in the 1930s and turned the newly-built Sassoon House not only into a private residence but also into the headquarters of E.D. Sassoon & Co. Limited. Besides various office and leisure facilities, the building most prominently contained the luxurious Cathay Hotel with its famous Tower Night Club, Jazz Bar, restaurants and roof terrace where Shanghai’s tourists and its local and foreign elites gathered. In 1937, two errant bombs fell between the Cathay and Palace Hotel. This incident is narrated by Vicky Baum (1888–1960) in Hotel Shanghai, her 1937 novel which connected the comings and goings at a Grand Hotel to Shanghai’s diverse (refugee) urban environments. The book was published successively in a Jewish emigrant newspaper called 8-Uhr-Abendblatt (the former Shanghai Woche), edited by Wolfgang Fischer. From the late 1930s onwards, Sassoon House accommodated an emigrant’s thrift shop and the offices of the International Committee for European Immigrants (IC), founded in 1938 by Sassoon and Paul Komor. The IC’s task was to provide housing, work and financial assistance to European refugees. The Jewish Berlin-born artist Hans Less (1923–2001) designed several graphics for IC aid campaigns, such as the Milkfund. He arrived in Shanghai in 1940 and worked for an advertising studio in Shanghai.

Malcom Rosholt, Bank of China building under construction, The Bund, Shanghai, around 1937 (© 2012 Mei-Fei Elrick and Tess Johnston, University of Bristol, www.hpcbristol.net).

Hans Less, Fundraising poster for the Milk Fund of the International Committee for European Immigrants in Shanghai (© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Valerie S. Komor).

Cartoon advertisements from the North-China Daily News asking for donations to the Milk Fund of the International Committee for the Organization of European Immigrants in China (© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eric Goldstaub).

Eric Goldstaub received 20 visa for his family issued by the Chinese consul general Ho Feng Shan (1901–997) in Vienna. Resisting attempts by the Nazis to stop him, Ho Feng Shan executed an effective visa issuing production, saving thousands of lives.

Advertisement, Emigrant’s Thrift Shop, Die Tribüne, vol. 8, 1940, p. 280.

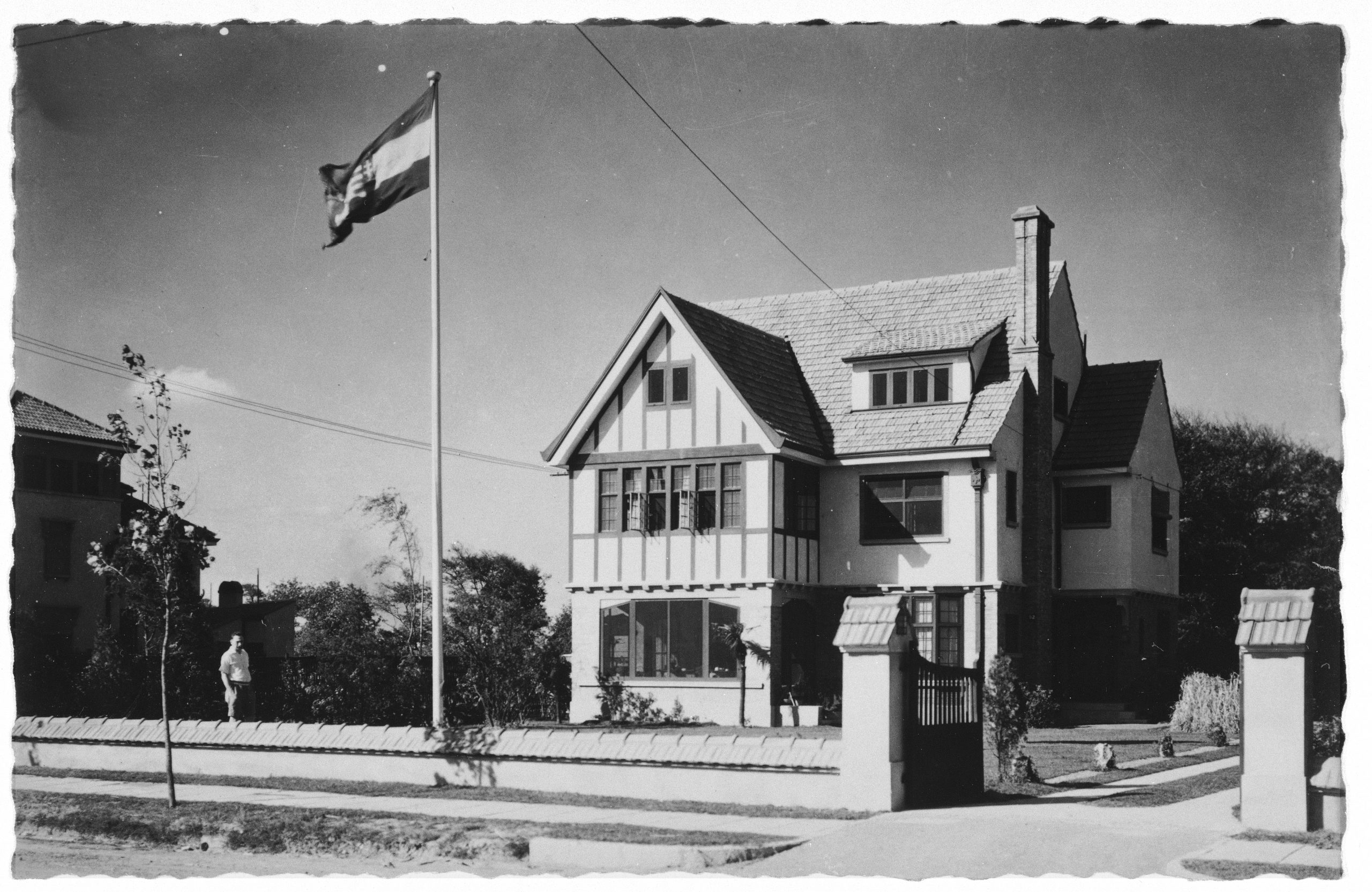

A Hungarian flag flies in front of the residence of the Komor family at 92 Amherst Road in Shanghai. Designed by Hungarian architect Wladislaus Hudec, the Komor home was built in 1929 (© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Valerie S. Komor).

Paul Komor (1886 –1973) was the Honorary Consul for Hungary until he was arrested by the Japanese in 1942. Hudec became his successor. Among others, Komor founded the International Committee for European Immigrants (IC), funded by Victor Sassoon, in 1938.

Little is known about some of the other venues and art spaces also located at the Sassoon building, such as the Pelican Nightclub, The Studio or the Phoenix Gallery. The Studio was an art showroom operated by two Germans, most prominently by the exiled architect Richard Paulick (1903–1979). Together with his younger brother Rudolf Paulick (1908–1966) and two friends he arrived in Shanghai in 1933 with the help of his friend and colleague Rudolf Hamburger (1903–1980). Hamburger went to Shanghai already in 1930 after having successfully applied as architect at the Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC). Hamburger was already well connected an ran an interior design firm the modern home where both Paulicks began to work. In 1934 Victor Sassoon entered the business and opened Modern Homes where the two brothers continued to work. Sassoon would use the new business for his various construction projects throughout the city until 1936. Both Paulicks set up further businesses. Their interior designs encompassed a range of styles that reflected the various tastes of the urban bourgeoisie and elite. These designs were documented by several photo studios. Most of them were led by émigrés, such as Skvirsky’s Studio on Nanking Road which was also where Sassoon pursued his amateur photography. Others were the formerly Budapest, Berlin and Viennese based photo enterprise Willinger & Co or Nini Studio on 469 Bubbling Well Road, Rembrandt-Studio at Hamilton House, Room 128 or Bann’s Studio at 104 Bubbling Well Road that was founded in 1927 by Peng Wangshi. The latter is known for its military portraits of GMD and RNG officials and had a branch in Nanjing.

Schiff, Friedrich and Ellen Thorbecke. Shanghai. North China Daily News & Herald Ltd, 1941, p. 34.

Richard Paulick, Firma Modern Homes R. Sands Furnishing, Café Europe, pauli–22–1017 (© Architektur Museum der TU München).

Probably photographed by Rembrandt Studio at Hamilton House.

Richard Paulick, Firma Modern Homes R. Sands Furnishing, Café Europe Interior, pauli–22–1020 (© Architektur Museum der TU München).

Photographed by Rembrandt Studio at Hamilton House.

Richard Paulick, Firma Modern Homes R. Sands Furnishing, Café Europe Interior, pauli–22–1021 (© Architektur Museum der TU München).

Photographed by Rembrandt Studio at Hamilton House.

Richard Paulick, Firma Modern Homes R. Sands Furnishing, Café Europe, Interior, pauli–22–1019 (© Architektur Museum der TU München).

Photographed by Rembrandt Studio at Hamilton. The wall paintings show different architectures and costumes associated with various European countries. Wall paintings were in fashion, not only as a distinct and competitive feature of restaurants, cafés, bars and nightclubs, but also in private residencies.

Richard Paulick, Firma Modern Homes Sands Furnishing Interior, pauli–22_1022 (© Architektur Museum der TU München).

Photographed by Skvirsky Studio. This interior reflects a rather conservative and bourgeoise taste.

The Studio, which likely opened in 1942, featured various art and craft exhibitions, among them five shows by Friedrich Schiff (1908–1968), in 1943, an exhibition of rose oil paintings by Ito Kenshi (1907–1978), a member of the Nika-kai Association (1914) or, it exhibited prints of the Austrian born émigré artist Emma Bormann.

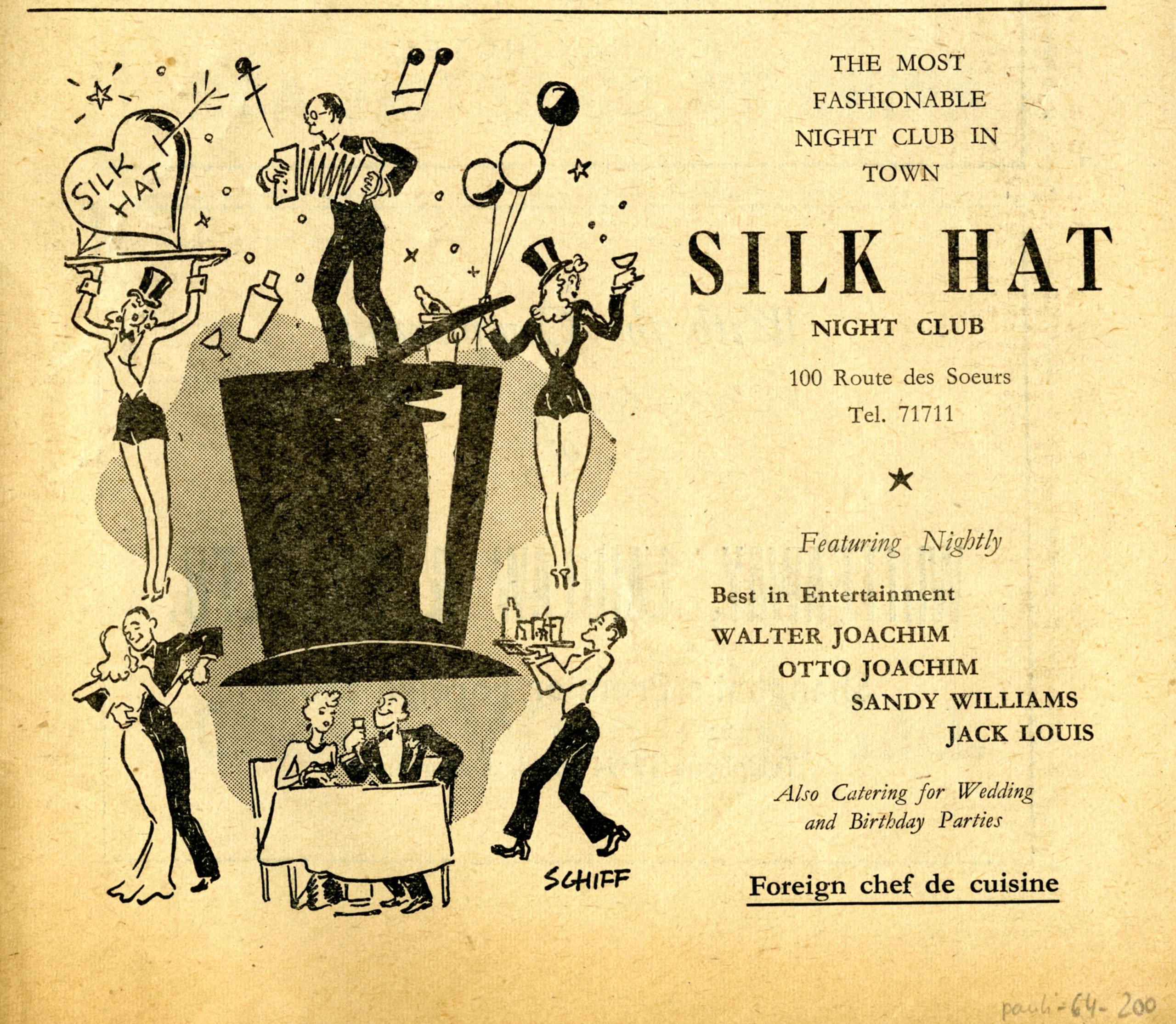

In his business showrooms, Paulick organized shows of historic and contemporary European prints including artists such as Käthe Kollwitz or Lesser Ury; he also featured group exhibitions showcasing German and Austrian Jewish professional and autodidact artists in order to promote their art in Shanghai. At the time, Schiff was already a renowned painter, cartoonist and graphic designer who ran his own art school and published his cartoons in major Shanghai-based newspapers, such as the North China Daily News (NCDN). Together with the journalist and photographer Ellen Thorbecke (1902–1973), he published several books about Chinese cities, published partly by the Shanghai branch of Kelly &Walsh and the NCDN. Thorbecke travelled to Shanghai in 1931 and could not return to Berlin due to her Jewish background, similar to Schiff who arrived from Vienna one year earlier. Favoured by the foreign elite and the amusement industry, Schiff created graphics and decorations for fashionable nightclubs, bars and restaurants in the city, such as the Pelican Nightclub. Today, there are almost no traces of this formerly community and of the original hotel interiors only fragments remain.

Friedrich Schiff, Advertisement Silk Hat, pauli–64–200 (© Architektur Museum der TU München).

03Waibaidu Bridge (former Garden Bridge) and Broadway Mansions/ 20 North Suzhou Road, Hongkou District

Leaving the Bund behind, the route leads across Waibaidu Bridge, the former Garden Bridge over Suzhou River where it meets Huangpu River. This is where Dreifuß’s walk starts. North of the former Garden Bridge sits the Broadway Mansions, which Dreifuß describes as the only skyscraper that could be seen when he arrived in Shanghai in 1939. His first impressions of the city might be shaped by the circumstances of his arrival and the shock of a reality beyond any previous experience and expectations, or simply by the dense fog covering other high rise and large-scale buildings such as the Skyline of the Bund, since his landing pier was probably located north to the Bund at the Wayside Wharf. By 1932 Shanghai had become the fifth largest city in the world and witnessed a real estate boom with Sassoon as one of the main protagonists. It led to a flowering of luxurious multi-story office, apartment, hotel and leisure buildings accompanied by big scale and low-rise residential structures, called lilong or shikumen houses. The influx of millions of refugees from the lower Yangzi areas, which were wrecked by war and devastation, increased the urban population dramatically, overwhelmed the municipalities and fuelled the real estate market.

Picture postcard of the Soochow Creek looking towards the Mansions Building at The Bund, around 1930–1937 (© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Ralph Harpuder).

Next to the Broadway Mansions the Garden Bridge leads over the Suzhou River.

The Broadway Mansions were completed in 1934; they were designed by the Palmer and Turner architect Bright Fraser (1894–1974) and built by Sassoon’s Shanghai Land Investment Company. Conceived as luxurious apartment buildings or residential hotels, the mansions included various leisure facilities and office spaces. It is still a prominent landmark today. The troubled and eventful history of the building, however, also reflects on the city as a war zone, a place of refuge and a place to flee from at the same time. Situated in southern Hongkou, next to Waibaidu (formerly Garden) Bridge, close to the Bund and an urban zone which was called Little Tokyo at that time, it became a social and commercial space for the Japanese living and working in Shanghai. Crossing the Garden Bridge became a humiliating affaire for the Chinese who had bow in front of the military guards watching the transfer from one power sphere into the other. After 1937, the Broadway Mansions turned into a headquarter for the Japanese army and is remembered as a dreaded interrogation facility.

A Chinese resident bows to the Japanese patrol before crossing the Garden Bridge over Soochow Creek in Shanghai, around 1937–1945 (© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Ralph Harpuder).

04Capitol Building/ Suzhou Road, corner Huqiu Road, Huangpu

Before we proceed northeast along the Huangpu River with Dreifuß, our route leads us back over the Suzhou River in a five-minute detour. Following North and South Suzhou Road, the next stop is the Capitol Building at the corner of South Suzhou Road and Huqiu Road. The cities nightlife offered good business for migrated or exiled architects and artist – from large commissions to smaller service jobs. In the exile press can be found some job offers for good looking barmaids.

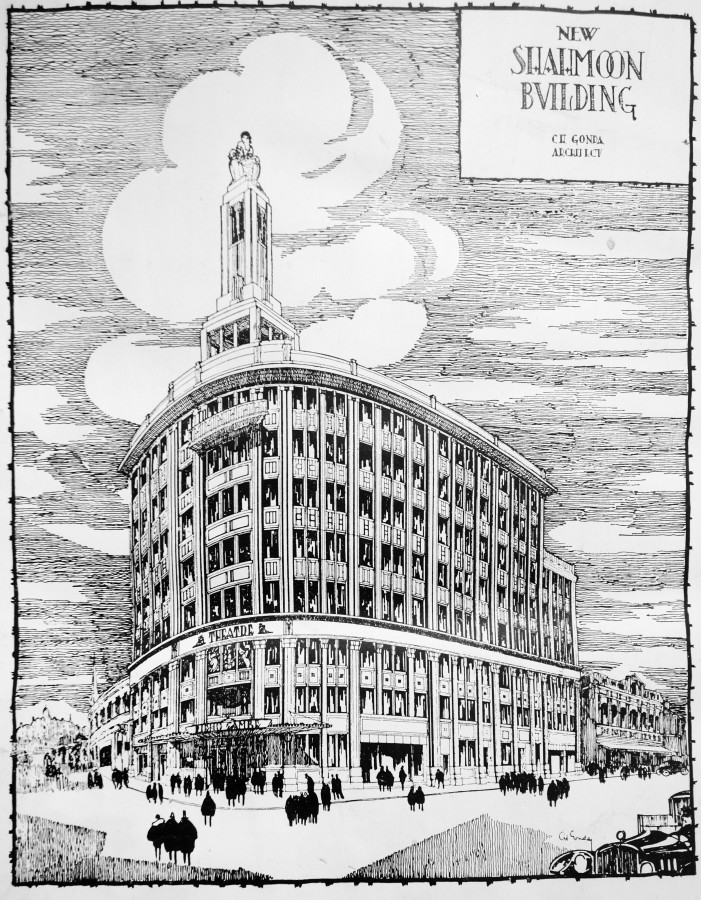

The Capitol Building was financed by Messrs SE Shamoon & Co. and built by C. H. Gonda (1889–1966) in 1927. Gonda, born as Karoly Goldstein in the disappearing Austro-Hungarian Empire, was educated in Vienna, Paris and London. He served during WWI, was captured in a Russian prisoner’s war camp and arrived in Shanghai in 1920.

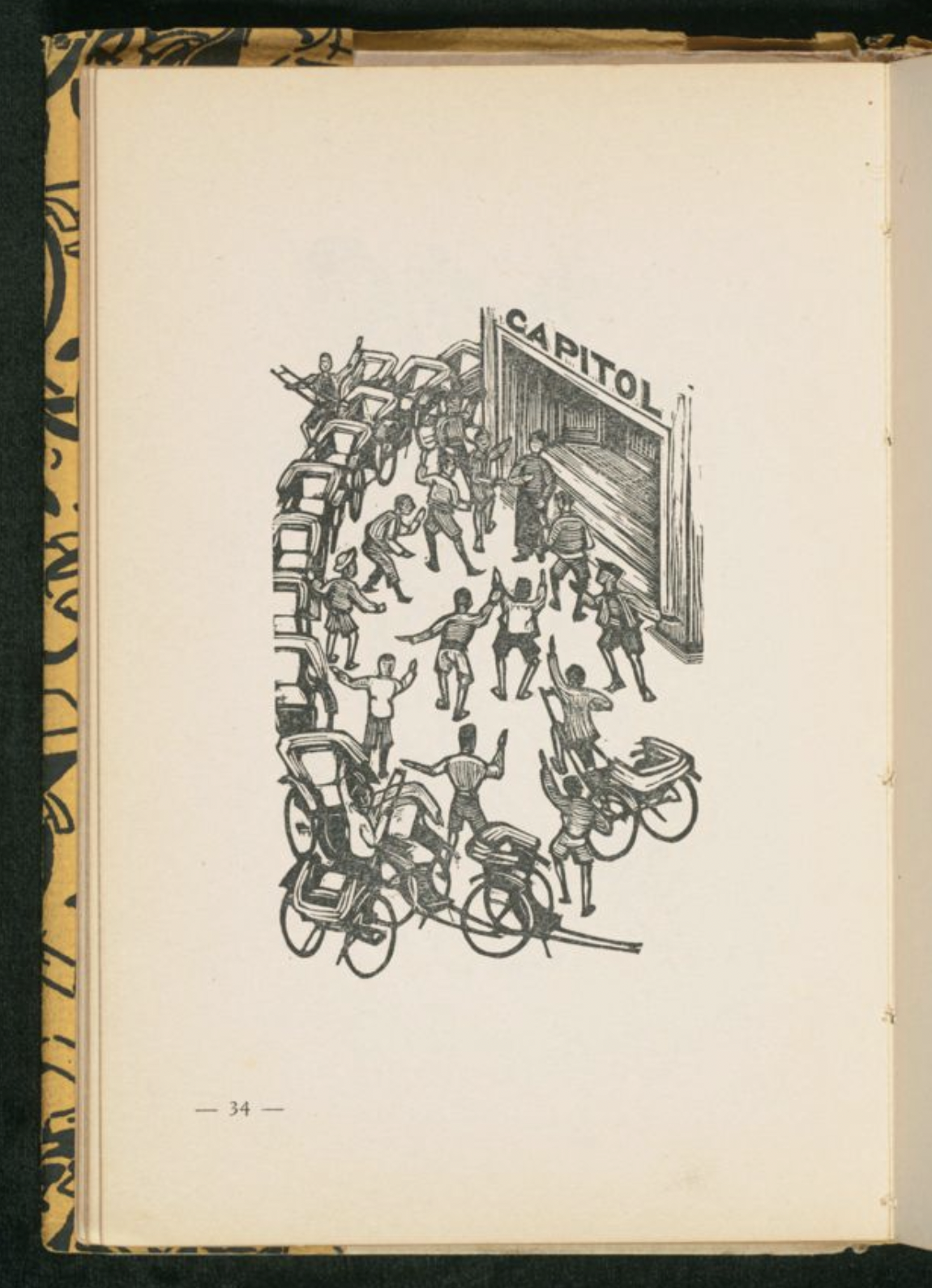

The Capitol Cinema, located on the ground floor of the eight-story building, was ran by Paramount Pictures and was one of the largest and most modern (1000 seats, air conditioned) movie theatres at the time. Next to Hollywood’s office branches, the building also housed Gonda’s own architectural firm. In addition to theatres and larger buildings, Gonda also executed modern interior designs, for example for the Restaurant Valencia which was run by Russian émigrés and located at Szechuan Road (today Sichuan Road) in Hongkou and which no longer exists today. From a newspaper article announcing the opening of the restaurant, we learn that Gonda had worked out a “design entirely along the modern line” (North China Daily News, “Last Idea of Gonda”), while the Viennese artist Schiff added some art panels to it. Equipped with an advanced ventilation system, “many heavy ‘morning after’ heads may be avoided, due to the foresight and skill of the architect.” (ibid.)

Malcom Rosholt, Sandbags outside Capitol Theatre (Cinema), Shanghai, 1937 (© 2012 Mei-Fei Elrick and Tess Johnston, University of Bristol, www.hpcbristol.net).

Sax-Darnous. "Houang Pao Tch'ô." Revue National Chinoise, vol. 22, no. 156, 1946, pp. 56–57. This article was published on the occasion of Bloch's book Rickshaw.

C.H. Gonda, New Shamoon Building, drawing.

It housed the Capitol Theatre.

Julius Wentcher, Bund, China Het Rijk Van Het Midden. Koninklijeke Drukkerijen G. Kolff & Co., Batavia–C., 1933.

David Ludwig Bloch, Rickshaw, book of woodcuts, Capitol, cover, ink on paper, 20 cm x 14 cm, Taiping Yinshua Gongsi, Shanghai, 1945, p. 34, David Ludwig Bloch Collection (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York).

05Suzhou River/

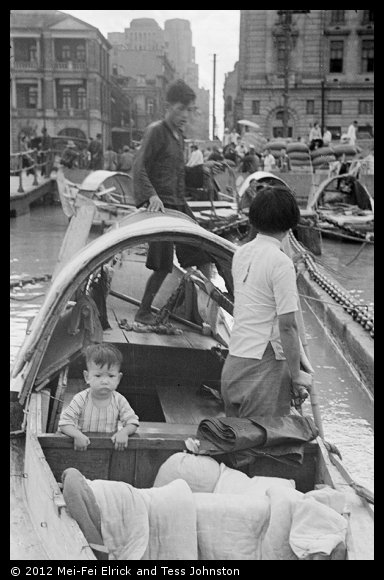

The next building on our route can be reached by a walk along the riverbank promenades of the Suzhou River. Today there are at least four bridges until you finally arrive at the Embankment Building and you can freely cross the river a few times to discover the neighbouring districts. Naturally, the river played a crucial role in Shanghai’s industrial and urban development and in its history of migration and exile. The geopolitical value of the river, flowing through the city centre from the very west into the Huangpu River, is related to its economic and logistic function which in turn shapes the architectural and, vice versa, the social composition of its neighbouring districts. Parts of the remaining lilong and shikumen or warehouses architecture are still visible today. Beyond this, the river functioned as a border and powerful barrier dividing the urban space into different national territories with wide-reaching consequences to Shanghai’s inhabitants. The bridges became neuralgic zones staging dramatic events during the war. Before the different sections merged into the International Settlement (1863), the river had separated British and American territories. With the Japanese Invasion during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), it acted as a demarcation line initially organizing the urban space into war zones and more or less safe zones. Controlled by the authorities, the bridges over the Suzhou Creek facilitated and regulated the passage from one sphere into the other. However, Suzhou River with its many boats and busy traffic was a popular motif for artists and photographers. Also, Dreifuß described a river scenery, the tangle of the little boats floating under the bridge in the evening, evocatively embellished by the howl of a dog sitting on the bug of a passing barge.

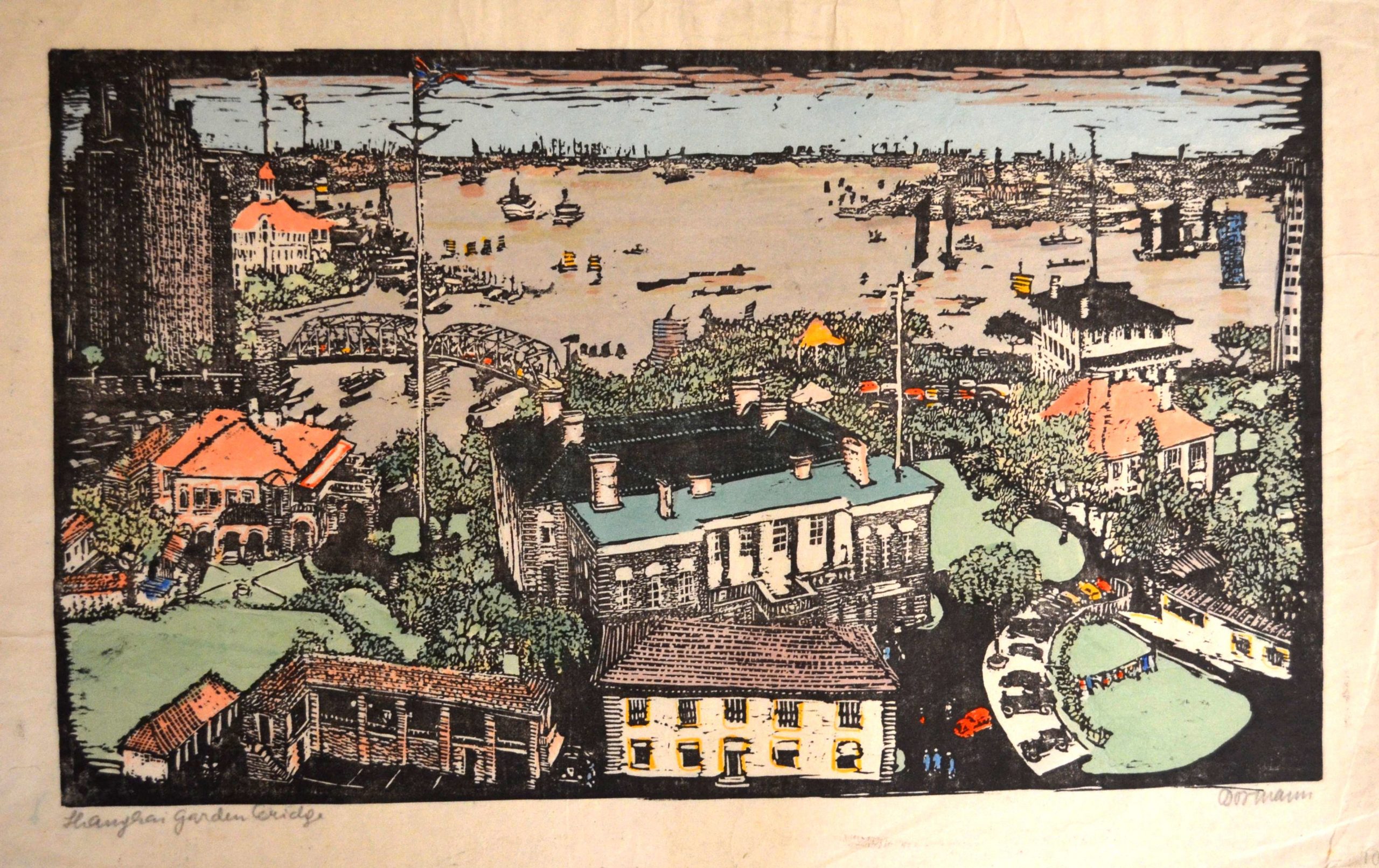

Emma Bormann, Garden Bridge, 1940s, woodcut or linocut (© private collection).

The print shows a distant perspective of the river mouth of the Suzhou River, Gardenbridge and the Broadway Mansions. The view sweeps over the city, alongside the Huangpu River and to the horizon where the sea begins.

Malcom Rosholt, Family in Sampan, off The Bund, Shanghai, 1937 (© 2012 Mei-Fei Elrick and Tess Johnston, University of Bristol, www.hpcbristol.net).

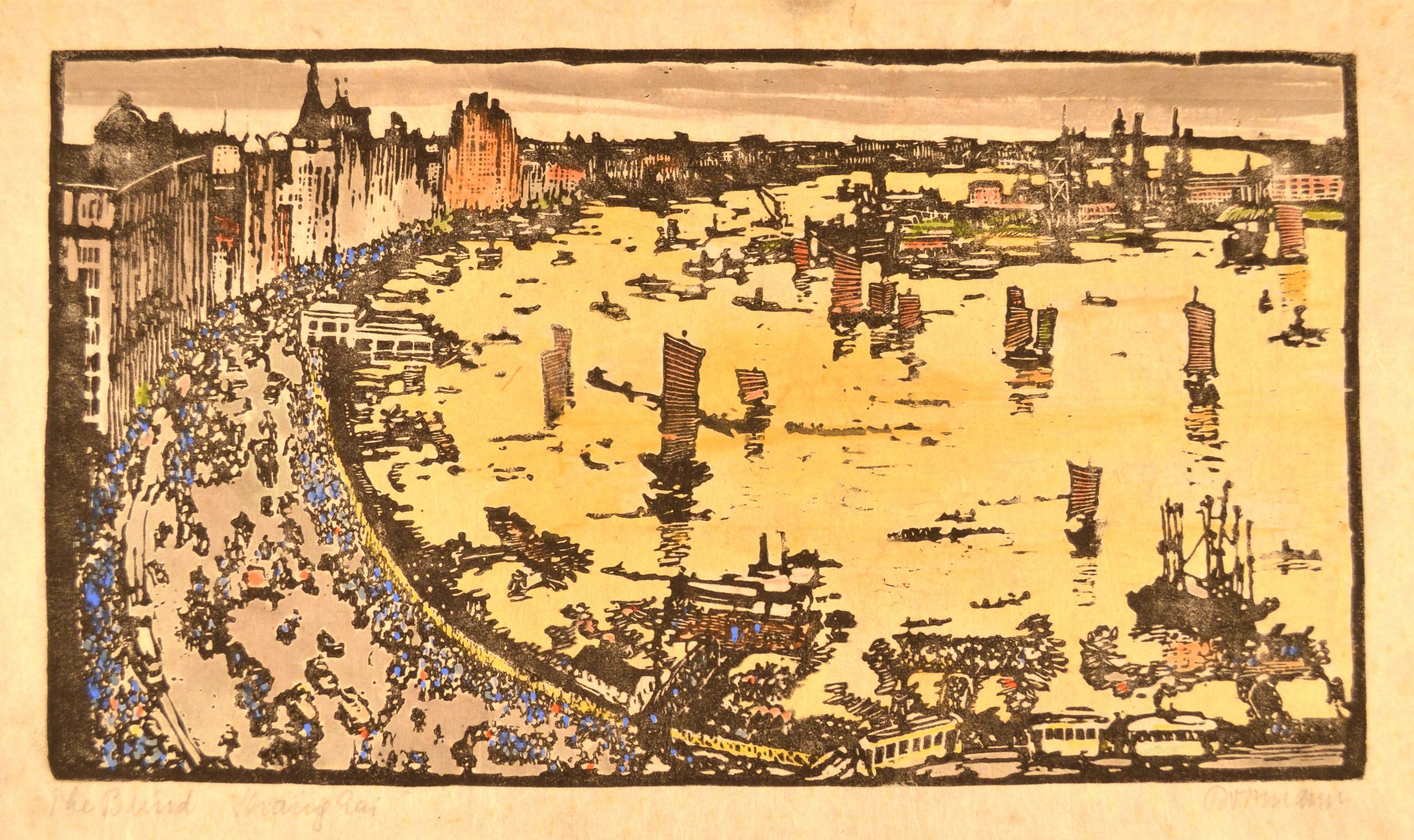

Julius Wentcher, Haven van Shanghai, China Het Rijk Van Het Midden. Koninklijeke Drukkerijen G. Kolff & Co., Batavia–C., 1933, p. 35. The drawings of Julius Wentcher (1881–1961) are reminiscent of postcards views, as they, too, employ distant and high vantage points. The painter Julius Wentcher and the sculptor Tina Haim-Wentcher (1887–1974, Melbourne) travelled to Indonesia in the beginning of the 1930s.

Julius Wentcher, Soochow Creek, China Het Rijk Van Het Midden. Koninklijeke Drukkerijen G. Kolff & Co., Batavia–C., 1933, p. 35. Due to the political situation in NS Germany, the Wentchers did not return to Germany and travelled further in South East Asia and China. From 1940 to 1942, they were interned as “enemy aliens” in Australia where they stayed and received citizenship.

Chinese refugees streaming over Garden Bridge onto The Bund, Shanghai, August 1937 (© 2014 Historical Photographs of China, University of Bristol, www.hpcbristol.net).

Photograph taken from the Broadway Mansions.

06Former Embankment Building/ 400 North Suzhou Road, Hongkou

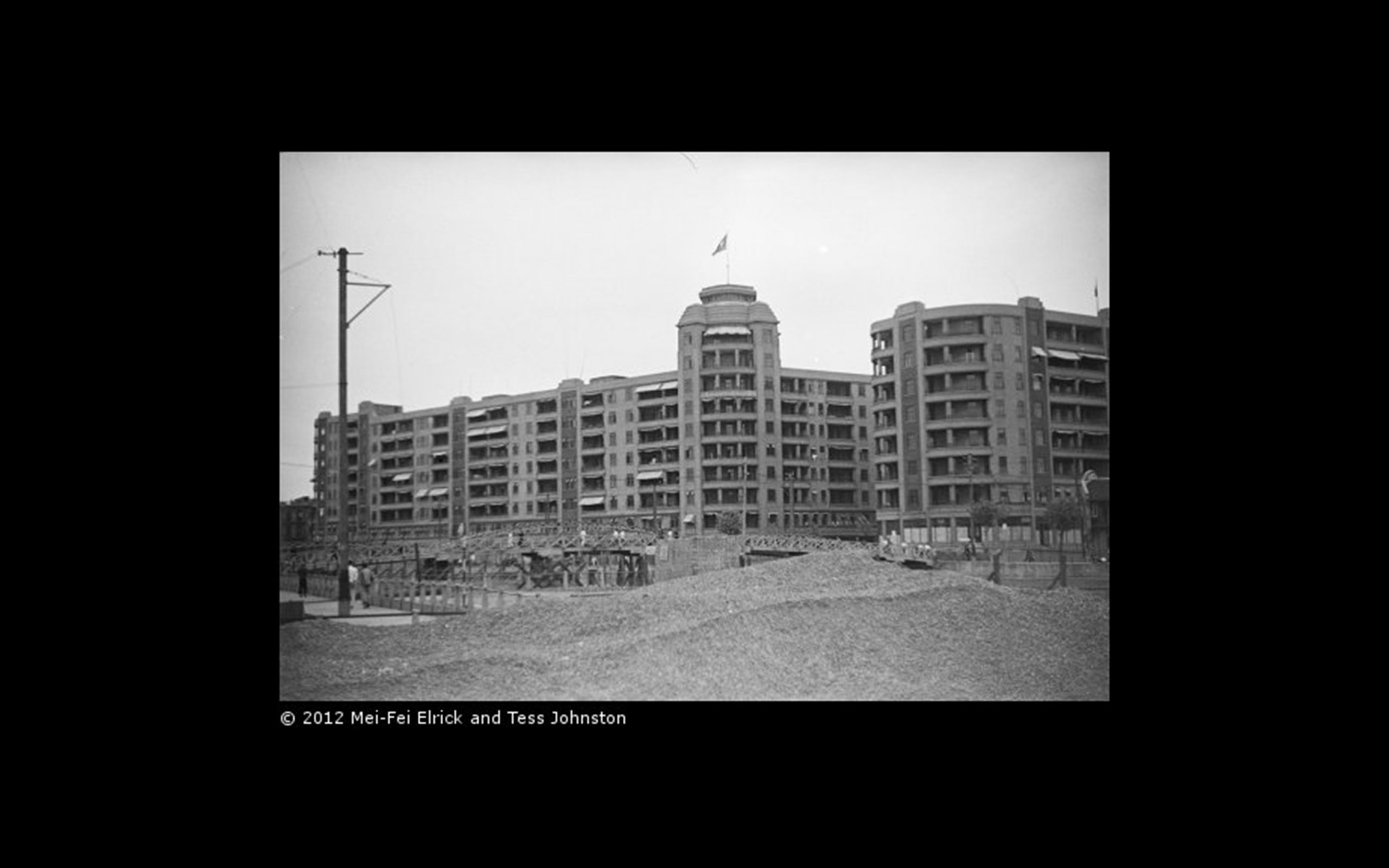

The large Embankment Building, located between Henan Road, North Suzhou Road and Jiangxi North Road, was built in 1932, again by Sassoon and Palmer and Turner. It was one of the largest apartment buildings in Shanghai at the time. Expanding in serpentine arcs over eight floors and housing 194 apartments equipped with central heating, lifts and a swimming pool, it was designed for wealthier clients, for example the employees of Sassoon’s various enterprises.

In 1938 Sassoon opened the building to Jewish refugees arriving from Nazi Germany and Austria. At what was then one of several reception centres, they received shelter, food and clothes.

Malcom Rosholt, Embankment House, Shanghai, around 1937 (© 2012 Mei-Fei Elrick and Tess Johnston, courtesy University of Bristol, www.hpcbristol.net).

Embankment Building, 2019 (© Mareike Hetschold).

Embankment Building, staircase, 2019 (© Mareike Hetschold).

07Union Brewery/ 130 Yichang Road, Putuo

The Union Brewery was a nine-story house owned by Sassoon and it was designed by László Ede Hugyecz, also known as L. E. Hudec (1893–1958). Completed in 1934, the brewery started production in 1936. With a yearly production of five million bottles of beer it was the largest brewery in China. Like Gonda, Hudec was born in the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, served during WWI on the Russian front and had been imprisoned in Eastern Siberia. Via Harbin he arrived in Shanghai in 1918. There, he started to work for the architectural firm R. A. Curry before he opened his own business in 1925 at the Bund. Today, the few preserved structures of the Union Brewery are part of the Meijing Park. In 2002, due to the ongoing Suzhou Creek Rehabilitation Project launched in 1998, the building complex was nearly completely demolished for public green. But the architects’ modern approach is still visible: the original structures followed clear lines with unobtrusive art deco ornaments. Once, the complex had consisted of a brewery station, a filling area, a warehouse, a powerhouse and offices – all functionally grouped together in order to serve the production process and demands of the nightlife.

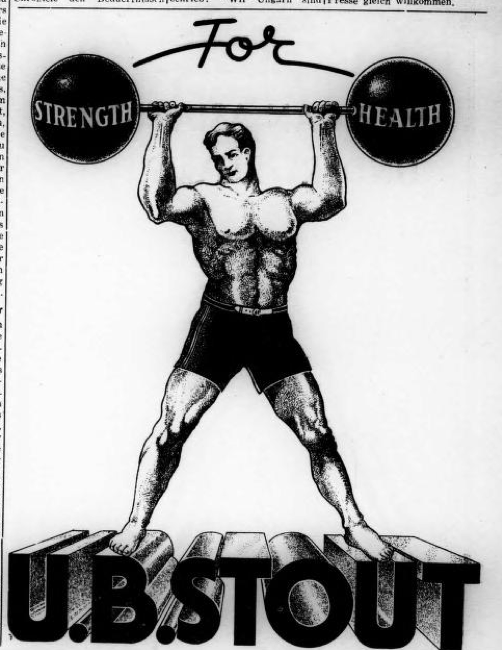

Advertisement, UB Bier, Shanghai Woche, 14 April 1939, p. 3.

Advertisement, UB Beer, Shanghai Woche, 16 June 1939, p. 3.

Advertisement, UB Stout, Two Years Shanghai Chronicle, 11 May 1941, p. IX.

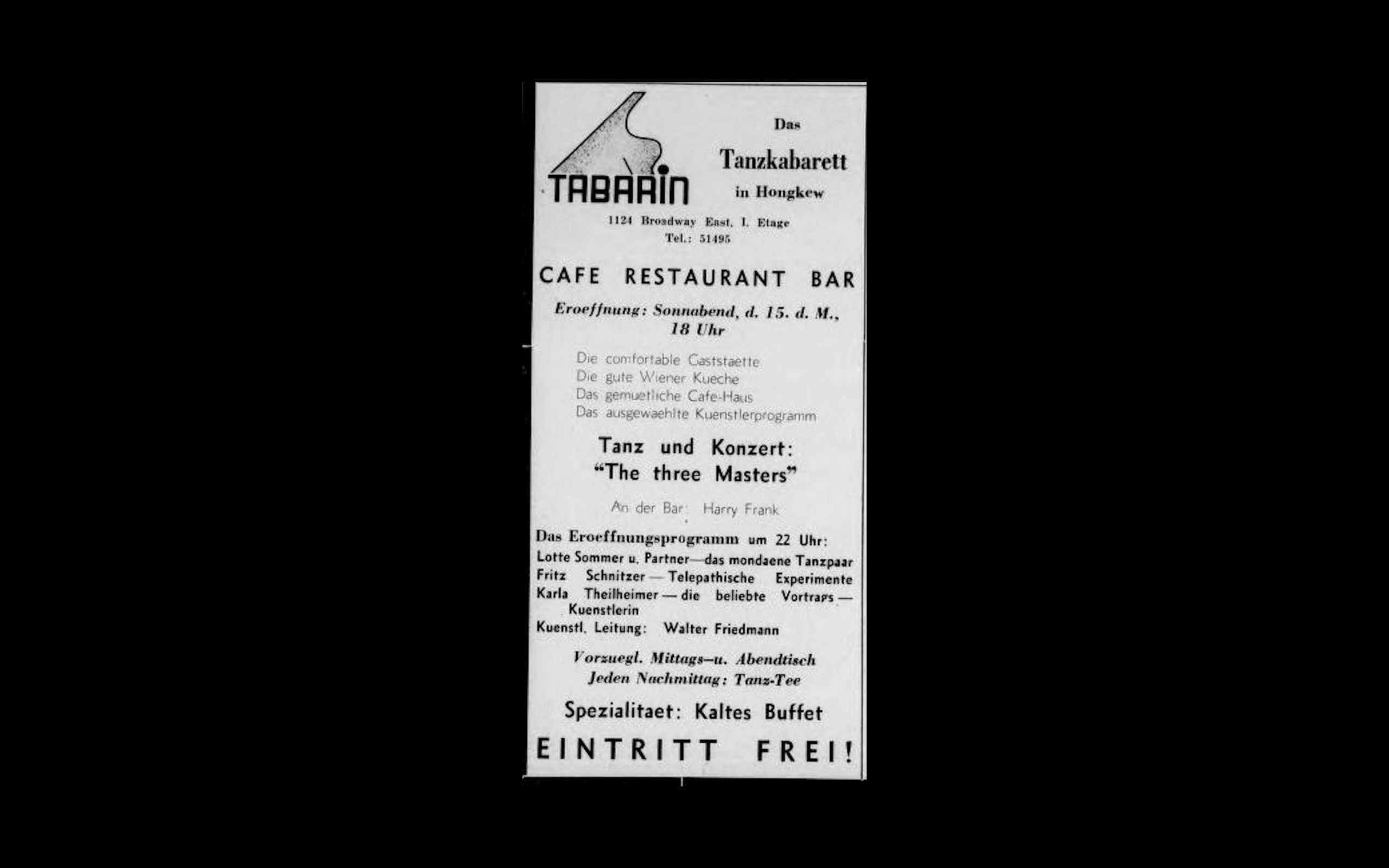

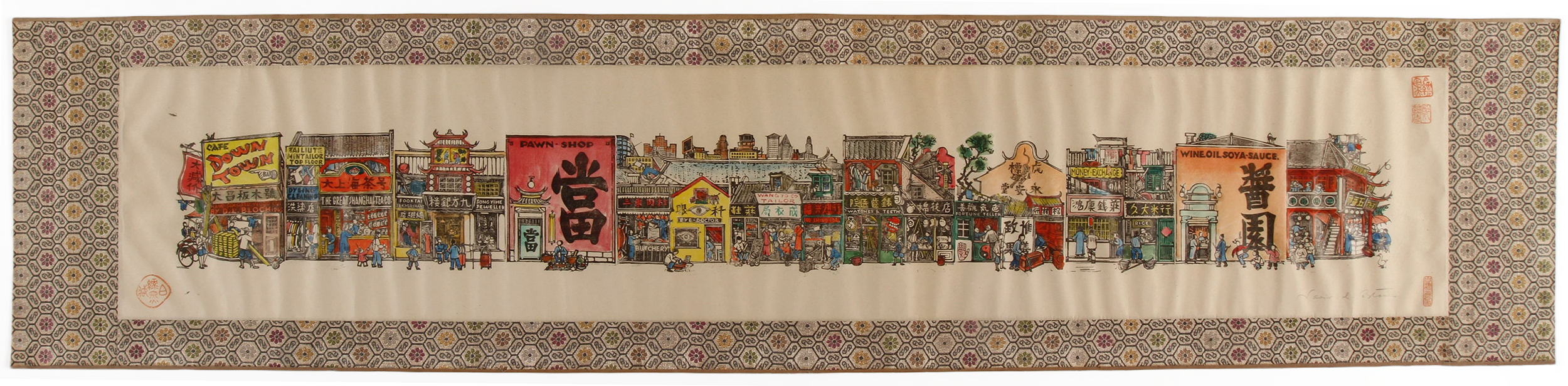

08Dongdaming Lu/ (former Broadway East)

After the little excursion along the Suzhou River, the route leads back to the Huangpu River and to Dreifuß’s story. It guides us to Dongdaming Road, formerly East Broadway, and then to Gongping Road, formerly known as Kungping Road.

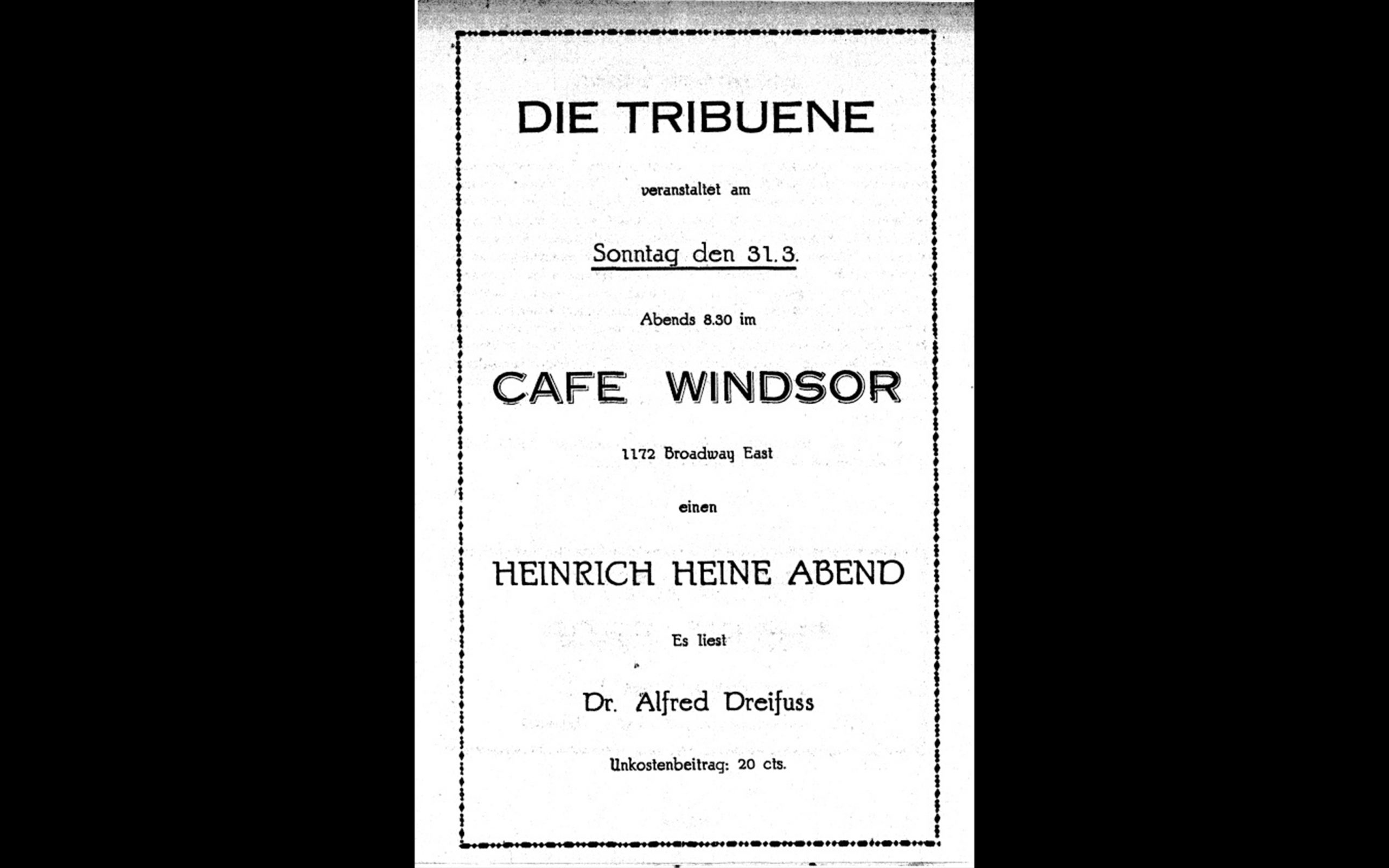

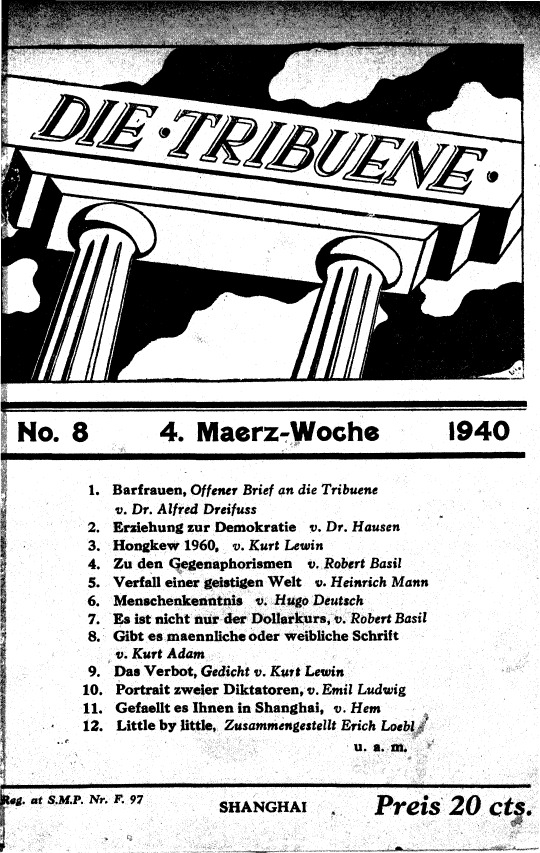

Today, little reminds of the small lanes and the street Dreifuß described as Kungping Road in his text. The shops, bars, cafés and restaurants situated at East Broadway which were mostly ran by émigrés are long gone. Among these establishments counted the Tabarin decorated with fashionable wall paintings, Café Imperial with interior design by Paulick, or Café Windsor where Die Tribüne organized literary events such as Heinrich Heine evenings with Dreifuß as a performer. Die Tribüne was a small German literary weekly edited by Heinz Petzall and Kurt Lewin; it was published with Centurion Printing Co. from February to May 1940 before it had to be discontinued due to Japanese censorship.

Advertisement, Café Windsor, Die Tribüne, no. 8, 1940, p. 281.

Imperial Bar, interior, 1939–1948 (© Werner von Boltenstern Shanghai Photograph and Negative Collection. Department of Archives and Special Collections, William H. Hannon Library, Loyola Marymount University, https://digitalcollections.lmu.edu/collections/werner-von-boltenstern-shanghai-photograph-and-negative-collection).

Tabarin, interior, 1939 (© Werner von Boltenstern Shanghai, Photograph and Negative Collection. Department of Archives and Special Collections, William H. Hannon Library, Loyola, Marymount University, https://digitalcollections.lmu.edu/collections/werner-von-boltenstern-shanghai-photograph-and-negative-collection).

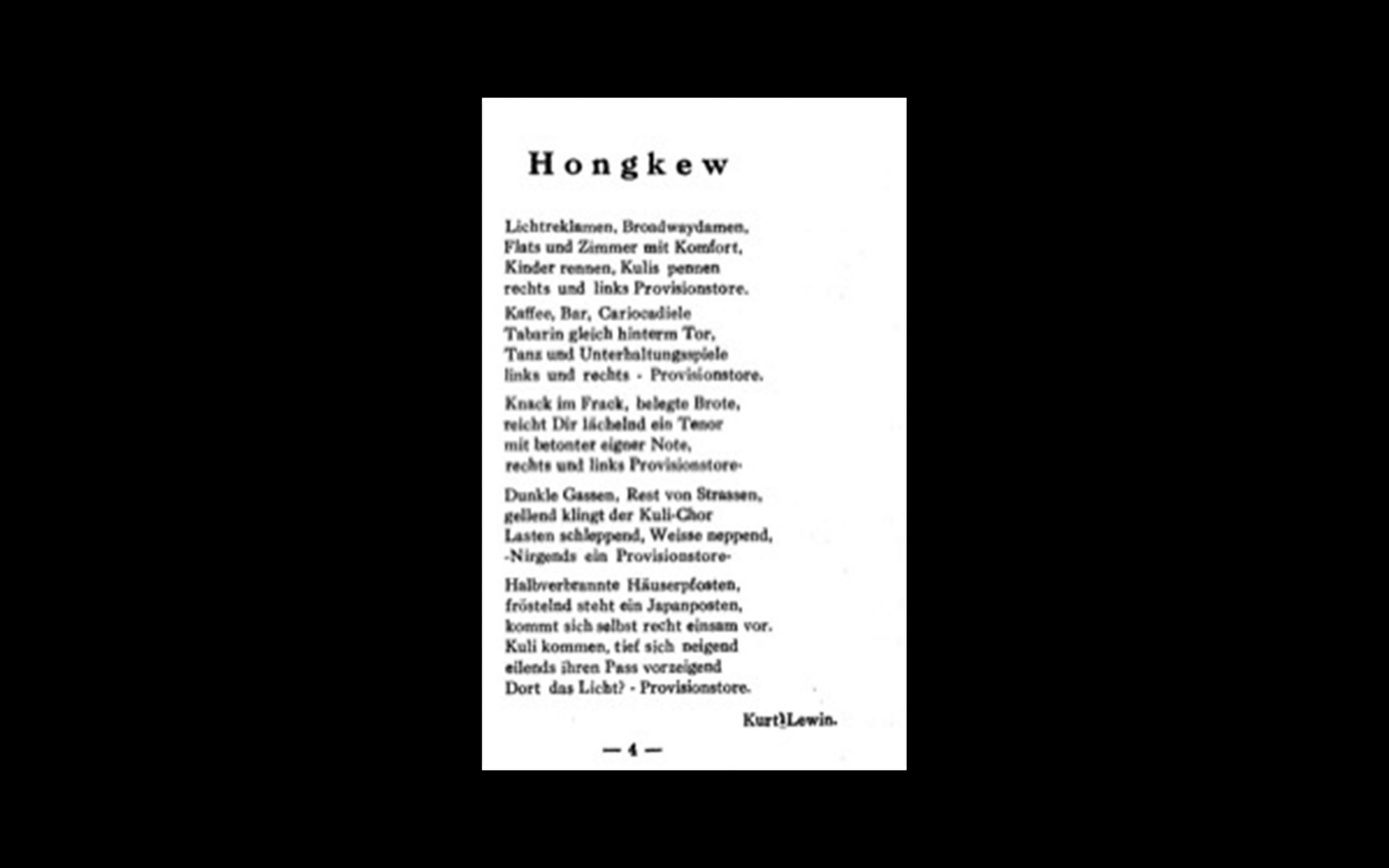

Die Tribüne featured poetry, articles, short stories, letters, critiques and commentaries. The cover lettering was made by Hans Less. Lewin’s texts for Die Tribüne related his bitter exile situation with snappy humour. In his short text Honkew 1960… (Lewin 1940, 249f.), for example, he imagined the future life of the exile community around the Broadway in Shanghai. Here is a rough sketch of his vision: crowds of the most elegant people flow out of the feudal Honkew Theatre built on a spacious square at the corner of Baikal Road (now Huimin Road) and East Broadway (now Dongdaming Road); they are celebrating the new year 1960.

Doors of elegantly streamlined cars are hastily opened by pageboys, a stream of cars surges up Broadway where luxurious restaurants await the festive crowds. Past suffering is mere memory, the Heim at Ward Road in Hongkou an odd museum.

This exaggerated fantasy of future luxury, of healthcare and a functioning food supply system evokes contradiction and reveals the depressing living conditions in the ghetto. Aside from the numerous businesses led by emigrants, the Broadway, close proximity to the marine landing stages, was by then also known for its industrial and rougher urban appearance, accompanied by all kinds of bars and cafés. The ‘moral integrity’ of European women working in its bars, for example, caused contentious public debates among the male emigrant community.

Die Tribüne, no. 8, 1940, cover.

The cover lettering was made by Hans Less.

Medizinische Wochenschau (Medical Weekly Review), Shanghai Jewish Chronicle, 8 July 1941, p. 4.

The cover lettering was made by Hans Less.

09Hongkou (former Designated Area)/ Gongping Road (former Kungping Road)

In relation to the number of its inhabitants, the formerly designated area (the so-called Shanghai Ghetto) took up little space. The ‘Heime’ [asylums] were overcrowded, as were the private apartments. The hygienic and sanitary situation was precarious and caused epidemic outbreaks of diseases with high fatality rates, further fuelled by insufficient nutrition. The living conditions deteriorated continuously with the ongoing war. Already facing harsh economic conditions, for many the forced movement meant the loss of their previous income opportunities, as well as their professional and social networks. Due to the already scarce living space, it was extremely difficult and expensive to find an apartment or room, particularly since several of the buildings inside the designated area and along Kungping Road were damaged by bombs and had to be rebuild by the emigrant community. The pride in the emigrant community’s achievements can be found not only in Dreifuß’s account, but also in many articles in the exile press.

Quisisana hot dog stand, 1939 –1948 (© Werner von Boltenstern Shanghai, Photograph and Negative Collection. Department of Archives and Special Collections, William H. Hannon Library, Loyola Marymount University, https://digitalcollections.lmu.edu/collections/werner-von-boltenstern-shanghai-photograph-and-negative-collection).

Quisisana is the evolution of Knack im Frack, a small sausage and drink stall with street vending. Despite the previously held belief that Europeans would not eat on the street, it was successfully operated by Oscar Steiner and Erwin Sachsenhaus. Previously, the footstall stood in front of the Tabarin and attracted diplomats as well as rickshaw drivers, and Alfred Dreifuß.

Kurt Levin, Hongkew, Die Tribüne, vol. 2, 1940, p. 4.

The Knack im Frack sausages and the Tabarin also received an artistic tribute from Kurt Lewin in his poem Hongkew. Other sausage shops were Oellendorf on Chusan Road or the Wuerstel Tenor. The latter also finds also its echo in Lewin's poem. The initially rather upbeat and comic rhymes turn into sombre-sounding ones towards the end. Against the direction of Alfred Dreifuß’ Broadway Melody, the lines of Lewinʼs poem run south along Broadway, witnessing the bomb damages and altering urban zones and population ending at a Japanese checkpoint.

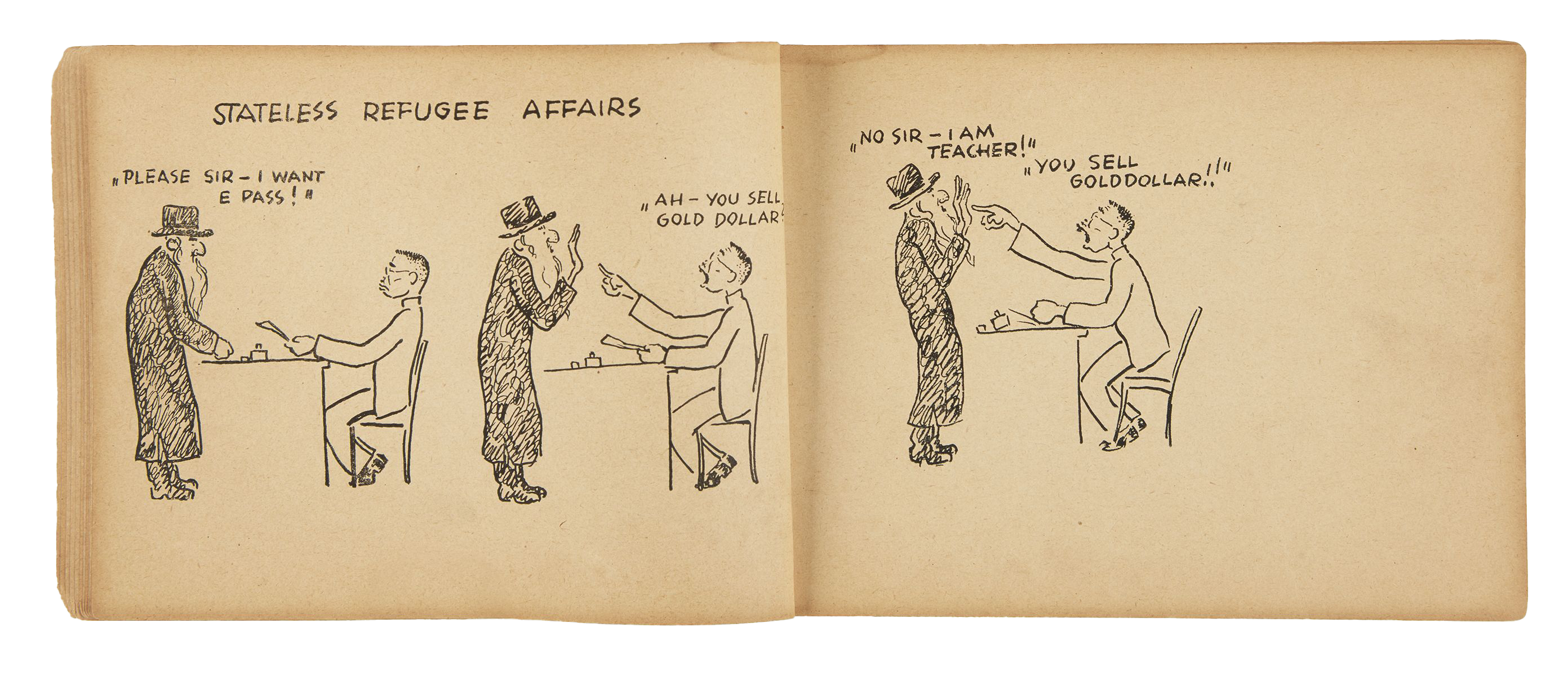

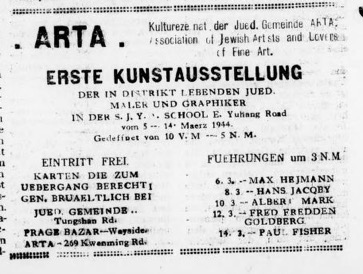

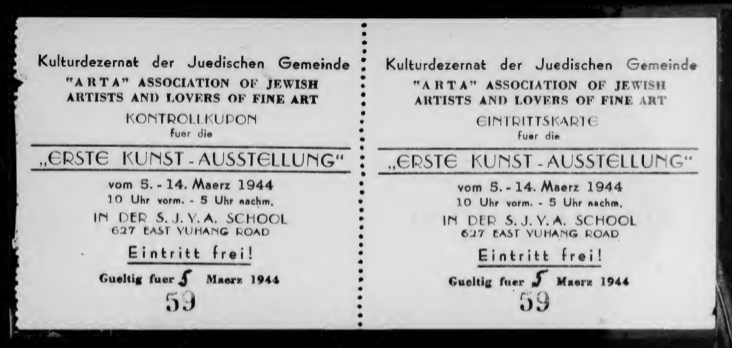

The ongoing inflation intensified the situation. Artistic supplies were hard to come by and jobs within the designated area rare. Some of the artists living in the district, including David Ludwig Bloch, Paul Fischer, Max Heimann, Fred Fredden Goldberg, Ernst Handl, Hans Jacoby and Alfred Mark, formed an association, the ARTA/Association of Jewish Artists and Lovers of Fine Arts, in order to promote their work. Between 1943 and 1945 they were able to hold at least two exhibitions. Among (not many) others, Alfred Dreifuß documented these exhibitions, for example by writing about them in the Shanghai Jewish Chronicle or Die Tribüne.

Besides In addition to the (insufficient) financial assistance that could be obtained from the aid organizations, artists and writers were able to keep their head over water by designing advertisements or artistic decorations for cafés, restaurants, bars and shops, by taking on jobs in the print, theatre and performance scene, or by teaching – meanwhile, Kungping Road transformed into a sort of market street where emigrants sold their belongings on the sidewalks when things went worse.

Advertisement, ARTA Erste Kunstausstellung (ARTA First Exhibition), Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt, 4 March 1944, vol. 5, no. 9, p. 4.

The entrance was free of charge. The entrance ticket authorized the residents of the designated area to leave in order to get to the exhibition venue at the S.Y.Y.A. School at East Yuhuang Road, which was only a short distance away.

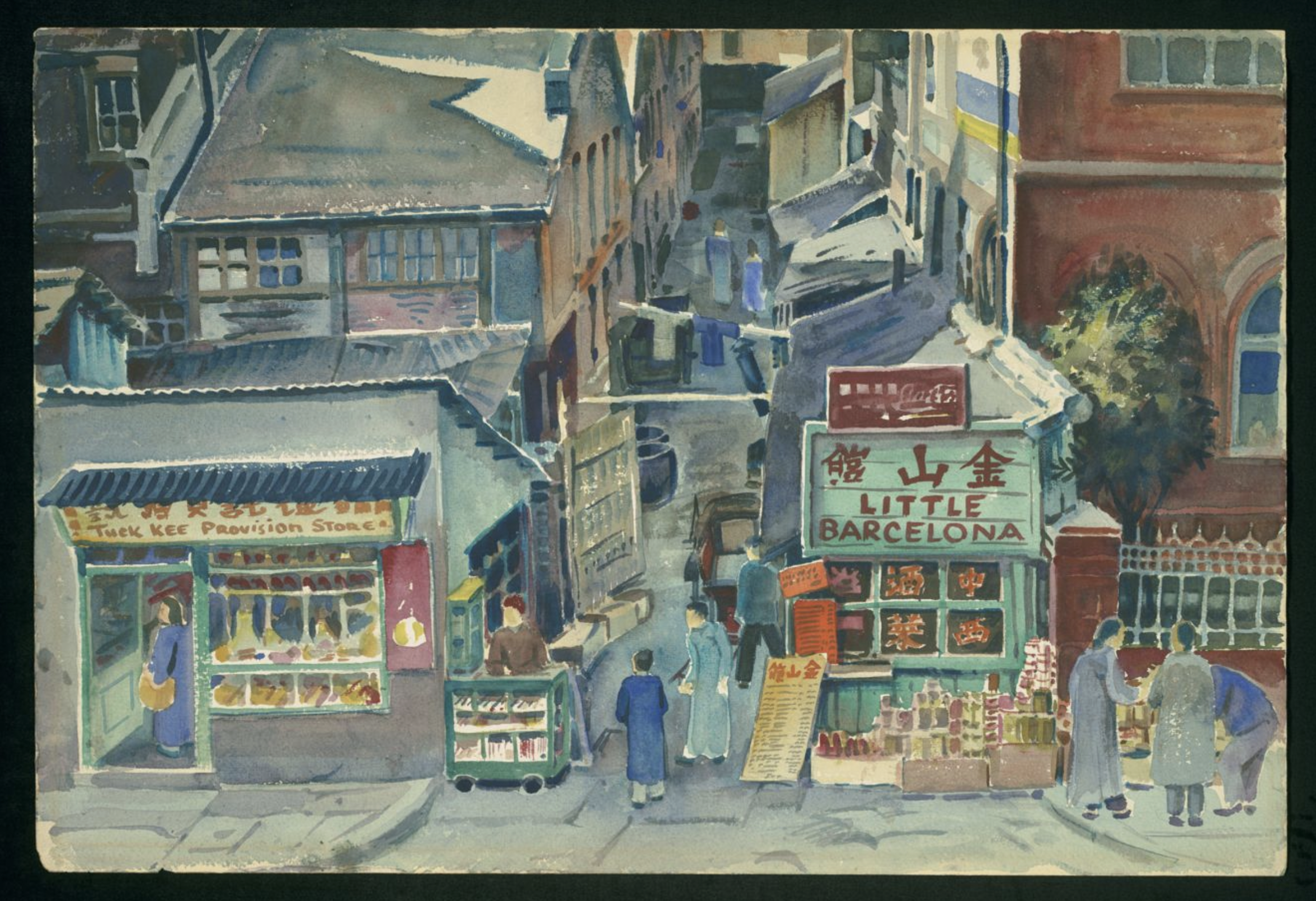

David Ludwig Bloch, Shanghai, Street Scene, watercolor on paper, 39 x 57 cm, 1949, Shanghai, David Ludwig Bloch Collection (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York).

Statistik der von der Proklamation betroffene Emigranten-Geschaefte.“ Shanghai Jewish Chronicle, 28 May 1943, p. 3. The title reads “Statistics of the emigrant businesses affected by the Proclamation”.

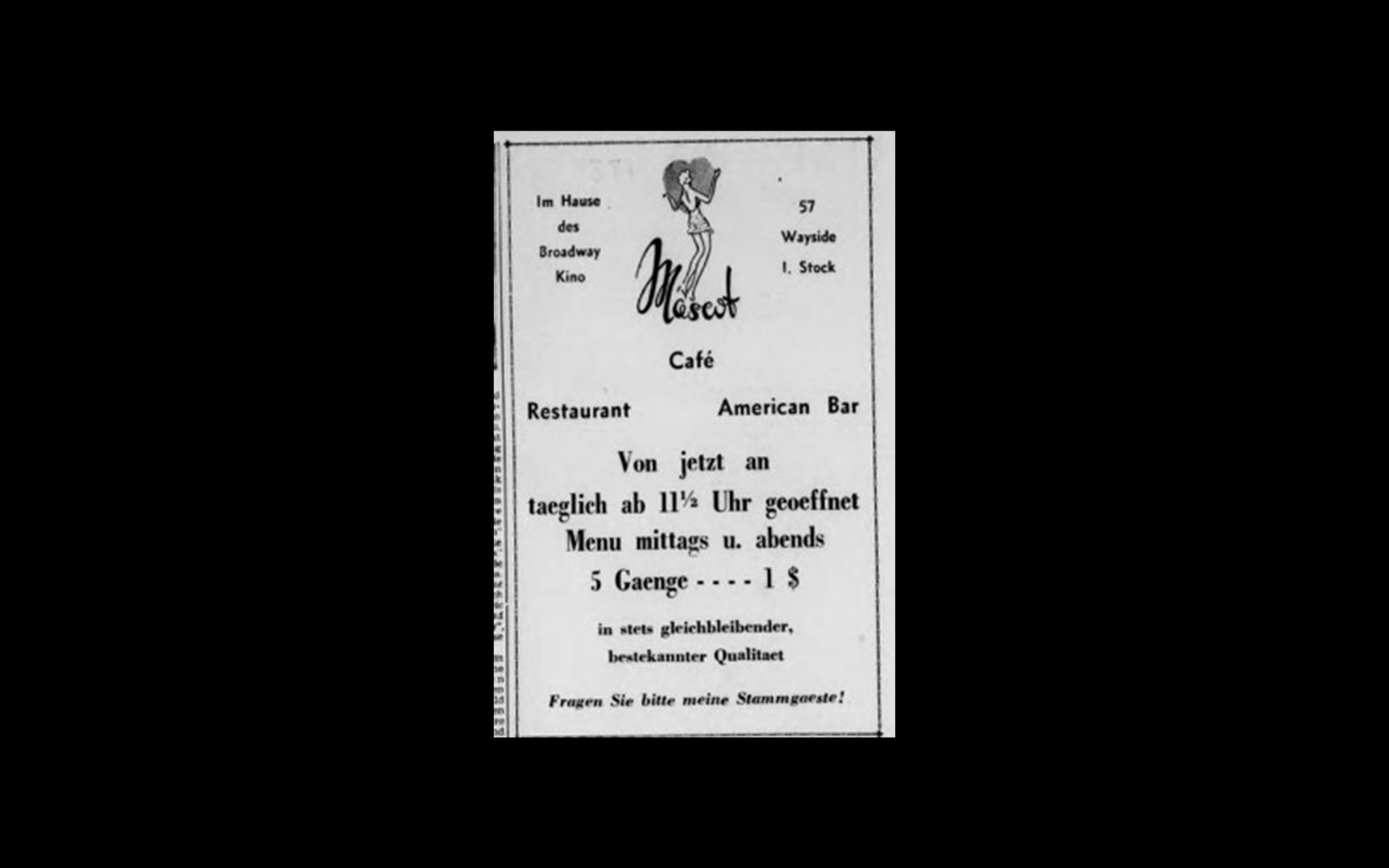

10Former Broadway Cinema and Mascot Roof garden/ Huashan Road, (former 57 Wayside Road), former Café Barcelona, Zhoushan Road (former 21 Chusan Road), Hongkou

When entering the heart of ‘Little Vienna’ in Hongkou, Dreifuß describes cinemas, theatres and outdoor cafés or restaurants – among them most probably the Broadway Cinema. Today, the Art Deco building that housed it is left vacant.

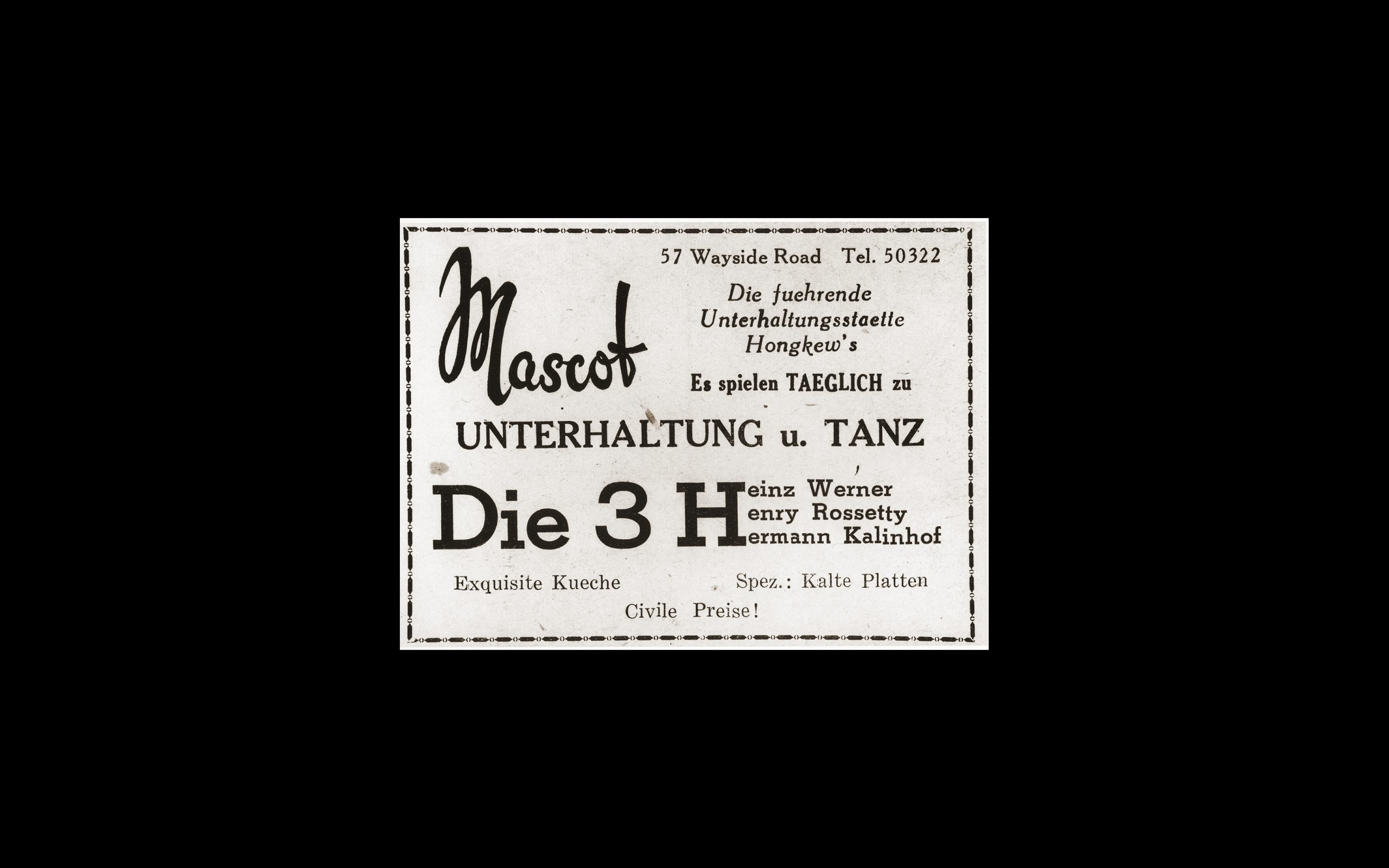

Broadway Cinema was a multifunctional social and cultural space for the emigrant community. Besides being a cinema, it put on theatre performances, religious services and housed a roof-top garden restaurant. The roof-top garden restaurant’s name was Mascot. It opened in May 1941 and would employ up to 30 émigrés. Soon it became a popular venue among emigrants, especially in the evenings when the open space on top of the building afforded some relief from Shanghai’s humid and hot climate and Hongkou’s cramped and badly climatized apartments and shelters. It was a space to read newspapers, to gather and chat and to enjoy the music performances in the evening. Rooftop facilities, also on large scale buildings were a distinct modern feature of Shanghais urban architecture and programmatically applied by the German architect Rudolf Hamburger.

The building of the Broadway Cinema that housed the Mascot Roof Garden in 2019 (© Mareike Hetschold).

Advertisement for Mascot, a restaurant and club operated by German Jewish refugees on Wayside Road in Shanghai (© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Ralph Harpuder).

This is most probably the cinema were Alfred Dreifuß’ Broadway Melody ends.

Advertisement, Mascot Café, Shanghai Woche, 26 May 1939, p. 4.

Advertisement, Tabarin, Shanghai Woche, 14 July 1939, p. 2.

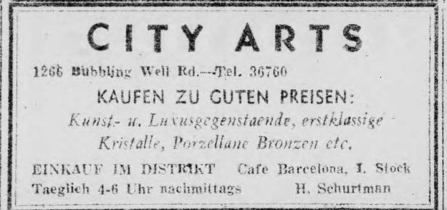

Another popular (outdoor) venue around the corner, especially among the ARTA artists, was the Café Barcelona on which was then located at 21 Chusan Road (now Zhoushan Lu). However, the original location of the building remains unclear. It was not only a place to gather but also to conduct business. H. Schurtmann who ran the gallery City & Arts at 1266 Bubbling Well Road, had a kind of branch at the first floor for the customers and artist living in the district. The busy street and café, however, were carefully depicted by the artists David Ludwig Bloch and Hans Jacoby.

While Bloch is one of the better-known artists who went into exile in Shanghai and lived in the designated area, much less is known is about the work of Jacoby.

Interned in Hoek van Holland in 1938, he could flee to Shanghai in 1940. The architect Richard Paulick employed Jacoby as a restorer and introduced him to art dealers, collectors and students.

David Ludwig Bloch, Chinese Street Scene (© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of David L. Bloch).

Advertisement, Café Barcelona, Shanghai Echo, 25 December 1946, p. 5.

Advertisement, City Arts H. Schurtmann, Shanghai Jewish Chronicle, 25 September 1943, p. 1.

ARTA, tickets, Hans Jacobi Collection, Box 1, Folder 5 (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York).

There were a few art dealers advertising the exile press, such as Hermann Schieberth who left behind a successful photographer carrier in Vienna advertised his new photo studio, specialized in artistic portraiture, and his show and art room Salon d’Art. He died in Shanghai in 1946. Other dealers, mostly but not only émigrés, were L. A. Benesi at 12 Rue du Consulat, Apt. 501 and later 38 Haimen Road, corner Muirhead Road, John Henschel at 30 Route Boissezon who acquired European oil painting, landscape and genre painting, Julius Goetzl and European Old & New Art at 20 Muirhead Road, formerly located in Berlin and Vienna, Edgar Hecht and Rembrandthaus who died in 1945 or Heinz Egon Heinemann and the Western Art Gallery. In October 1946 Heinemann held an exhibition in the Sun Department Store on Nanking Road showing “Berühmte Gemälde aus fünf Jahrhunderten in vollendeten Farbdrucken” (Famous paintings from five centuries in accomplished colour prints). Other émigré exhibitions at that time were by David Ludwig Bloch or Emma Bormann. Other venues were Everyman’s Library at the Broadway or The Lion Bookstore owned by Lisbeth und Bruno Loewenberg, Jacoby was interested in portraiture, and he worked both for free and on commission. In his memoir, he notes that his bestselling pieces were European landscapes in oil, which he painted for art dealers to secure an income until the total break-down of the art market. He took part in the two ARTA exhibitions in 1943 and tried to continue to work while facing health issues, malnutrition and bombing raids.

Besides Bloch and out of the scope of Alfred Dreifuß there was another exiled European woodcut artist working in Shanghai. Emma Bormann (1887–1974) arrived in China after her forced suspension from the Wiener Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt in 1939 in the same year. She followed her Jewish husband Eugen Milch (1889–1958), who worked with the Church Missionary Society as superintendent of the Puren Hospital in Pakhoi, today Beihai, in South China. In 1941, due to the Japanese Invasion, Bormann and her two daughters were forced to move to Shanghai. For this reason, her journey to China and Shanghai is different to her various previous travels. Not Jewish herself, she did not take part in the exhibitions of the Jewish exiled artists. Her works were promoted by Fritz Mass (1910–2005), the vicar of the German Evangelical Community in Shanghai. His support for Bormann and for non–Jewish inhabitants of the so–called Shanghai Ghetto brought him into conflict with the ‘NSDAP Ortsgruppe’ in Shanghai. In 1944, he was suspended from his service. Emma Bormann’s fraught connection to the network of Jewish artists as well as to remembrance processes at play within the European exile community in Shanghai might also help us address the enormous heterogeneity of artistic exile experience, which was deeply influenced by religion, gender, and differing sociocultural and political backgrounds.

That European artistic exile in Shanghai has not been as well researched and documented today might be rooted in its fragmented and scattered sources, its relatively short time span, its geographical context, or because most scholars tend to focus on artistic ‘elites’ or certain ‘modernist’ styles. Such an undertaking is certainly further complicated by the harsh and difficult exile conditions the European artists faced in Shanghai.

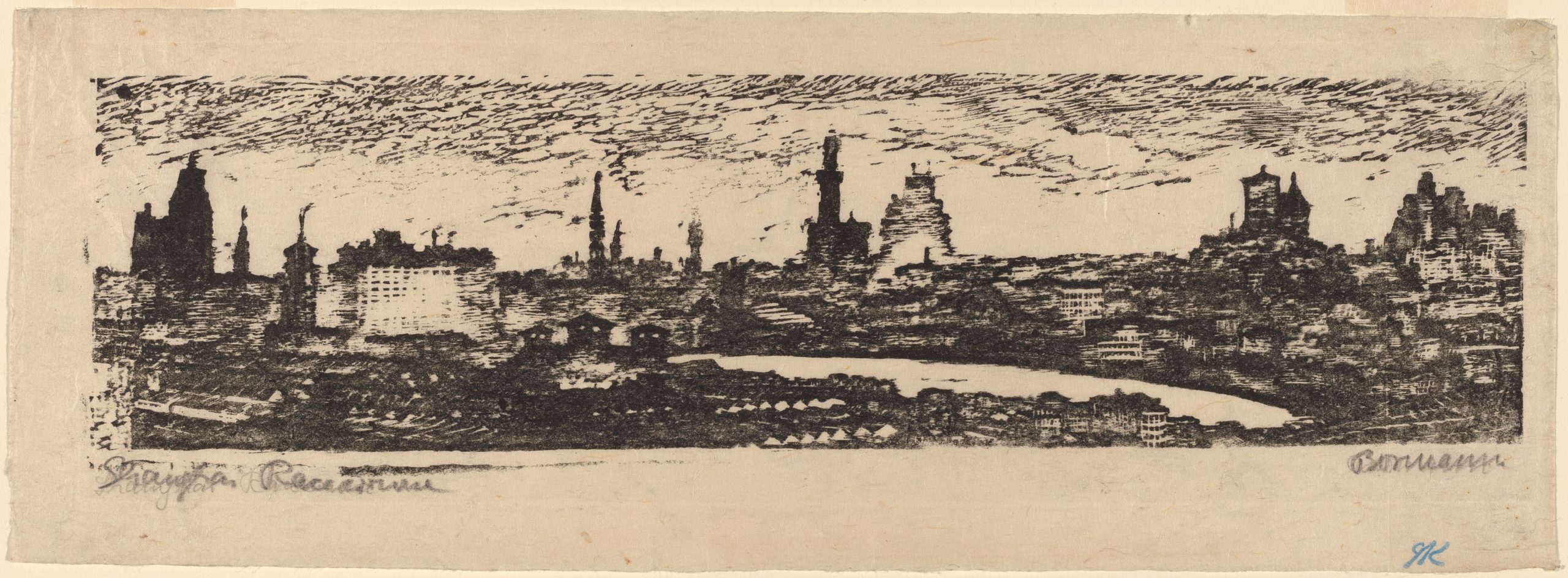

Emma Bormann, Shanghai Racecourse, around 1940, woodcut or lino print (© private collection).

Emma Bormann, Shanghai Racecourse, around 1940, woodcut in black on japan paper, 16,6 x 45 cm (© Gift of Jacob Kainen, National Gallery of Art, Washington).

Emma Bormann, The Bund, around 1940s, woodcut or lino print (© private collection).

Bibliography (selection)

Bergère, Marie-Claire. Shanghai. China’s Gateway to Modernity. Translated by Janet Lloyd, Stanford University Press, 2009.

Bloch, David Ludwig. Holzschnitte. Shanghai 1940–1949, edited by Barbara Hoster et al., Steyler, 1997.

Ebner, Irene, editor. Jewish Refugees in Shanghai 1933–1947. A Selection of Documents. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2018.

Freyeisen, Astrid. Shanghai und die Politik des Dritten Reichs. Königshausen & Neumann, 1999.

Hua, Xiahong, and Michelle Qiao. Shanghai Hudec Architecture. Tongji University Press, 2016.

Hou, Li. Richard Paulick in Shanghai 1933–1949: The Postwar Planning and Reconstruction of a Modern Chinese Metropolis. Tongji University Press, 2016.

Johns, Andreas. The Art of Emma Bormann. Ariadne Press, 2016.

Kaminski, Gerd. Der Blick durch die Drachenhaut: Friedrich Schiff: Maler dreier Kontinente (Berichte des Ludwig-Boltzmann-Institutes für China- und Südostasienforschung, 41). Ludwig-Boltzmann-Institut für China- und Südostasienforschung, 2001.

Karmasin, Mathias, and Christian Oggolder, editors. Österreichische Mediengeschichte, vol: 2: Von Massenmedien zu sozialen Medien (1918 bis heute). Springer, 2019.

Kögel, Eduard. “Ein Knoten im Netz. Richard Paulick in Schanghai.” Netzwerke des Exils. Künstlerische Verflechtungen, Austausch und Patronage nach 1933, edited by Burcu Dogramaci and Karin Wimmer, Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2011, pp. 223–242.

Kögel, Eduard. Architekt im Widerstand. Rudolf Hamburger im Netzwerk der Geheimdienste. Dom Publishers, 2021.

Kranzler, David. “Restrictions Against German-Jewish Refugee Immigration to Shanghai in 1939.” Jewish Social Studies, vol. 36, no. 1, January 1974, pp. 40–60. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4466801. Accessed 12 March 2021.

Pan, Guang. A Study of Jewish Refugees in China (1933–1945). History, Theories and the Chinese Pattern. Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press/Springer, 2019.

Pan, Lynn. Shanghai Style. Art and Design Between the Wars. Long River Press, 2008.

Shih, Shu-mei. The Lure of the Modern: Writing Modernism in Semicolonial China, 1917–1937. University of California Press, 2001.

Suermondt, Rik. “Ellen Thorbecke.” Fotolexicon, vol. 16, no. 32, 1999, n. p. Depth of Field, https://depthoffield.universiteitleiden.nl/1632f06nl/. Accessed 15 January 2021.

Sullivan, Michael. Art and Artists of Twentieth-century China. University of California Press, 1996.

Taylor, Jeremy E. “Cartoons and Collaboration in Wartime China: The Mobilization of Chinese Cartoonists under Japanese Occupation.” Modern China, vol. 41, no. 4, 2015, pp. 406–435. SAGE Journals, doi: doi.org/10.1177/0097700414538386. Accessed 12 March 2021.

Wang, Yiyan. Modern Art for a Modern China. The Chinese Intellectual Debate, 1900–1930. Routledge, 2021.

Yeh, Wen-hsin. Wartime Shanghai. Routledge, 1998.