New York

In the footsteps of German-speaking emigrant photographers in New York City during the 1930s and 1940s

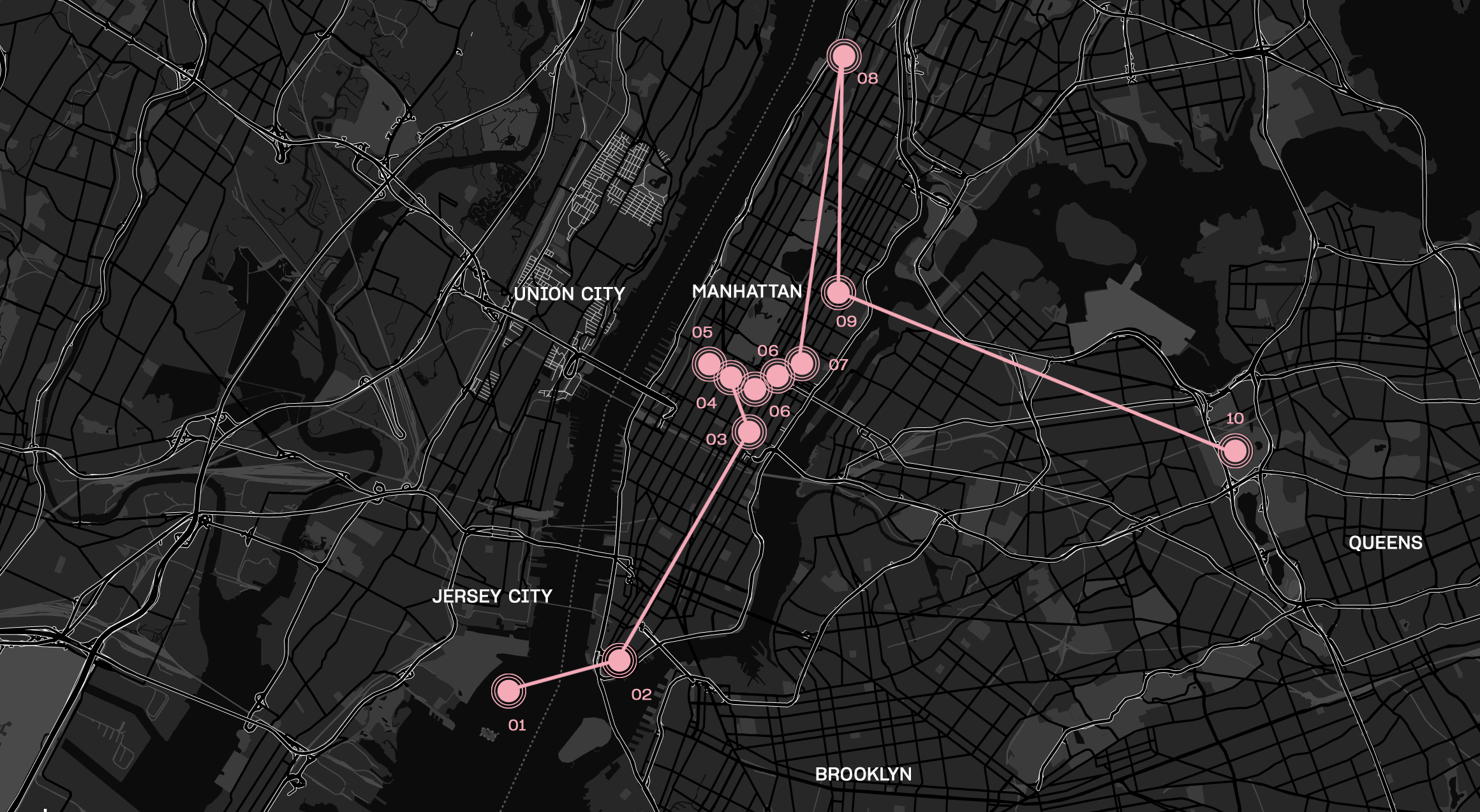

New York was an important destination for artists and intellectuals who had to flee Europe in the 1930s and 1940s. Among them were many photographers who tried to continue their profession in the metropolis. Due to technical advances, cameras were easier to use and affordable in smaller sizes. In contrast to painting or sculpture, the camera’s mobile character allowed to take pictures with less effort and equipment. Furthermore, the newly emerging artistic and photojournalistic scene in New York encouraged many emigrants to turn to photography. Based on research on the emigration of German-speaking photographers to New York during the 1930s and 1940s, this walking tour provides an insight into the lives and artistic works of these émigrés. The aim of its 10 stops is to show how emigrated photographers were intertwined with both American and exiled society, as well as with the artistic, cultural and gastronomic environments in New York. The walk sheds light on a rich visual urban history in today’s cityscape.

miles 420

min. 10

sights ship / train

01Ellis Island/ New Jersey

As most emigrants arrived in New York on ship, the walking tour starts from Battery Park with a trip to Ellis Island. Only ten minutes after departure, the skyline with the Statue of Liberty emerges. A photograph by Lotte Jacobi shows this important moment of arrival. During the 1920s Jacobi had lived in Berlin with her family, where she worked with her sister in her parent’s photo studio. In 1935, she came to New York on a visitor’s visa from Southampton. She had left London, the first station of her exile, after three weeks, as the situations for emigrants in Great Britain became increasingly difficult. The photograph shows her arrival with a view of the New York skyline from the ship. Jacobi is one of the few photographers who captured the arrival on camera.

Arrival on the ship Georgic in New York on September, 29 1935 by Lotte Jacobi (© Estate Lotte Jacobi, New Hampshire).

Opened in 1892, Ellis Island was the immigration station and deportation centre where – depending on immigration laws and quota – certain nations or conspicuous emigrants were detained. In the 1930s and 1940s the passenger status was decisive for whether one was to depart directly on the piers in New York harbours (today’s Hoboken and Chelsea Piers) or was sent to Ellis Island. This was the case for steerage and 3rd class passengers or emigrants without valid immigration papers. To obtain the resident permit for the United States, émigrés had to pass several line inspections, examinations and bureaucratic steps, which could last from 5 hours to several days and weeks. From the 1940s on until 1954, the island served as a detention centre where emigrants who had been living in New York for several years and Enemy Aliens were held, due to incorrectly fulfilled legal requirements at the time of immigration. In their pictures and portraits, American and European (émigré) photographers such as Lewis Hine, Margaret Burke-White, Erich Salomon, Werner Wolff or Erika Stone focused on the tense atmosphere on the island. If you have time, take a 20-minute trip to Ellis Island and the Immigration Museum. Otherwise take a virtual tour and visit the Oral History Collection or research your own past or certain names with the help of the Passenger Search database.

View from the boat to the Statue of Liberty and Manhattan’s skyline (Photo: Helene Roth, 2018).

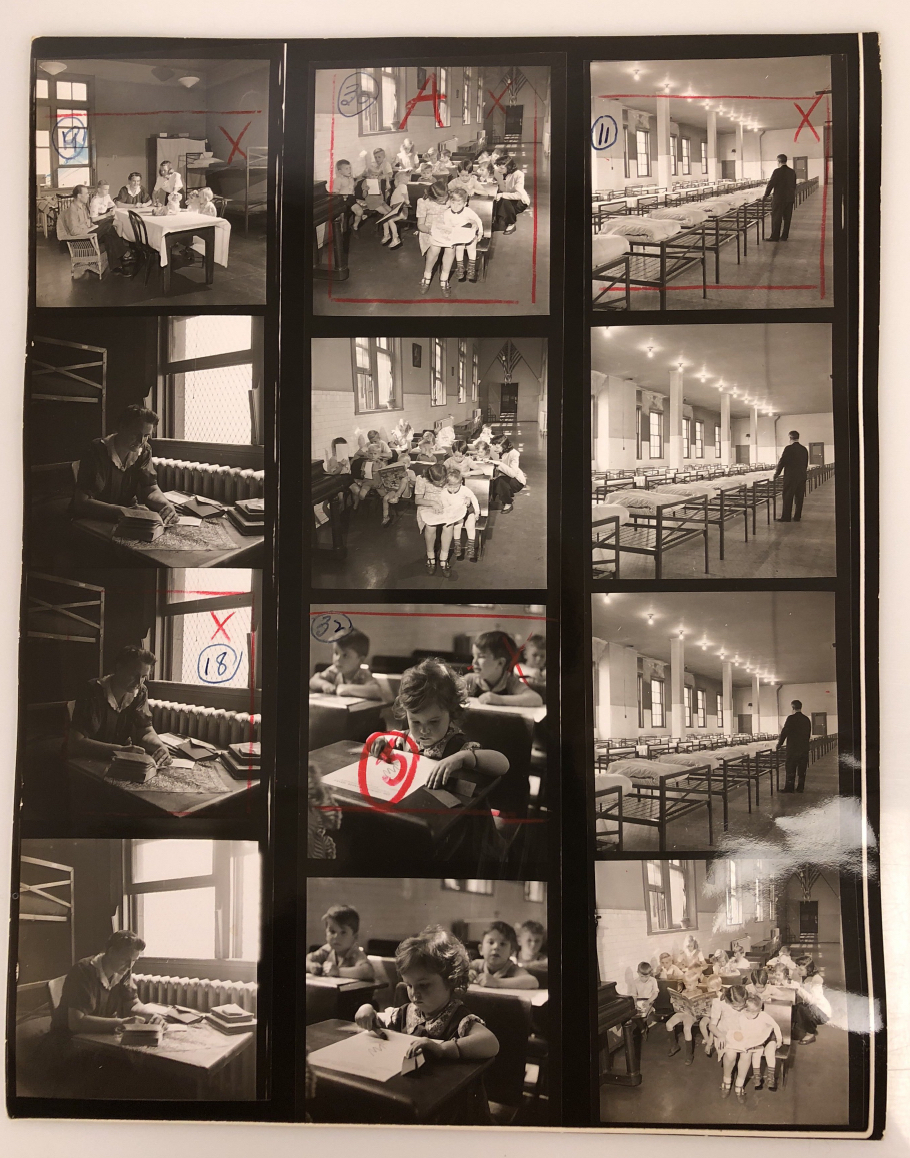

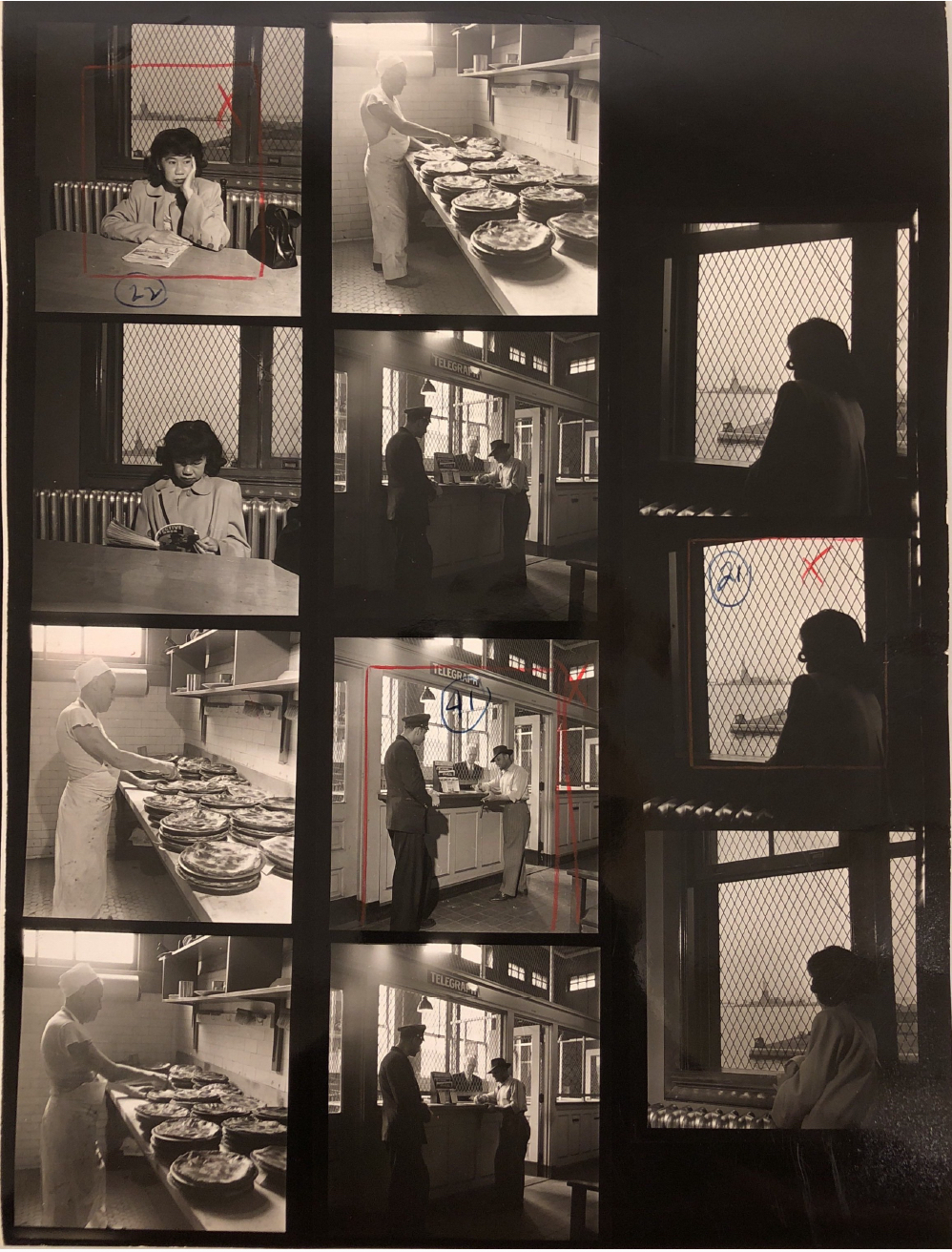

In 1949, Werner Wolff, who emigrated to New York in 1936 and who was able to continue his career as photographer for several photo agencies, created an Ellis Island photo story. He captured the different parts of the building such as the entrance hall, library and school room, as well as several portraits of people from all over the world held on the island.

Contact sheets of Werner Wolff’s photo series on Ellis Island, 1949 focussing children of detained aliens attending school taught by a volunteer member of the Social Service (© The family of Werner Wolff / Ryerson Image Center).

Backside of the contact sheet with creditline and stamp of the photo agency Black Star (© The family of Werner Wolff / Ryerson Image Center).

Contact sheets of Werner Wolff’s photo series on Ellis Island, 1949 in commission for the photo agency Black Star of a Dutch East Indian woman looking through barred windows, Ellis Island kitchen and the entrance hall (© The family of Werner Wolff / Ryerson Image Center).

02Coenties Slip/ 74 Pearl Street

It’s hard to envision that right here the elevated railroad (El) on the former Second and Third Avenue train lines ran around the corner of the Coenties Slip and Pearl Street. The streetscape and the urban landscape were radically shaped by the El. A picture by the emigrated photographer Andreas Feininger gives us an impression of how the mystical construction of steel meandered high across the narrow bend and ran level to the first and second floors of the buildings. Built in 1878, the 2nd Ave. El was one of the four lines (Second, Third, Sixth and Nine Ave.) that was constructed during the 1870s in the hopes of solving New York’s transit problems and crowded streets. The S-Curve was originally located on today’s corner of 2 Coenties Slip, aka 74 Pearl Street. With the construction of the subways, however, the 2nd Ave. El was demolished in 1942, and the 3rd Ave. El in 1955.

Andreas Feininger focusing on 2nd Ave Elevated at Coenties Slip, 1940 (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

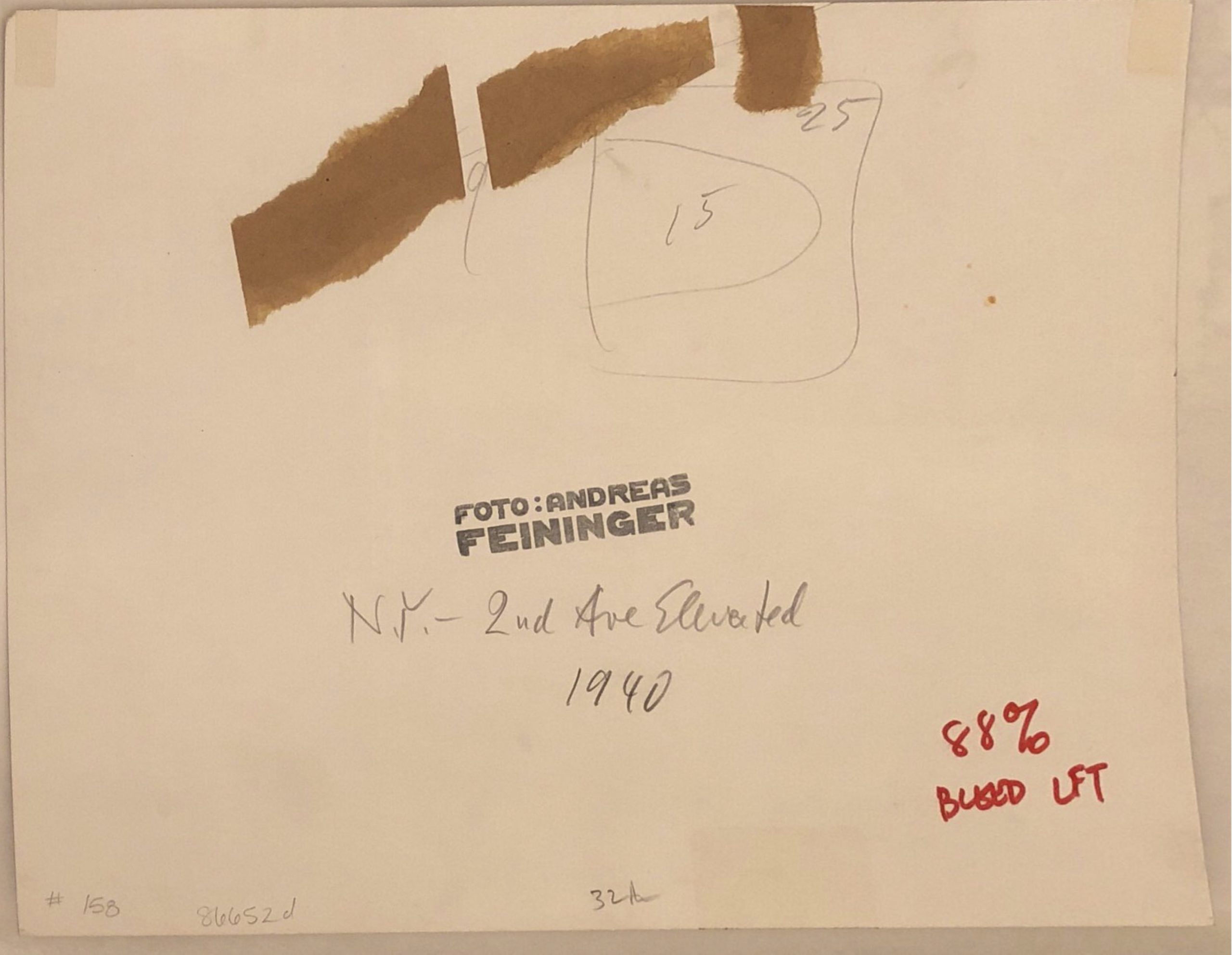

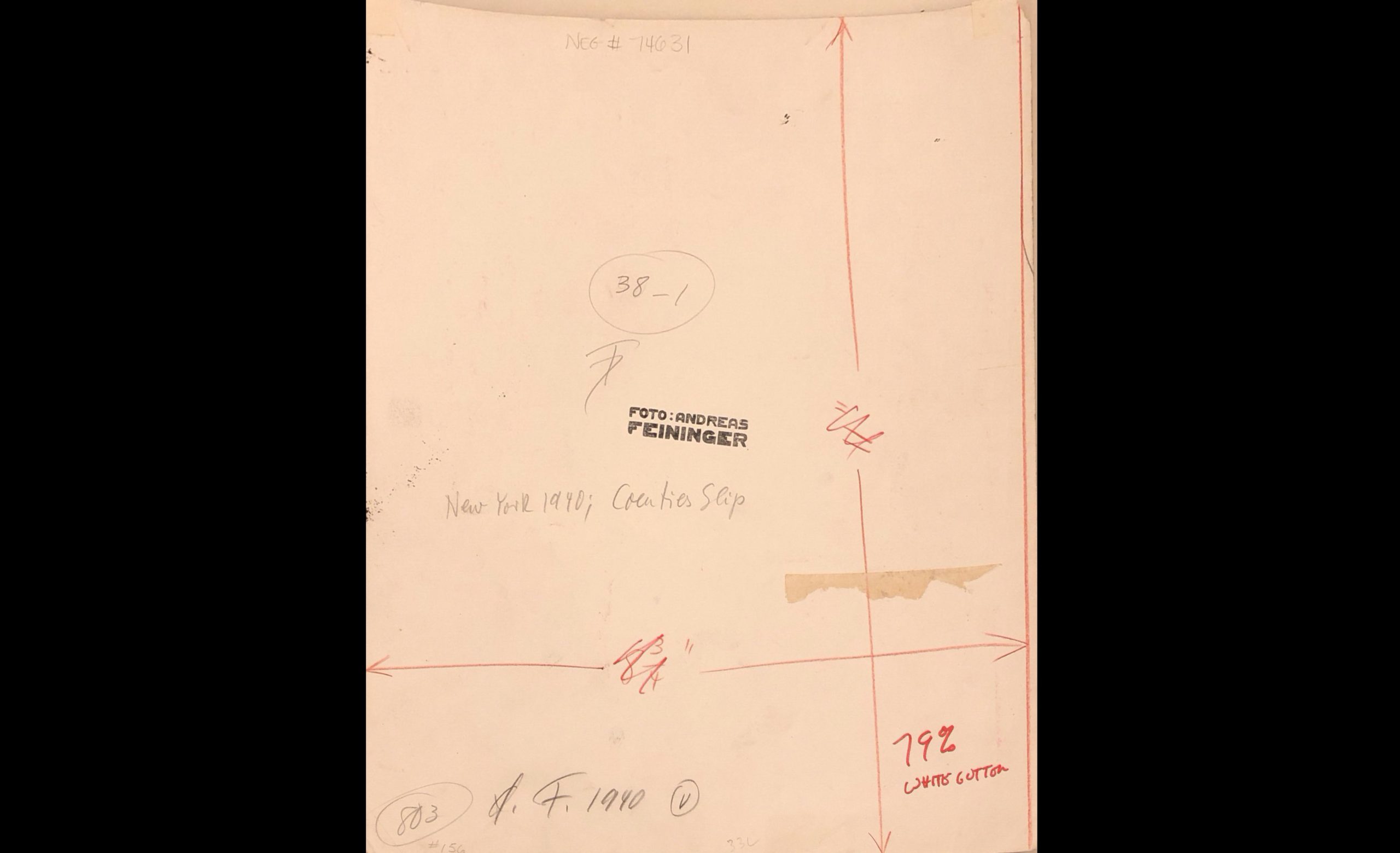

Backside of N.Y. – 2nd Ave Elevated by Andreas Feininger with stamp and caption, 1940 (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

Andreas Feininger focusing on Coenties Slip, 1940 (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

Backside of New York 1940; Coenties Slip by Andreas Feininger with stamp and caption (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

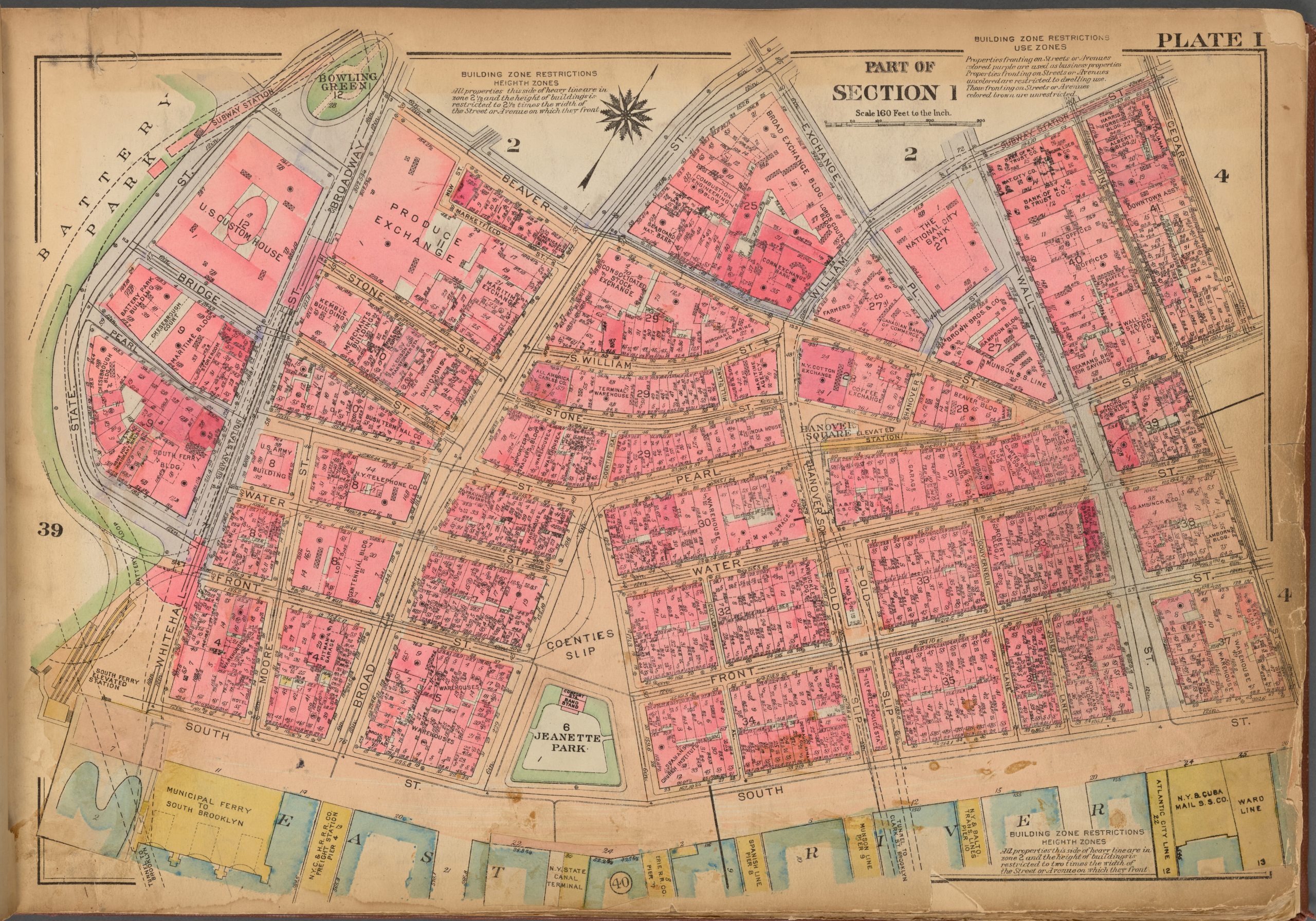

Bromely Map of this area, 1921/23 (Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections).

If you look around the corner (or examine the Bromley city map), you will realize how close the elevated S-Curve was to the buildings at the time. You are standing where it turned into Pearl Street. Andreas Feininger also stood right in the middle of Coenties Slip when he took the photograph of this elevated curve which today is an invisible trace of New York’s history.

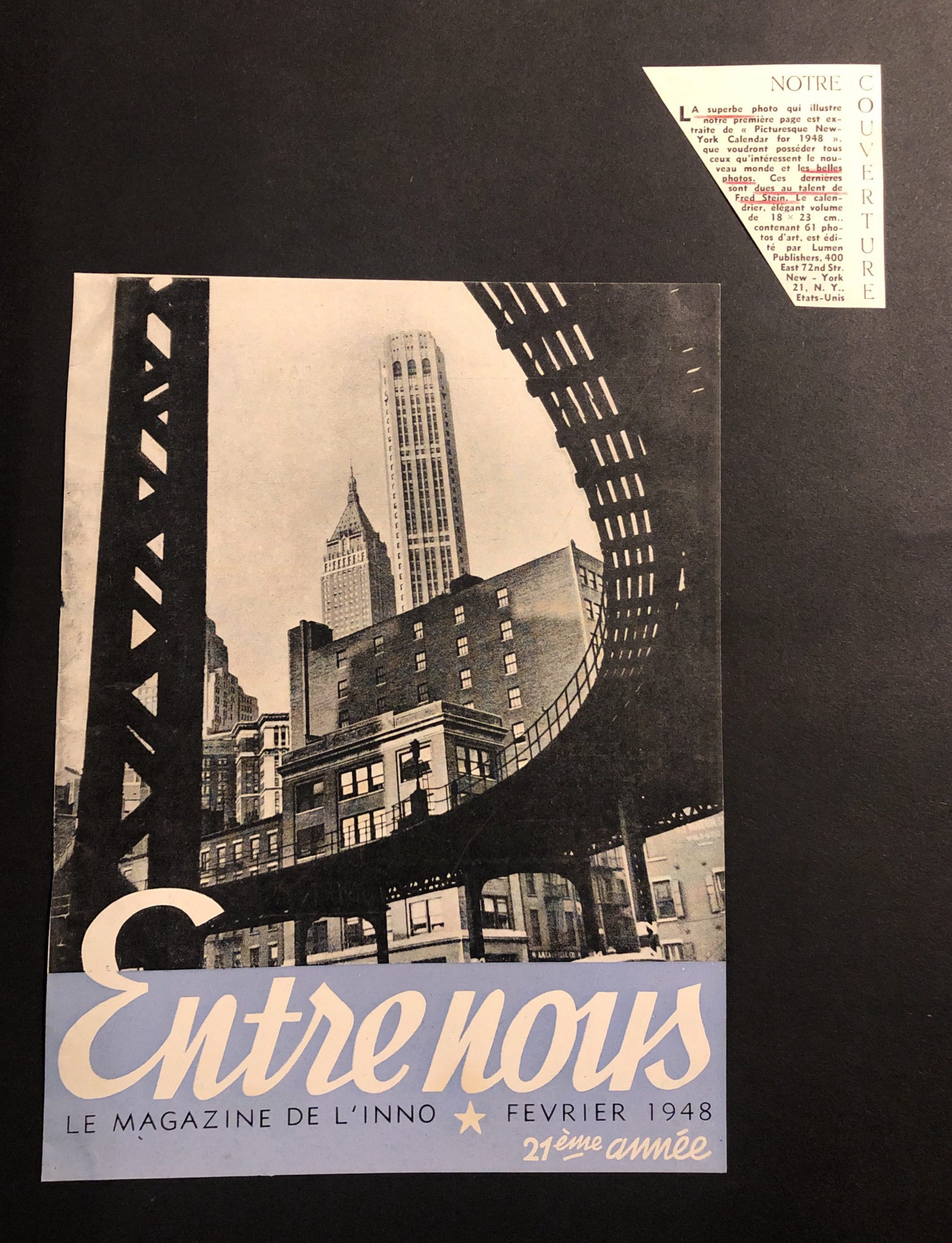

Emigrated to New York from Germany via Paris and Stockholm in 1941, Andreas Feininger was very attracted by the city’s architecture and took several hundred pictures of the metropolis. His photos were mostly planned in advance, by studying historical and contemporary maps, by pinpointing the light conditions and the atmosphere for the precise moment of the day, as well as by considering other factors such as rush hours. Working with a Rolleiflex camera, he was able to handle the apparatus in front of his body in dynamic ways and to facilitate the redistortion of converging verticals to parallelism in architectural motifs. Feininger was soon joined by other emigrated photographers, such as Fred Stein, who would stand at the same spot, equally fascinated by its specific atmosphere and urban transportation system that was – as foreigners – new to them. Fred Stein’s photo was used as cover for the French Entre-Nous magazine. His impressions of the spatial architectural dimensions were therefore recognized by an international readership.

Fred Stein’s photo of Coenties Slip, 1946 (© Estate Fred Stein).

Cover of French magazine Entre-Nous with a photograph by Fred Stein, February 1948. A little note on the inside informs the reader that this photo is also part of Fred Stein’s calendar Picturesque New York (Lumen Publisher, 1948) (Photo: Helene Roth, 2019 © Estate Fred Stein).

Besides these photographs, the Coenties S-Curve can also be discovered in documentaries like in the short film 3rd. Ave. El (1955, Carson Davidson). The film follows the route of the Third Avenue Line through Manhattan. At minute 2 you can get a feeling for how the train ran through the S-Curve. The music is Haydn’s Concerto in D, played by the Polish harpsichordist Wanda Landowska, who emigrated to New York in 1941. For the first time ever in the twentieth century, Landowska performed Bach’s Goldberg Variations with her harpsichord (the instrument for which it was originally written) at New York’s Town Hall in 1942. In the 1950s, the émigré photographer Herman Landshoff made a series of Landowska in her home in Connecticut focusing on her long and flexible fingers – as the source and tool for her music.

Film 3rd Ave. El (Carson Davidson, 1955) (© The Academic Film Archive of North America). Duration 10:58, excerpt

Hermann Landshoff: Die Hände von Wanda Landowska, 1951 (© bpk / Münchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung Fotografie / Archiv Landshoff).

03Graybar Building/ 420 Lexington Avenue

Manhattan’s flourishing media-press scene, bolstered by magazines and newspapers such as Life, Harper’s Bazaar, Look, U.S. Camera, Popular Photography, New York Times or Fortune, needed a lot of photographic material for its publishing avenues. The immigrant visa to the United States allowed full employment and enabled emigrants to found businesses. For this reason, there are quite a lot of photo agencies initially established by emigrated photographers, photo editors and entrepreneurs. The Black Star Agency was founded in 1936 by the three German émigrés Kurt S(z)afranski, Ern(e)st Mayer and Kurt Kornfeld. The agency was located in the Graybar Building at 420 Lexington Avenue. The Art-Deco 30-floor office building, designed in 1927, is an integral part of the Grand Central Terminal that connects the station with Lexington Avenue. All three men lived in New Rochelle with their families, from where they took the New Haven Line to Grand Central Station every morning. Without leaving the terminal, they could enter the Graybar Building, which at the time was the largest office building in the world. With the economy depleted after the Great Depression, many buildings stood empty. It is for this reason that Black Star did not have to pay any rent for the first six months. Today, the Graybar building is still connected to the Central Station and holds a wide range of different offices. Take a look and find the passageway to the station!

Facade and entrance of the Graybar Building on Lexington Avenue; (Photo: Helene Roth, 2018).

Inside view with entrance facing Grand Central Station (Photo: Helene Roth, 2018).

The aim of the photojournalistic agency was to foster an economic network between photographers and the magazines/newspapers developing new visual aesthetics for photo stories. The funding of such collaborations benefitted from the large amount of press images that had “emigrated” from Ernest Mayer’s previous photo agency Mauritius in Berlin to New York (the pictures can be found in the Online Collection of the Ryerson Image Center). Kornfeld and Safranzki had already been embedded in the German publishing and media sector in the 1920s. Kornfeld worked as an editing publisher and Safranski was the manager of the Ullstein magazine publishing house in Berlin. The “black star” logo and stamp can nowadays be found on the backside of many photos taken by émigré photographers working for and with the agency. Among them are Fred Stein, Walter Sanders (Süßmann), Ruth Bernhard, Andreas Feininger, Fritz Goro, Ilse Bing, Fritz Henle, Herbert Matter, Roman Vishniac, Lilly Joss Reich, Trude Geiringer, Lisa Rothschild (Larsen), Kurt Severin, Werner Wolff and many more. For all of them, Black Star, as a German-speaking agency, was a great starting point to earn money with photography shortly after their respective arrivals to the US as well as to enter the photojournalistic scene in New York.

Letterhead with the logo and address of Black Star (© Estate Fred Stein).

During the 1940s, Black Star established a well running photo agency and profited from the central location in Midtown Manhattan in the immediate vicinity of other photo agencies, publishing houses and photo labs. Quite a few of them were also founded by emigrants. Even the proximity to the Grand Central Station was important for sending and receiving photos via train. Interestingly, other photo agencies like Ewing Galloway, the Amateur Cinema League and the media headquarter of Condé Nast (Vogue, Glamour) as well as magazines like This Week Magazine, U.S. Camera or Esquire had their offices in the Graybar Building. This cumulation of photo agencies and media outlets had the great effect that picture agents could directly go from business to business while merely changing floors.

Letterhead of This Week Magazine located at 420 Lexington Avenue (© Estate Fred Stein).

Letterhead of Amateur Cinema League, Inc. located at 420 Lexington Avenue (© Estate Fred Stein).

Letterhead of U.S. Camera Publishing Corporation located at 420 Lexington Avenue (© Estate Fred Stein).

Letterhead of Vogue. The Condé Nast Publications Inc. located at 420 Lexington Avenue (© Estate Fred Stein).

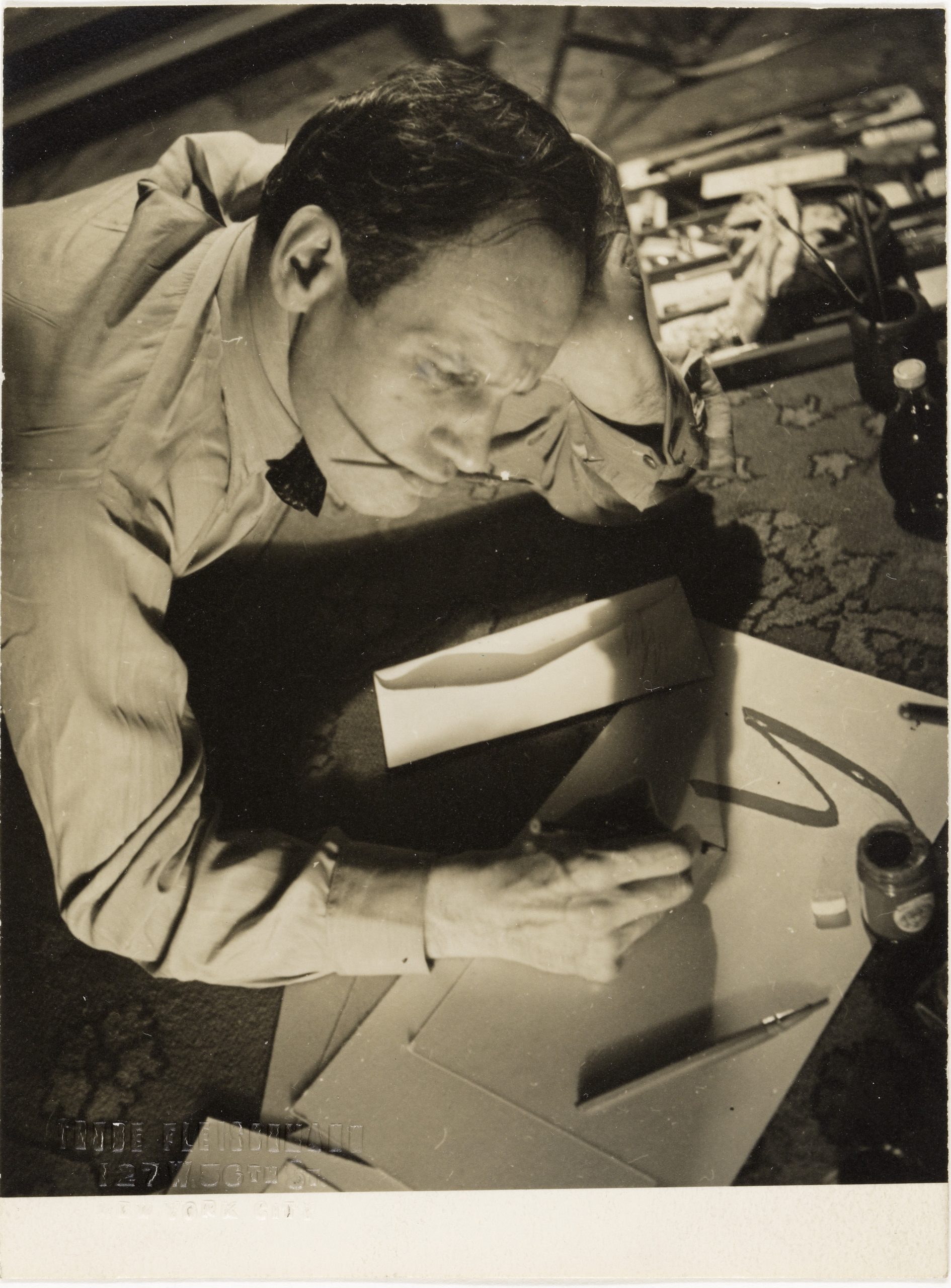

04Photo studio Trude Fleischmann and Frank Elmer/ 127 West 56th Street // Carnegie Hall, 881 7th Avenue

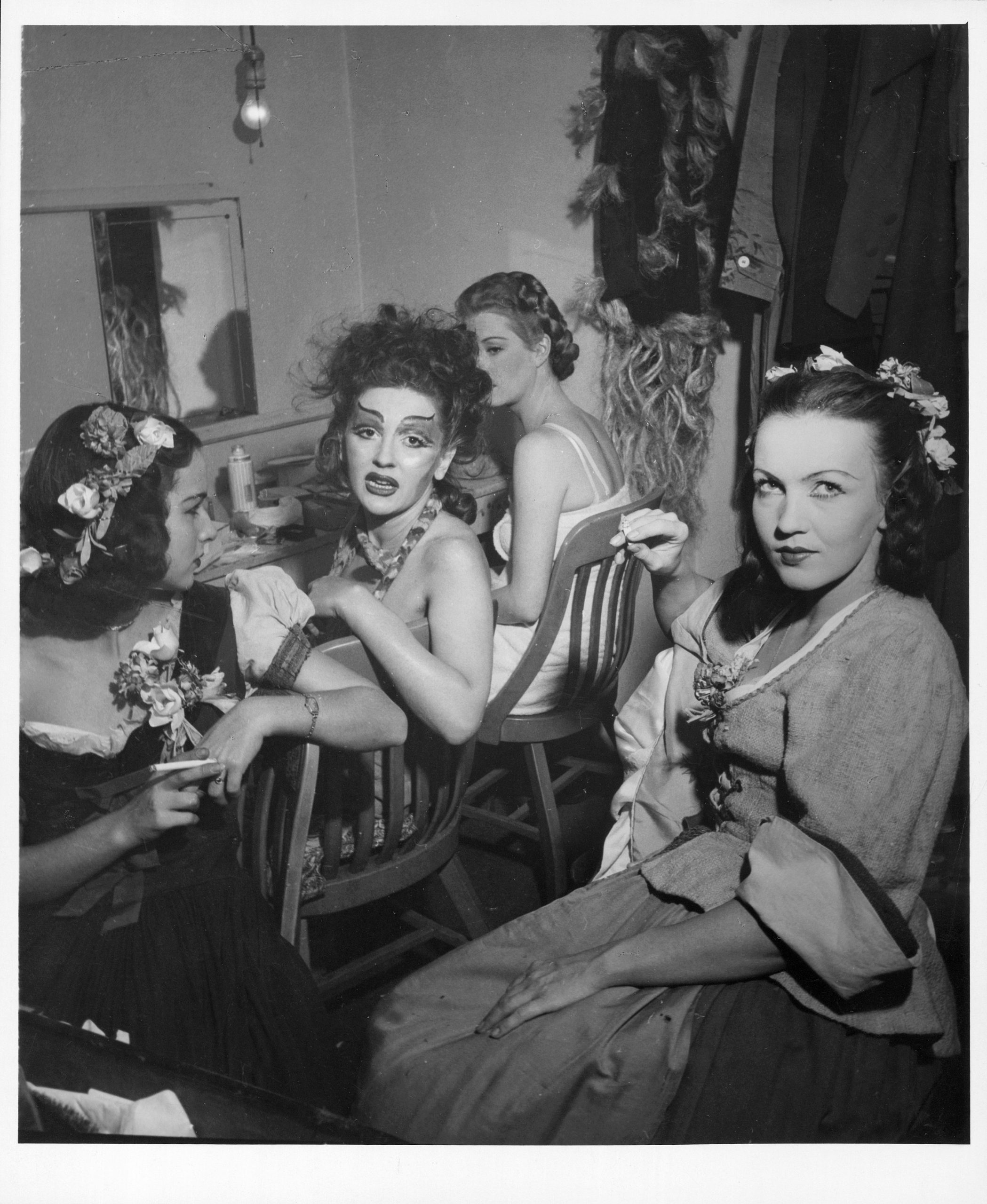

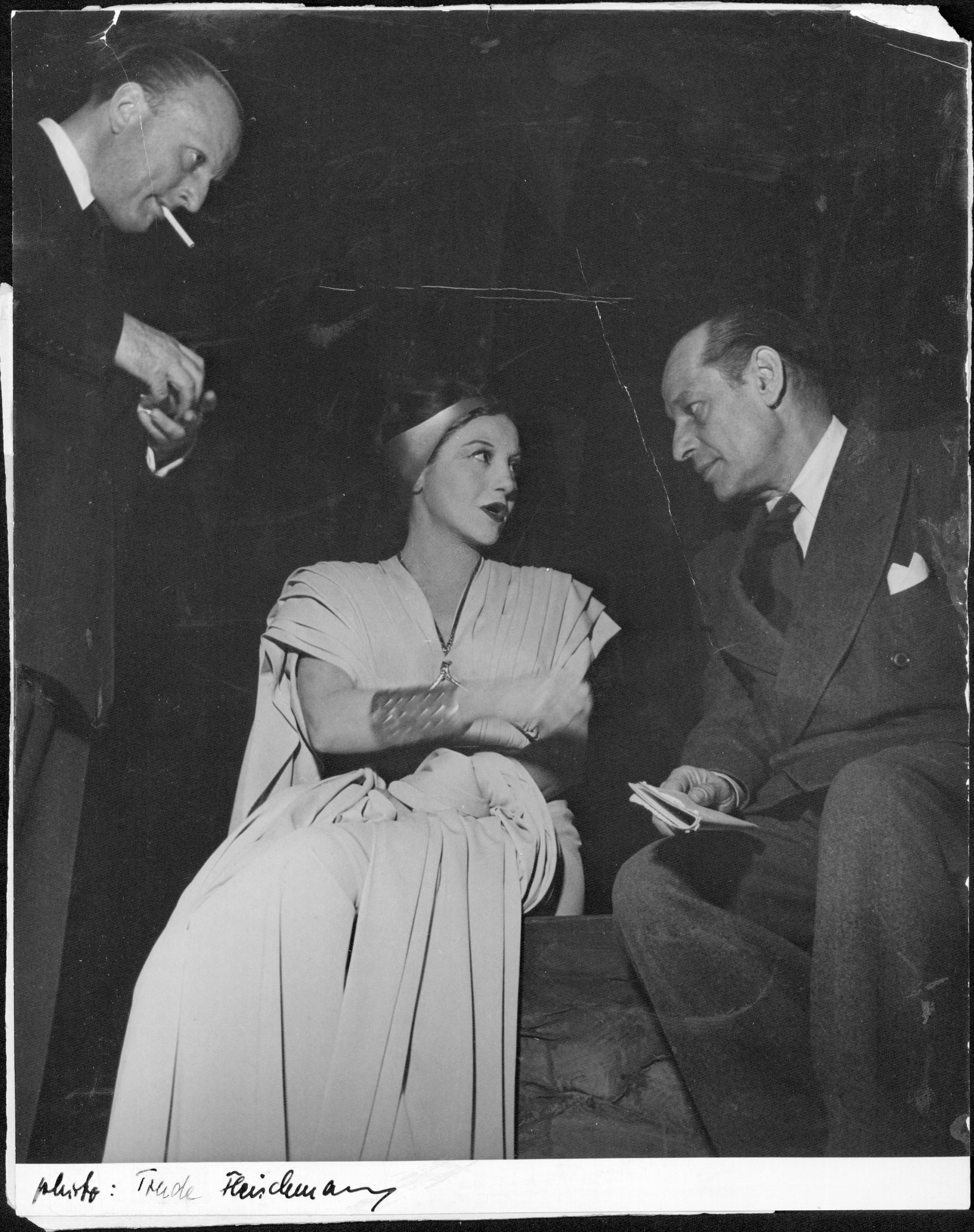

Many of the photo studios founded by emigrated photographers were located between the area of the 8th and Park Avenue around Central Park. Here, too, we must assume that the consequences of the Great Depression affected the low rents in these central – and now unaffordable – locations in Manhattan. Together with her Viennese émigré colleague Frank Elmer, the Austrian-born Trude Fleischmann opened a photo studio on 127 West 56th Street in 1939. The 40m2 room was also where they lived and was located in the pulsating theatre and music district. Close to them were a number of studios led by other female émigré photographers such as Lotte and Ruth Jacobi, Ylla or Gerda Peterich. While re-establishing herself as a studio photographer, Fleischmann also went out into the city portraying émigré artists and intellectuals. Often, she already knew her subjects from her time in Vienna, like the actress Elisabeth Bergner. Bergner emigrated to the US via London in 1940 and was part of the German emigrant ensemble “Players from Abroad”. Founded in 1942 by Gert von Gontards and Felix Gerstmann, the ensemble was for a long time the only German-language theatre in the United States.

Group portrait behind the scene of “Players from Abroad”, photographed by Trude Fleischmann (© Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933-1945, Frankfurt am Main).

Portrait of Gert von Gontard, Elisabeth Bergner and Felix Gerstmann for the performance Iphigenie auf Tauris, photographed by Trude Fleischmann, 1947/48 (© Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933-1945, Frankfurt am Main).

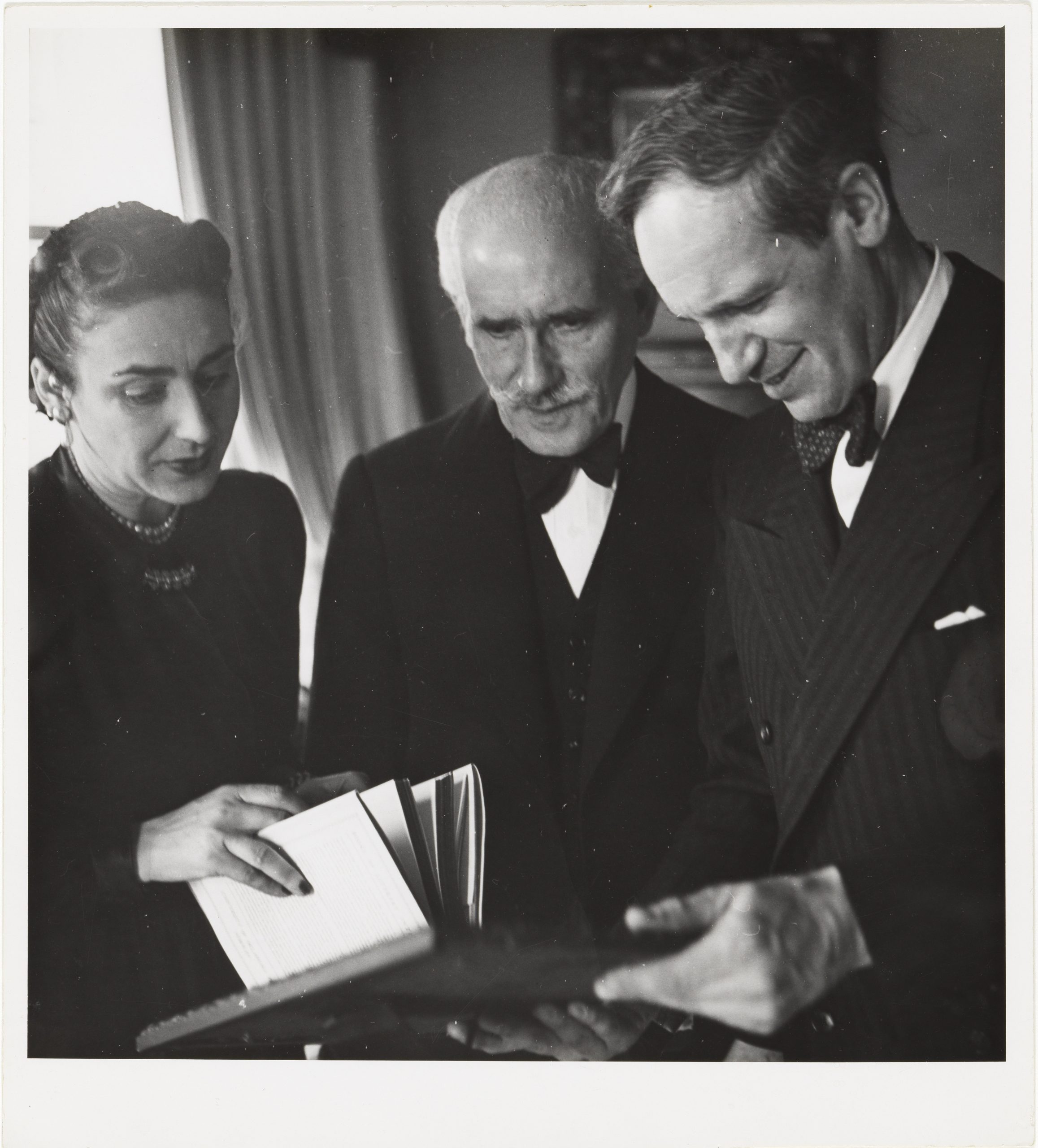

Fleischmann’s studio was directly located next to Carnegie Hall. She often went there to attend concerts and portrayed famous musicians and conductors such as the Italian émigré Arturo Toscanini. From this encounter a long friendship documented in various photo series developed which lasted until his death in 1957.

Arthur Toscanini und Robert Haas photographed by Trude Fleischmann in 1946 (© Wien Museum / Foto Birgit und Peter Kainz).

Robert Haas was a former student of Trude Fleischmann's and emigrated to New York from Vienna via London in 1938. Here, Trude Fleischmann captured the photographer during the 1940s/1950s (© Wien Museum / Foto Birgit und Peter Kainz).

The Carnegie Hall was also an important location for the jazz label Blue Note. On December 23, 1938, the two German émigrés Francis Wolff and Alfred Lion attended the great concert From Spirituals to Swing and connected with New York’s recording scene. In early 1939, Lion and Wolff launched their own jazz label Blue Note. The aim was to create a style distinctive from the current record labels which focussed on the glossy sound of swing bands. Many of the Blue Note jazz musicians were African American and were able to enter the music scene with the help and support of Wolff and Lion. After his military service in 1943, Francis Wolff began photographing the musicians during their sessions and recorded visually the jazzy moments of Blue Note in New York. His portraits were often used for the sleeves and ushered in a new decade of cover design.

Sidney Bechet’s version of Summertime cut at the third Blue Note Session on June 8, 1939, was the label's first big hit.

On the label’s 80th anniversary, the documentary film It Must Schwing! The Blue Note Story (Eric Fiedler, 2018) combined inspiring music recordings with archival material. As Lion and Wolff never lost their German accent, they gave the instruction “It Must Schwing!” to the musicians – an expression iconic today.

05Joseph Pilates Studio/ 939 8th Avenue

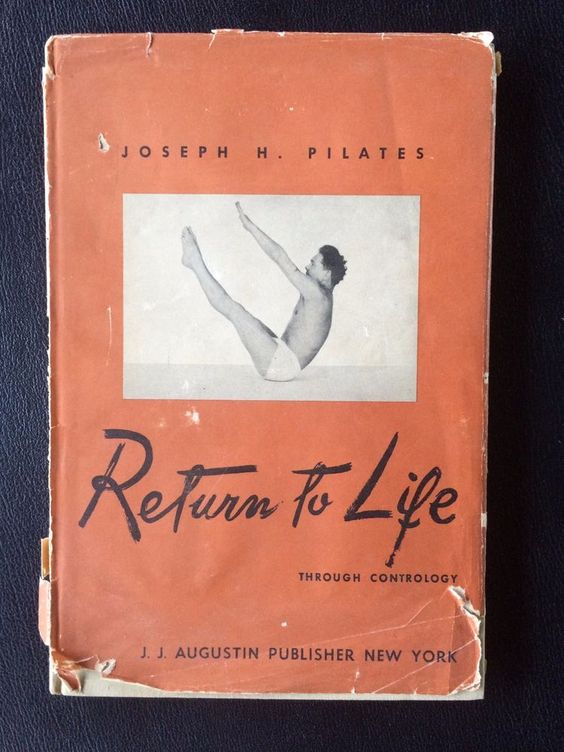

Émigré photographers not only captured the theatre and music scene, but also the growing network of emigrant dancers and trainers. One meeting place was the studio of Joseph Pilates, where now-famous methods for physical fitness were developed. Together with his wife Clara, Joseph opened his first studio on the first floor of 939 8th avenue in 1927. Both were emigrants from Germany and met during their ship passage to New York, where they arrived in April 1926. In Germany, the gymnast and boxer had already recognized the importance of strengthening certain muscle groups and built his own training and exercise equipment to make muscles work against a resistance. In New York, he further expanded the patents for his wood and leather machines.

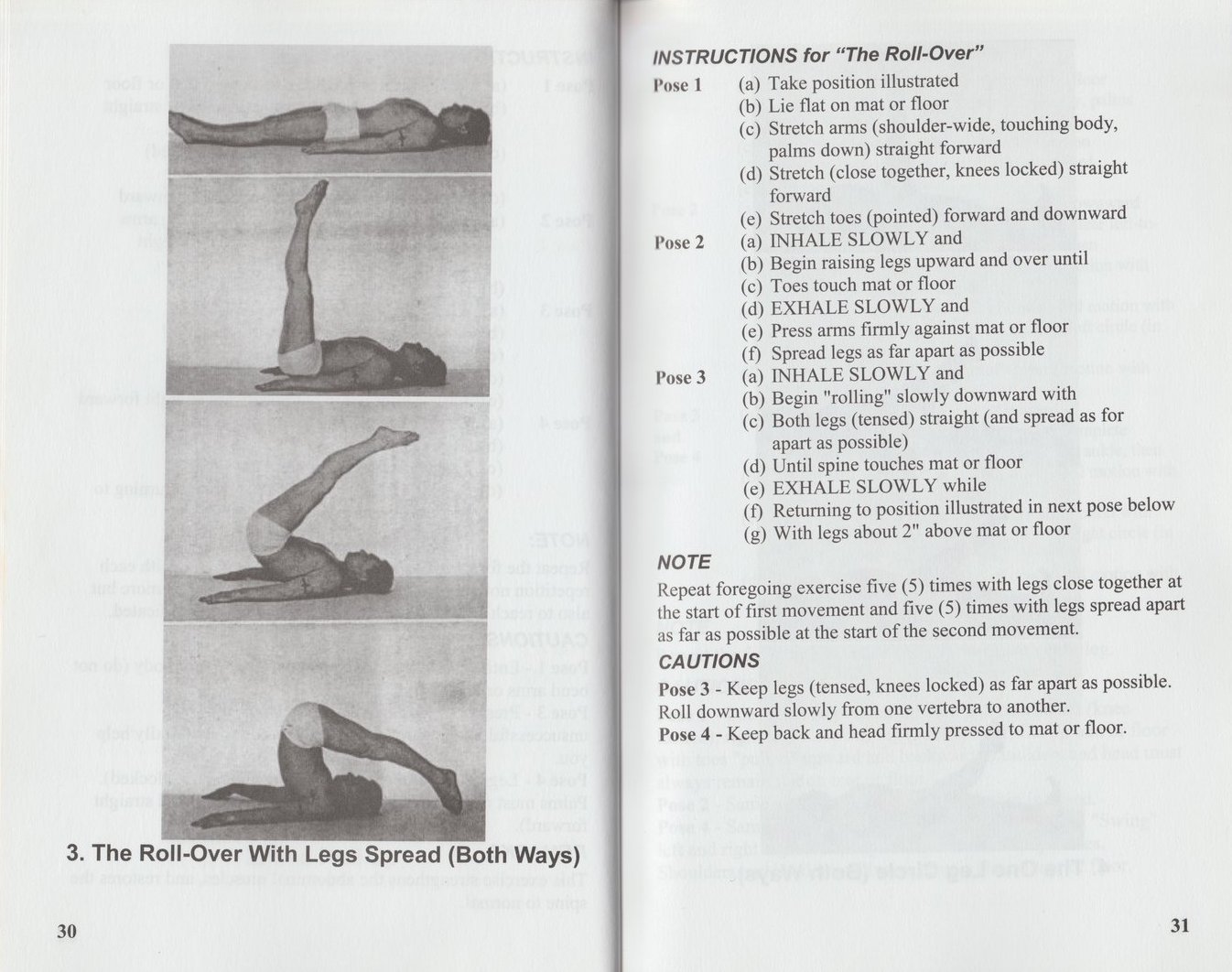

In 1945 Joseph Pilates published his book Return to Life Through Contrology (1945, J.J. Augustin).

The émigré fashion photographer George Hoyningen-Huene took the images for Return to Life Through Contrology (1945, J.J. Augustin). A detailed description of the book is written by Eva Rincke

In 1937, the emigrated photographer Lotte Jacobi made a series of the German émigré dancer Hanya Holm during a group exercise. Photographing from different angles, she went with the flow of the dancers while capturing their gaze and movements. To emphasise the expressive movements of the dancers, she cleverly played with falling light and shadows. Holm was one of Mary Wigman’s former students, one of the founders of the German Ausdruckstanz. From 1931 onwards, Holm directed the Mary Wigram dance school in New York (which was later re-named Hanya Holm dance school). The school was just around the corner of the Pilates studio and because of a leg injury Holm began visiting the studio in the 1930s. Pilates’ training and stretching methods both appealed to and helped Holm. Other dancers and choreographers (such as the Russian émigré George Balanchine, who established the New York City ballet) also sent numerous dancers to the studio, benefiting from its methods for rehabilitation and muscle building.

Mary Wigman photographed by Lotte Jacobi (© Estate Lotte Jacobi, New Hampshire).

Hanya Holm's dancing group photographed by Lotte Jacobi, 1937 (© Estate Lotte Jacobi, New Hampshire). Together with her sister, Lotte Jacobi opened her first photo studio in October 1935. In September 1936, after obtaining her visa, she was able to open her own studio on Central Park 24.

Further image of the series of Hanya Holm’s dancing group by Lotte Jacobi, 1937 (© Estate Lotte Jacobi, New Hampshire).

06Photo Gallery District: Norlyst Gallery, 59 West 56th Street/ Wehye Gallery, 794 Lexington Avenue

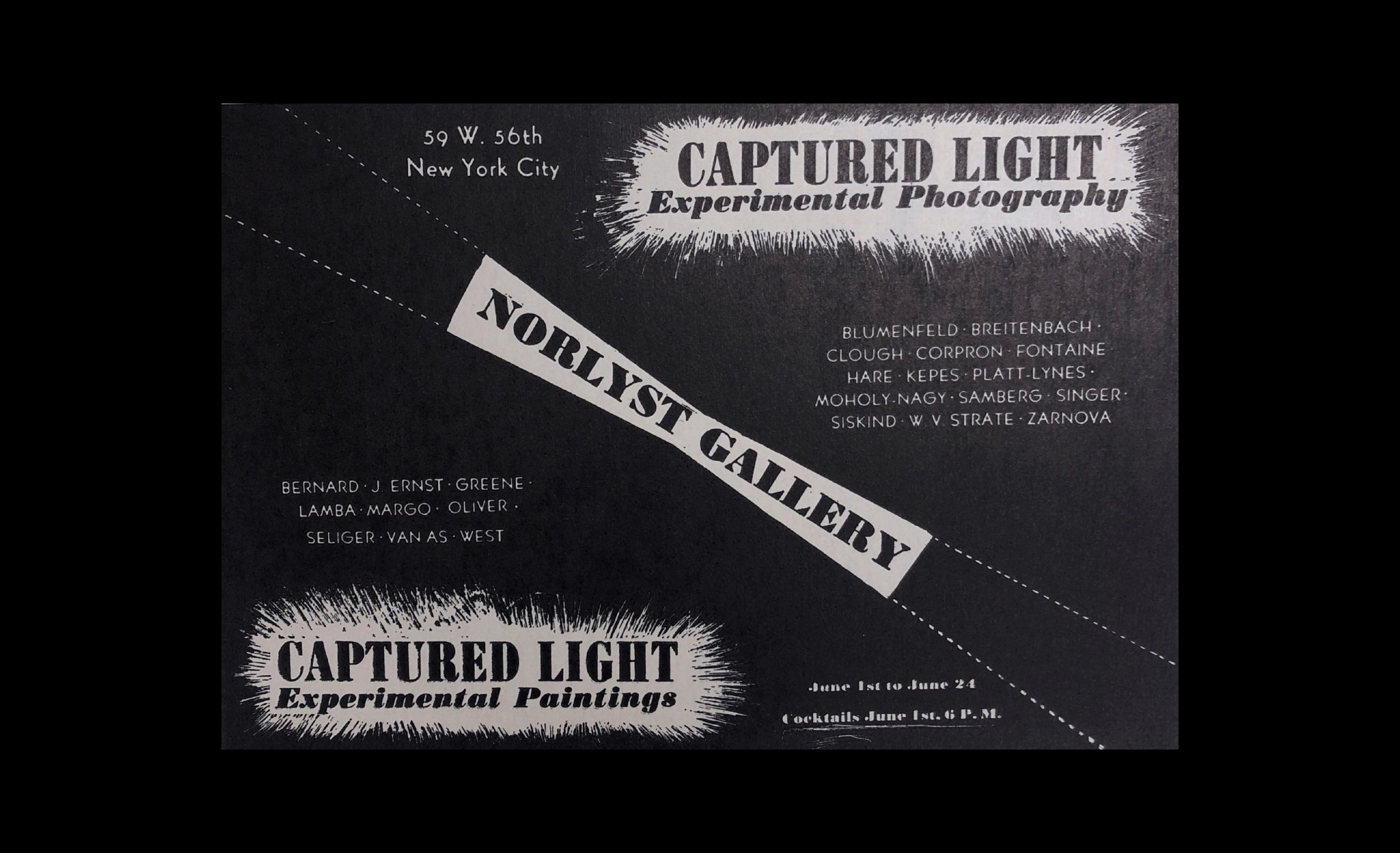

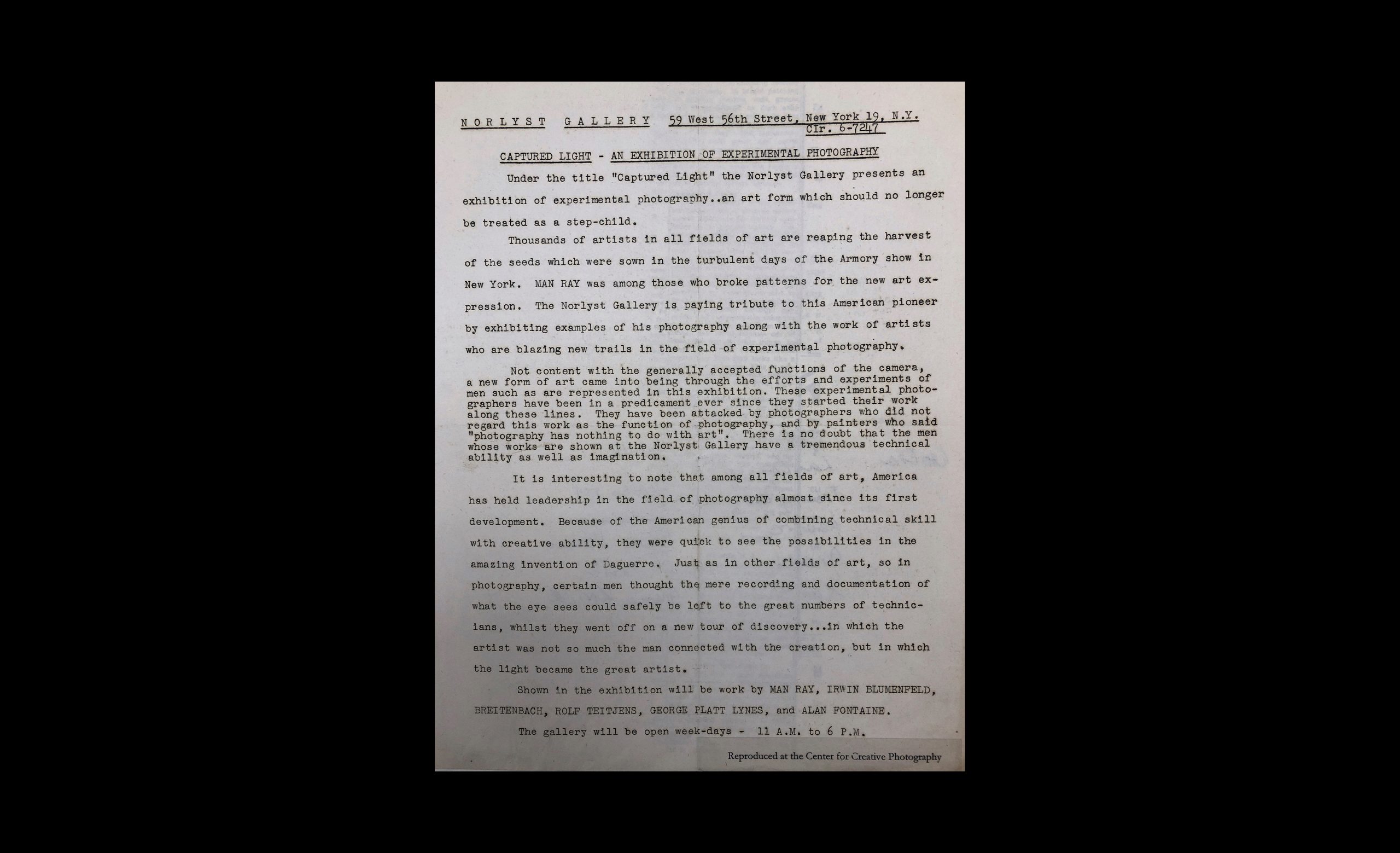

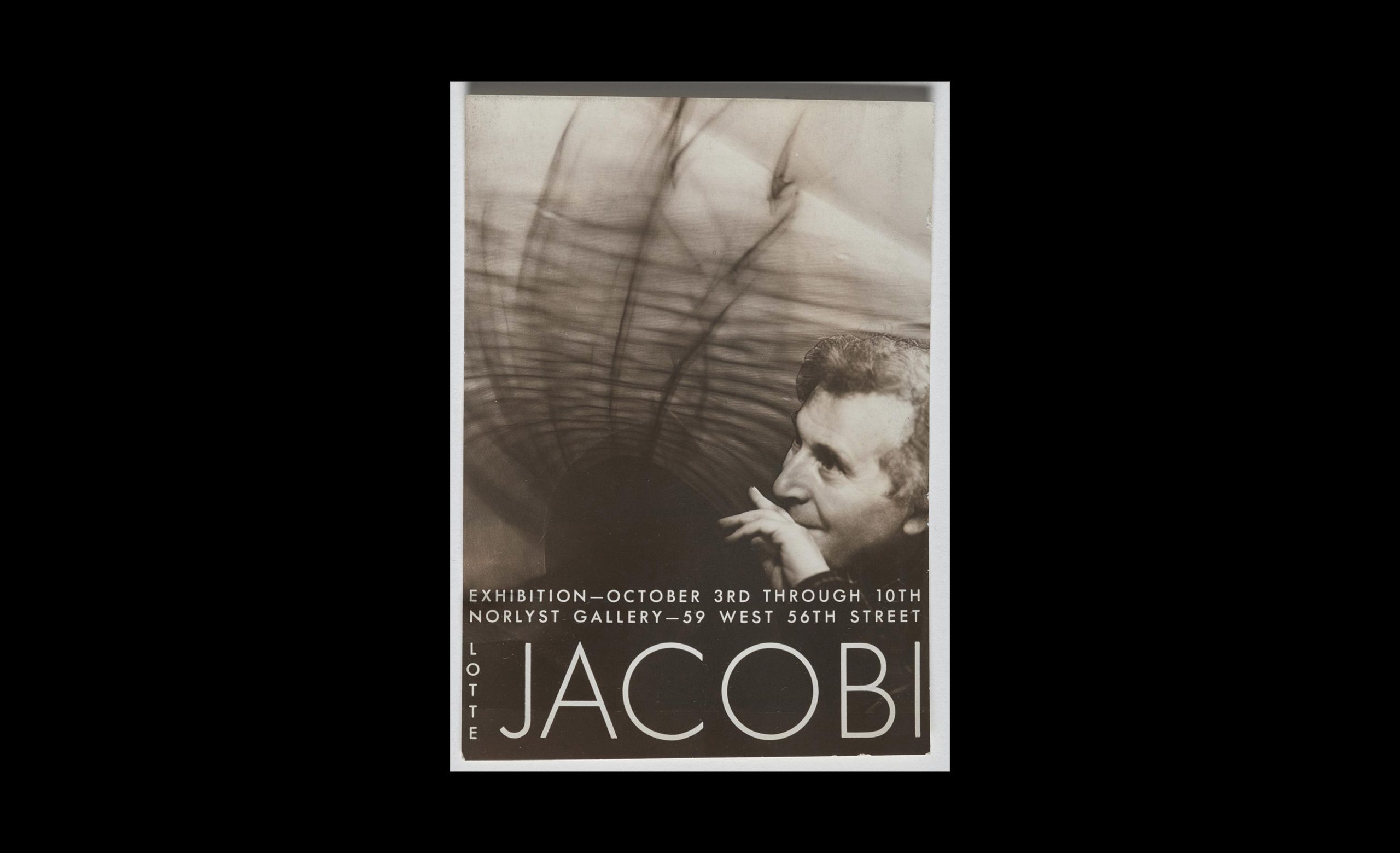

Several galleries in the eastern district between the 6th and Lexington Avenue supported the photographic work of European émigrés. From June 1 to June 24, 1944, the exhibition “Captured Light. Experimental Photography” at the Norlyst Gallery featured the work of several photographers; among them were the émigrés Joseph Breitenbach, Erwin Blumenfeld, Rolf Tietgens, György Kepes and Lazló Moholy-Nagy. The group show was one of the first that presented experimental photography in a gallery – as the exhibition announcement stated in support of this undervalued photographic form: “These experimental photographers have been in a predicament ever since they started their work […] They have been attacked by photographers who did not regard this work as the function of photography, and by painters who said ‘photography had nothing to do with art’.”(see announcement of the exhibition) Founded in 1943 by the American painter and art collector Elenore Lust in partnership with Jimmy Ernst (son of the painter Max Ernst) as a gallery for a cross section of contemporary painting, in 1947 Norlyst became an explicit photographic gallery exhibiting amateurs and professional photographers. Furthermore, the gallery supported the work of female artists: it was the place where Lotte Jacobi and Ruth Bernhard had their one-woman shows.

Flyer the exhibition “Captured Light” (© The Josef and Yaye Breitenbach Charitable Foundation, courtesy The Center for Creative Photography).

Announcement of the exhibition “Captured Light” (© The Josef and Yaye Breitenbach Charitable Foundation, courtesy The Center for Creative Photography)

Flyer of Lotte Jacobi’s exhibition at the Norlyst Gallery, 1948 (© 2020. University of New Hampshire).

Just around the corner of Norlyst, on 794 Lexington Avenue, you could find Weyhe Gallery. Opened in 1919 by the German-born art dealer Erhard Wehye, the bookstore and gallery space specialized on contemporary European artists. Similar to Norlyst gallery, Wehye supported the work of female photographers. In 1938, he showed works by Ruth Bernhard and in 1942 exhibited animal photographs by Ylla. Born as Camilla Koffler in Vienna in 1913, Ylla had her own studio for animal photographs in Paris, before she left for New York in 1940 with the support of the Museum of Modern Art.

Exhibition announcement “Animals” by Ylla. The New Yorker, 14 February 1942, pp. 11–12.

07Central Park Zoo/ East 64th Street

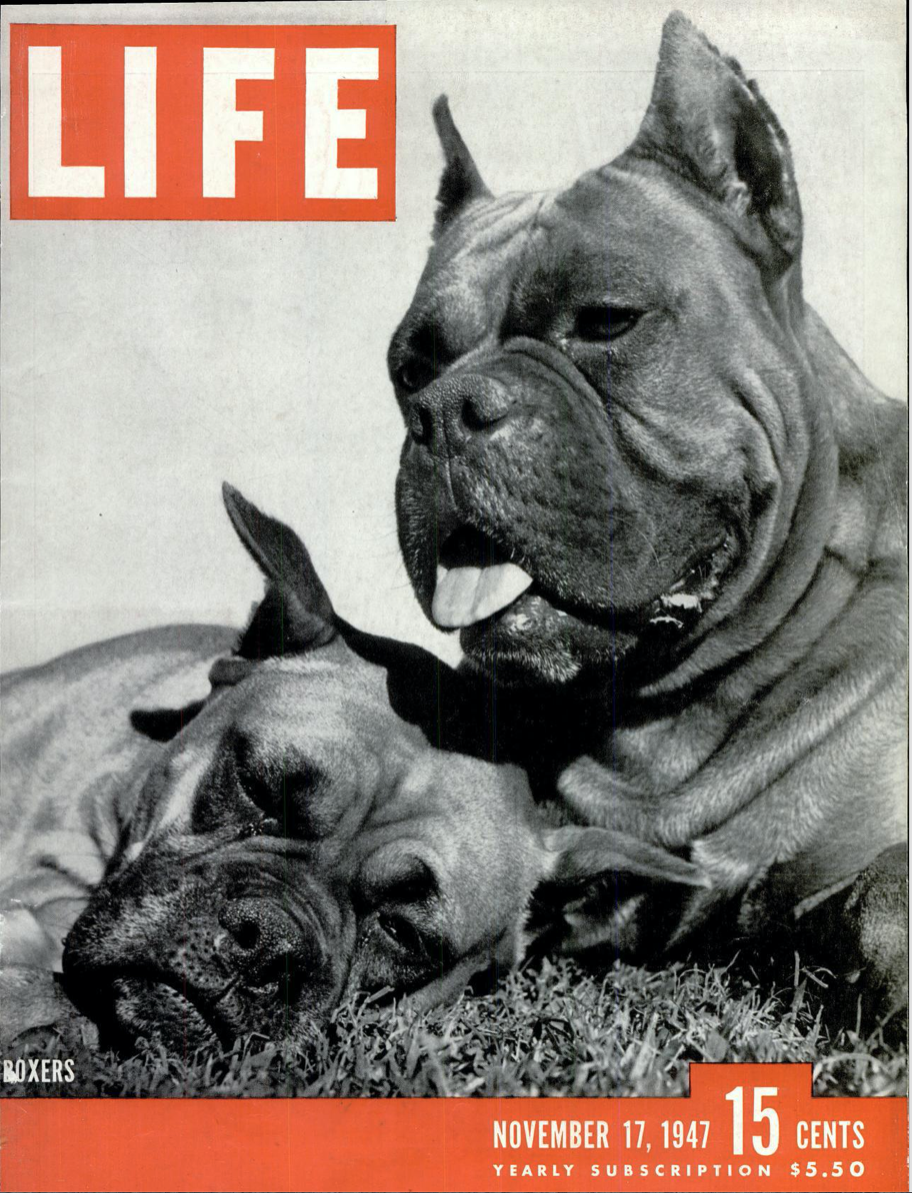

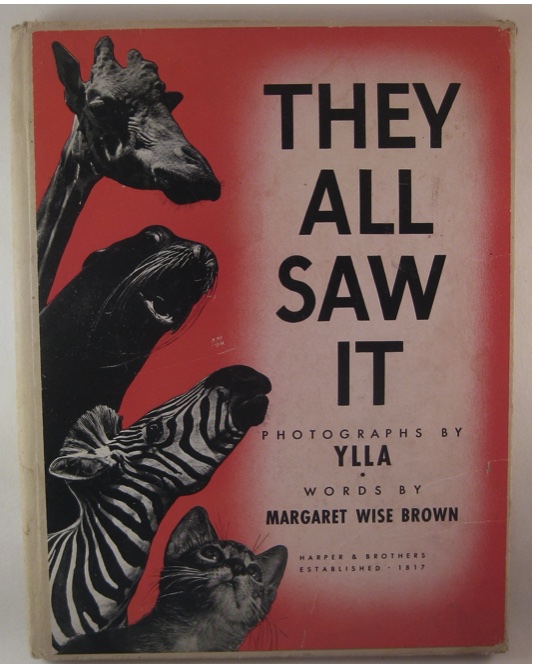

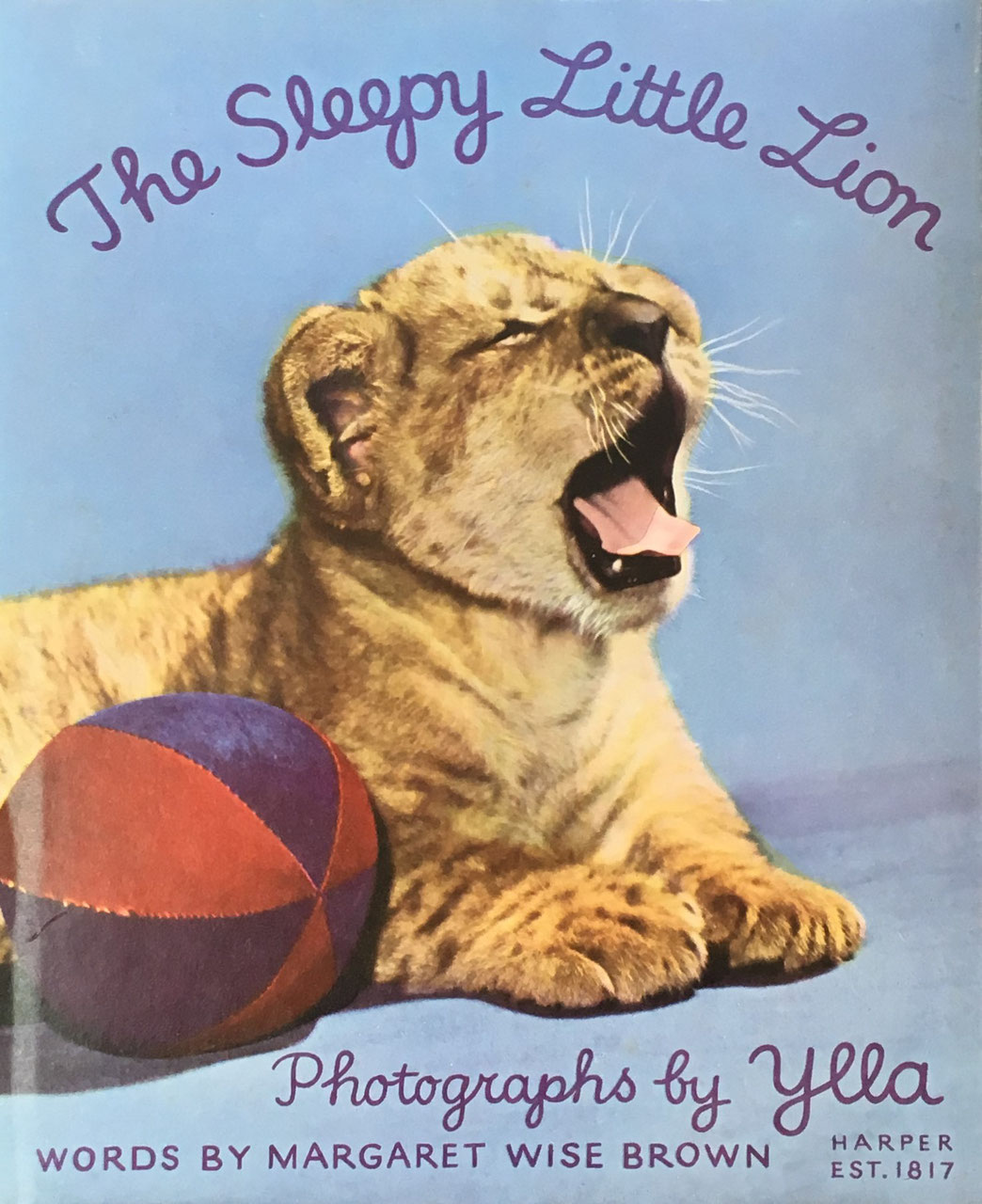

When Ylla did not take pictures of animals in her studio on 200 West 57th Street, among them a variety of dog portraits (Life, 17 November 1947), she went out to find models in the Central Park and Bronx Zoos. The Central Park Zoo, located on the east side of Manhattan’s green oasis, was only a short walk to her studio-apartment. For the article “Baby Time at the Zoo” (Life, 15 May 1944) she contributed five pictures taken at Bronx Zoo. Portraying animals is not easy, but the animals’ expressive and often funny poses clearly show her technical skills and her experienced handling of animals in front of her Rolleiflex camera. For her kitten series, she took the outside photos in Central Park (Popular Photography, 6 December 1951). Her work was represented by the photo agency Rapho Guillmette Pictures (59 East 54th Street); founded by the emigrant Charles Rapho in 1940. Besides magazine contributions, Ylla published quite a range of books beginning in Paris with Petits et Grands (1938) and then continuing in New York with They All Saw It (Harpers & Brothers, 1944), Dogs (Harpers & Brothers, 1945), The Sleepy Little Lion (Harpers & Brothers, 1947). Most of her books were translated into different languages.

Cover photo by Ylla for Life, 17 November 1947.

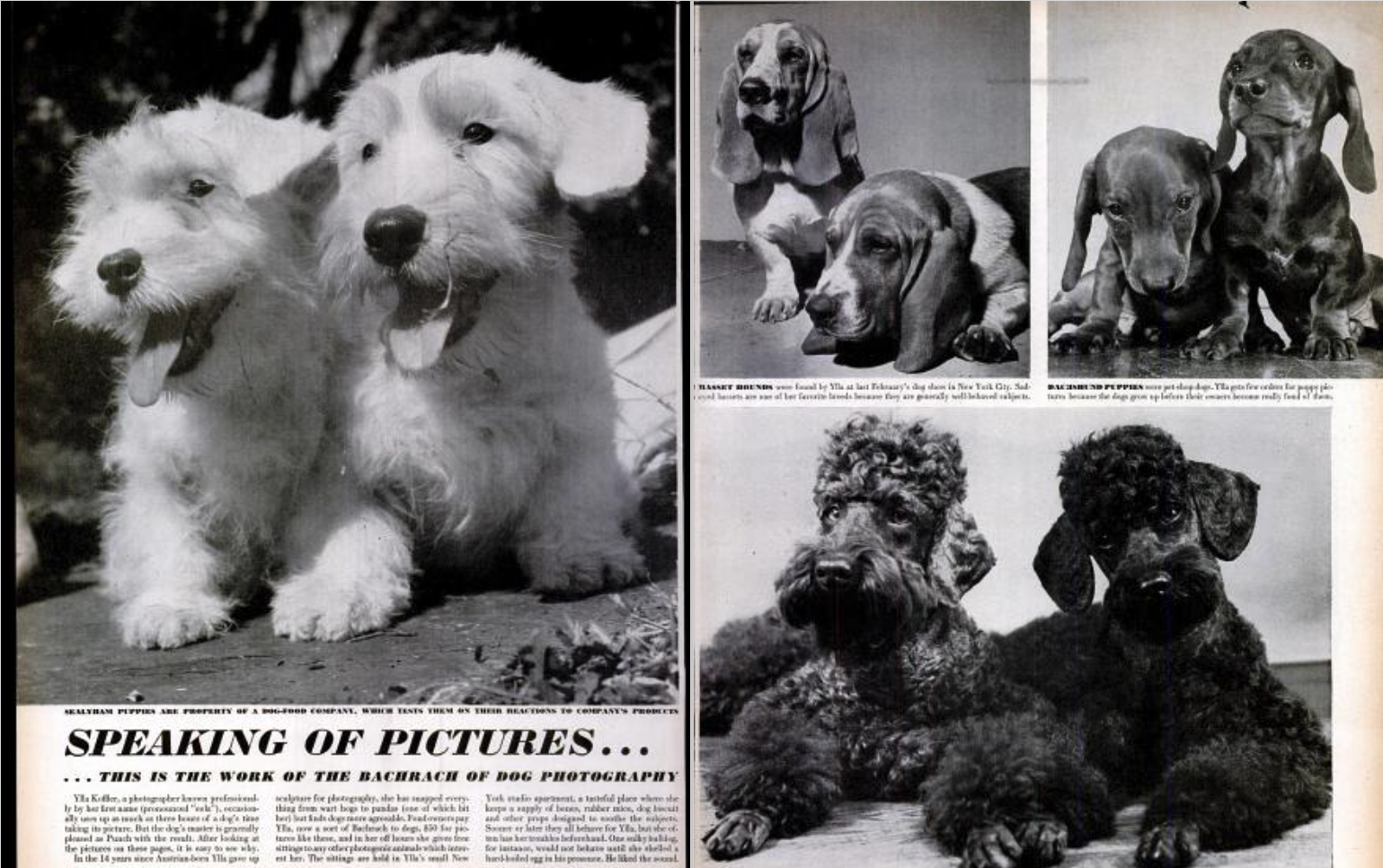

Images by Ylla for “Speaking of Pictures … this is the work of the Bachrach of Dog Photography.” Life, 17 November 1947, pp. 18–20.

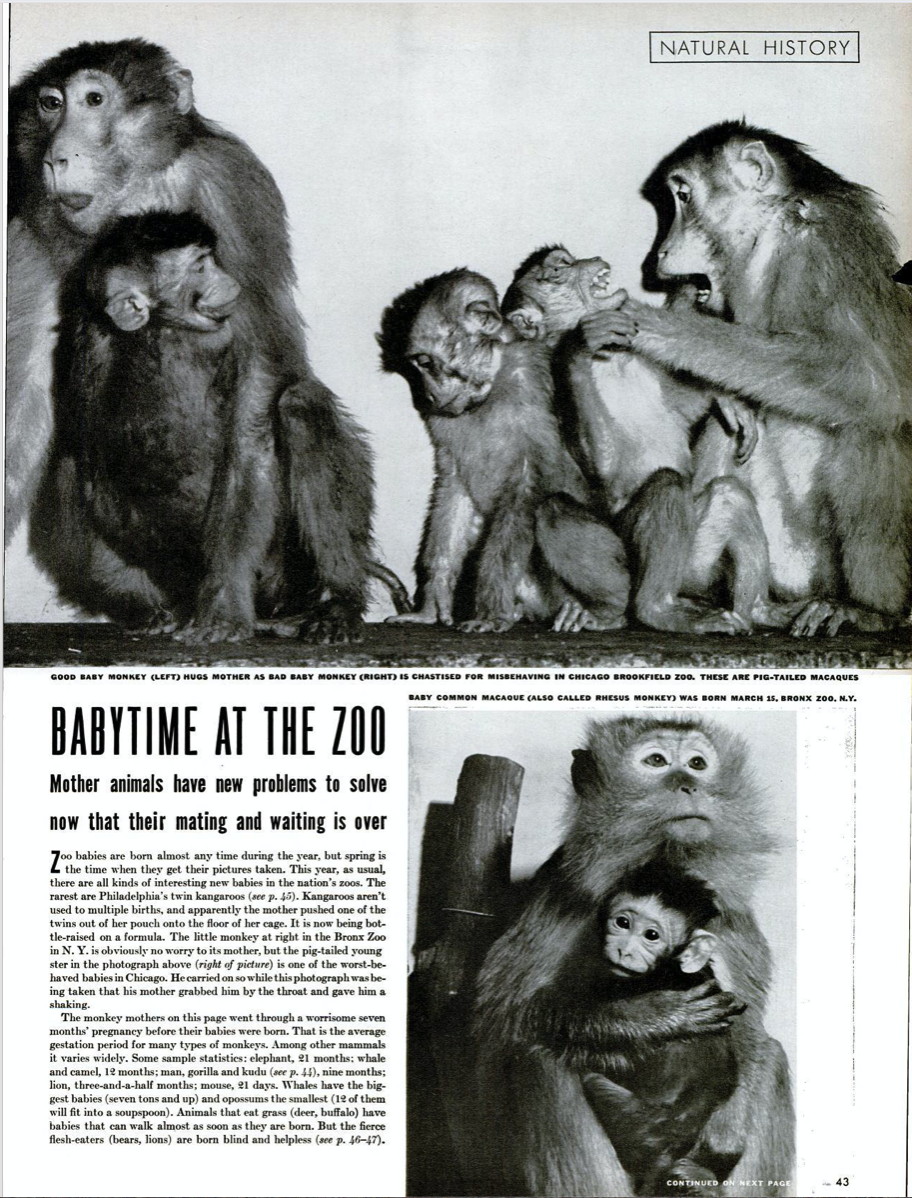

Images by Ylla for “Baby Time at the Zoo.” Life, 14 May 1944, p. 43.

Cover of Ylla’s photobook They All Saw It. Harpers & Brothers, 1944 (Private Archive: Helene Roth, 2020).

Cover of Ylla’s photobook The Sleepy Little Lion. Harpers & Brothers, 1947 (Private Archive: Helene Roth, 2020).

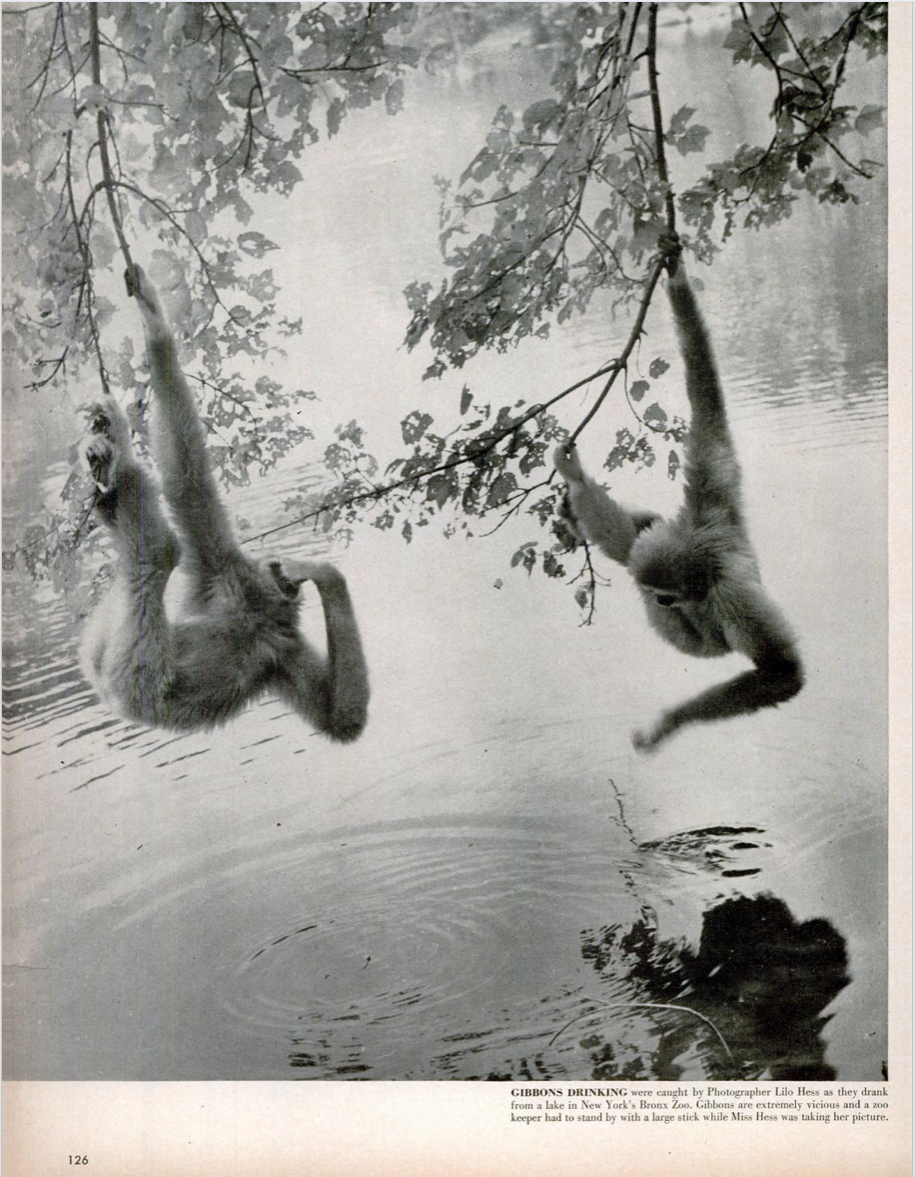

Ylla was not the only female émigré animal photographer in New York. German-born Lilo Hess came to New York in 1938, where she volunteered at the American Museum of Natural History. In the 1920s she had studied commercial photography at the Photographic School in Berlin and then started working as an animal photographer in London. She had a special assignment with the Bronx Zoo and some of her photographs were shown in Life. In 1951, she published her first children book Odd Pets (Crowell, 1951).

To reach our next stop, you can take a walk through Central Park, exiting on West 77th Street to have a look at the Natural History Museum on 200 Central Park West.

Photo of drinking gibbons at the Bronx Zoo, photographed by Lilo Hess (Life, 13 December 1948, p. 126).

Book cover of Odd Pets (Crowell, 1951) by Lilo Hess.

First page of the book Odd Pets (Crowell, 1951) by Lilo Hess.

Book page of the book Odd Pets (Crowell, 1951) by Lilo Hess.

The Central Park was an attractive location for outside shootings. Commissioned by the Black Star Agency, the German-émigré photographer Lilly Joss-Reich photographed the series “Frühling im Central Park” [Spring in Central Park] in 1944. (© Wien Museum / kunstdokumentation.com).

Further image by Lilly Joss Reich for her series “Frühling im Central Park” [Spring in Central Park] in 1944. (© Wien Museum / kunstdokumentation.com). / kunstdokumentation.com).

08Fred Stein Apartment/ 610 West 145th Street

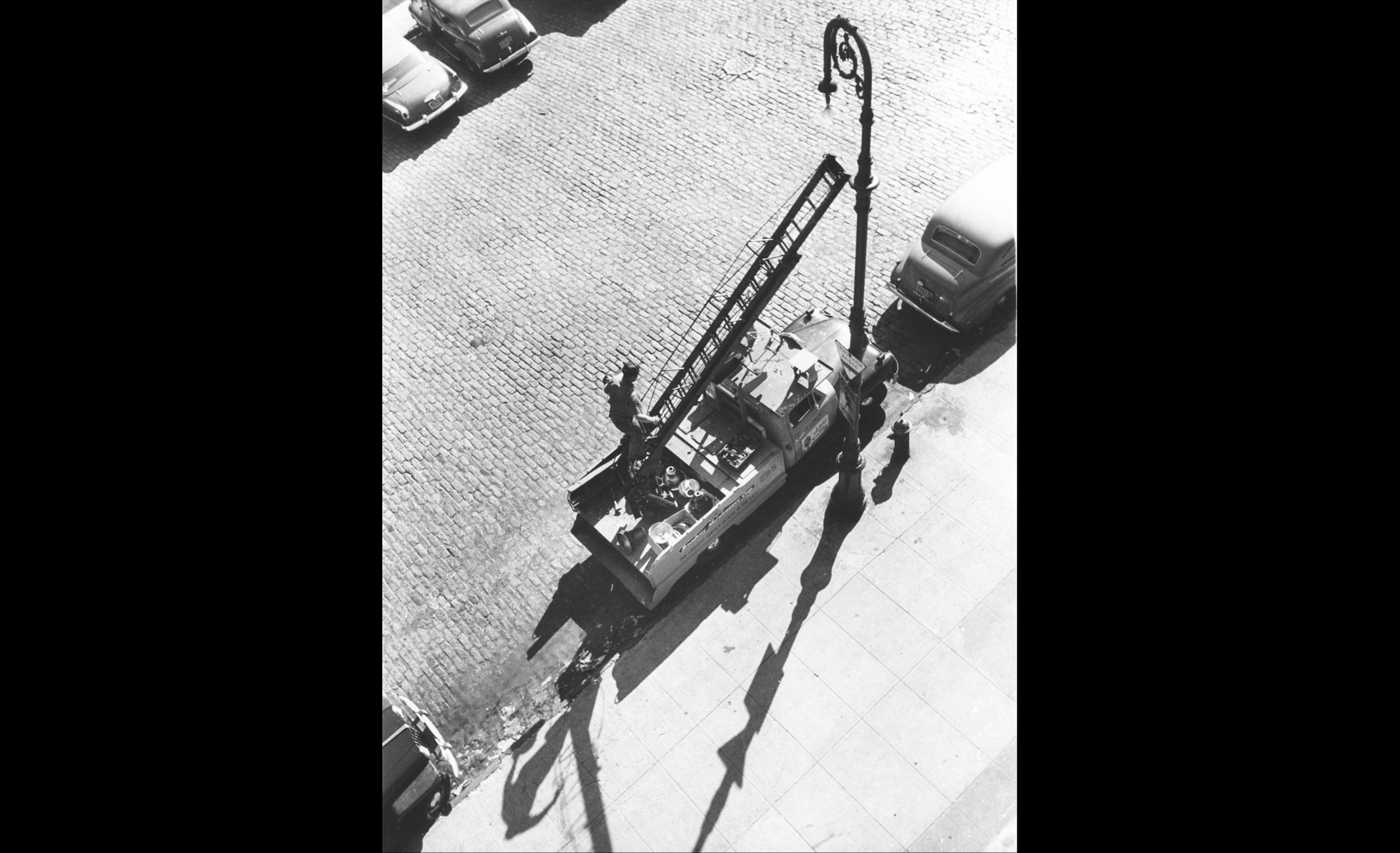

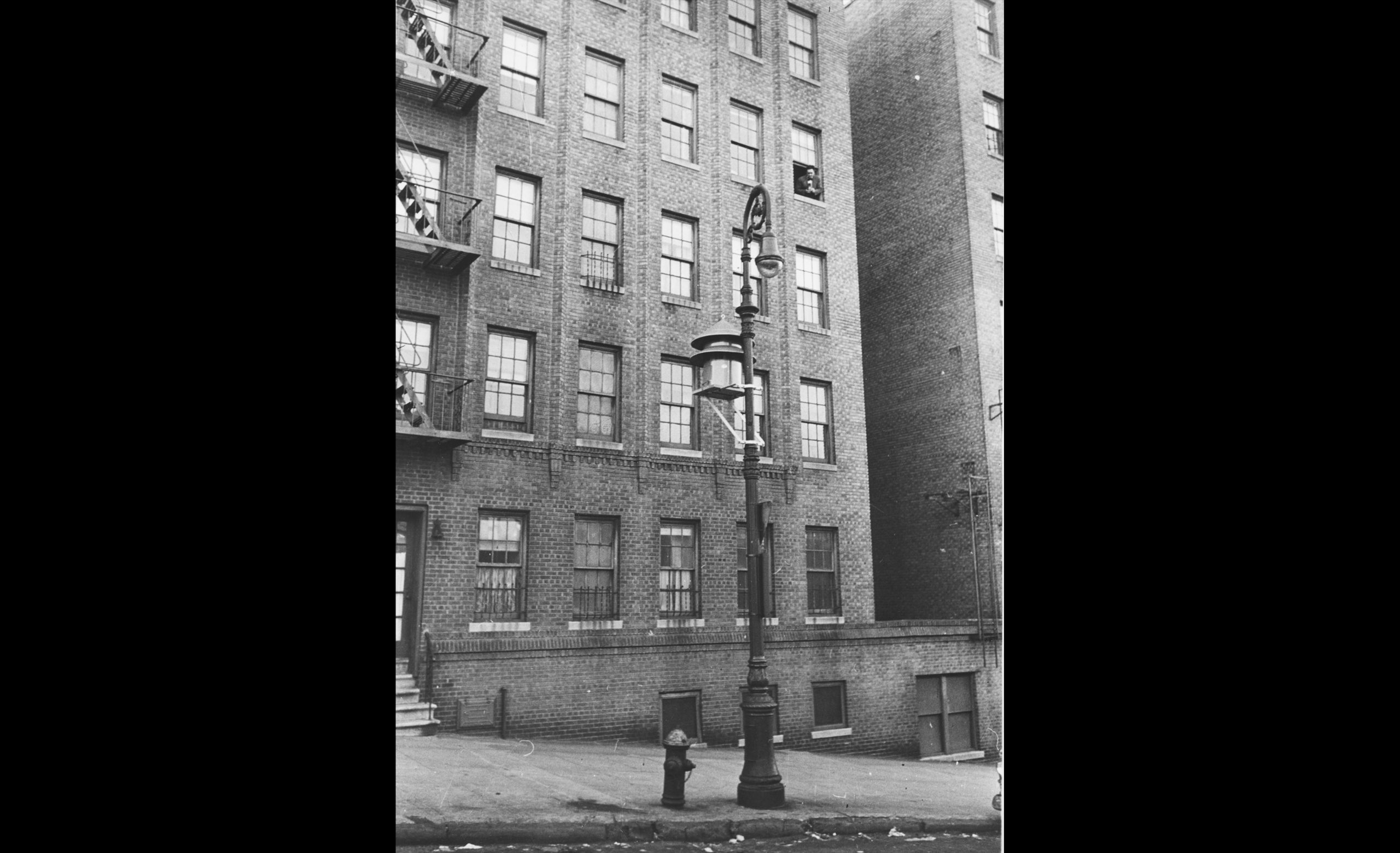

Fred Stein ran his own photo studio in Paris before emigrating to New York in 1941 with his wife and son. Between 1941 and 1951, Stein took a series of 18 pictures from his apartment window focusing on a lamppost on the street. The position from where he took his photos can be deduced from the first picture in the series. It was perhaps captured by his wife who stood on the street focusing on the lamppost and, in the back, upwards on her husband in the window. The daytimes and seasons as well as the urban life in the city and rush hour can be vividly reconstructed by the impeccably constructed photographs. Stein chose his point of view in a precise way and turned his camera to the left, so that the pavement divided the picture diagonally and made the lantern appear mostly frontal, like a portrait. He skilfully composed the play of light and shadow. It becomes clear here that everyday street scenes of the vivid life in the metropolis nourished Stein’s artistic project.

According to Peter Stein, Fred Stein’s son, towards the end of his series the city installed sirens on the lamppost. These modifications can be reconstructed in the pictures and were tested every day at noon. They were to be used in case the Russians attacked the United States; there were also air raid shelters the city’s population was supposed to seek out.

Image of series of lamppost from Fred Stein’s apartment window, 1941–1951 (© Estate Fred Stein).

Further image series of lamppost from Fred Stein’s apartment window, with him in the window 1941–1951 (© Estate Fred Stein).

09“German Yorkville”:/ East 86th Street

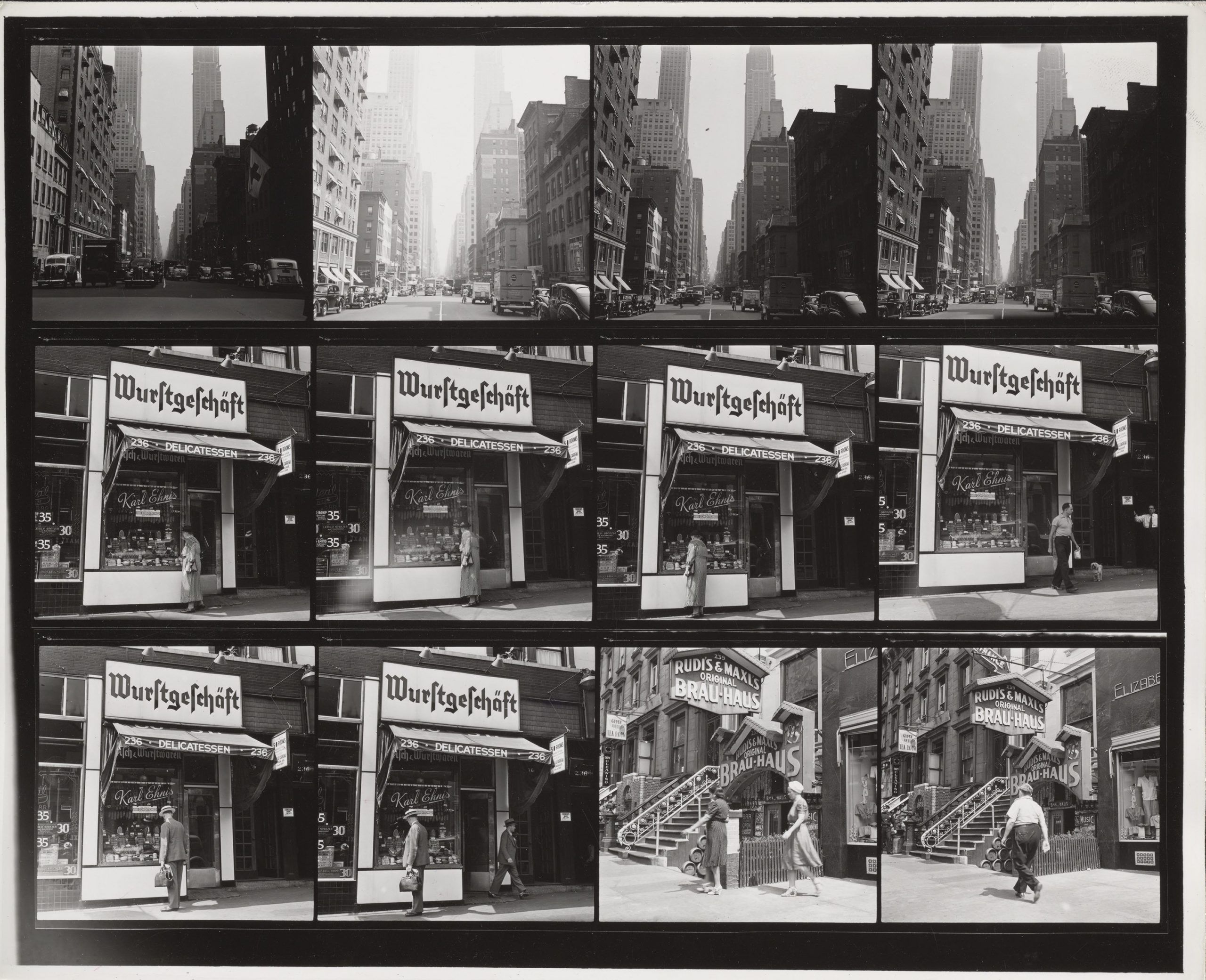

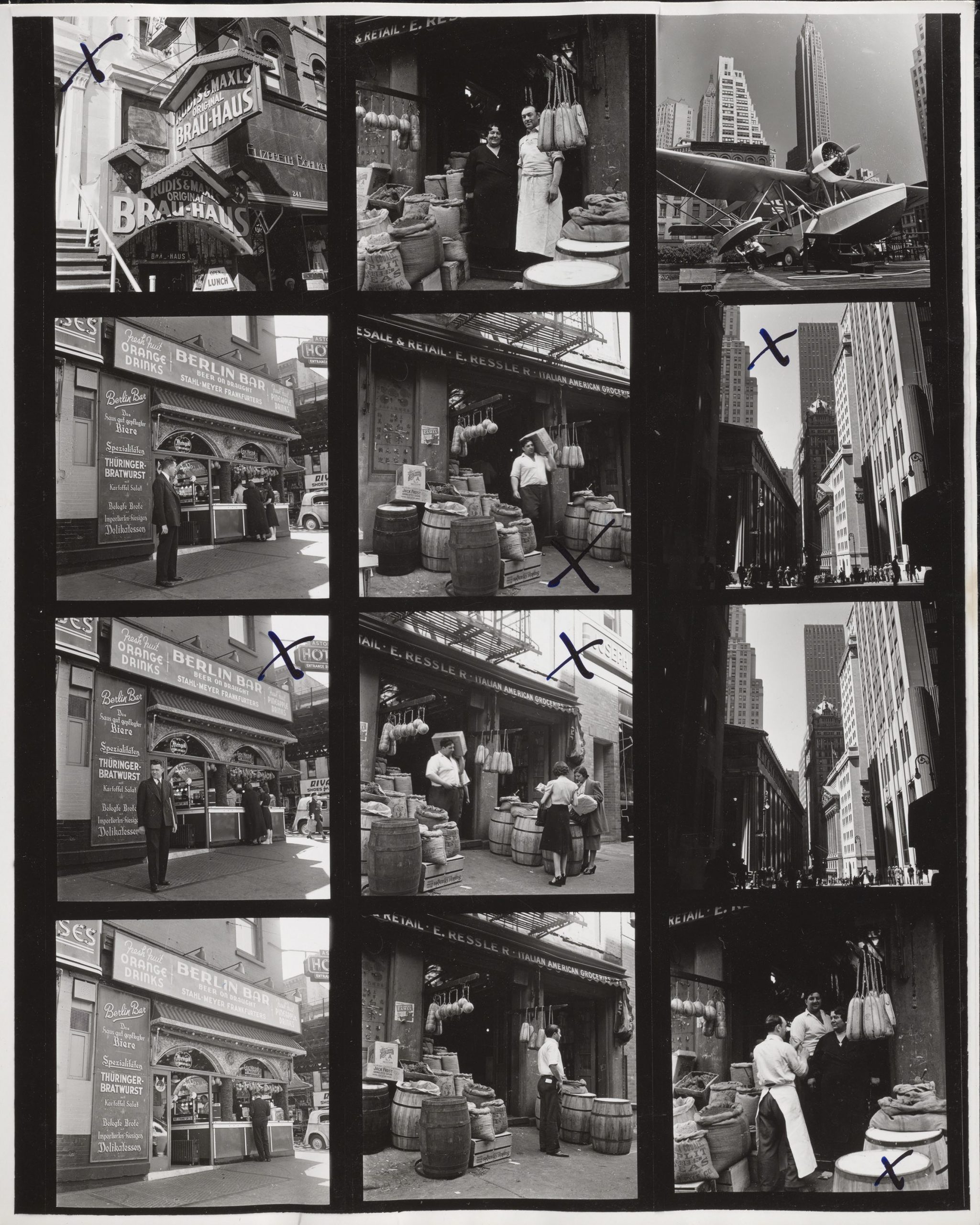

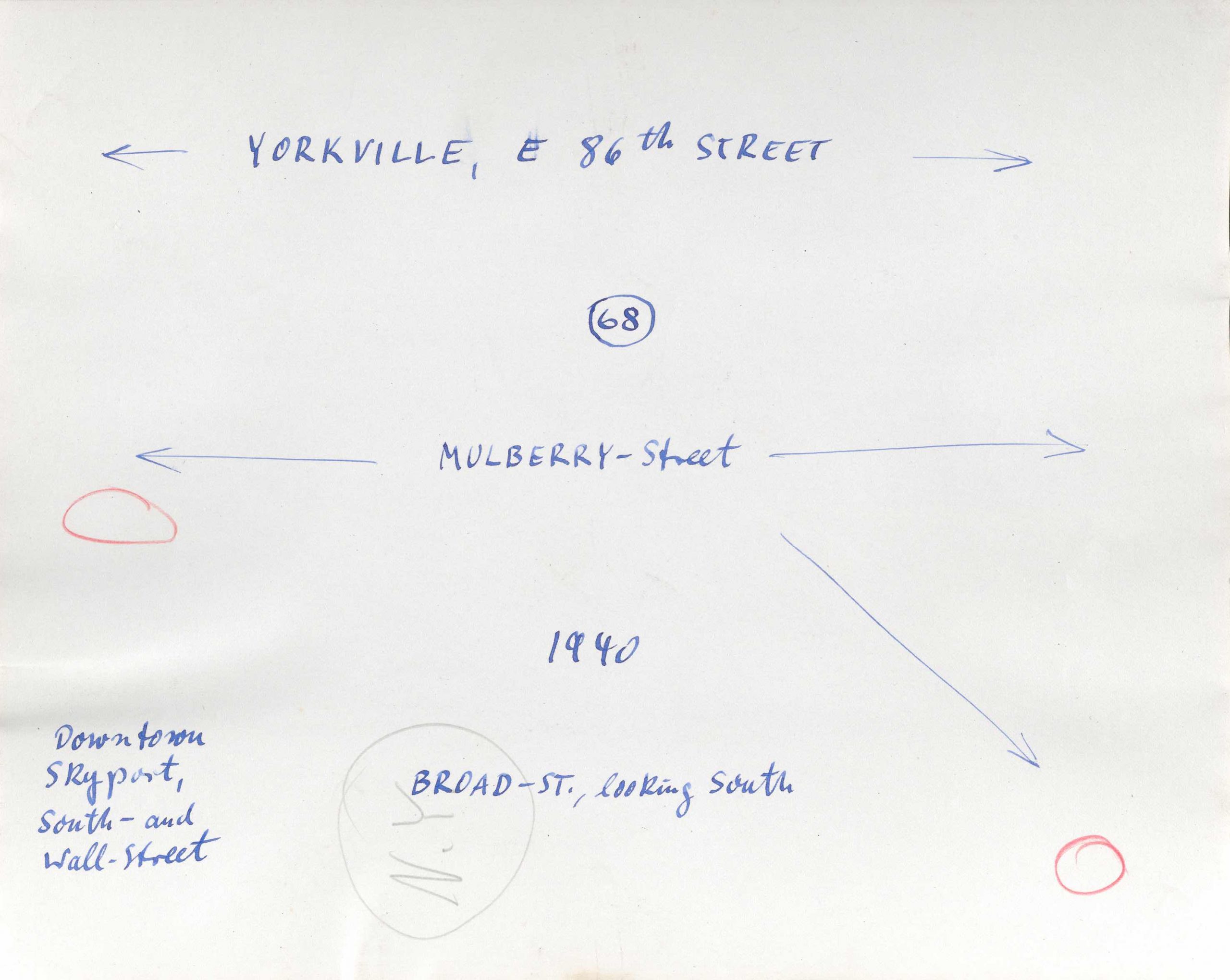

The article “Kleiner Gesundheitsführer” [“Little Health Guide”] in Almanac. The Immigrant’s Handbook by Aufbau Magazine, advises a balanced diet of dark and grainy bread (Vollkornbrot). It indicates that some types of sausage, such as tea sausage spread (Teewurst), and cold cuts could contain uncooked pork and transmit parasitic infectious diseases due to insufficient testing. This reference to European foods shows that they were also available in New York. Especially the German Christian Community in Yorkville self-produced food and, until the outbreak of the war, directly imported from Germany. Around the corner of 86th Street you could find an array of German and Austrian food establishments and a blossoming cultural scene. On a walking tour through Yorkville (which can be re-traced with the help of his contact sheets), Andreas Feininger photographed shop windows with German signs such as the “Wurstgeschäft” (236 East 86th St.), owned by the emigrant butcher Karl Ehnis, the Bavarian brewing house “Rudi’s and Maxl’s Brau Haus” (239 East 86th St.) or the “Berlin Bar”(200 East 86th).

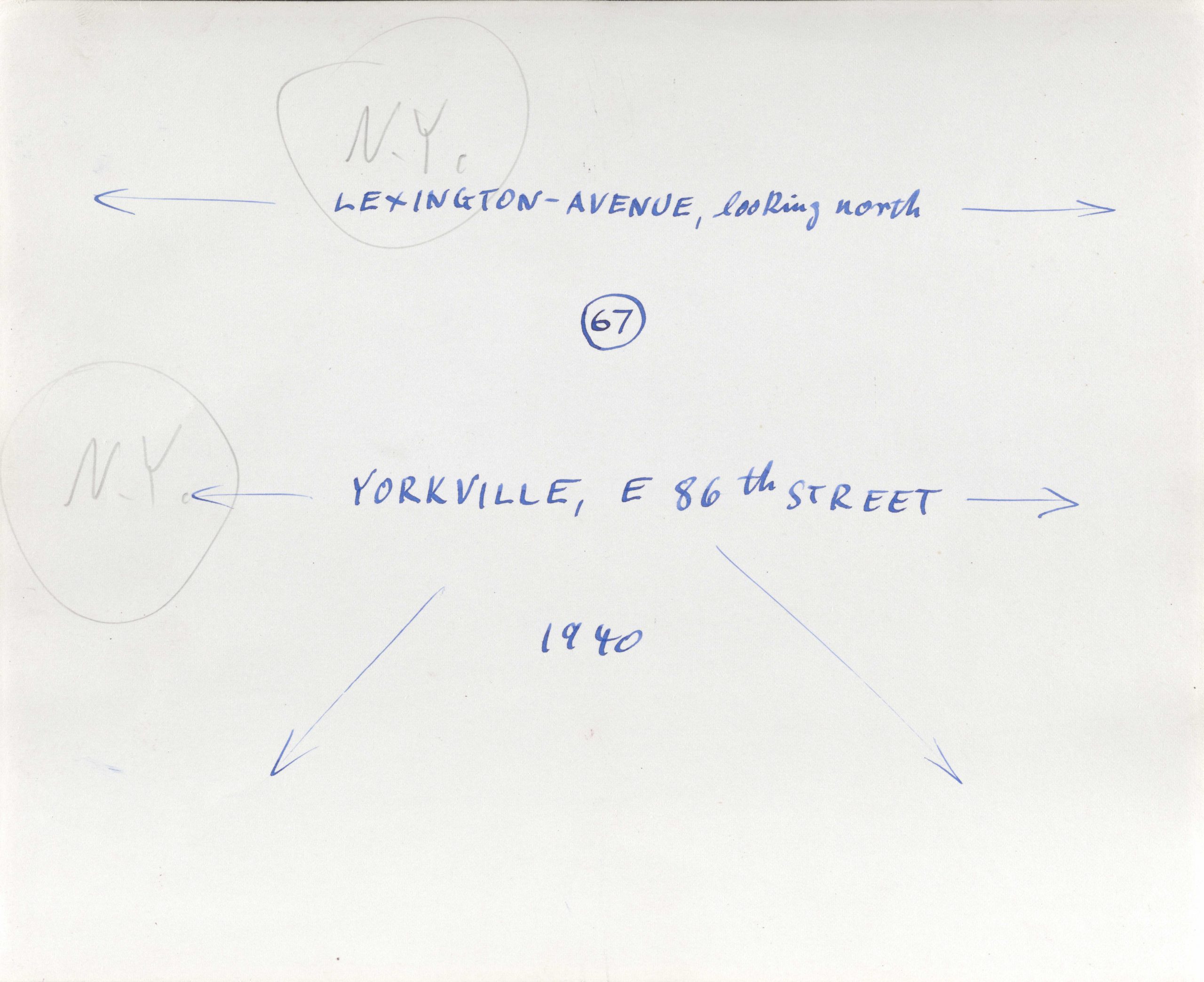

Contact sheet by Andreas Feininger showing different German shop windows in Yorkville as the “Wurstgeschäft” and “Rudi’s and Maxl’s Brau Haus” (© Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona).

Backside of the contact sheet with indication of the adresse, where Andreas Feininger made the pictures (© Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona).

Contact sheet by Andreas Feininger with images by the “Berlin Bar” (© Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona).

Backside of the contact sheet with indication of the adresse, where Andreas Feininger made the pictures (© Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona).

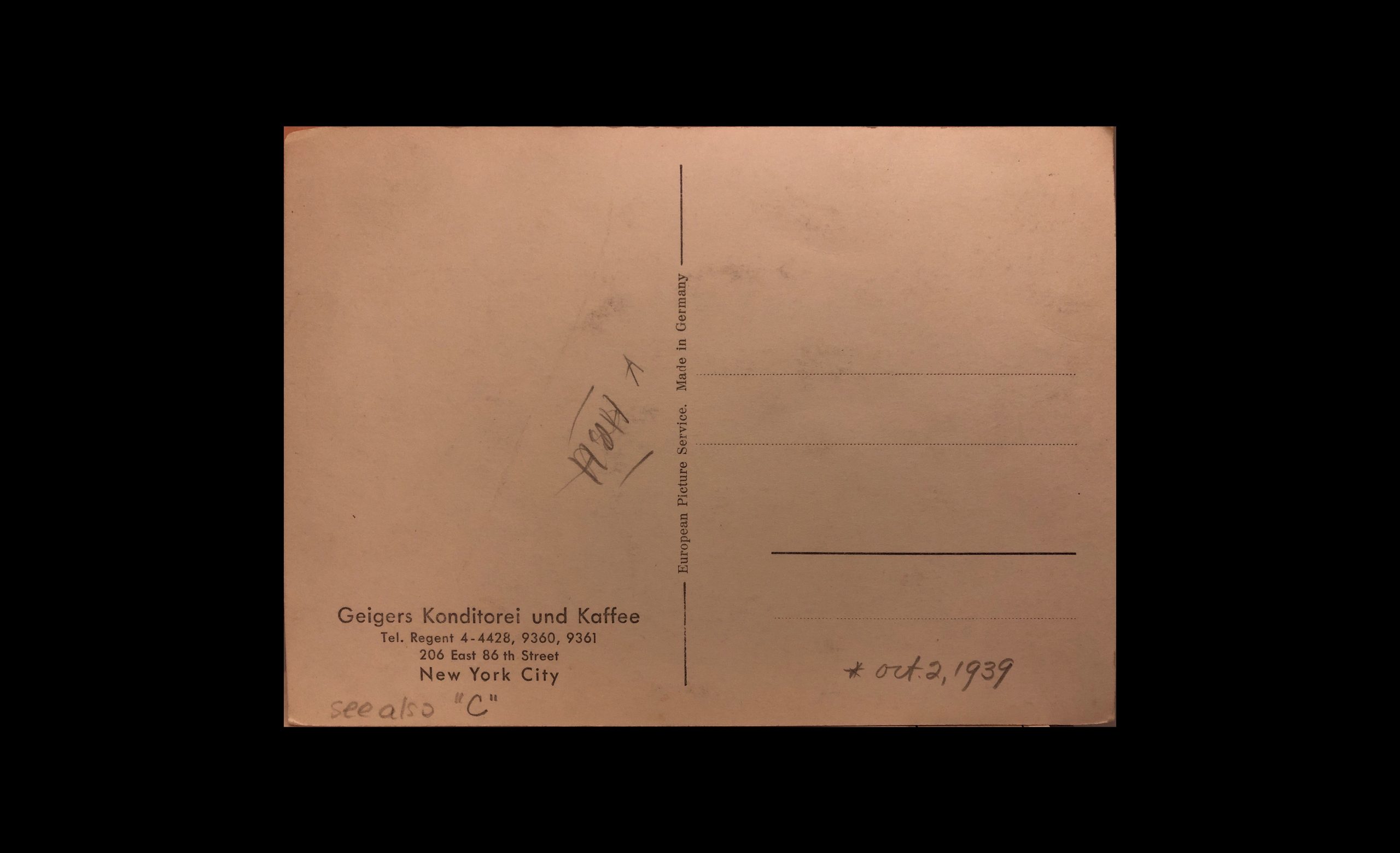

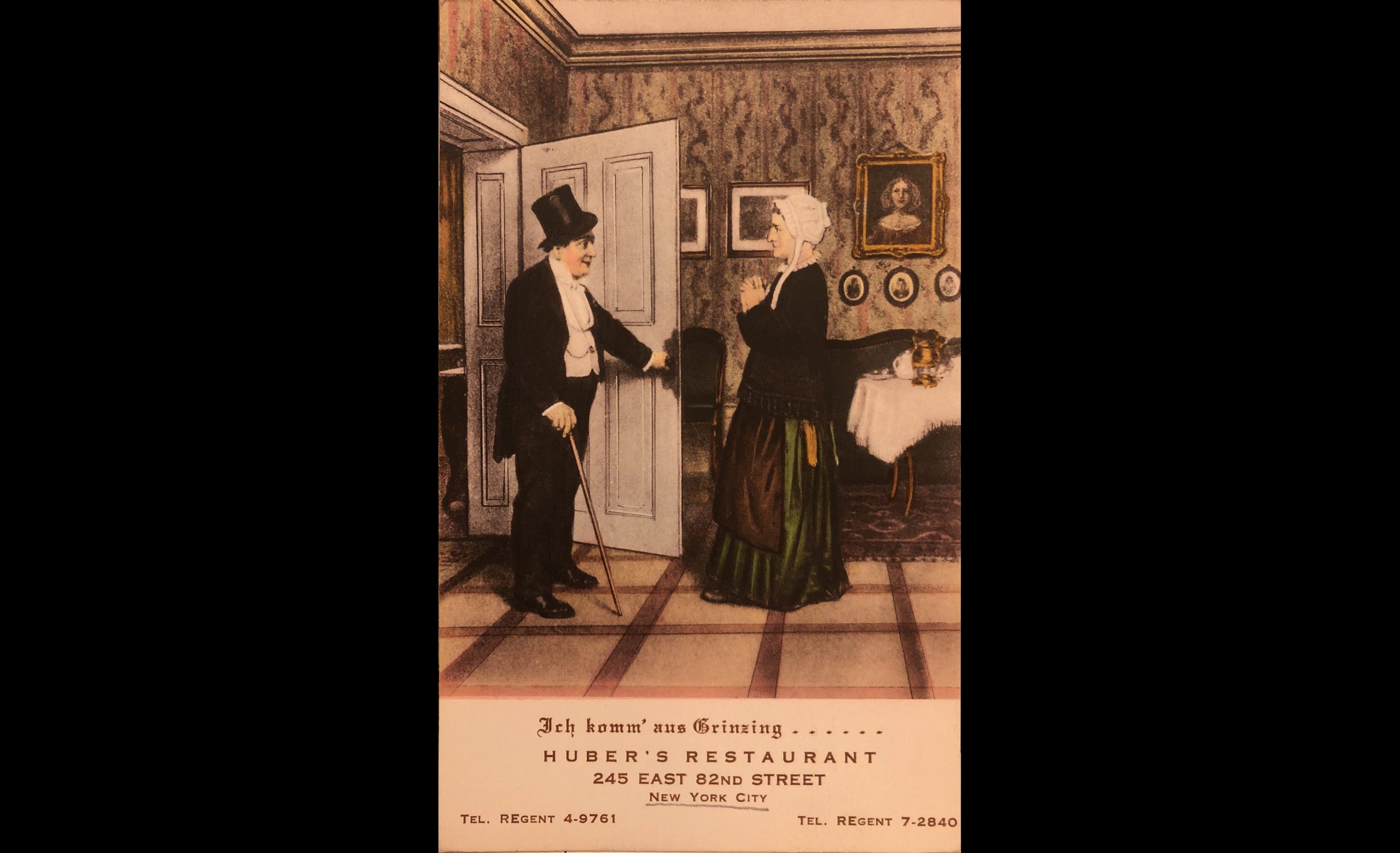

Some other remnants of this cultural environment can be found when looking at postcards displaying restaurants and cabarets: “Geiger’s Konditorei und Kaffee” (206 East 86th St.), “Rheinland Restaurant und Cabaret” (228 East 86th St.) or “Huber’s Restaurant” (245 East 82nd St.), which were all located in the same street or area. Because of the high number of German restaurants and shops, the eastern section of 86th Street was once called “German Broadway” or “German Yorkville”.

Postcard of the German pastry shop “Geigers Konditorei und Kaffee” restaurants and cabarets (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

Backside of the postcards of the German pastry shop “Geigers Konditorei und Kaffee” restaurants and cabarets (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

Postcard of the German “Huber’s Restaurant” (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

Postcard of the German “Rheinland Cabaret and Restaurant” (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

Even now, you can still find a few remaining German businesses on the Upper East Side, like the butchery “Schaller & Weber” and the restaurant “Heidelberg” on the corner of 2nd Avenue to 86th Street. In a video about the butchery you can learn more on the history of Anton Schaller and his sons who came to New York in the late 1920s and opened their store in 1937. Directly next to the butchery, there is a restaurant called “Heidelberg”, which opened in 1936 and which still serves homemade German dishes, purchasing its sausages from “Schaller & Weber” next door. The furniture and design are traditionally German, and the waiters and waitresses wear typical German clothes, such as Lederhosen and Dirndl dresses.

Today’s storefront of “Schallers & Weber” (Photo: Helene Roth, 2019).

Today’s inside view of “Schallers & Weber”(Photo: Helene Roth, 2019).

You can even buy a traditional Leberkase sandwich (Photo: Helene Roth, 2019).

Today’s storefront of “Heidelberg Restaurant” (Photo: Helene Roth, 2019).

10Unisphere/ Avenue of the Americans, Flushing-Meadows-Park

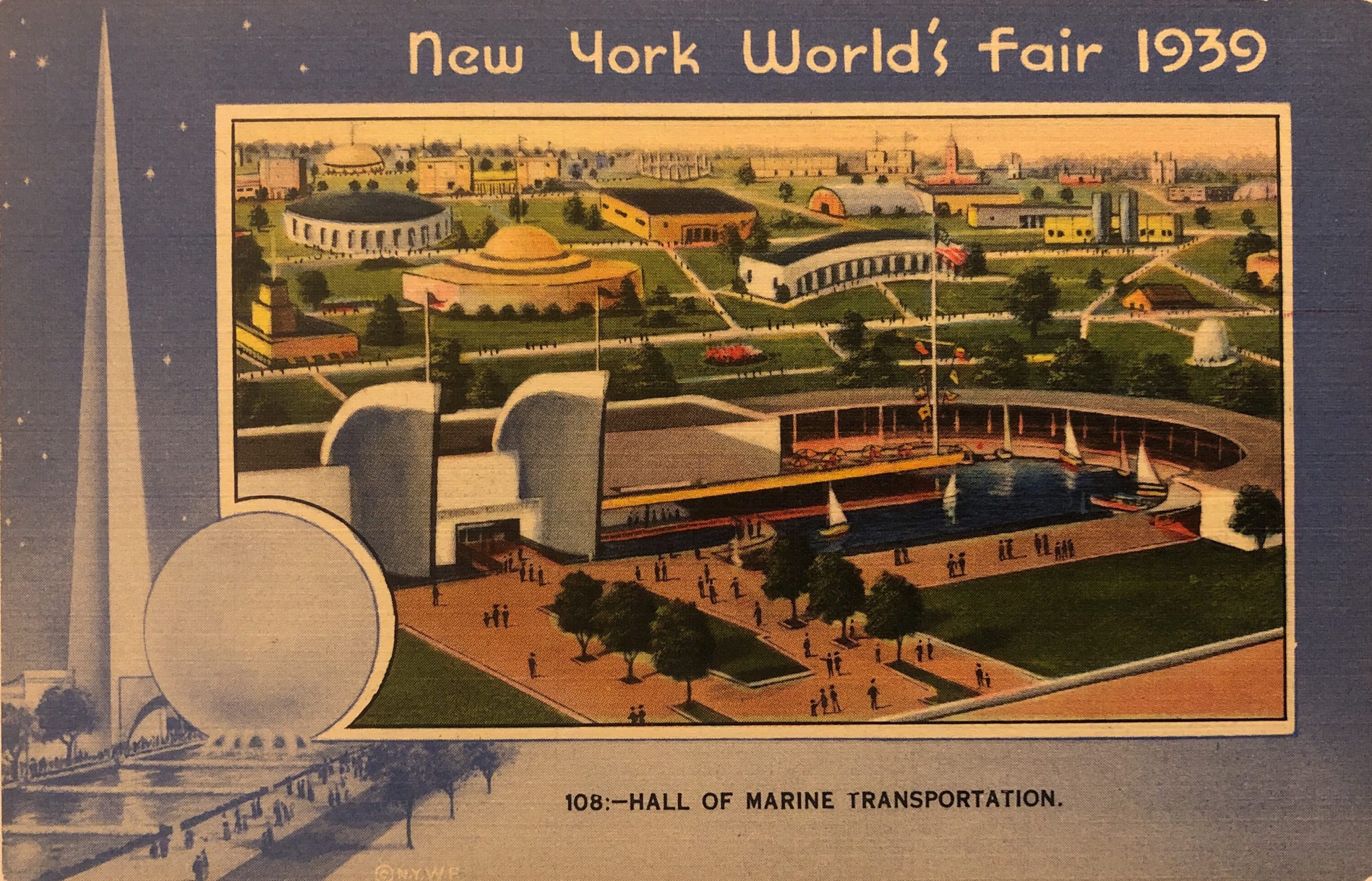

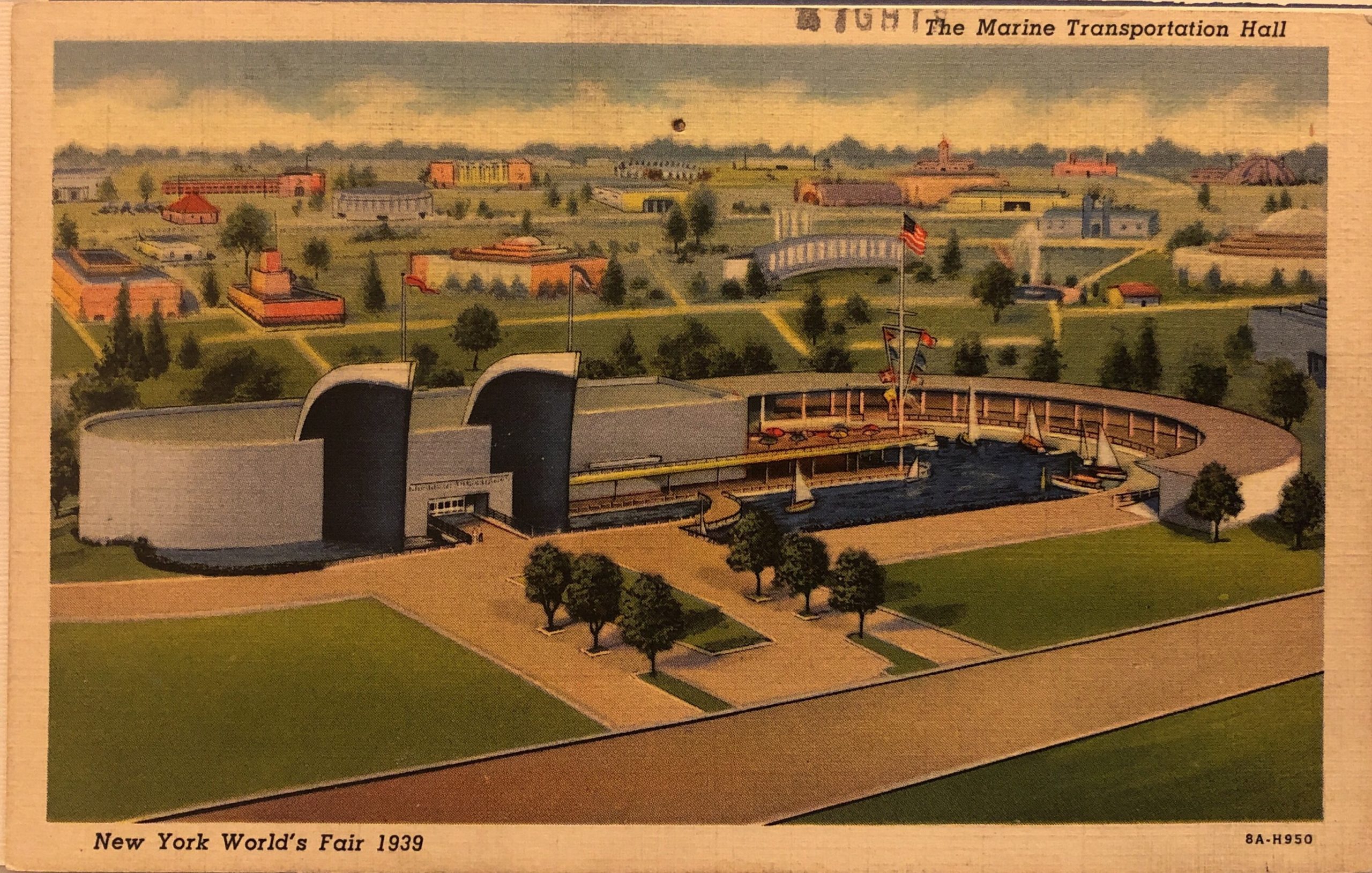

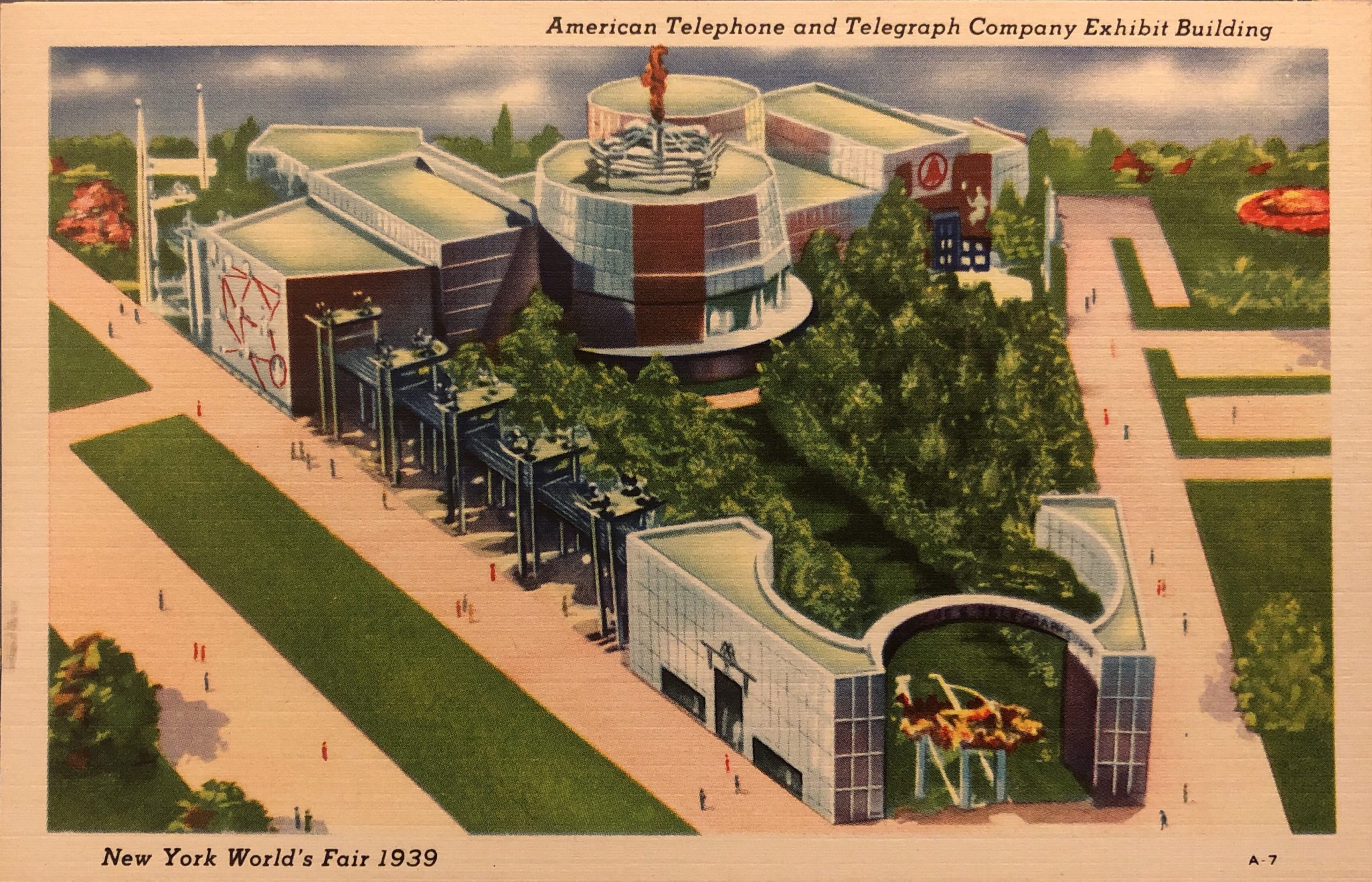

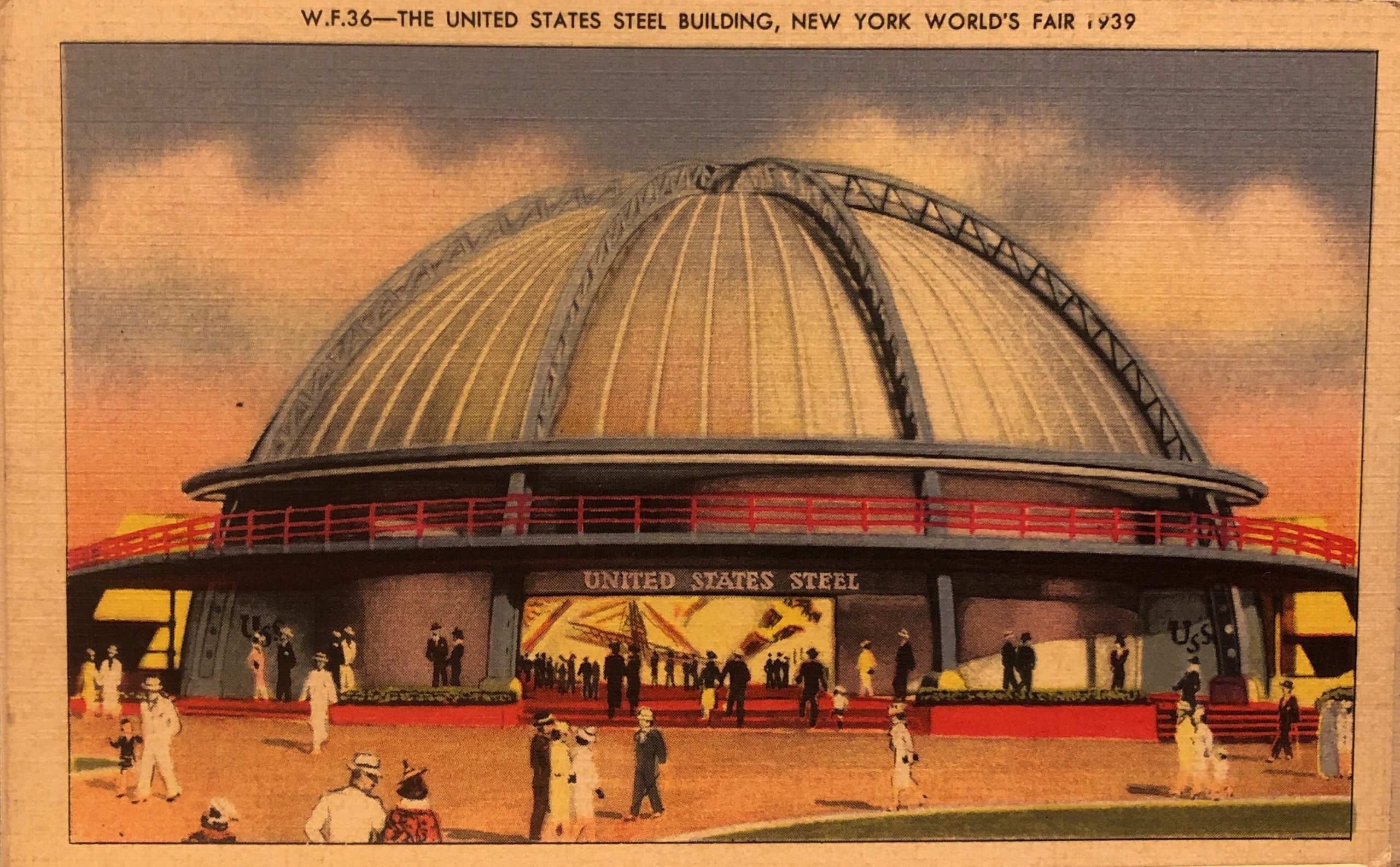

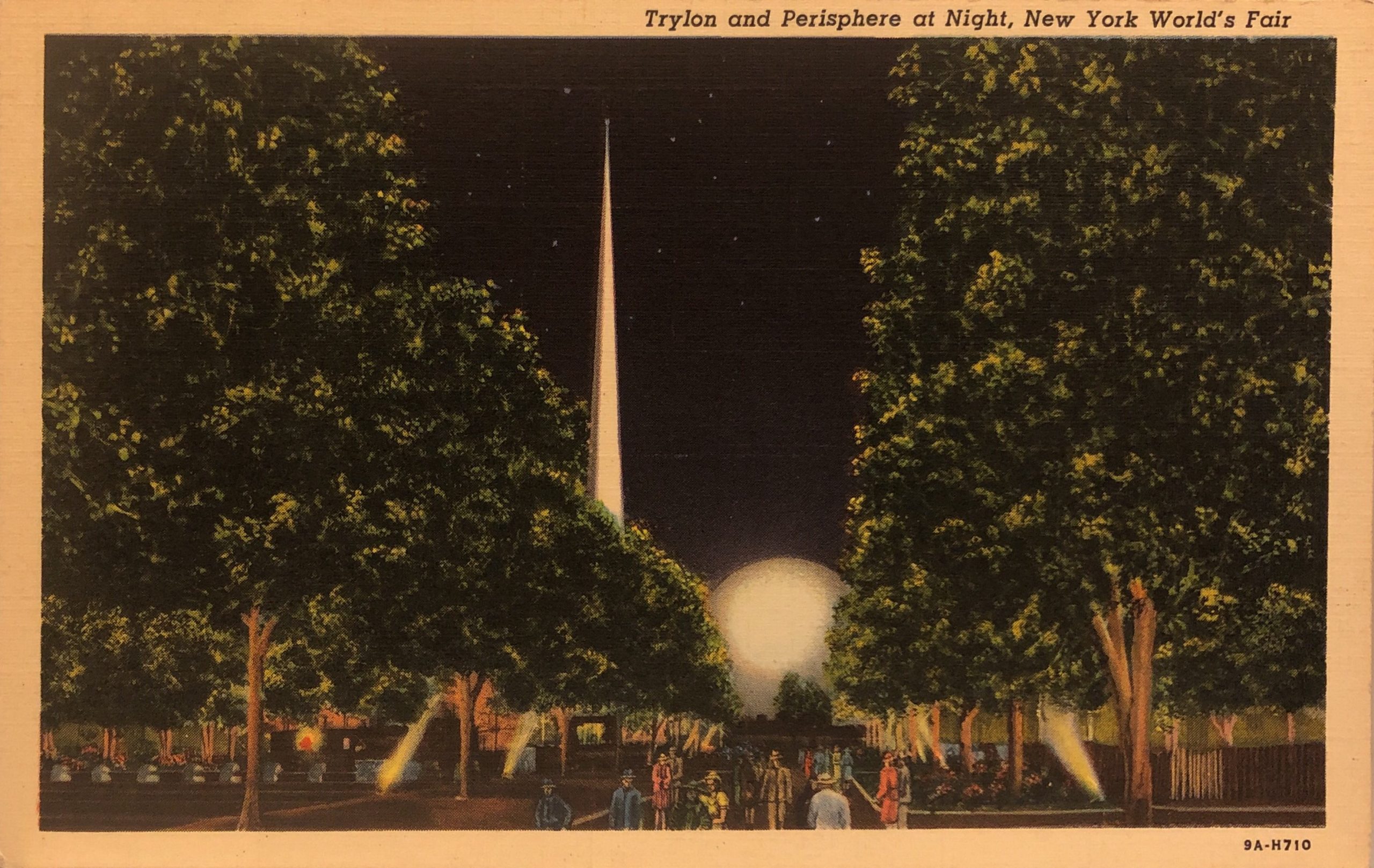

After the Great Depression, the slogan of the 1939 World’s Fair at Flushing Meadows, “Building the World of Tomorrow with the Tools of Today,” tried to articulate new technical and industrial achievements which are expressed in futuristic and geometric architectural forms. Numerous émigrés, such as the Swiss-born architect William Lescaze (Swiss Pavilion and Aviation Building) or Lyonel Feininger’s mural for the Marine Transportation Building, Alexander Calder’s Water Balett (Consolidated Edison Company building), as well many other artists and intellectuals, were involved in the World’s Fair. As Nazi-Germany did not participate with a pavilion, the contribution of emigrants had an additional social and political message. On April 30 1939, one hundred and fifty years after the inauguration of George Washington, the first president of the United States, the New York World’s Fair opened its doors on the grounds of the Flushing Meadows Corona Park. Because the city expected a large number of visitors and tourists, numerous city guides, travelogues, illustrated books and a range of commercial publishing media were produced.

Postcards of the New York World’s Fair 1939 (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

Postcards of the Marine Transportation Hall at the New York World’s Fair 1939 (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

Postcards of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company Exhibit Building at the New York World’s Fair 1939 (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

Postcards of the United States Steel Building at the New York World’s Fair 1939 (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

Postcards of the Trylon and Perisphere at Night at the New York World’s Fair 1939 (© Collection of the New-York Historical Society).

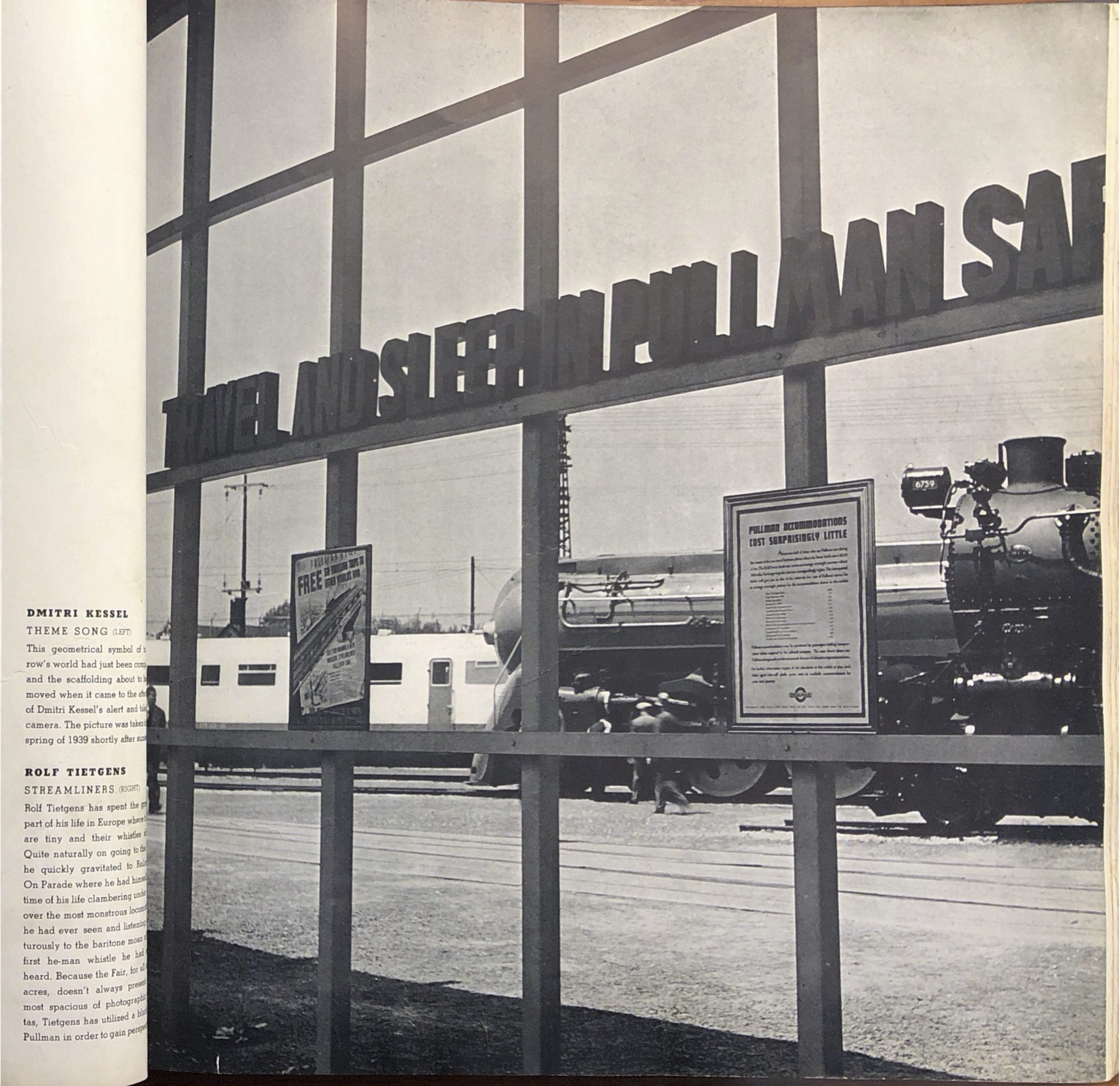

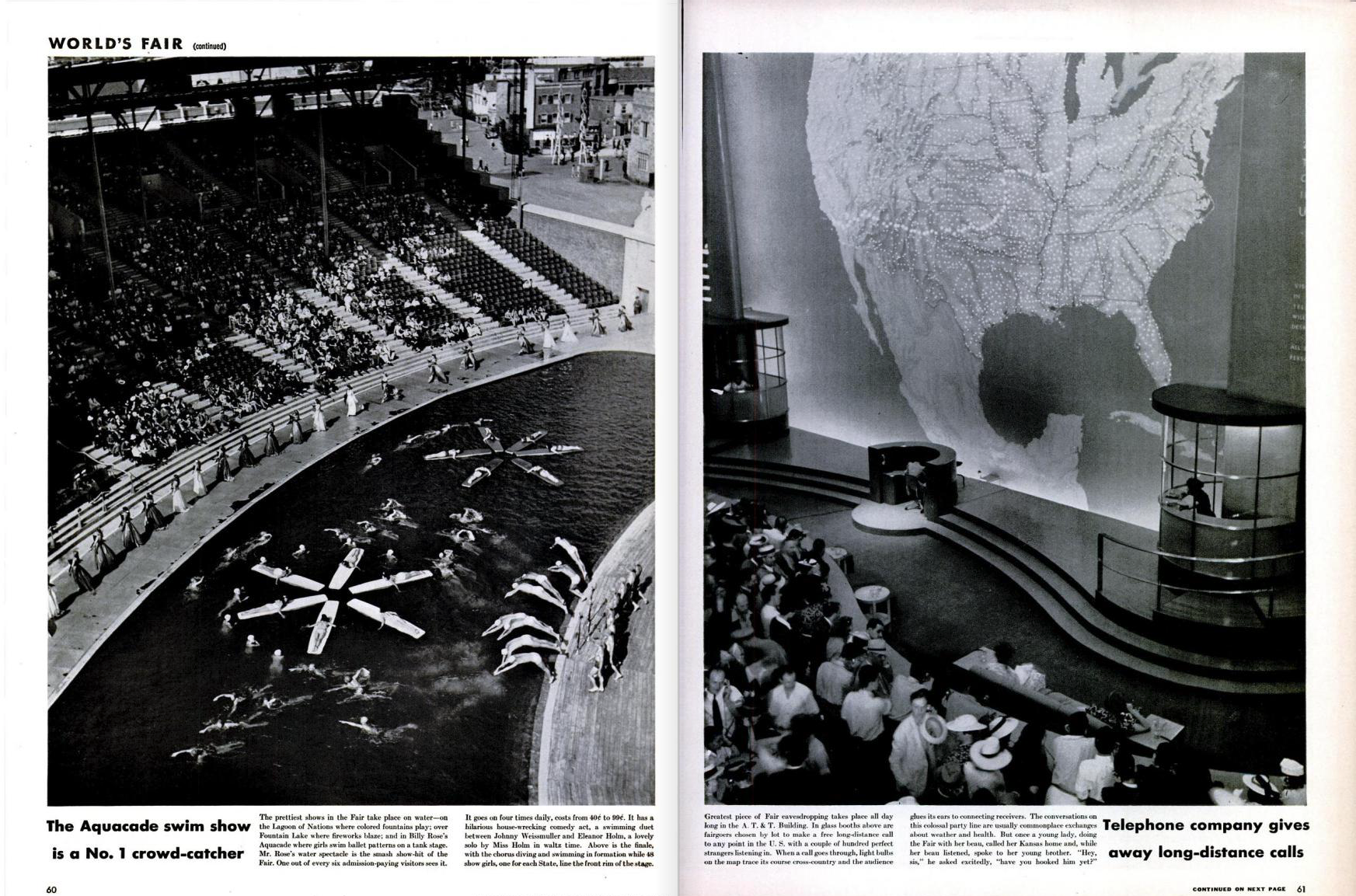

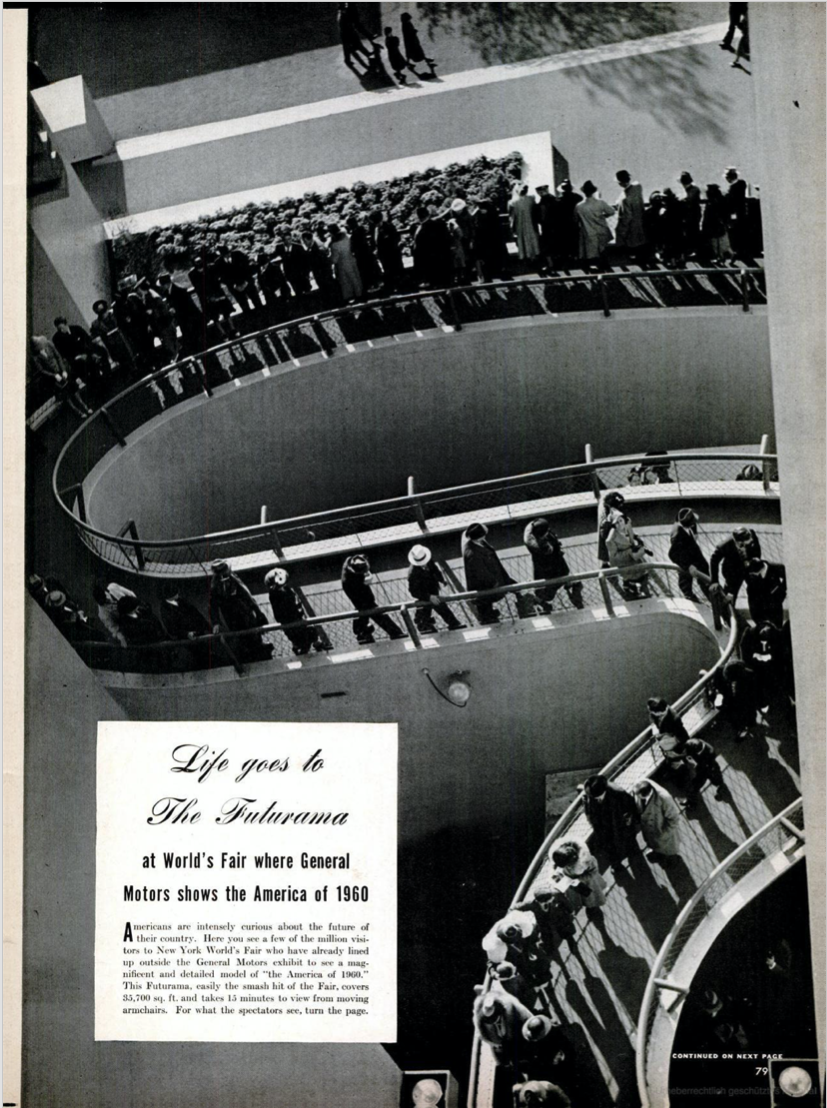

Many photographers – among them émigrés – captured the atmosphere, the pavilions and the architecture of this event. Heavily Influenced by the aesthetics of New Objectivity in Germany, the geometric and futuristic forms of the World’s Fair as well as the parades opened the way to experiment with artistic images. This becomes evident in photographs by the German émigrés Rolf Tietgens or Walter Sanders which were published in a special issue of the U.S. Camera and Life. The photographer Andreas Feininger was especially attracted by the fluorescent night-time lights and created experimental photographs showing highly illuminated buildings.

Photo by Rolf Tietgens in U.S. Camera World’s Fair Issue, no. 5, August 1939, p. 38.

Photo by Rolf Tietgens in U.S. Camera World’s Fair Issue, no. 5, August 1939, p. 45.

Photo of the Aquade swim show by Walter Sanders for Black Star and reproduction in Life, 3 July 1939, pp. 60–61.

“Lifes goes to the Futurama” with an image of the General Motors Show by Walter Sanders in Life, 5 June 1939, p. 79.

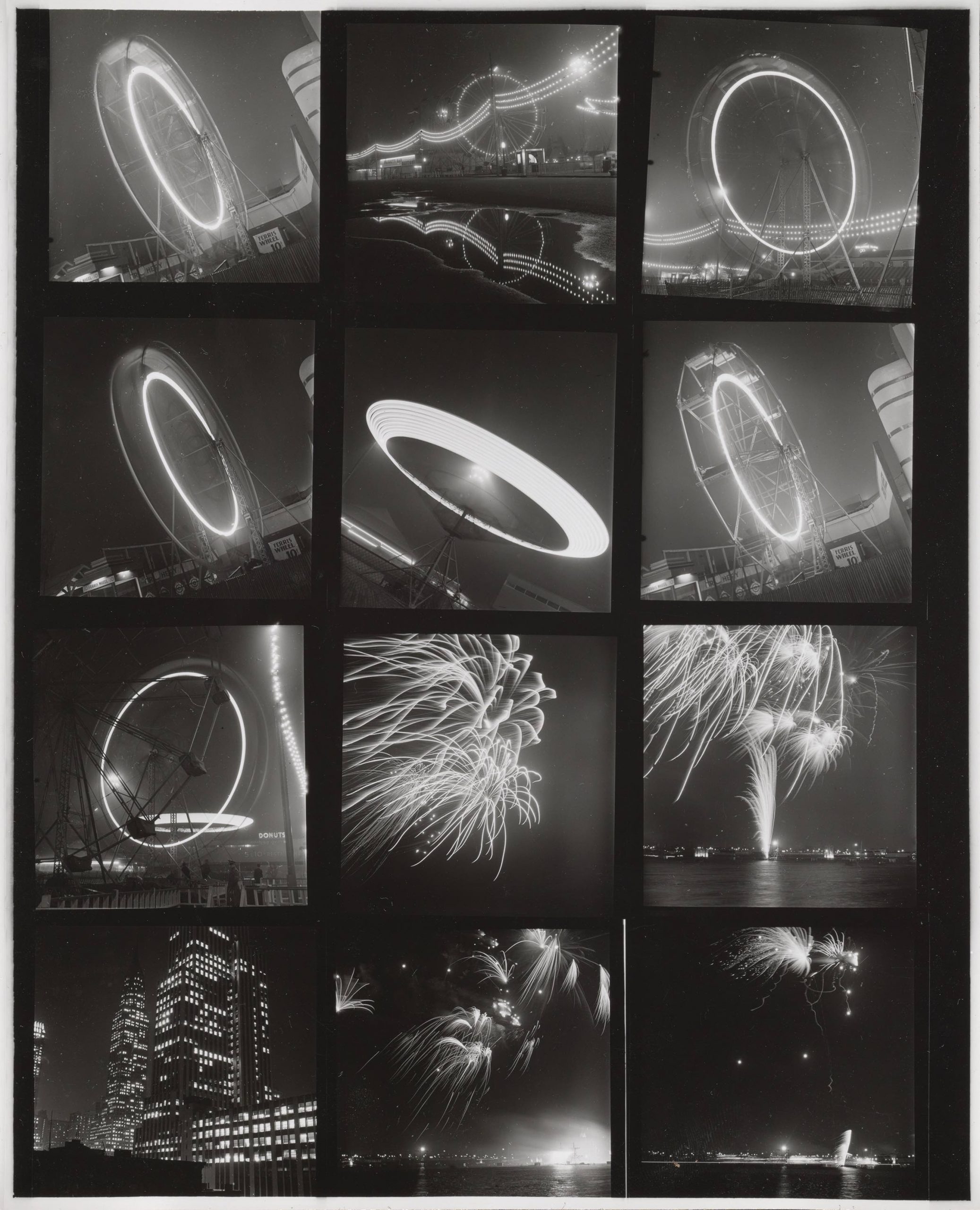

Contact sheet of the World's Fair 1939/40 by Andreas Feininger (© Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona).

Backside of the contact sheet of the World's Fair 1939/40 by Andreas Feininger (© Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona).

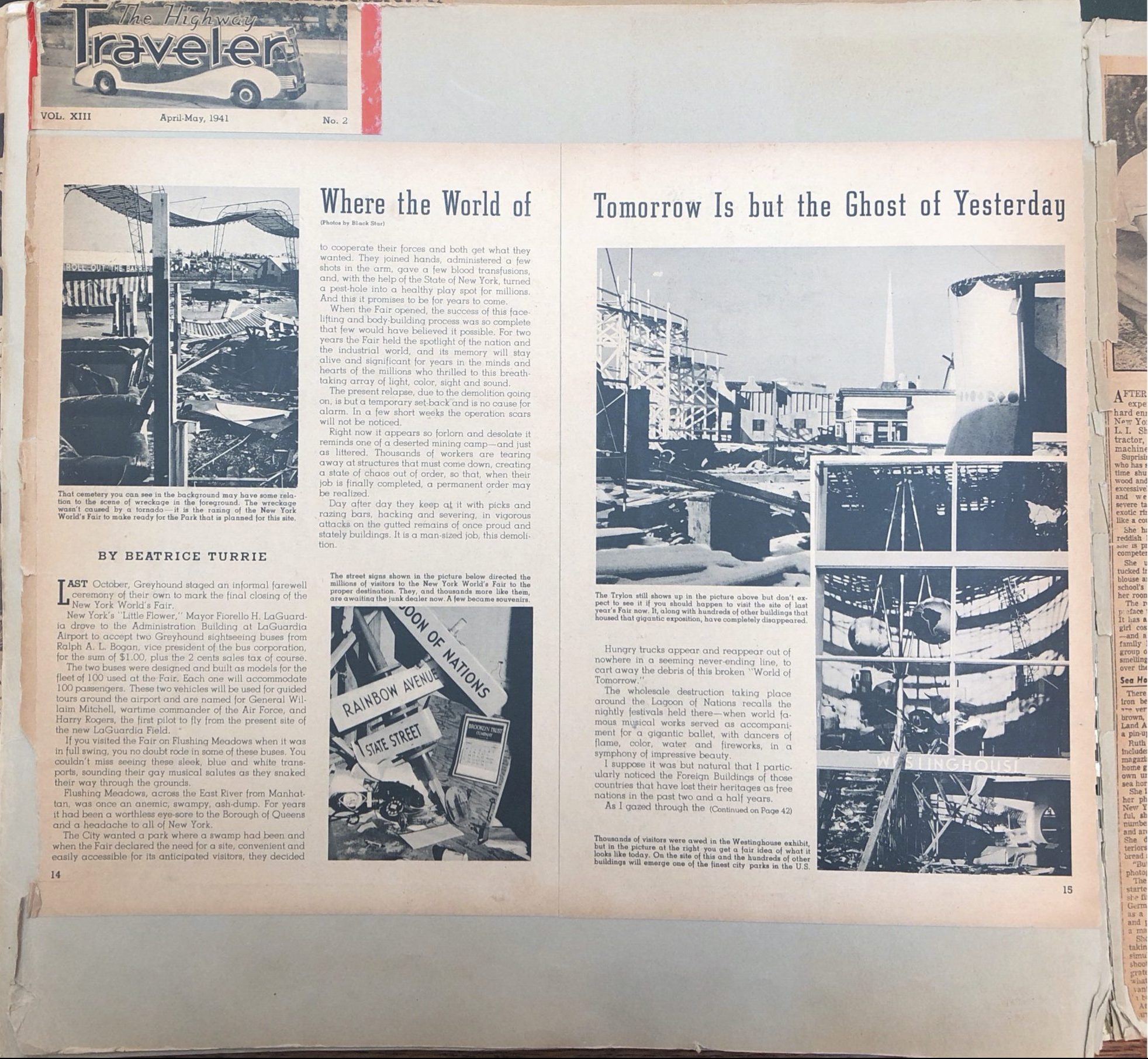

Unfortunately, the costs for the fair were high and the visitors not numerous enough; in 1940, it was thus forced to declare bankruptcy leaving behind a number of unpaid investors. All buildings and pavilions – most of them made of light material like gypsum, had to be demolished. Also, the symbols of the World Fair – the Tyron and Perisphere – were torn down. This emblematic moment was captured by the emigrated photographer Ruth Bernhard. Taught at the Academy of Art in Berlin in the 1920s, she came to New York in 1927, where she started taking photographs. In unusual perspectives, she captured scenic ruins like the “Skeleton of the Giant” – the title of one of her pictures. Her images were commissioned by the photo agency Black Star and published in a reportage for The Highway Traveler magazine.

Demolition of the World’s Fair by Ruth Bernhard. Reprint of the reportage “Where the World of Tomorrow Is But the Ghost of Yesterday.” The Highway Traveler, vol. 13, no. 2, April-May 1941, pp. 14–15.f.

For the next two decades, the site languished with empty streets and barren plots where the pavilions had formerly stood. In 1963/64, Flushing Meadows once again hosted the World’s Fair. Some of these architectural relicts can be still discovered when walking through the huge terrain of Flushing Meadows. The rest of the former World’s Fair area was to be incorporated into Queen’s district as a public park; on weekends, the old water basins and infrastructures are visited by a number of sports lovers.

Today’s area of the World’s Fair, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park with the Unisphere (where the Trylon and Perisphere stood)

Today’s area of the World’s Fair, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park with the New York State Pavilion (today's Queen’s Playhouse)

Today’s area of the World’s Fair, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park with empty water basins as football fields (Photo: Helene Roth, 2019).

Acknowledgements

My deepest thanks go to Peter Stein for providing photographs and archival material of the Estate of Fred Stein and Steven Wolff of the Estate of Werner Wolff. Geoff Alexander (The Academic Film Archive of North America), Rebecca Chase (University New Hampshire), Frauke Kreutler (Museum Wien), the New York Historical Society as well as the Center for Creative Photography (Tucson, Arizona).

Bibliography (selection)

Anonymous. Captured Light – An Exhibition of Experimental Photography. (Josef Breitenbach Archive, Center for Creative Photography Archives, The University of Arizona, Tucson), AG90:29.

Appelbaum, Stanley. The New York World’s Fair 1939/40 in 155 photographs. Dover Publications, 1997.

Atelier Lotte Jacobi. Berlin – New York, edited by Marion Beckers and Elisabeth Moortgat, exh. cat. Das Verborgene Museum, Berlin, 1997.

Bihler, Lori Gemeiner. Cities of Refuge. German Jews in London and New York, 1935–1945. SUNY Press, 2018.

Citron, W. M. Aufbau Almanac. The Immigrant’s Handbook. German-Jewish Club New York, 1941.

Cotter, Bill. The 1939–1940 New York World’s Fair. Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

Cuscuna, Michael, et. al. Blue Note. Jazz Photography of Francis Wolff. Universe Publishing, 2000.

Dreaming in Black and White. Photography at the Julien Levy Gallery, edited by Katherine Ware and Peter Barberie, exh. cat. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, 2006.

Feininger, Andreas. New York. Ziff-Davis Publishing Company, 1945.

Fred Stein. Dresden, Paris, New York, edited by Erika Eschebach and Helena Weber, exh. cat. Stadtmuseum Dresden, Dresden, 2018.

Heimat und Exil. Emigration der Deutschen Juden nach 1933, exh. cat. Jüdisches Museum Berlin / Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Berlin, 2006.

Hermann Landshoff. Portrait, Mode, Architektur. Retrospektive 1930–1970, edited by Ulrich Pohlmann and Andreas Landshoff, exh. cat. Münchner Stadtmuseum – Sammlung Fotografie, Munich, 2013.

Jackson, Naomi M. Converging Movements. Modern Dance and Jewish Culture at the 92nd Street Y. University Press of New England, 2000.

Köhn, Eckardt. Rolf Tietgens – Poet mit der Kamera. Fotografien 1934–1964 (Die graue Reihe, 57). Die Graue Edition, 2011.

Moreno, Barry. Ellis Island (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing, 2003.

Morris, John Godfrey. Get the Picture. A Personal History of Photojournalism. University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Panchyk, Richard. German New York City. Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

Rincke, Eva. Joseph Pilates. Der Mann, dessen Programm Name wurde. Verlag Herder, 2015.

Ruth Bernhard: Known and Unknown, edited by Constance W. Glenn, exh. cat. University Art Museum California State University, Long Beach, 1996.

Spalek, John M., editor. Deutschsprachige Exilliteratur seit 1933, Vol. 2: New York. Francke Verlag Bern, 1989.

Stölken, Ilona. Das Deutsche New York. Eine Spurensuche. Lehmstedt, 2013.

Torosian, Michael. Black Star. The Ryerson University Historical Print Collection of the Black Star Publishing Company. Lumiere Press, 2013.

Trude Fleischmann. Der selbstbewusste Blick, edited by Anton Holzer and Frauke Kreutler, exh. cat. Wien Museum, Vienna, 2011.

Vienna’s Shooting Girls. Jüdische Fotografinnen aus Wien, edited by Iris Meder and Andrea Winklbauer, exh. cat. Jüdisches Museum Wien, Vienna, 2012.

Walser, Robert. Keeping Time: Readings in Jazz History. Oxford University Press, 1999.