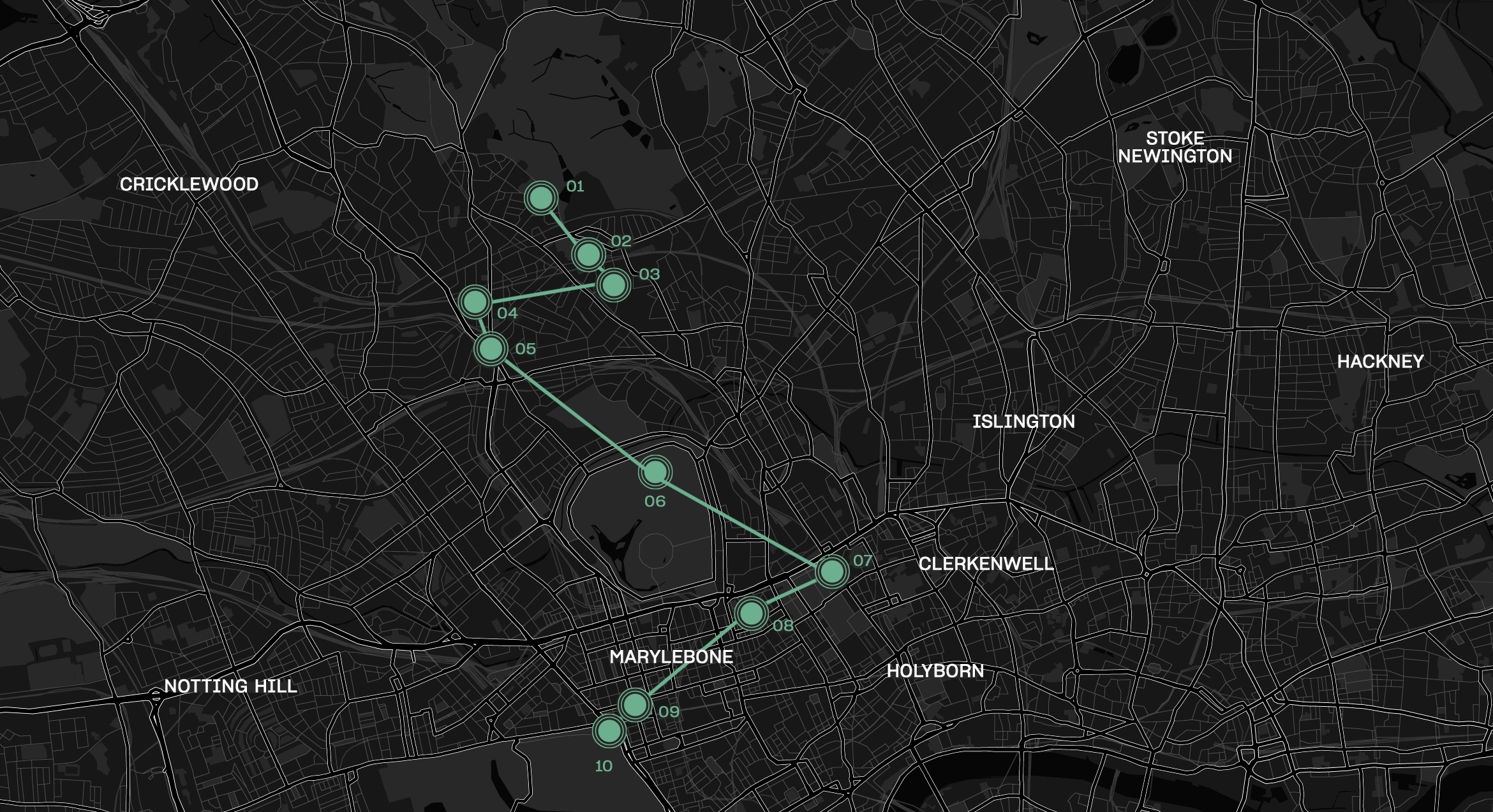

London

The Arts in Exile in the 1930s and 1940s: Urban Sites of Interaction

In the 1930s and 1940s, tens of thousands of emigrants fleeing from National Socialism came to London from the European continent, including painters, photographers, architects and designers. The walk will introduce key urban sites of artistic exile from Hampstead to Hyde Park, including private homes, institutions, but also social contact zones. In these still existing or forgotten places, emigrants met local artists, showed their work, gathered and received commissions or inspiration for their work. Nevertheless, the stops of this walk also show that the arrival in the exiled city of London was accompanied by struggles for artistic recognition. For most people, exile meant arriving without the possibility of returning to their homeland, as well as operating in a foreign language and from a new cultural environment. It has become clear that exile challenged the émigrés, but also that urban spaces offered numerous opportunities for negotiation, communication and exchange, making it possible for emigrants to “arrive”.

miles 155

min. 10

sights By Foot

01Goldfinger House/ 2 Willow Road, Hampstead

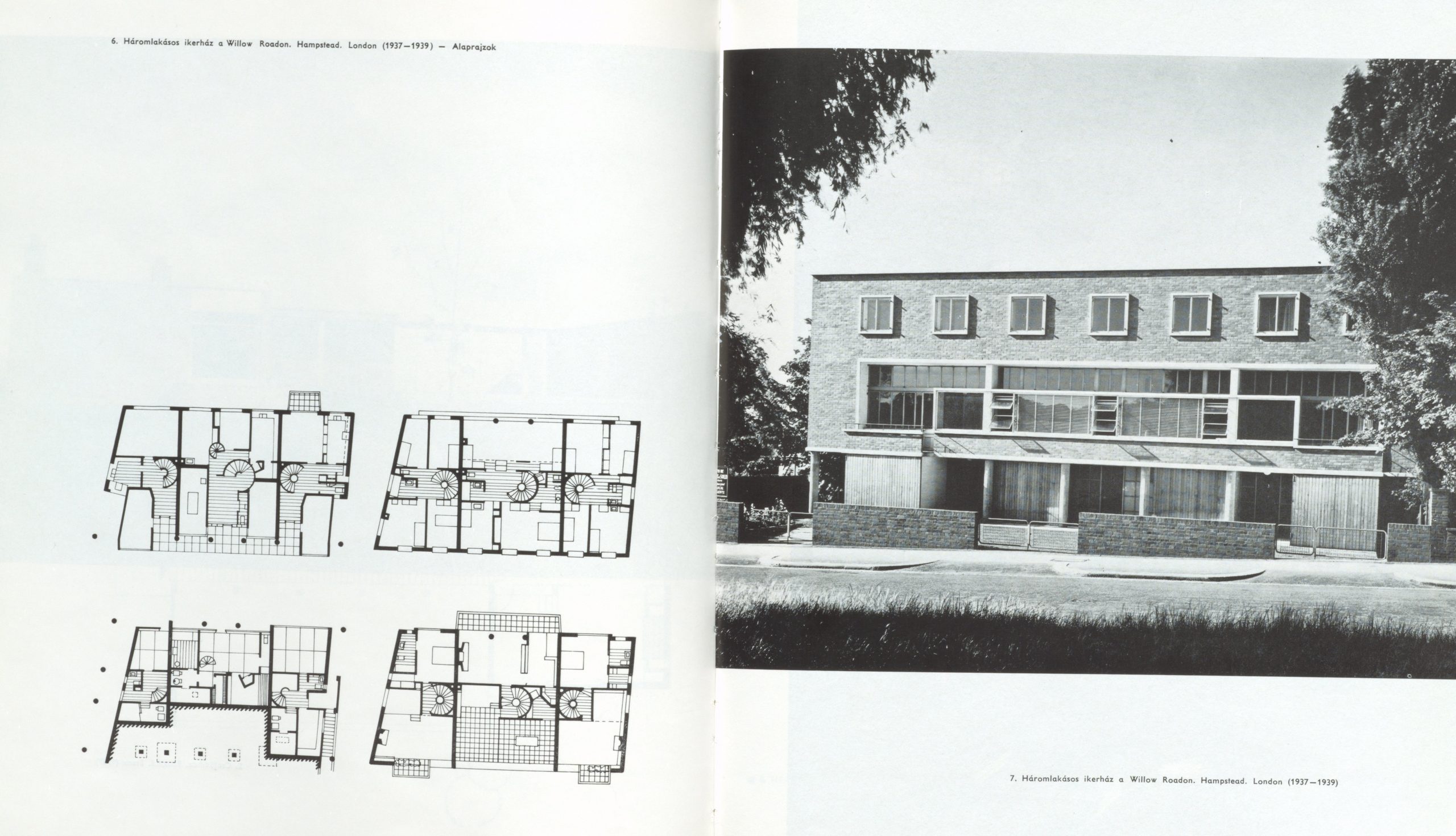

The walk begins at the house of the architect Ernö Goldfinger and his wife, the painter Ursula Goldfinger. The Goldfingers had moved from Paris to London in 1934. In 1937 the architect designed three row houses in reinforced concrete skeleton construction on a plot of land overlooking Hampstead Heath. The Goldfingers lived in the middle townhouse, the other townhouses were rented or sold. Ernö Goldfinger’s design provoked opposition from the Hampstead Heath and Old Hampstead Protection Society, which disagreed with his modernist building principles and was concerned about the unity of the historic neighbourhood. Although Goldfinger’s house was built with an awareness of local building traditions, it broke with accepted notions of living in England by postulating a connection to continental modernism through its outer cubic form, wide windows, flat roof and pilotis on the street side. The building has three storeys to the front and four storeys to the rear; the basement or ground floor to the garden side contained a garden room and the maid’s bathroom. Above, were the kitchen and two domestic workers’ rooms. On the first floor there were living and dining rooms, a “garden room” downstairs provided direct access to the back garden.

Ernö Goldfinger, 2 Willow Road, 1939, street view (Photo: Mareike Hetschold/Sonja Hull, 2017).

Goldfinger House and floor plans of the three townhouses (Máté 1973).

Goldfinger was progressive in his flexible treatment of the floor plan; the rooms on the first floor could be turned into one large room by means of mobile walls — according to the needs of the owners. For social occasions but also for exhibitions that the Goldfingers held here, the private apartment could thus be transformed into a (semi-)public space with a correspondingly prestigious floor plan. Not only the floor plan and the façade design were innovative, but also the built-in cupboards and shelves, which made heavy and voluminous furniture obsolete. The photobolic screen can also be considered a novelty and became Goldfinger’s trademark; an internal construction within the windows and an inner frame of concrete divide the upper third of the windows so that the light can both be maximized and diffused, bringing light all the way to the back of the room.

Ernö Goldfinger, 2 Willow Road, Hampstead, 1939, interior, dining room, photo: Dell & Wainwright (Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections, RIBA8557). The flexible floor plan of the building was particularly innovative in that it allowed variable use of space.

02Isokon Building (Lawn Road Flats)/ Lawn Road, Hampstead

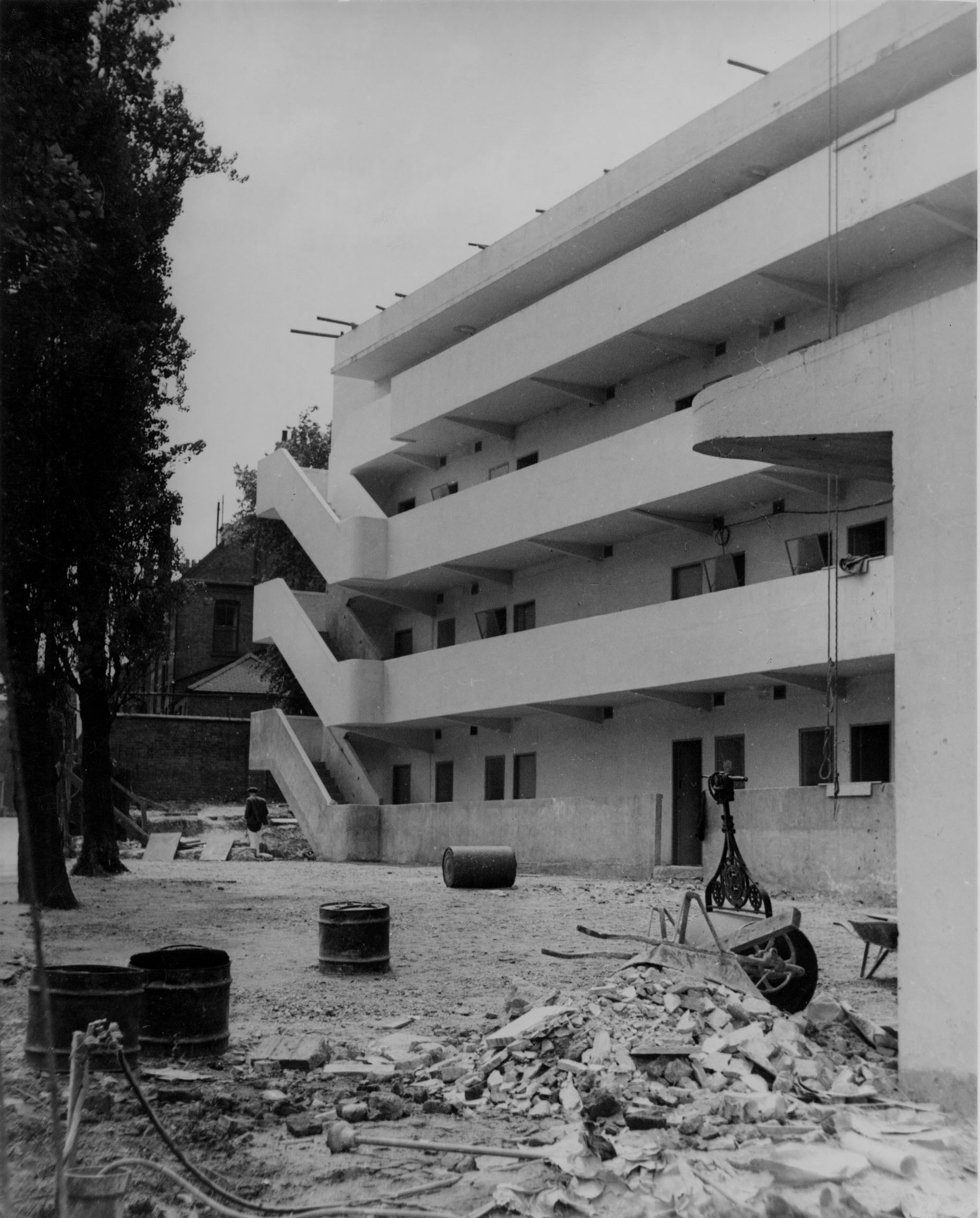

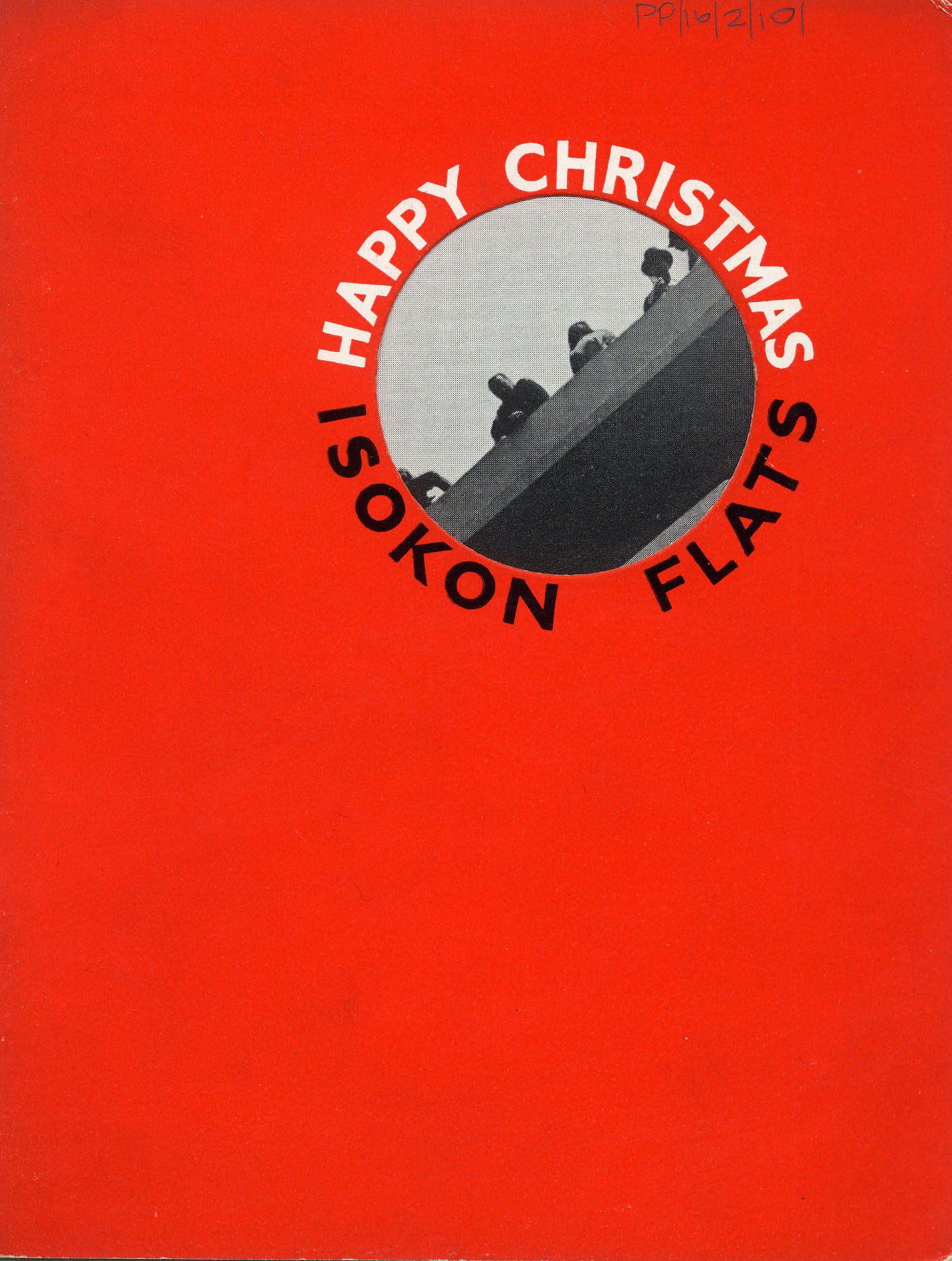

Around ten minutes’ walk from the Goldfinger House in 2 Willow Road and located also in the suburb of Hampstead are the Lawn Road Flats, the so-called “Isokon Building”. The Isokon Building was an urban location of particular importance for émigré artists, a place for communicating and forming networks; it was also a stopover on diverse paths of exile. Designed by the architect Wells Coates and commissioned by Jack Pritchard, the flats were completed in 1934. The conception of the Isokon Building was based on principles of urban ‘good living’ and a reduced living space that was to nonetheless offer all the conveniences deemed necessary for comfortable living, such as built-in cupboards, sliding doors, a dressing room and a small kitchen. In addition, service and community facilities were planned, for example a large kitchen on the ground floor that was to provide residents with meals on order. In 1937 this kitchen was converted into a restaurant and bar, the ‘Isobar’, which became the social hub of the building.

The emigrated London based photographer Edith Tudor-Hart, a friend of Jack Pritchard and sister of the photographer Wolf Suschitzky, took a series of photographs of the building process and the opening of the building in 1934 (Pritchard Papers, University of East Anglia © The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

Today, after restoration in the 2000s, the Lawn Road Flats still resemble the original designs very closely (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2018).

The flats in the Isokon building are in private ownership and cannot be visited (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2018).

An exhibition gallery was created in the former garage, communicating the ideas and the histories of the building to a wider audience (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2018).

Edith Tudor-Hart, Lawn Road Flats Christmas card, 1934, cover (Pritchard Papers, University of East Anglia © The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

Edith Tudor-Hart, Lawn Road Flats Christmas card, 1934, inside (Pritchard Papers, University of East Anglia © The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

Edith Tudor-Hart, Terrace of the Isobar overlooking the Isobar garden, c. 1930s, (Pritchard Papers, University of East Anglia © The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

The Isobar was fitted with furniture by Isokon, designed by the émigré Bauhaus artist Marcel Breuer. A map of northwest London was pinned to the wall next to the bar. City, map and bar were thus brought together conceptually, and the Isobar was marked as an urban location for amusement and conversation. The tenants of the Lawn Road Flats socialized in the Isobar, rubbing shoulders with prominent guests, including the artists Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, who lived nearby, or the biologist Julian Huxley and the sculptor Naum Gabo. The Isobar was thus a site where food was celebrated as a social act. With respect to the history of exile in London, the bar was a prominent contact zone and location for forming a social community — and a place to be for the residents of the Lawn Road Flats, among them the founder and director of the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau, Walter Gropius, his wife Ise Gropius and the designer Marcel Breuer.

The Isobar, photo: Dell & Wainwright, c. 1937 (Pritchard Papers, University of East Anglia).

While Gropius had tried to establish himself as a freelance architect, and he had also worked as the Art Director of Isokon Furniture Company. As noted above, the owner of Isokon was Jack Pritchard, the initiator of the Lawn Road complex. And Marcel Breuer, another Lawn Road resident, was responsible for a collection of Isokon furniture made of plywood, for which he translated his aluminium seating furniture into an aesthetic more fitting the wooden material. Another Bauhaus member (but not Isokon resident), the designer and photographer László Moholy-Nagy, created show cards and sales leaflets for Isokon. Beyond this, the service house also had a secret history: During wartime, residents of the Lawn Road Flats were linked to the Russian intelligence, conducting spying operations for the Soviet Union. This was after the Bauhaus émigrés had left London and the Isokon Building: Breuer, as well as Walter and Ise Gropius, emigrated to the United States in 1937, where they continued their architectural and design practice and taught at Harvard.

Walter Gropius, his wife Ise Gropius and the designer Marcel Breuer attended the first anniversary of the Isokon Building in 1935, alongside the émigré architect Arthur Korn (Carr 2004).

03Free German League of Culture (Freier Deutscher Kulturbund)/ 36 Upper Park Road, Hampstead

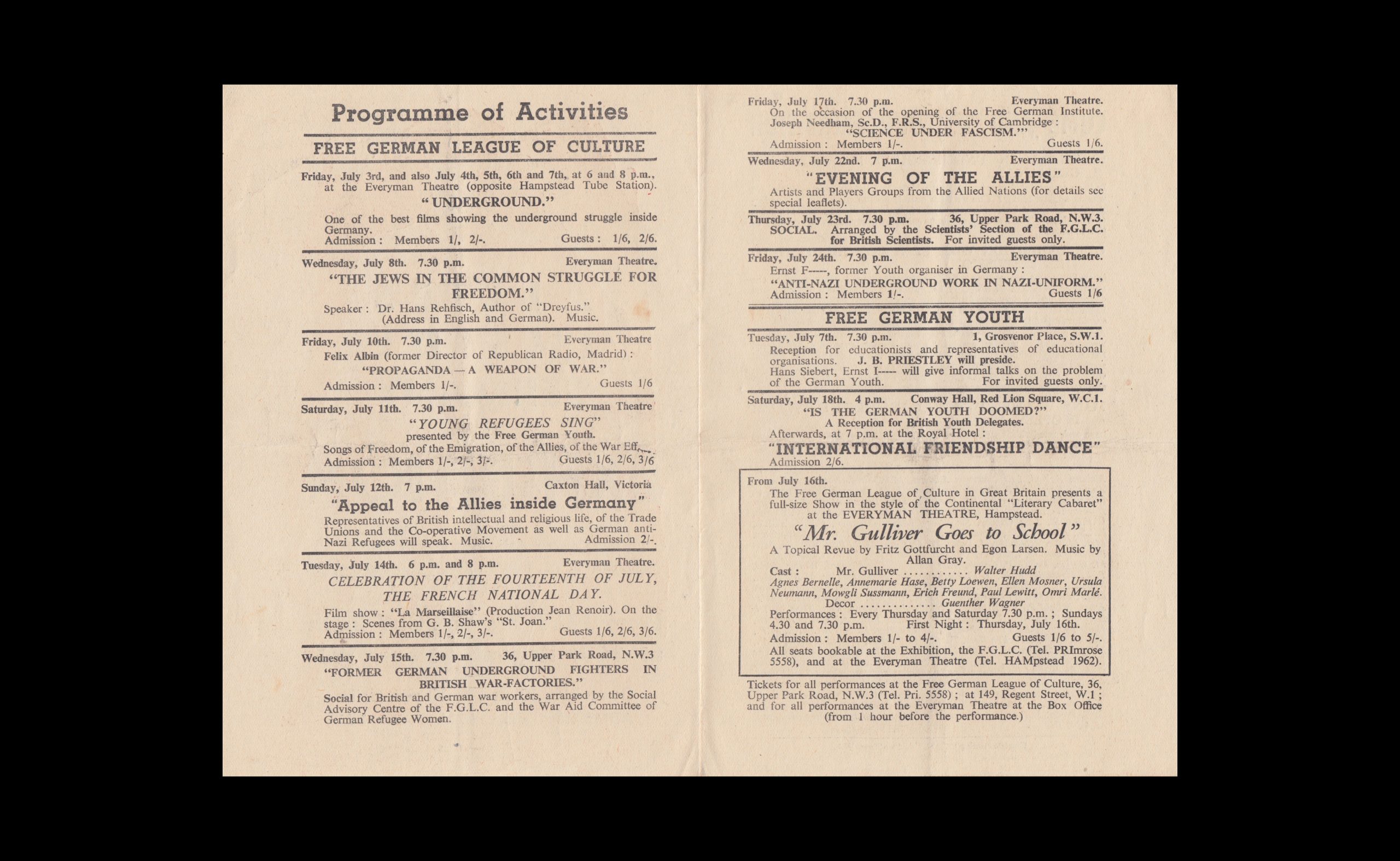

Founded at the end of 1938 by German-speaking emigrants, the Free German League of Culture (Freier Deutscher Kulturbund) was an association of artists and writers that organized exhibitions, readings, concerts and plays. At the end of 1939, the League moved into new headquarters in Hampstead. The Free German League of Culture was committed to preserving free German culture outside Nazi Germany, to promoting understanding between the English population and the refugees, and to maintaining solidarity with democratic, liberal and progressive movements. The organization gave its members a certain power of action by allowing them to be active in the organization and to participate artistically and culturally. The events were mainly attended by the emigrant community, but local audiences were also addressed, and Britons were involved in the League’s boards. In its communication organ, the bulletin Freie Deutsche Kultur, the League informed its members about its activities in German. The Free German League of Culture disbanded in 1946.

36 Upper Park Road – the clubhouse of the League from 1939 (Photo: Julia Winckler, originally used in Brinson/Dove 2010).

“Wir haben ein Haus” – Announcement of the new clubhouse in Freie Deutsche Kultur, newsletter of the Free German League of Culture, 1939, no. 12 (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

The Art Section of the Free German Cultural Association organized several exhibitions, sometimes in cooperation with other organizations such as the Artists’ International Association (AIA): among them were the group exhibitions Refugee Artists and their British Friends (1941) or Exhibition of Drawings, Paintings and Sculptures (1944), which promoted the work of members and other artists. In addition to this objective, the sales exhibitions also had other concerns: for example, to collect money to support internees in camps such as those on the Isle of Man or in Canada. The exhibition Artists Aid Jewry, shown in 1943 in the Whitechapel Art Gallery, supported Jewish victims of Nazi persecution. The exhibition Allies Inside Germany in 1942 had an educational purpose since it referred to the resistance in Nazi Germany and at the same time stood up for the emigrant community as representatives of another Germany: Allies Inside Germany was opened in a vacant shop in Regent Street and then went on an exhibition tour through Great Britain. René Graetz’s invitation leaflet for the exhibition, designed in red, shows a male figure, identifiable as a worker by his clothing and cap, standing wide-legged with a clenched fist. Graetz links this depiction to the Roter Frontkämpferbund from the time of the Weimar Republic, where the (actually raised) clenched fist was used as a sign of anti-fascist resistance.

Allies Inside Germany exhibition, 1942, leaflet, cover by René Graetz (METROMOD Archive).

Allies Inside Germany exhibition, 1942, leaflet, programme of activities (METROMOD Archive).

04Freud House/ 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead

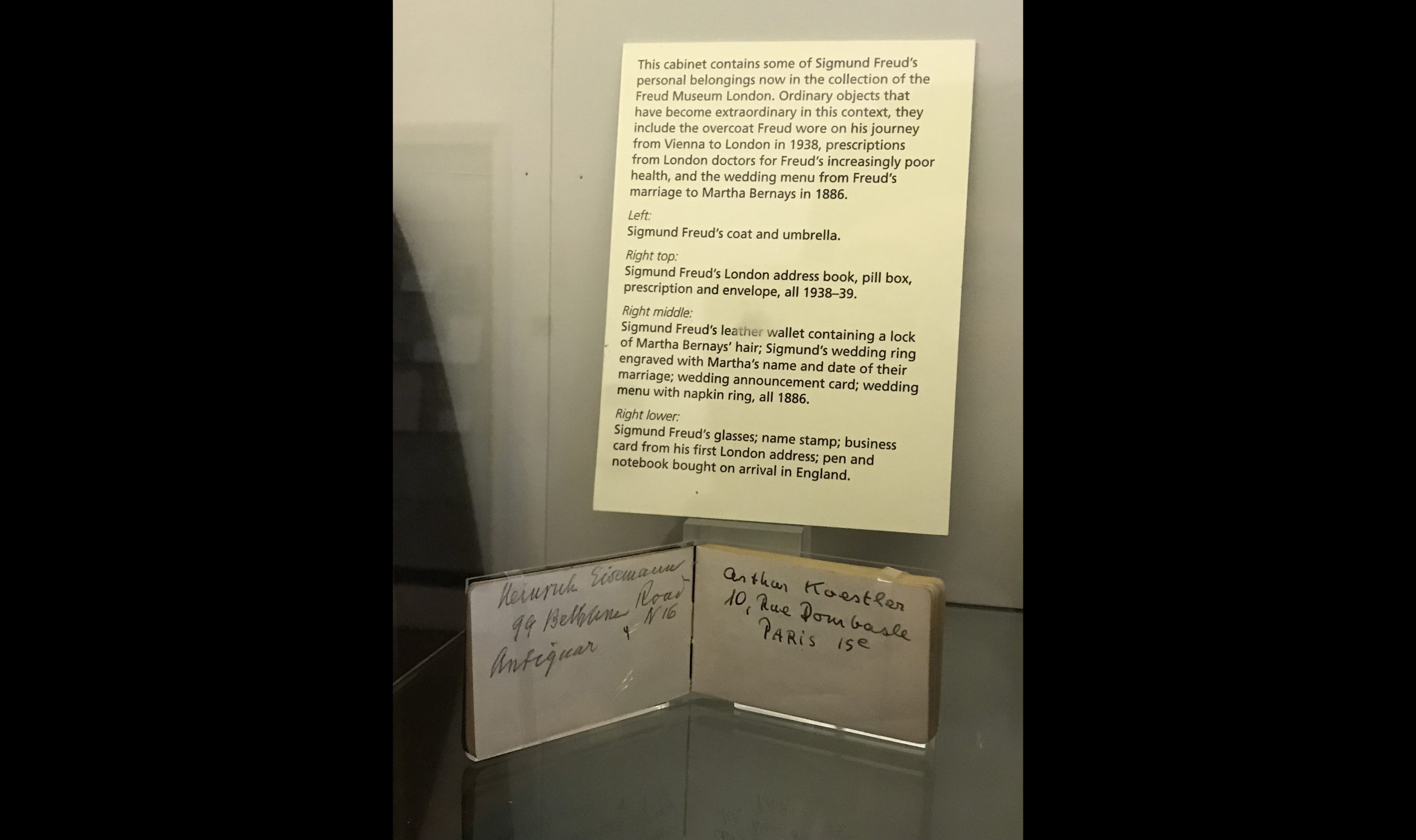

In the immediate vicinity of the Free German League of Culture one can find the house of the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud and his family, who left their hometown of Vienna in June 1938, fleeing from the National Socialists. While Freud had to leave parts of his extensive library behind in Vienna, he managed to take the largest part of his collection of antiquities with him into exile in London. Freud kept the antiquities in his two Viennese workrooms, where he wrote and carried out his psychoanalysis. The collection pieces can be described as an integral part of his professional life. When Freud’s family fled Vienna, they tried to keep the collection in order. In London, too, the pieces were once again placed on Freud’s desk and vitrines, and thus found their place in the part of the house where they were used most for his work. An important person in charge of this reconstruction work was Freud’s son, the architect Ernst L. Freud, who had already emigrated to London in 1933 and who rebuilt the house in Maresfield Gardens.

Walking down the street towards the Freud House – which is now the Freud Museum London (Video: Burcu Dogramaci, 2018).

Freud House at Maresfield Gardens (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2018).

Address Book of Sigmund Freud, exhibited at the Freud Museum (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2018. Courtesy of the Freud Museum London).

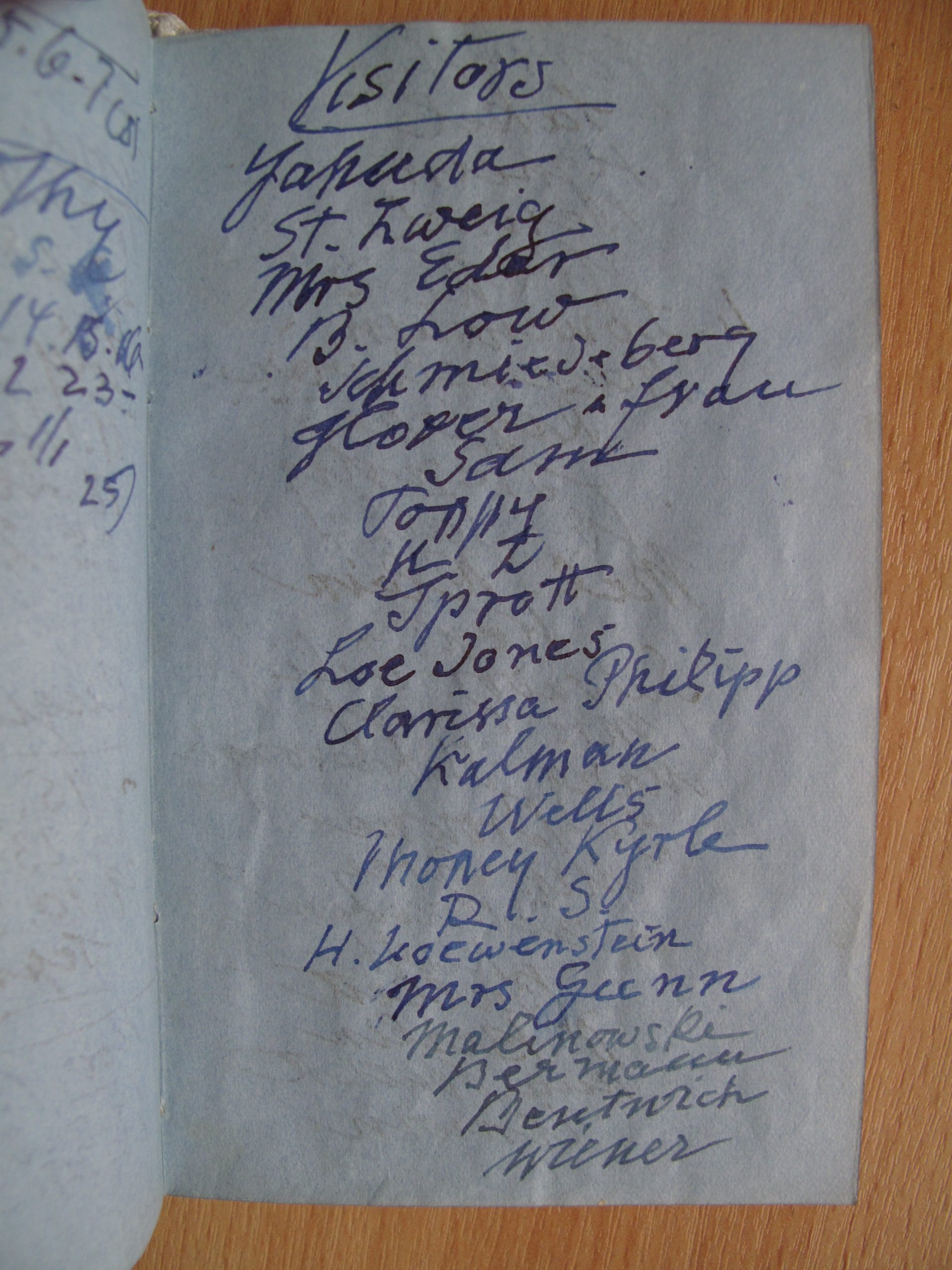

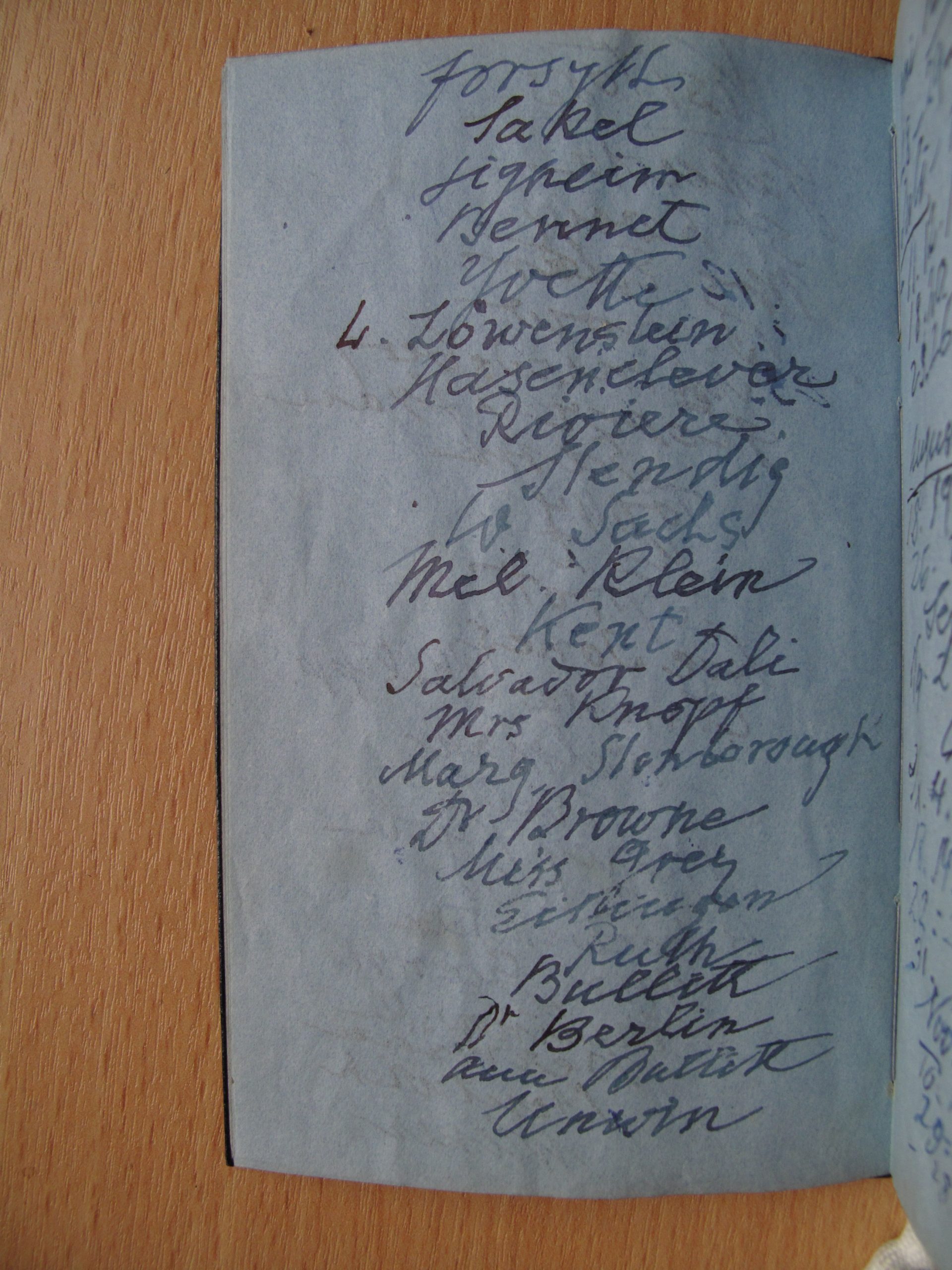

Unlike in Vienna, Freud’s study and treatment rooms were not housed in two rooms but merged into one. The aim was to integrate the migrated furniture such as the desk and the expressive desk chair — a design by the architect Felix Augenfeld — as well as the couch into a new dramaturgy, while retaining the essential character of these set pieces that were central to Freud’s work. In London, Freud was in contact with artists and writers such as Salvador Dali, who painted his portrait, and Stefan Zweig. Zweig also gave the funeral speech at the ceremony following Freud’s death in September 1939. After Freud passed away, Martha Freud and her daughter Anna Freud left the workrooms largely in their original state. Anna Freud, who built a career as a psychoanalyst for children in London, lived in Maresfield Gardens until her death. In 1986, the Freud Museum in London was opened in Freud’s home and thus the memory of Freud’s existence in Vienna was finally preserved for posterity.

Visitor Book with Freud’s London visitors of 1938 and 1939 – below, the painter Salvador Dalí and the writer Stefan Zweig (© Freud Museum London)

Visitor Book with Freud’s London visitors of 1938 and 1939 – below, the painter Salvador Dalí and the writer Stefan Zweig (© Freud Museum London)

Study Room of Sigmund Freud, contemporary installation view, Freud Museum, London (© Freud Museum London).

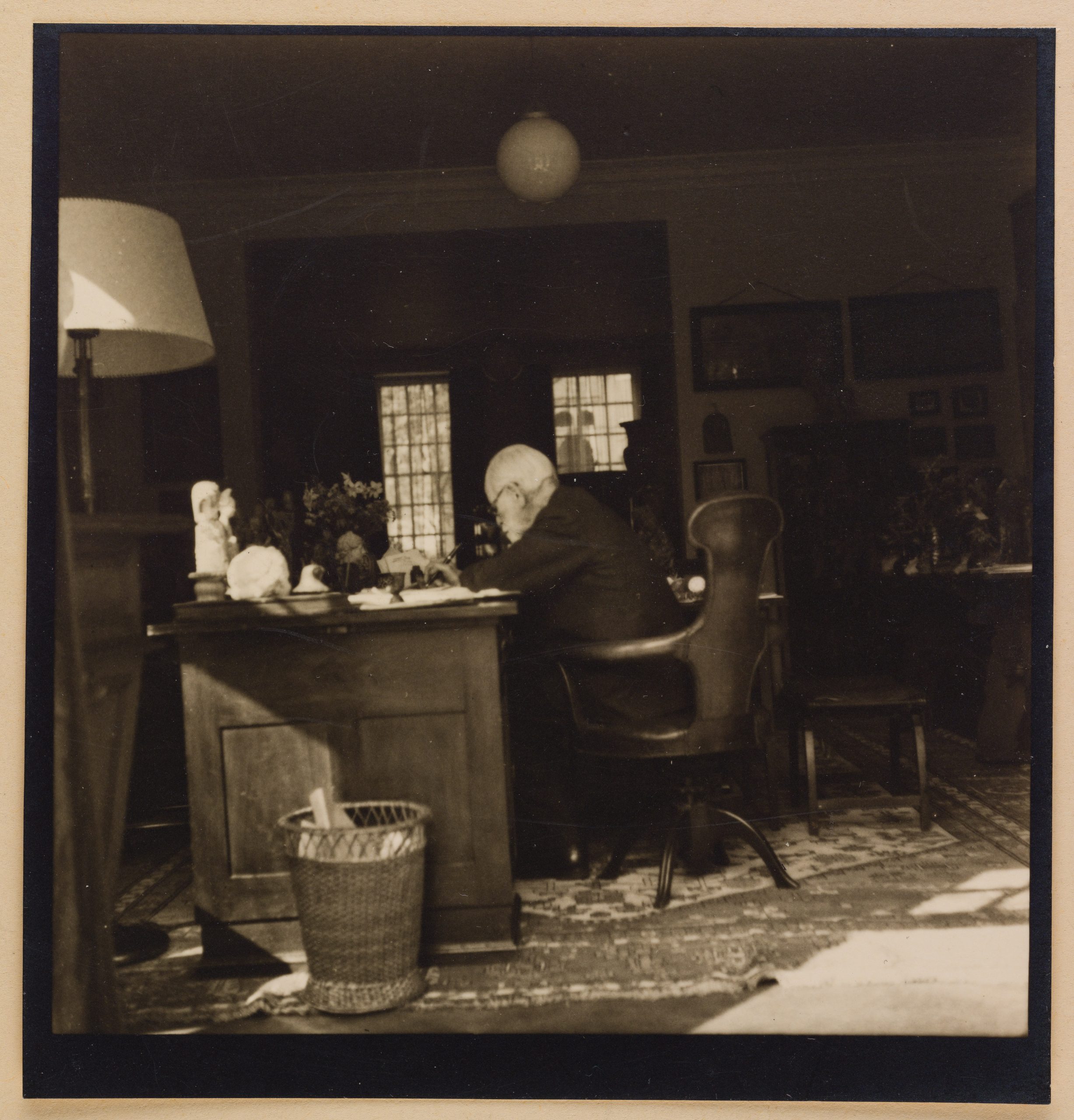

Freud at his desk in London. The desk chair was designed by the Viennese architect Felix Augenfeld and was adapted to Freud's unique reading posture: the psychoanalyst sat in a diagonal position on the chair with one leg laid across the backrest (© Freud Museum London).

Anna Freud and her partner Dorothy Burlingham opened the War Nursery research and care facility at two sites in Hampstead in 1941 (13 Wedderburn Road; 5 Netherhall Gardens). They published the Annual Report of a Residential War Nursery in 1942 (Private Archive).

Dorothy Burlingham and Anna Freud. Anstaltskinder. Imago Publishing, 1950, title page (METROMOD Archive). German version of Infants without Families, 1943, a study in the context of War Nursery research and care facility.

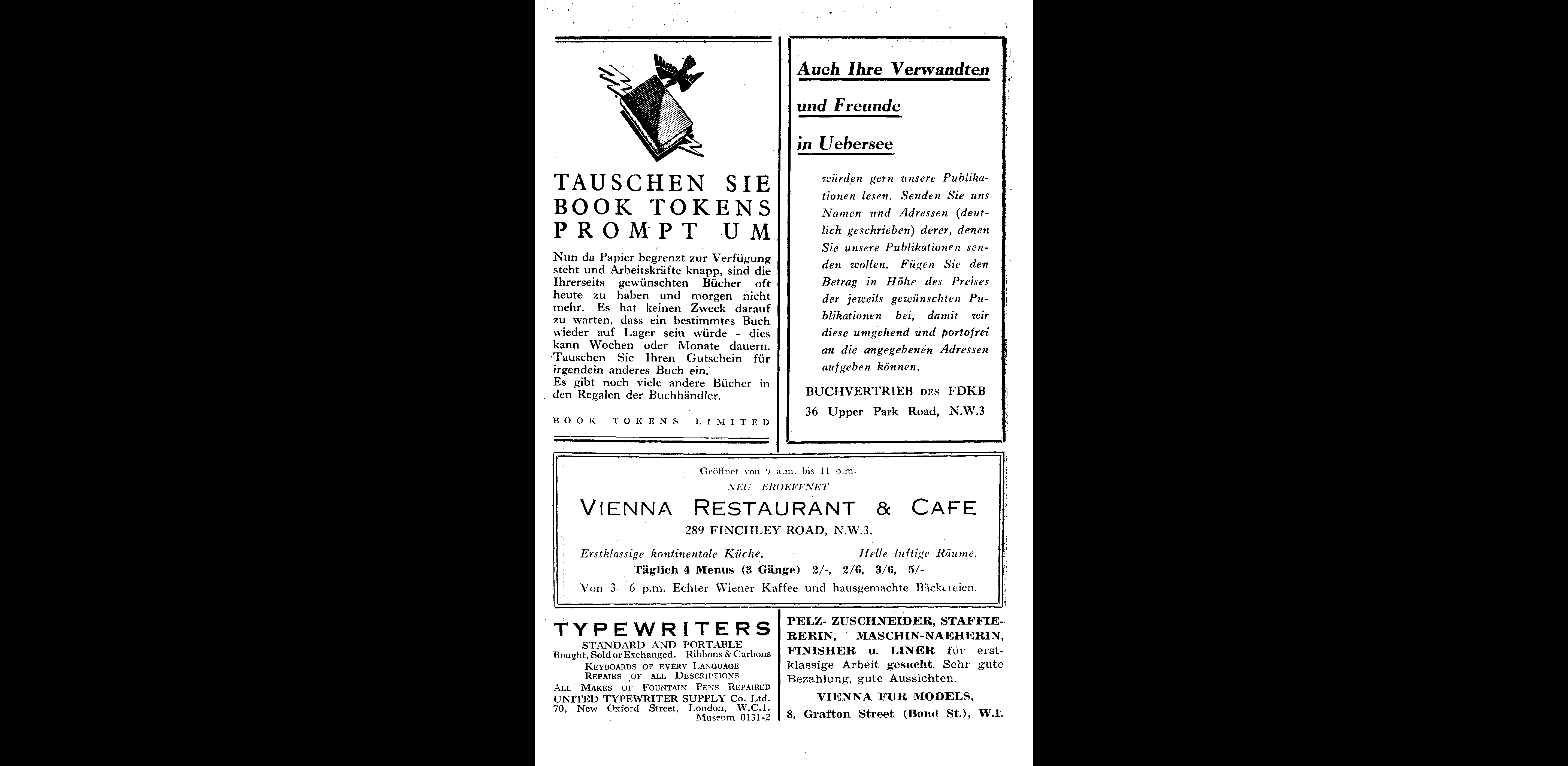

05The Cosmo Restaurant, 4-6 Northways Parade/ Finchley Road, Swiss Cottage

Between 1933 and 1998 The Cosmo restaurant and café were located only a six minutes’ walk from Sigmund and later Anna Freud’s house. It offered Austrian dishes such as Wiener Schnitzel or pastries and was a central meeting place for German-speaking emigrants, including Elias Canetti, Erich Fried and Sigmund Freud. The Cosmo was an important social contact zone created by exiles for exiles, a place of information exchange among people with shared experiences of flight. Larger communities often bring their own infrastructures to their “Arrival Cities” (Saunders 2010) (as is still the case today); in addition to grocery stores, this includes cabarets and restaurants such as the Vienna Restaurant & Café at 289, Finchley Road. Here, people who had settled in the area were offered home-related goods or culture that provided them with a common frame of reference. Identification and memory, language, taste and smells found their expression in these social spaces of emigration. In exile, cooking and eating can symbolise belonging to a group, revive positively connoted memories of the time before emigration, and help to stabilise the individual.

The exterior of the Cosmo restaurant, 1965 (© Marion Manheimer).

Customers at the Cosmo restaurant, 1965 (© Marion Manheimer).

A plaque, which was initiated by the Association of Jewish Refugees, commemorates the no longer existing restaurant The Cosmo (Herman 2019).

Vienna Restaurant & Café was located in the proximity of The Cosmo at Finchley Road. Advertisement in Freie Deutsche Kultur of the Free German League of Culture, April 1944, p. 15 (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

06London Zoo/ Outer Circle, Regent’s Park

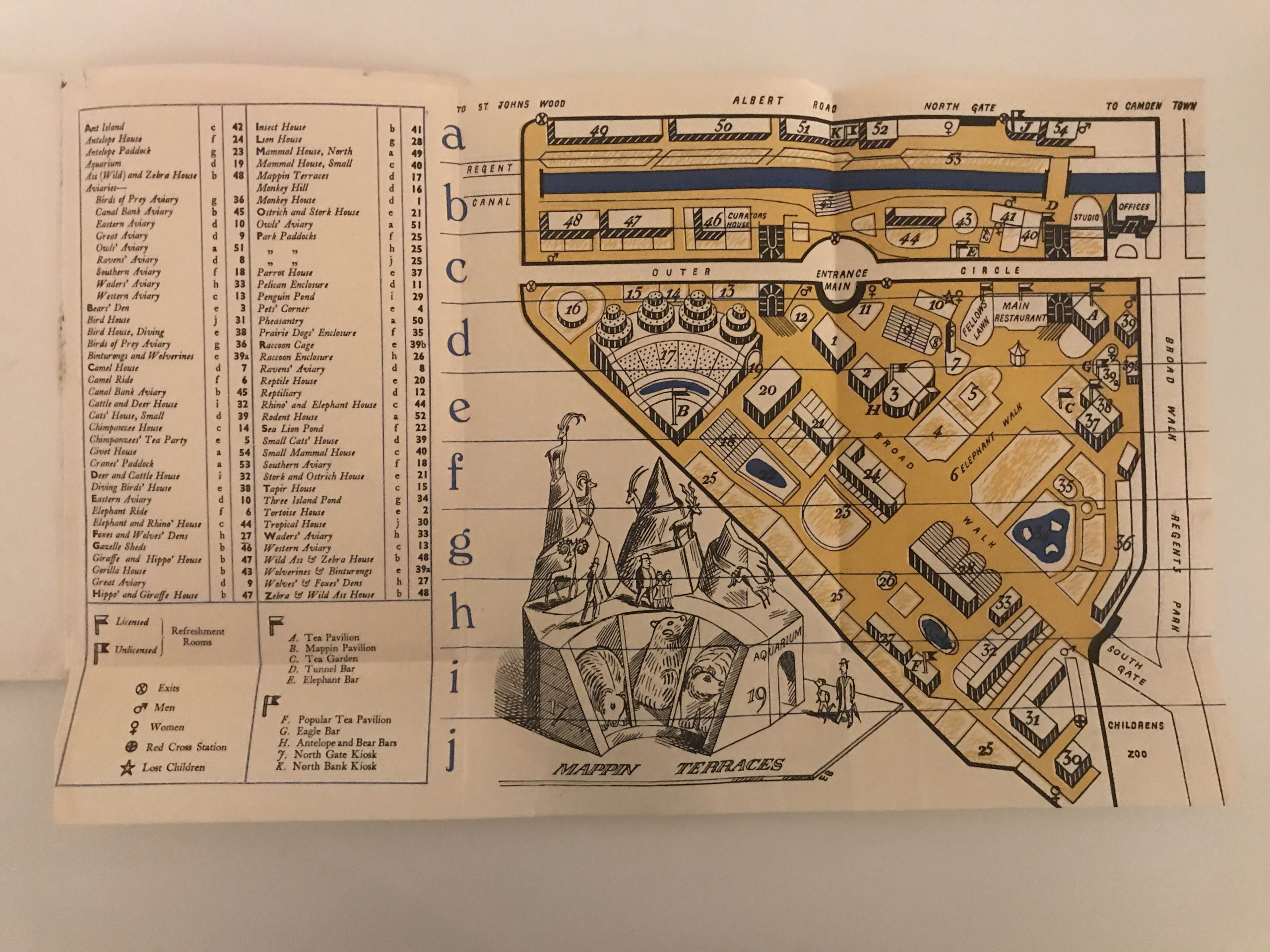

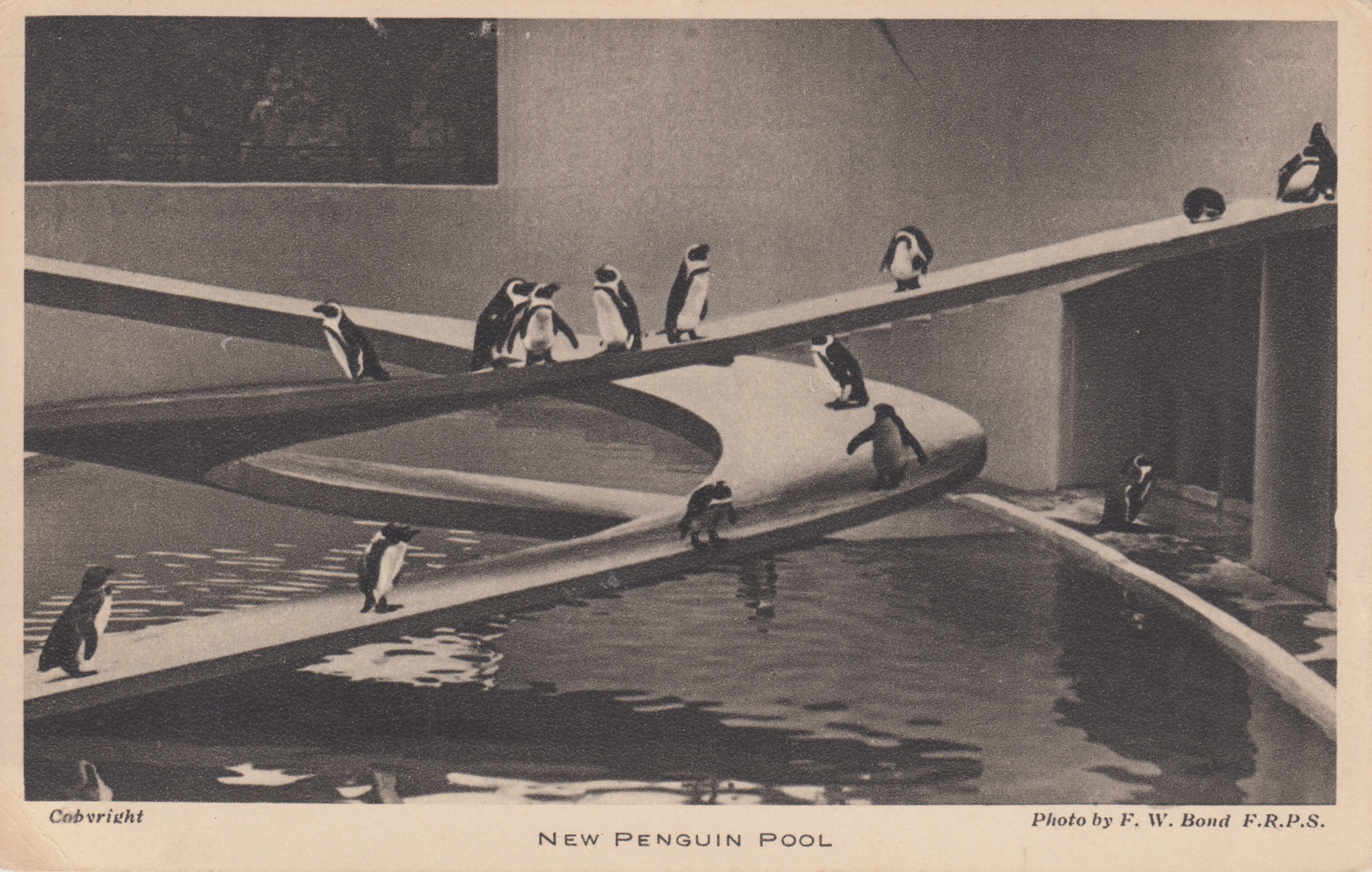

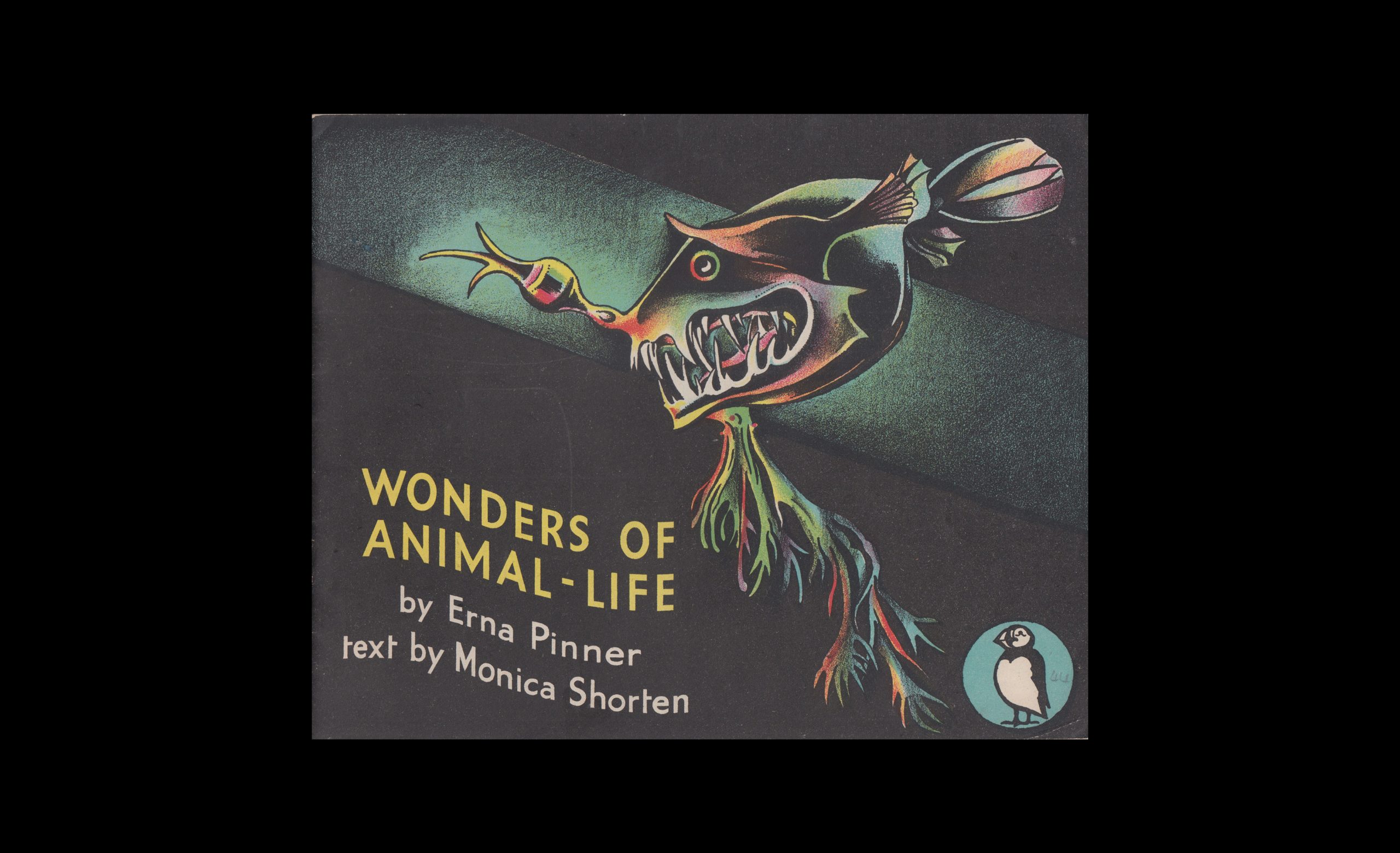

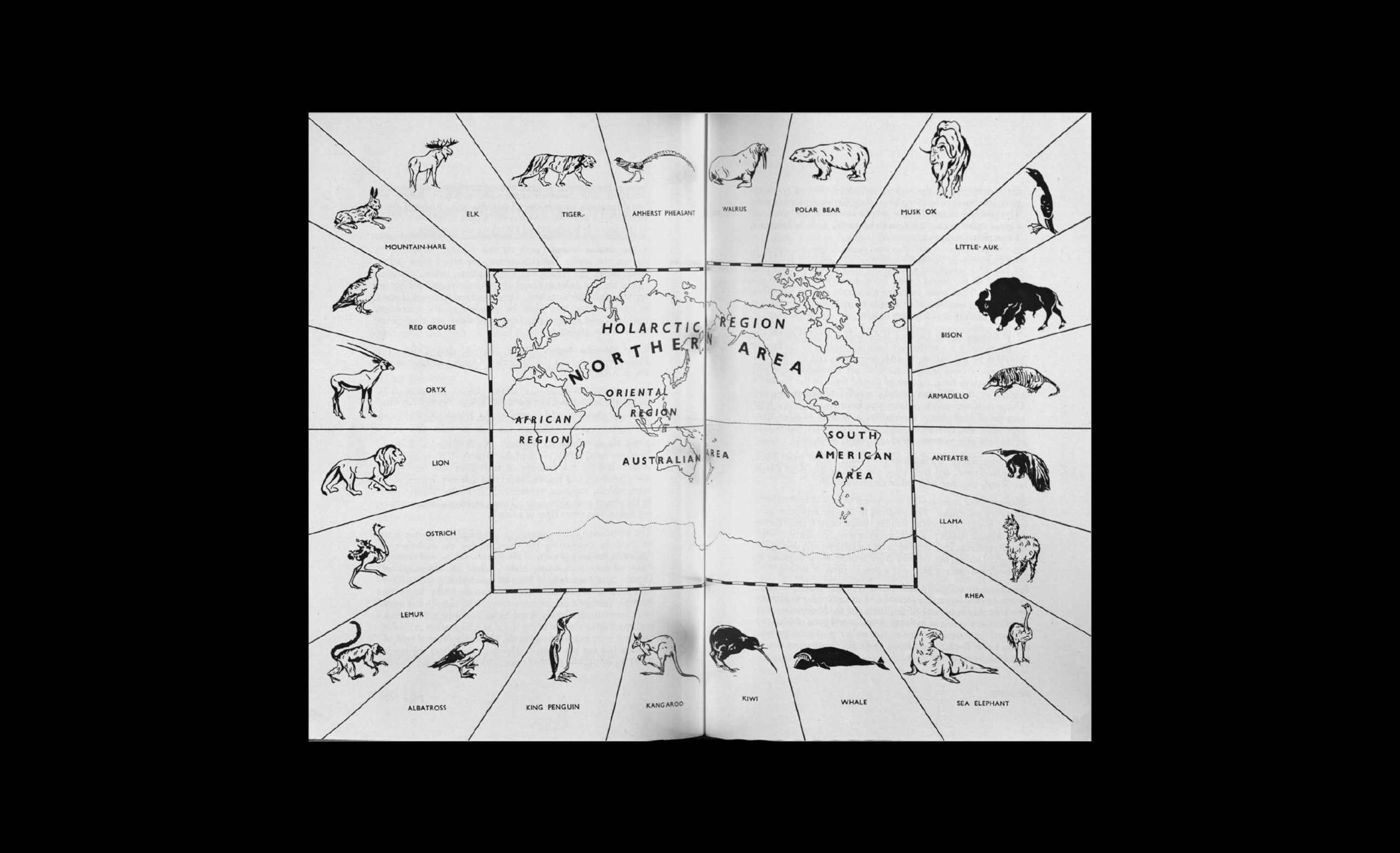

London Zoo is a node in the network of artistic emigration. The Penguin Pool (1934), designed by the emigrated architect Berthold Lubetkin and his firm Tecton, was a particularly popular attraction. The short film The New Architecture and the London Zoo (1936) by Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy referred to Lubetkin’s buildings at London Zoo and Whipsnade Zoo at the countryside. Many emigrants had connections to the secretary of the Zoological Society of London, Julian Huxley, who gave them commissions. Erna Pinner, who emigrated to London in 1935, was introduced to the British Zoological Society by Julian Huxley. In 1937 she contributed a “map of geographical distributions” to the official Zoo Guide, and in the following years she was responsible for numerous animal illustrations for books such as Felix Salten’s Bambi’s Children (1940) and A Book of Animal Verses (1943). Her scientific illustrations are executed with both meticulous accuracy and a specific artistic signature. The results of her animal observations in the wild as well as at London Zoo have been documented in books such as Wonders of Animal Life (1945) and Curious Creatures (1951).

Plan of London Zoo (Julian S. Huxley. Official Guide to the Gardens and Aquarium of the Zoological Society of London. Colman, Prentis and Varley Ltd., 1936).

F. W. Bond, New Penguin Pool, Architecture: Berthold Lubetkin/Tecton, 1934, postcard around 1937 (METROMOD Archive).

Erna Pinner. Wonders of Animal-Life. Penguin Books, 1945, cover (METROMOD Archive, Original © Erna Pinner).

Erna Pinner. “Map of geographical distribution.” Julian S. Huxley. Zoo. Official Guide to the Gardens and Aquarium of the Zoological Society of London, 1937, pp. 102f. (ZSL Library, London, Original © Erna Pinner).

László Moholy-Nagy, The New Architecture and the London Zoo, 16mm black-and-white film, silent, duration 16 min., excerpt (© Courtesy of the Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

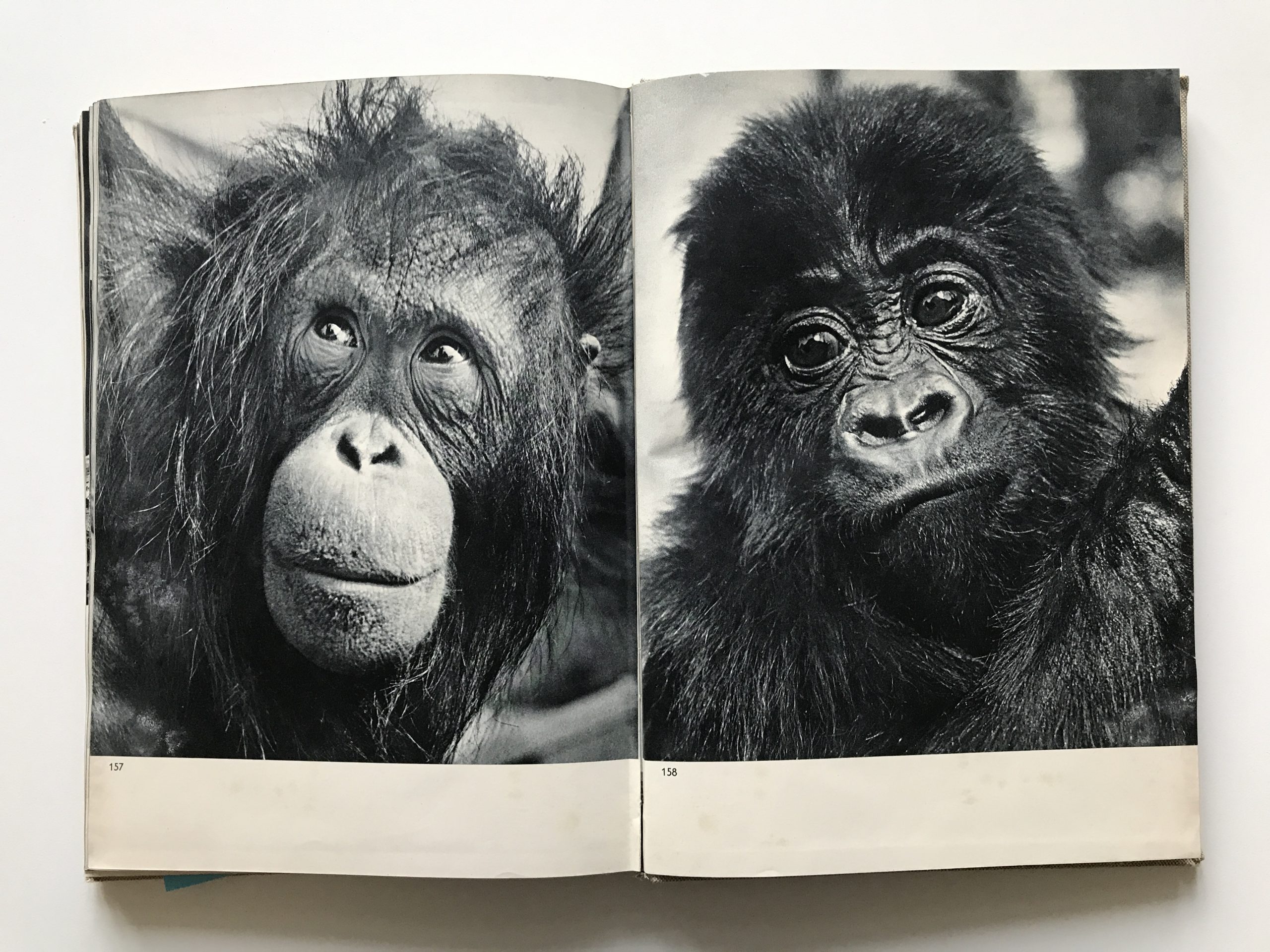

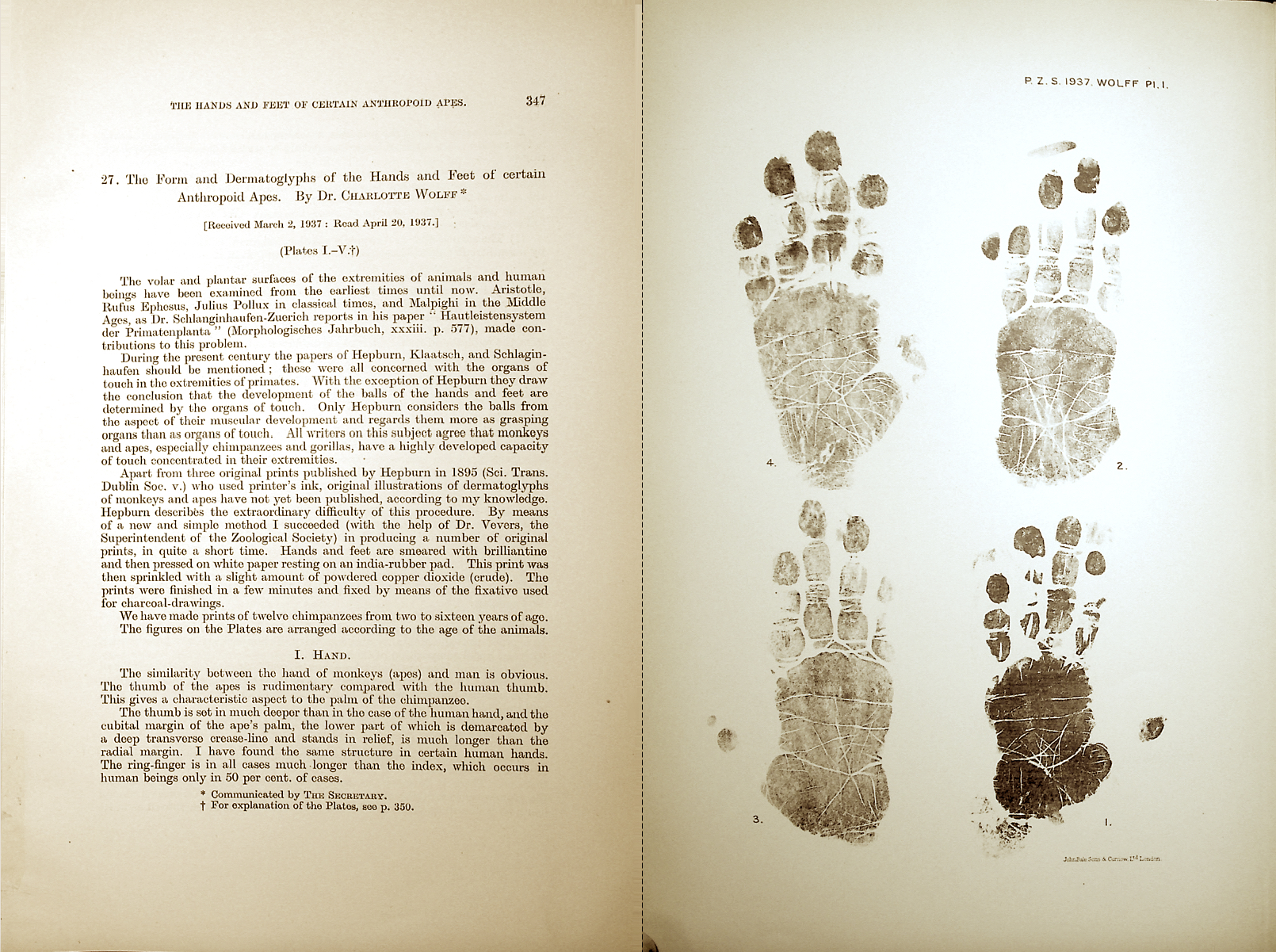

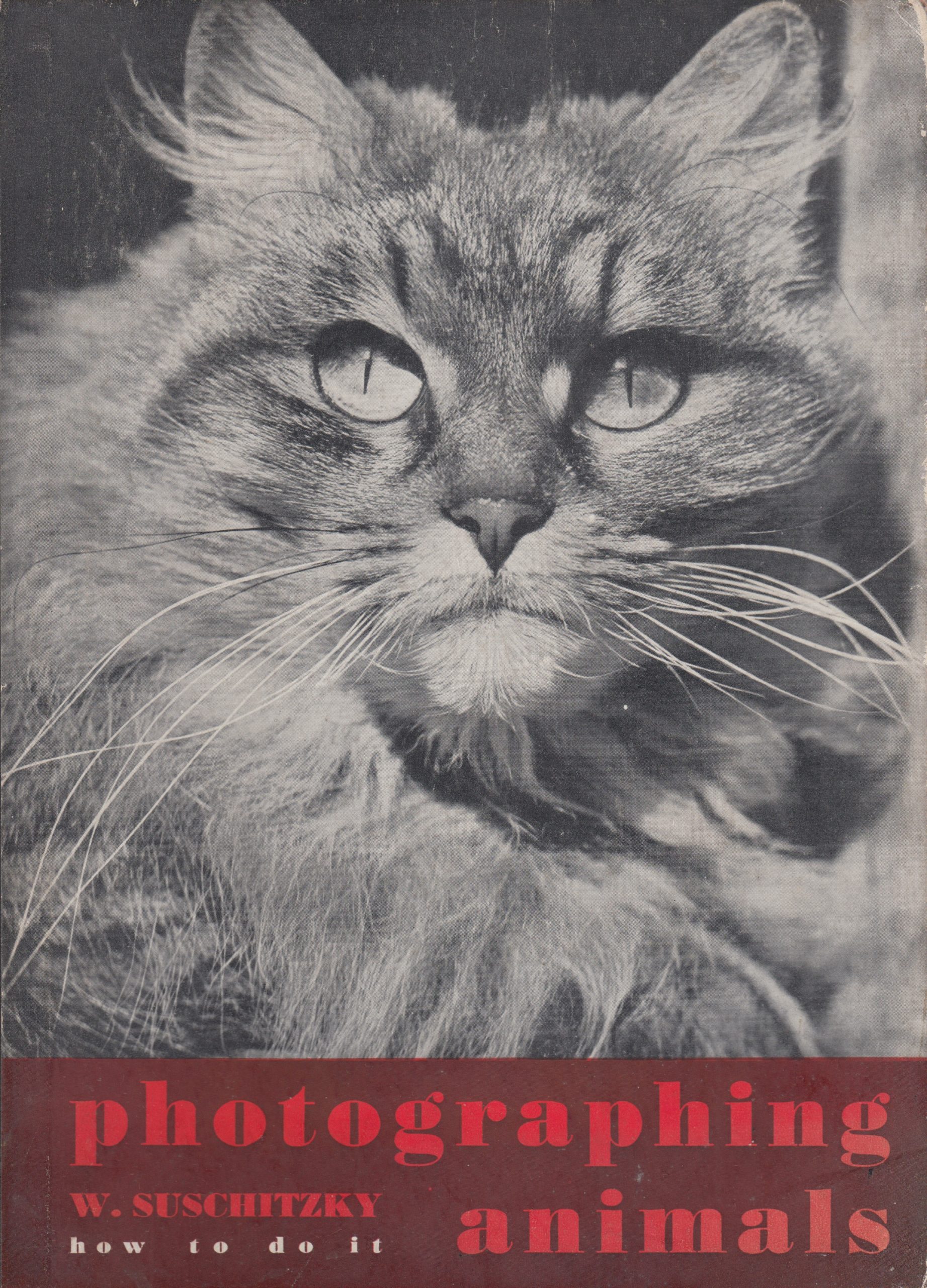

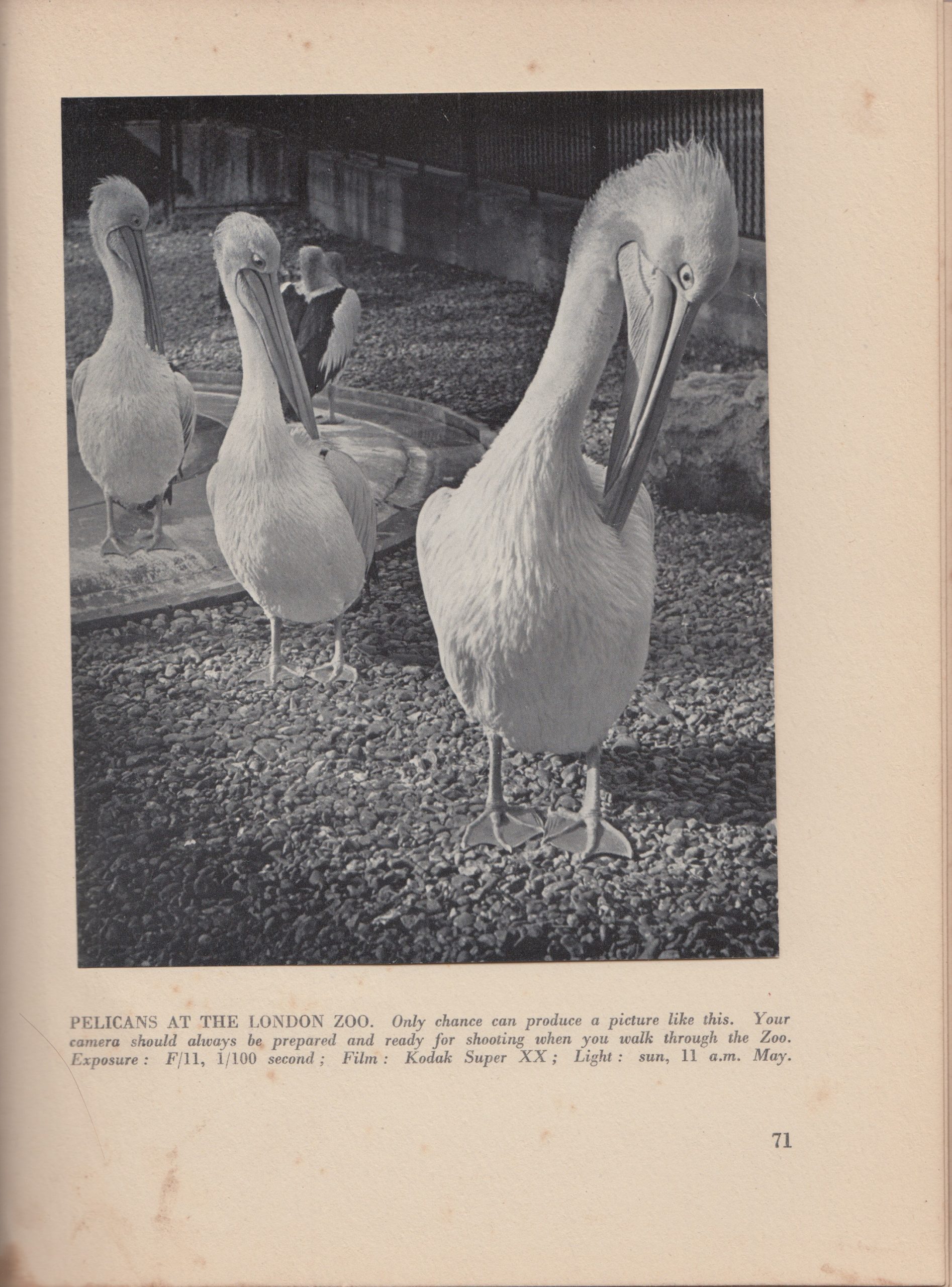

The photographer Wolfgang (Wolf) Suschitzky, who emigrated from Vienna to London, portrayed the animals in London Zoo not with a pen and a brush, but with his camera. Suschitzky made films in and about the zoo as a cameraman, and he received important impulses for his animal photography in Regent’s Park. His photographs articulate an extraordinary understanding of animal photography by placing the animals as models at eye level in the picture. Many of his animal photographs have been reproduced in photo books, guidebooks and magazines. With Huxley, Suschitzky published the successful book Kingdom of the Beasts (1956). The medical doctor Charlotte Wolff had a special relationship with the London Zoo. Originally from Berlin, she had already learned a special skill during her exile in Paris: palm reading. Her research on chirology attracted the attention of the writer Aldous Huxley, and she also came into contact with the Paris Surrealists. In 1936, she published her book Studies in Hand Reading with Chatto & Windus. After she had emigrated to London that same year, Wolff was commissioned by Julian Huxley (brother of Aldous Huxley) to transfer her skills to the apes in the zoo and to read their palms. For this, elaborate impression techniques were used. Charlotte Wolff published her results in two issues of the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London.

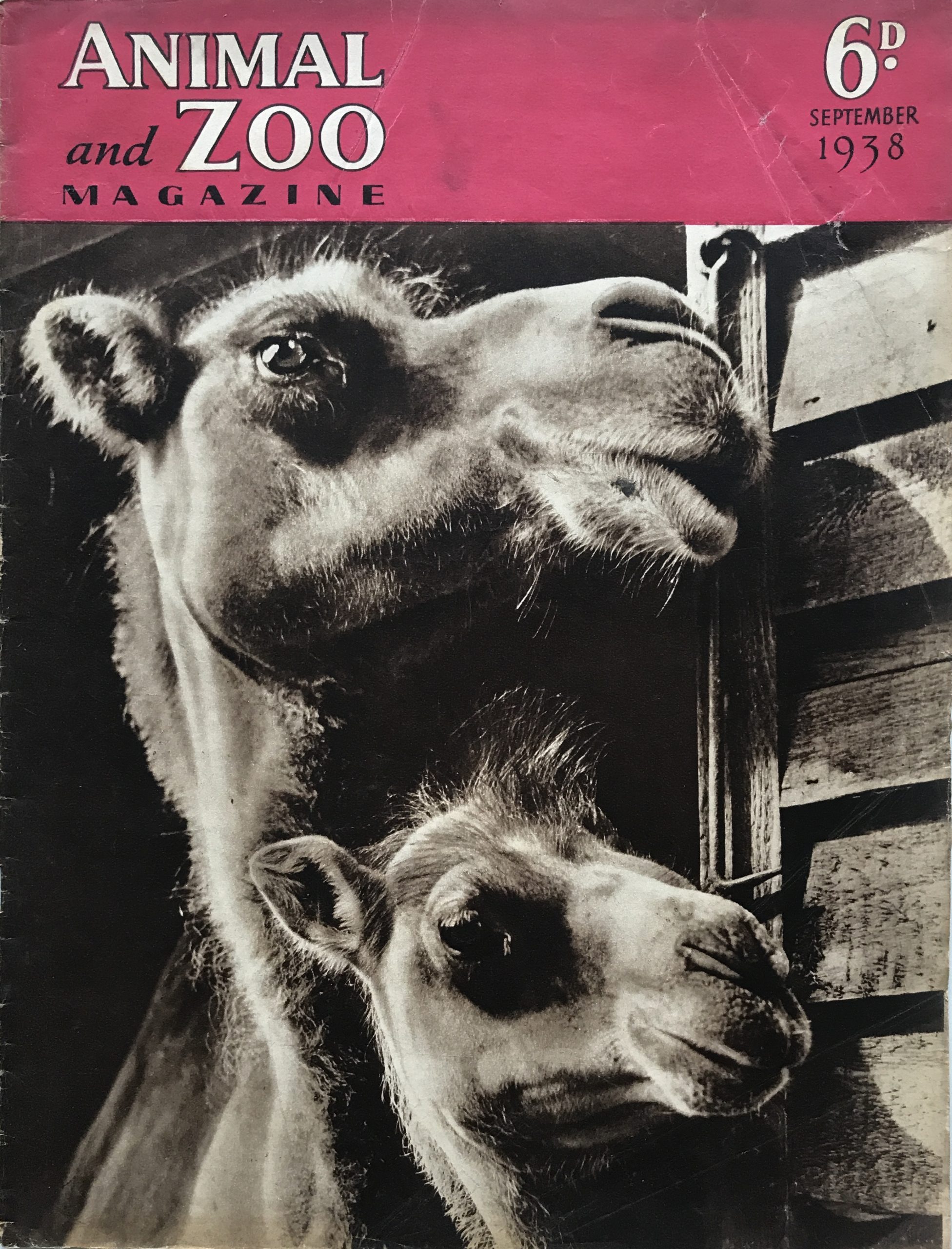

Animal and Zoo Magazine, founded by Julian Huxley, September 1938, cover with a photo by Wolf Suschitzky (© The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

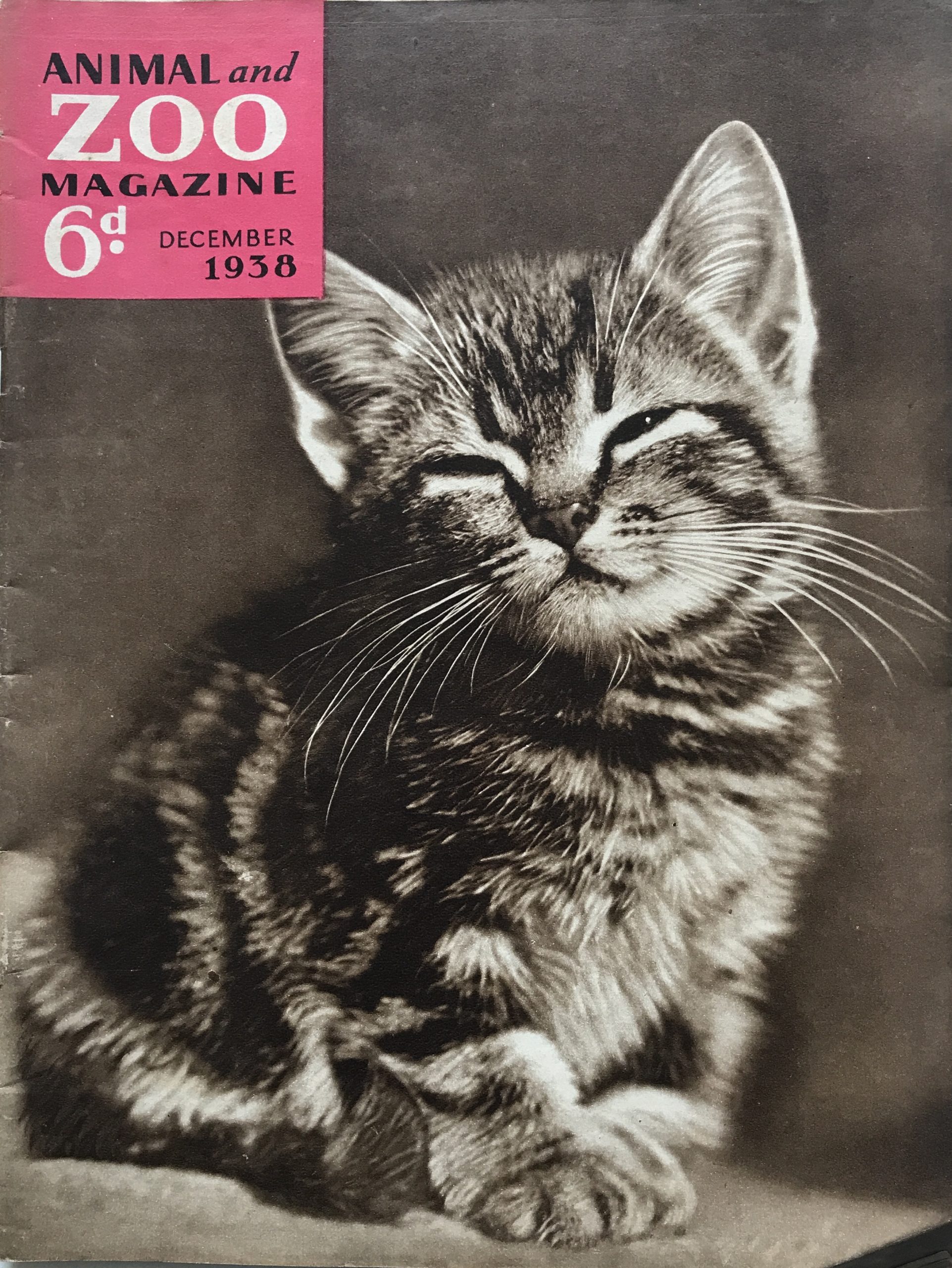

Animal and Zoo Magazine, founded by Julian Huxley, December 1938, with a photo by Wolf Suschitzky (© The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

Wolf Suschitzky (photographs) and Julian Huxley (text). Kingdom of the Beasts. Thames and Hudson, 1956, pp. 157–158 (© The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

Charlotte Wolff. “The Form and Dermatoglyphs of the Hands and Feet of certain Anthropoid Apes”. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, Series A, 1937, Part 3, 347 + Plate (Library of the Zoological Institute, University of Hamburg).

Wolf Suschitzky. Photographing Animals. How to do it. The Studio, 1941. With an Introduction by Julian Huxley (© The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

Wolf Suschitzky. Photographing Animals. How to do it. The Studio, 1941, p. 71 (© The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

07Woburn House/ Upper Woburn Place, Bloomsbury

Due to strict visa regulations, many emigrants were initially unable to take up work and were dependent on financial support, which they applied for at Woburn House in Bloomsbury, where the German-Jewish Aid Committee was based between 1933 and 1938. This was the first port of call for most Jewish refugees from Germany. At Woburn House, help was given with visa applications, but also with finding accommodation. English lessons were offered, and hunger was stilled with the “Free Meal Service”. Woburn House was usually overcrowded with long queues forming in front of the building due to the large number of people seeking help. Sources reveal that the building was visited by 600 to 1,000 people a day.

The Refugee – Today and Tomorrow, Producer: March of Time, Inc., Camera Operator: J.S. Hodgson, 1938, excerpt (Accessed at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives & Records Administration).

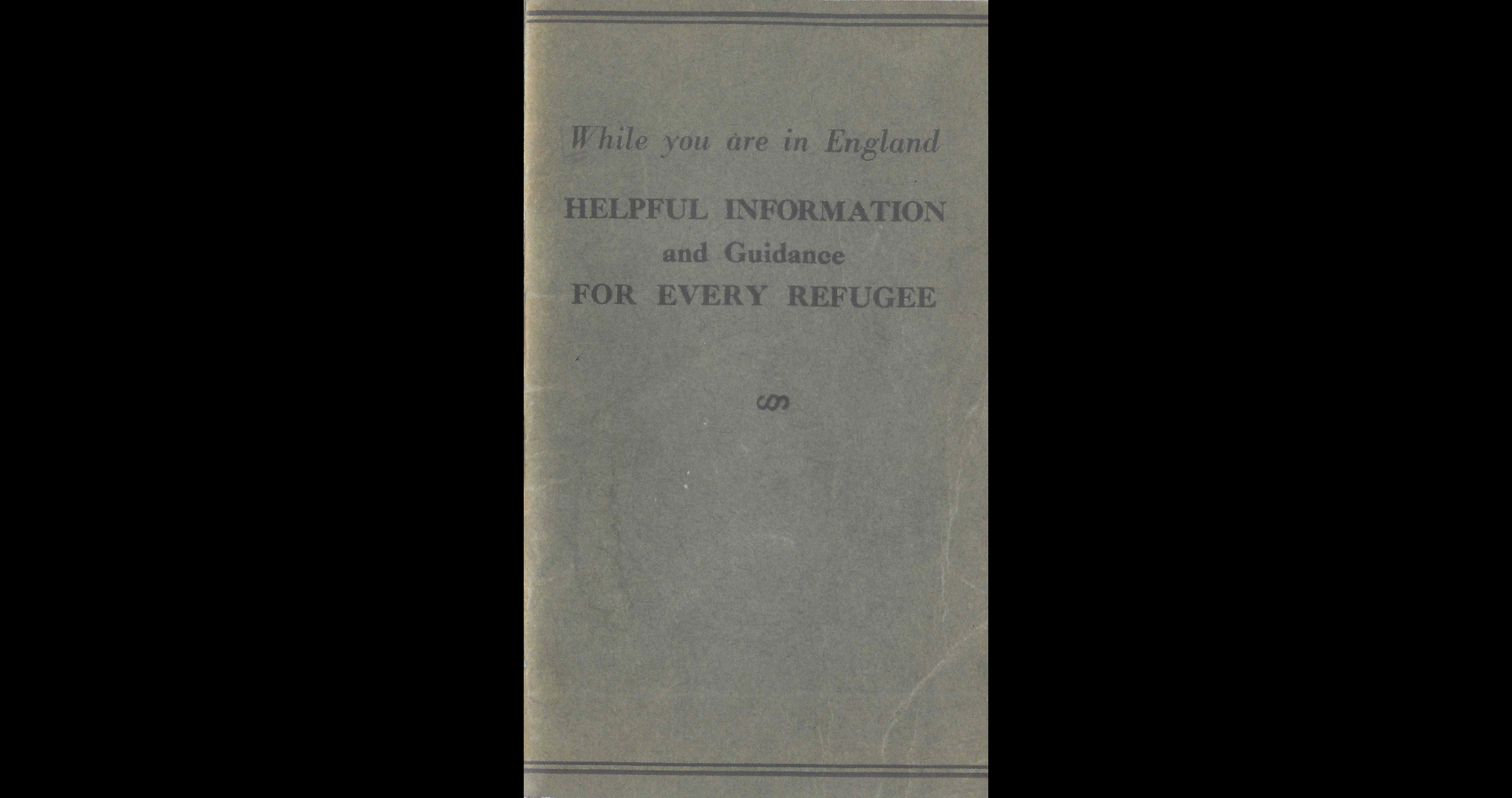

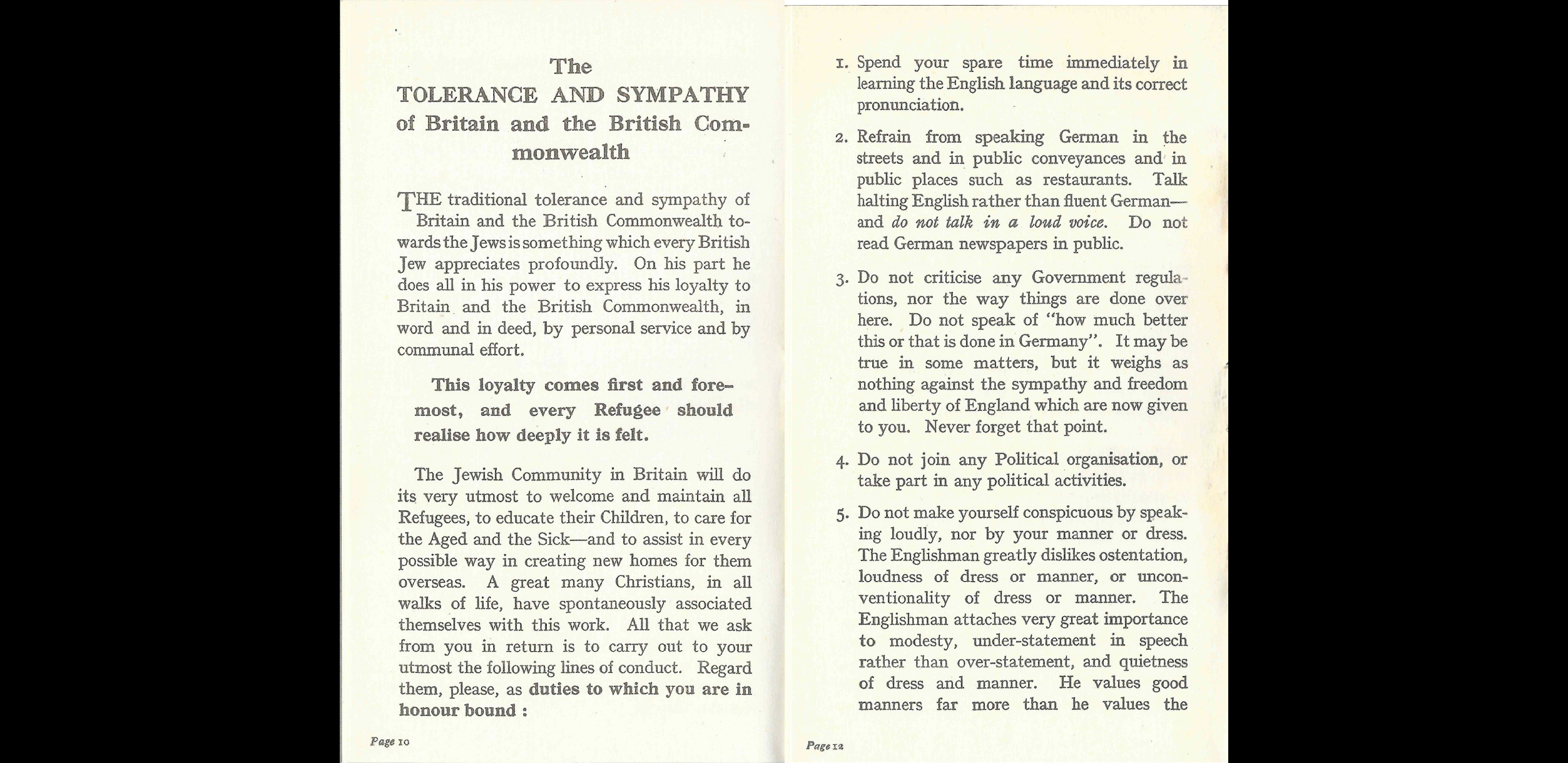

The Jewish Aid Committee published a brochure in German and English for the arriving exiles, intended to provide orientation: the booklet with the tile “While you are in England: Helpful Information and Guidance for Every Refugee” (1938) contained addresses of aid organizations and details on registration procedures and on how to apply for a work permit. Other advice concerned everyday life and basic questions of adaptation to the new environment: for example, information on exemplary behaviour in public places such as not speaking German in public. But the brochure also contained facts for everyday life, such as tables indicating British currency, weight and measurement scale. In 1938 the German-Jewish Aid Committee changed its name to the Jewish Refugee Committee and moved to Bloomsbury House on Bloomsbury Street in Central London.

While you are in England: Helpful Information and Guidance for Every Refugee, 1938, brochure (© Ben Uri Archive).

While you are in England: Helpful Information and Guidance for Every Refugee, 1938, brochure (© Ben Uri Archive).

08Focal Press/ 31 Fitzroy Square, Fitzrovia

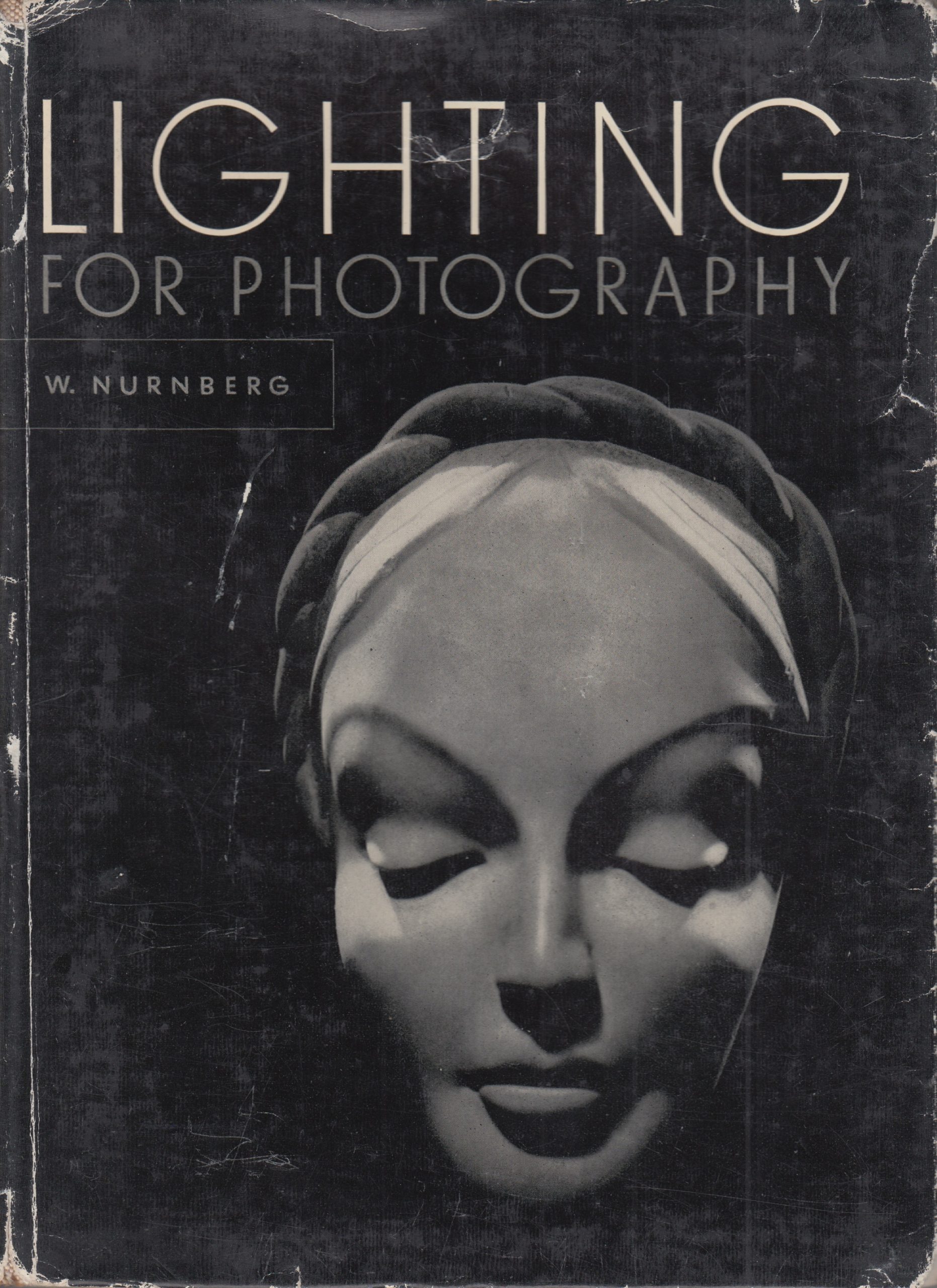

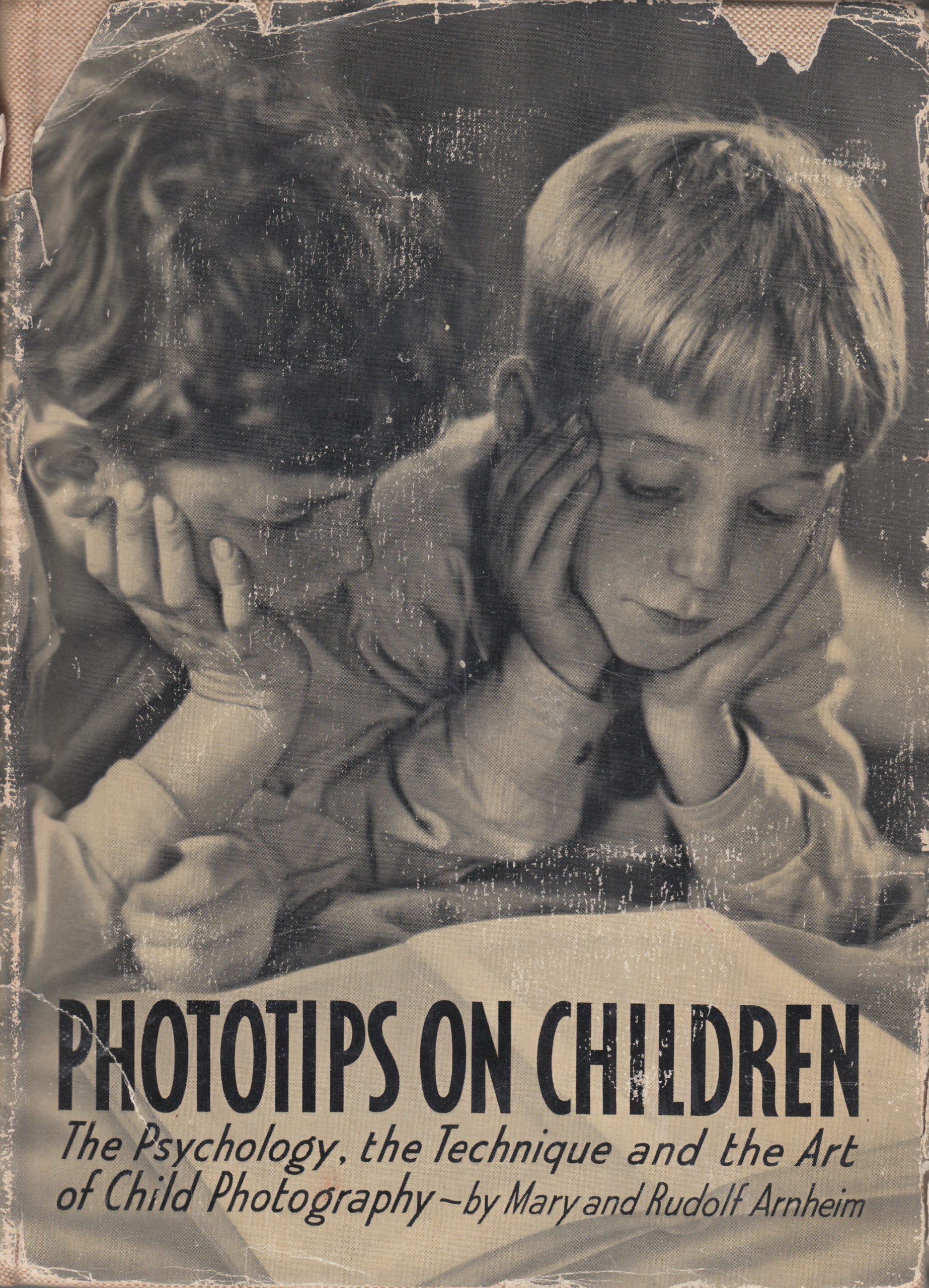

The publishing house Focal Press was founded in 1938 by Andor Kraszna-Krausz. The publisher had emigrated from Berlin to London a year earlier. Focal Press specialised in photo books on the technology, practice and history of photography and successfully published guidebook literature for decades. Between 1938 and 1945 alone, Focal Press published around 140 titles. The publisher taught amateur and professional photographers the techniques of everyday photography. Among Focal Press’s authors were numerous emigrants such as Alex Strasser, Walter Nurnberg, Mary and Rudolf Arnheim and Willy Frerk. focal press was an important contact point for emigrants, and thus also functioned as a platform for their shared interests and a networking hub for emigrated photographers and intellectuals.

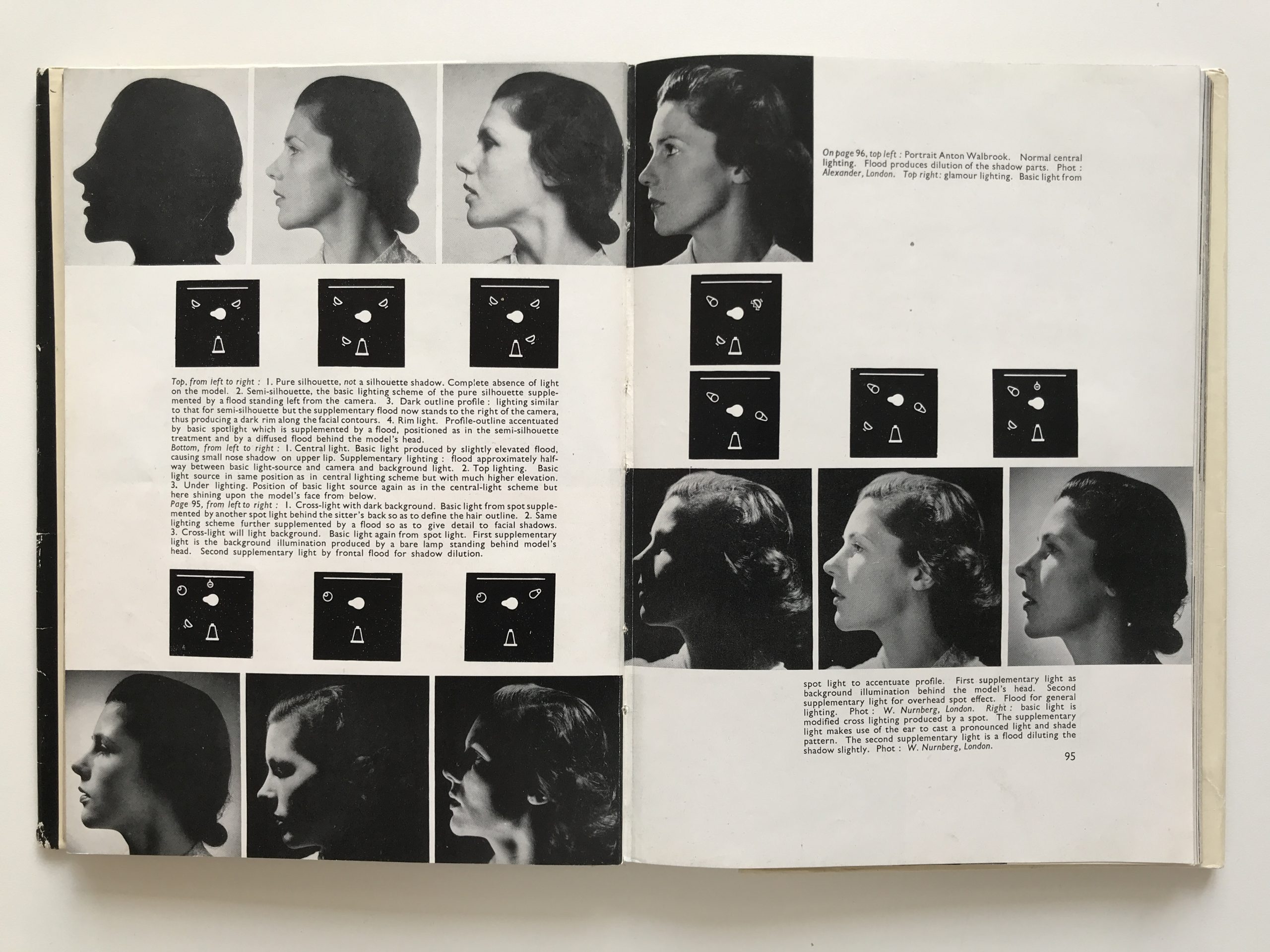

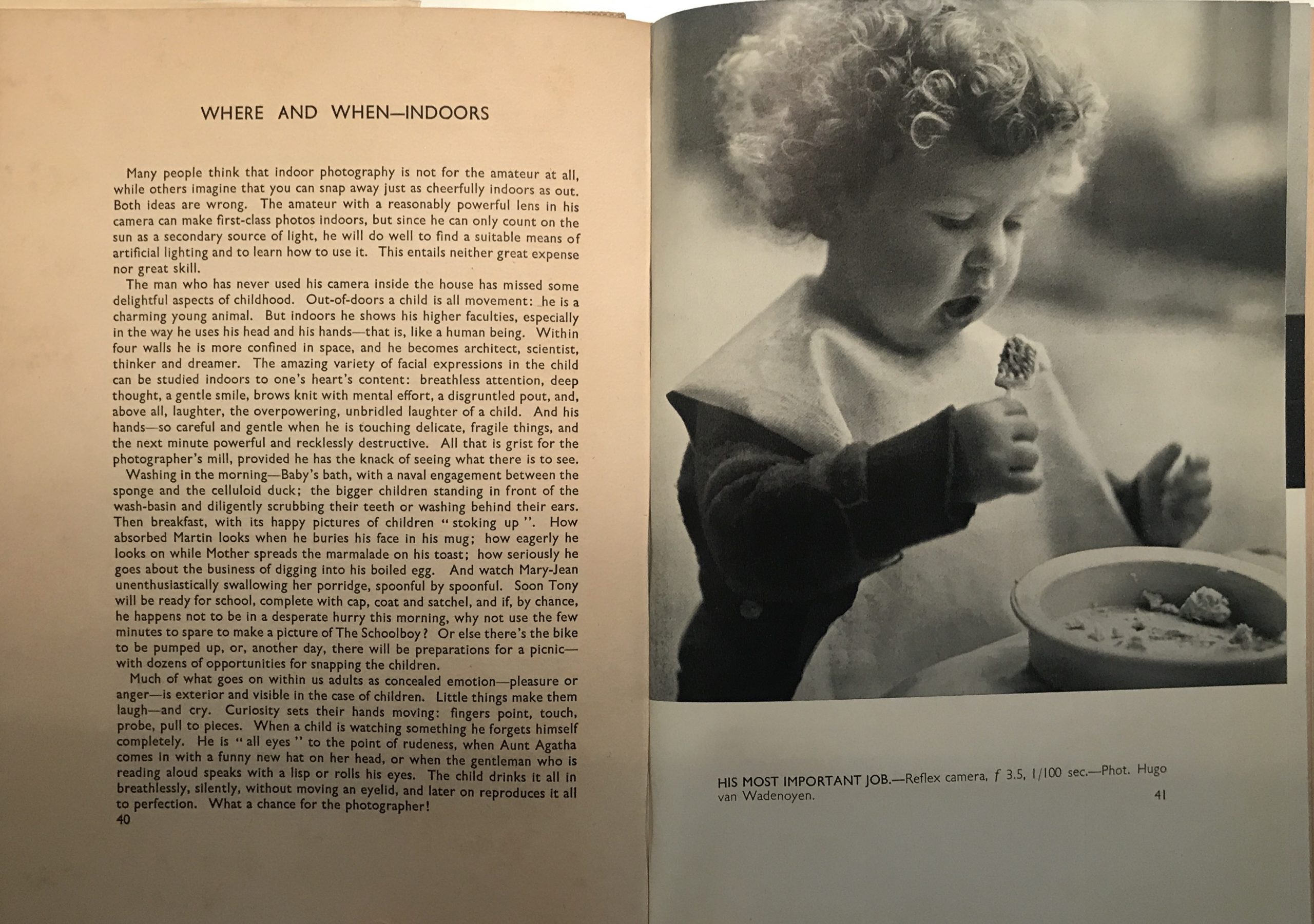

Books by Focal Press, such as W.H. Doering’s Life-like portraiture: with your camera (1938) or Walter Nurnberg’s Lighting for Photography (1940), not only passed on technical knowledge or artistic approaches. They also trained the photographers’ psychological sensitivity: In Mary and Rudolf Arnheim’s Phototips on Children. The Psychology, the Technique and the Art of Child Photography (1939), a different approach to children is demanded through both words and pictures. “Leaving the eye-level” and “descending to the perspective of the children” does not only mean a physical approach but a holistic rethinking and empathy for the needs of the photographed children.

Walter Nurnberg. Lighting for Photography. focal press, 1940, cover (METROMOD Archive).

Walter Nurnberg. Lighting for Photography. Focal Press, 1940, pp. 94–95 (METROMOD Archive).

Mary and Rudolf Arnheim. Phototips on Children. The Psychology, the Technique and the Art of Child Photography. Focal Press, 1939, cover (METROMOD Archive).

Mary and Rudolf Arnheim. Phototips on Children. The Psychology, the Technique and the Art of Child Photography. focal press, 1939, pp. 40–41 with photo by Hugo van Wadenoyen (METROMOD Archive).

Alex Strasser. Victorian Photography. focal press, 1942, title page (METROMOD Archive).

Oliver Pike. Nature and Camera. focal press, 1943, cover (METROMOD Archive).

The Times. British Background. focal press, 1947, cover (METROMOD Archive).

The Times. British Background. focal press, 1947, back cover with logo of focal press (METROMOD Archive).

09Ben Uri Art Gallery/ 14 Portman Street, West End

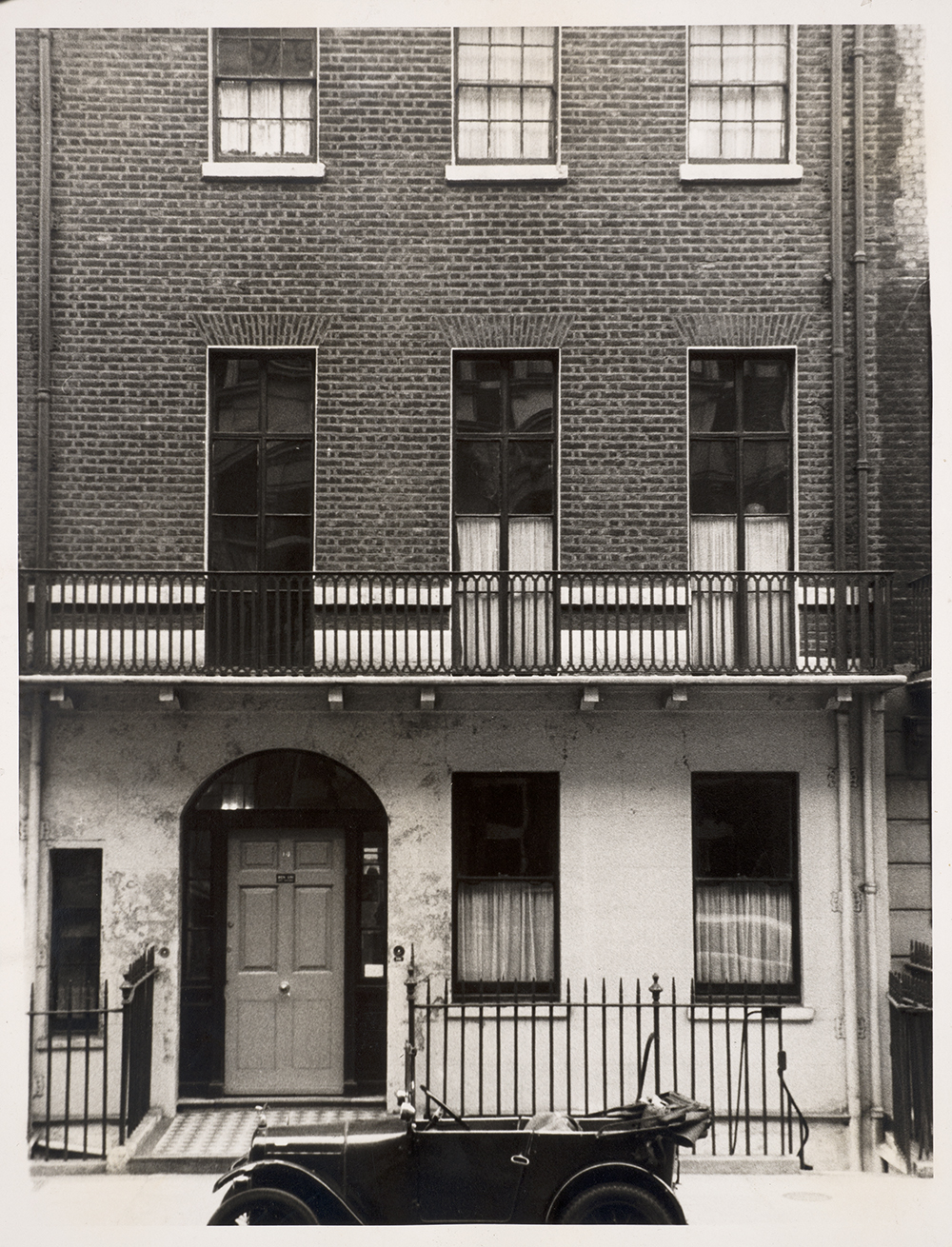

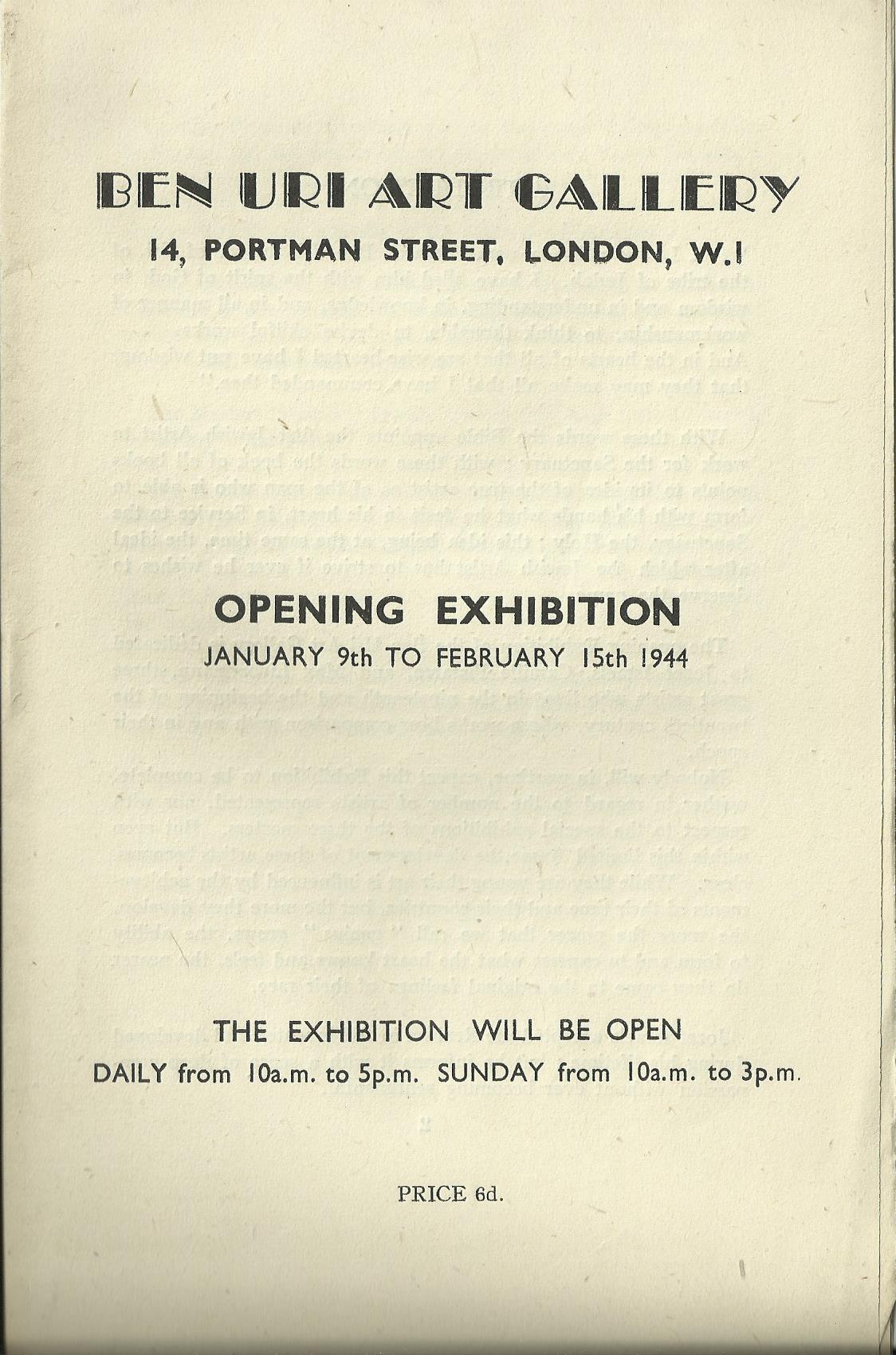

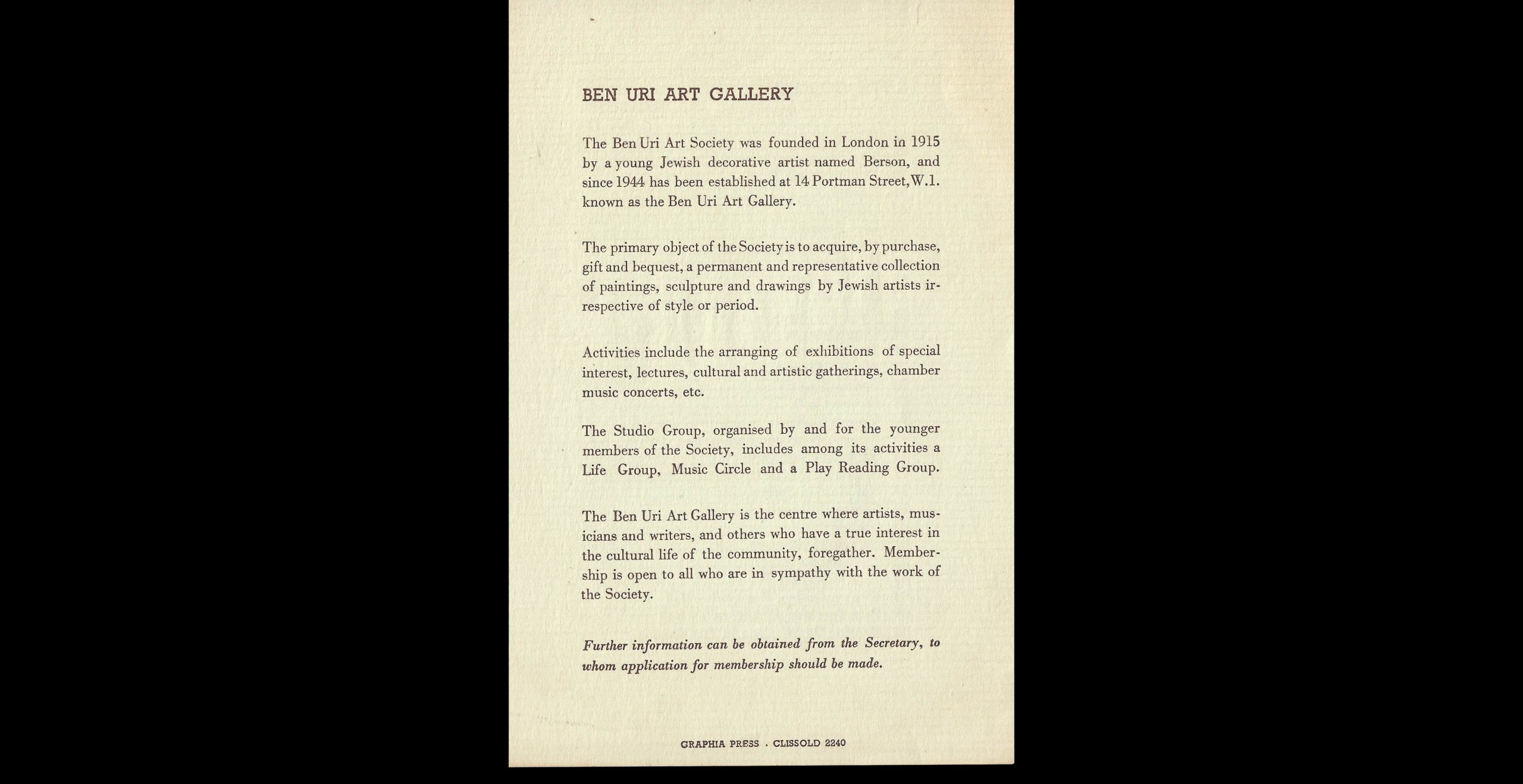

The Ben Uri Art Society was founded in Whitechapel as early as 1915 with the aim of supporting the work of Jewish artists who had migrated to London. After 1933, the Society increasingly opened up to emigrants from the European continent who came to the British capital fleeing National Socialism. However, the Ben Uri Art Society did not yet have its own exhibition space in the 1930s. Only at the beginning of 1944 did it move to a permanent base at 14 Portman Street in the West End, a move that was inaugurated with an opening exhibition. In the following years, the gallery continuously presented group exhibitions, showing works from the gallery’s own collection alongside other works. For many emigrants, the Ben Uri Art Gallery was one of the few places where they could show their art: the opening exhibition of 1944 included works by the émigré artists Jussuf Abbo, Jankel Adler, and Else Fraenkel.

Ben Uri Art Gallery, 14 Portman Street, London W1, Exterior View, 1940s, photographer unknown (© Ben Uri Archive).

Opening Exhibition, Ben Uri Art Gallery, London, 1944, exhibition catalogue (© Ben Uri Archive).

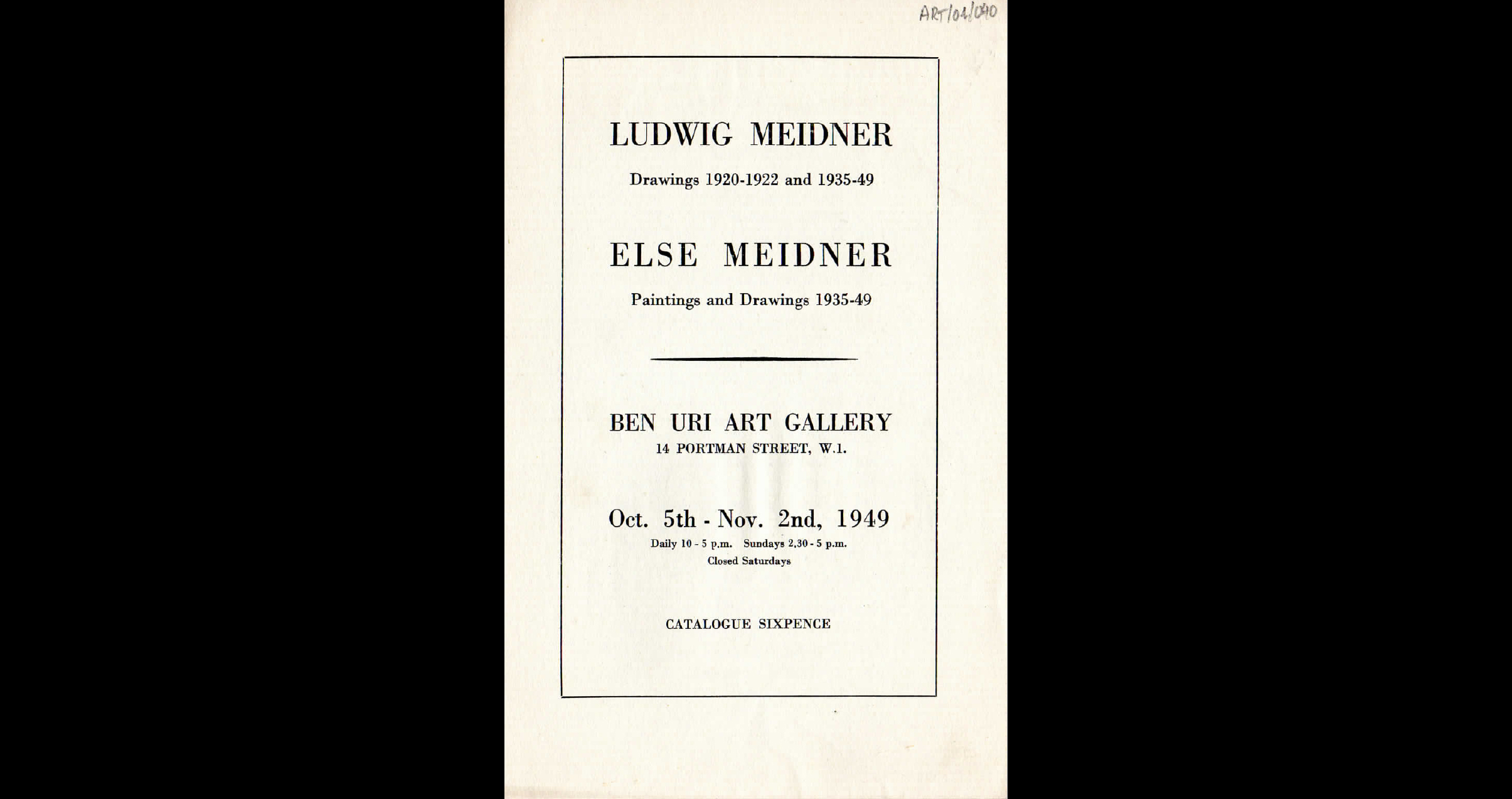

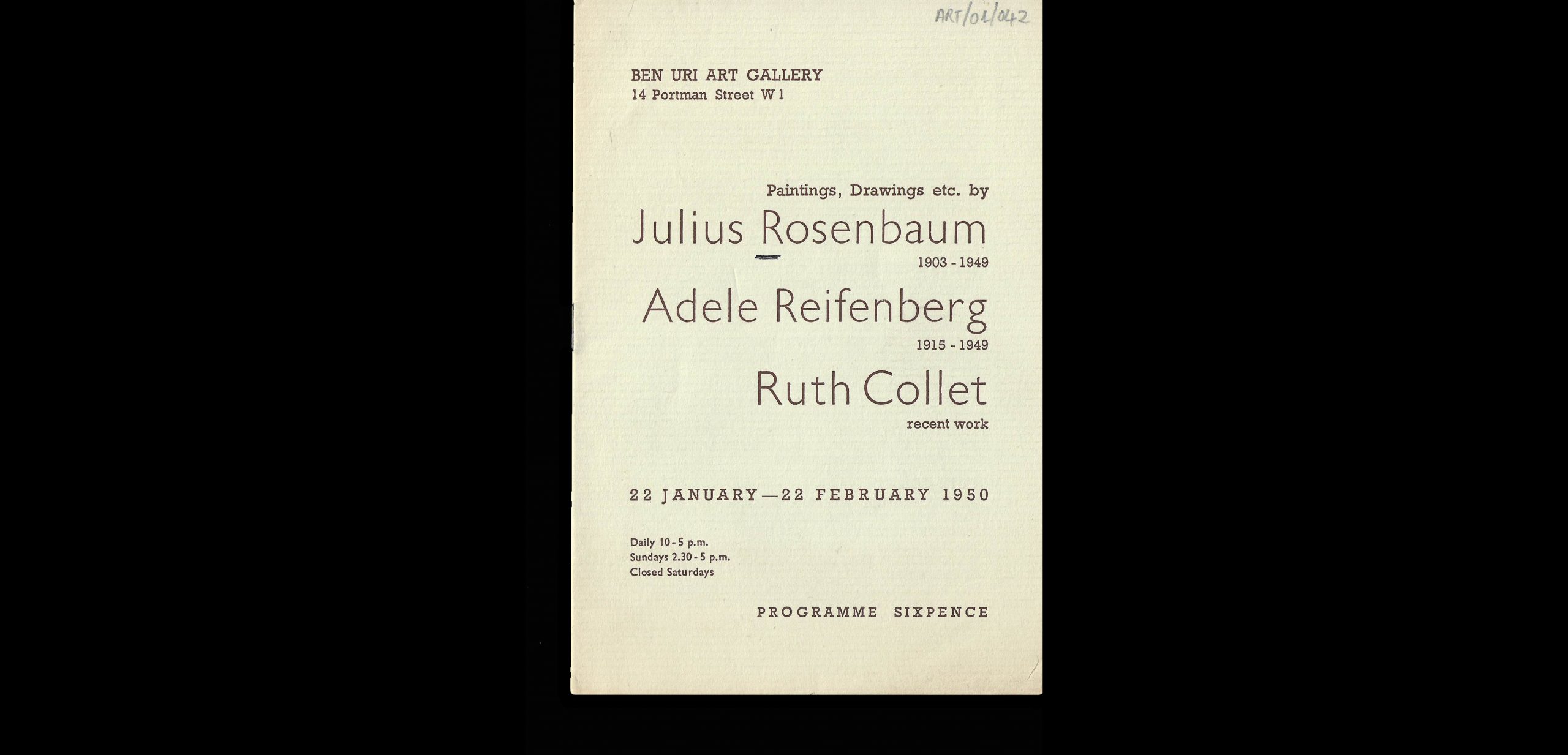

The Ben Uri Art Gallery was also the venue for the very first exhibition of the emigrated artists Ludwig and Else Meidner in 1949 — after a ten-year stay in London. In the same year, the émigré painters Martin Bloch and Josef Hermann also showed their works in a double exhibition. In 1950 the Ben Uri Art Gallery exhibited artworks by the emigrated artists Julius Rosenbaum and Adele Reifenberg together with those of British artist Ruth Collet. Artists were supported not only by exhibitions but also by acquisitions: Jankel Adler’s undated painting Still Life was purchased in 1937; Julius Rosenbaum’s Portrait of Charlotte (1945) entered the collection in 1950. In 1960, the Ben Uri Art Gallery left its former premises and, after several relocations, is now located on Boundary Road.

Ludwig Meidner, Drawings 1920–1922 and 1935–49, Else Meidner, Paintings and Drawings 1935–1949, exhibition catalogue, Ben Uri Art Gallery, 1949 (© Ben Uri Archive).

Paintings, Drawings etc. by Julius Rosenbaum (1903–1949), Adele Reifenberg (1915–1949), and Ruth Collet (recent works), exhibition catalogue, Ben Uri Art Gallery, 1950 (© Ben Uri Archive).

About the Ben Uri Art Gallery in the exhibition catalogue Paintings, Drawings etc. by Julius Rosenbaum (1903–1949), Adele Reifenberg (1915–1949), and Ruth Collet (recent works), 1950 (© Ben Uri Archive).

10Hyde Park/ Marble Arch and Speakers’ Corner, Mayfair

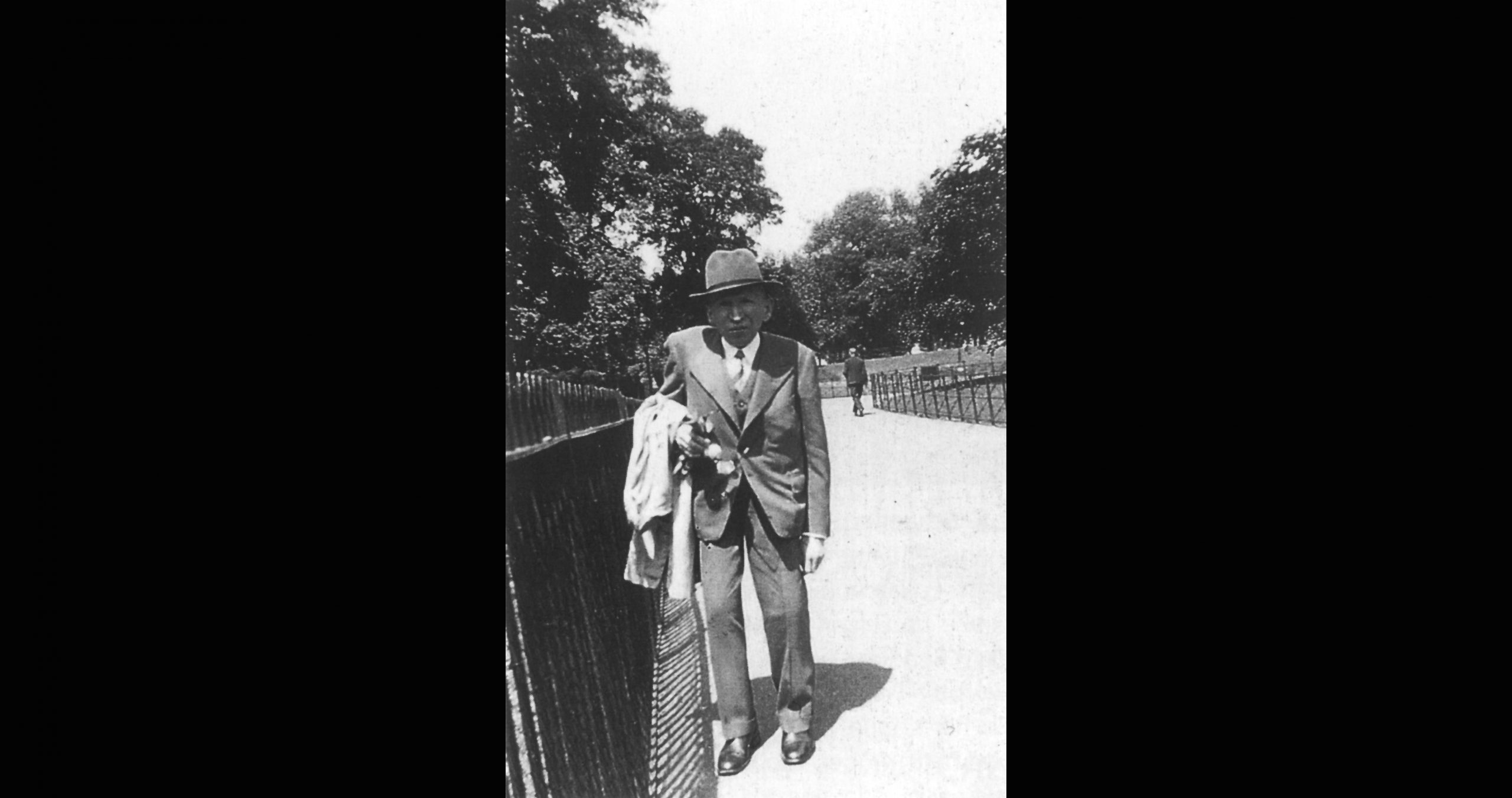

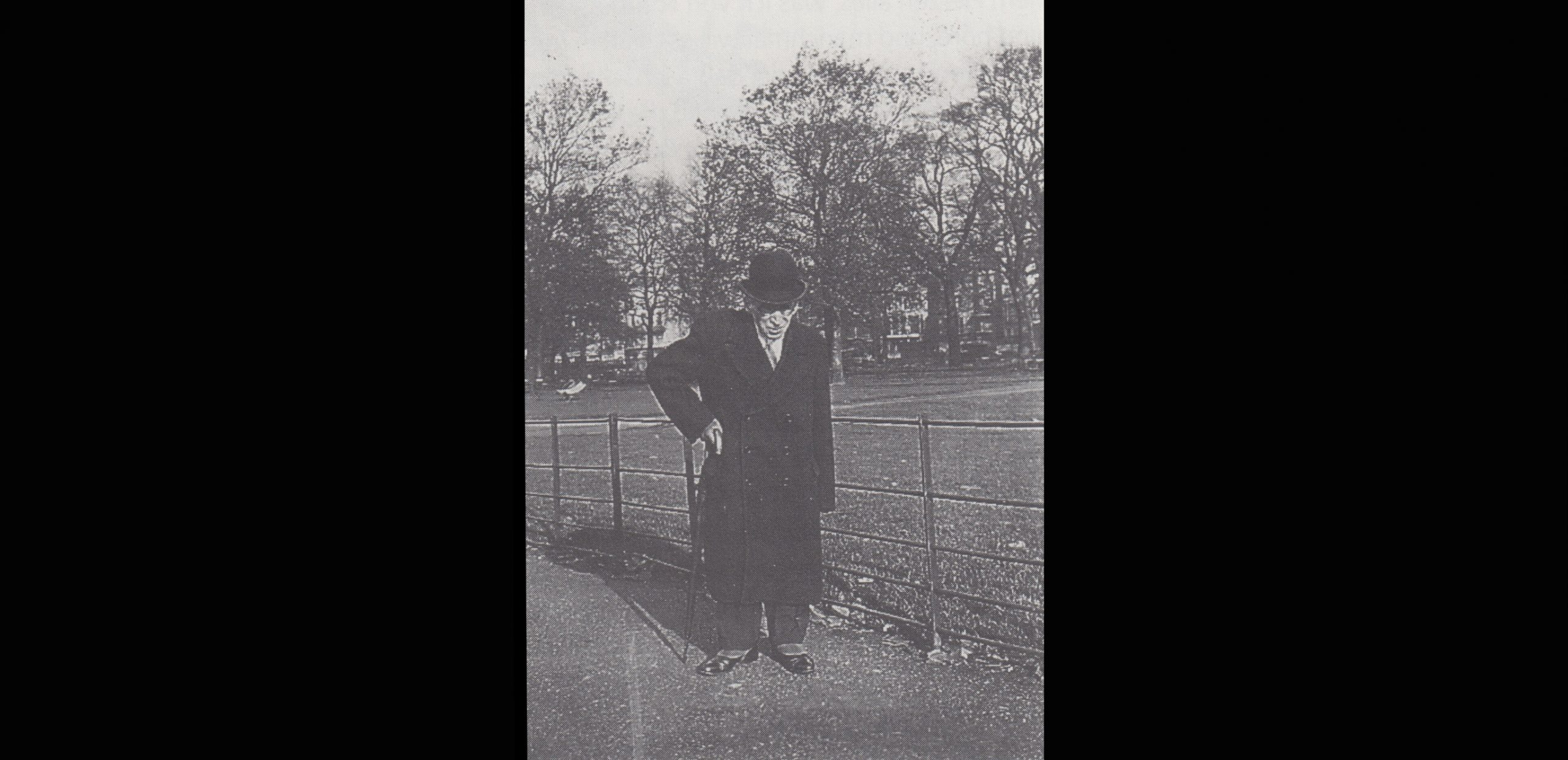

From 1933 on, Max Herrmann-Neisse lived in London together with his wife Leni Herrmann. In the 1920s he had been an acknowledged Berlin poet, whose striking physique was portrayed by numerous artists like George Grosz or Ludwig Meidner. Herrmann-Neisse struggled with his exile in London and expressed this alienation and longing for earlier times in numerous poems. Hyde Park and Regent’s Park became an important reference point. Herrmann-Neisse regularly went for walks here. In his three poems about Hyde Park, Max Herrmann-Neisse writes about longing, the feeling of foreignness and his homesickness. The park functions on many levels: it provides atmosphere, while also constituting a geographical place he may roam through observing; an act which gives comfort, a little confidence, but also inspiration for his poetry. Stefan Zweig writes about his friend’s walks in the park: “For hours he wandered through Hyde Park and Regent’s Park in London, because there, in the midst of the stony wilderness, he found at least a glimpse of the green, a breath of nature, and there he walked as a boy imagines the poet, alone and pensive, sometimes pulling the little notebook out of his pocket and writing down a line, a verse.” (Zweig 1946, 145f.)

Max Herrmann-Neisse during his walks in Hyde Park (Völker 1991, 175f.).

Max Herrmann-Neisse during his walks in Hyde Park (Völker 1991, 175f.).

Max Herrmann-Neisse, “Hyde Park im Schnee”, poem, reading: Simon Zagermann, 2020 (Herrmann-Neiße 1946, 99).

Max Herrmann-Neisse, “Sonntag im Hyde Park”, poem, reading: Simon Zagermann, 2020 (Herrmann-Neiße 1946, 108).

Max Herrmann-Neisse, “Herbst im Hyde Park ”, poem, reading: Simon Zagermann, 2020 (Herrmann-Neiße 1986, 303f.).

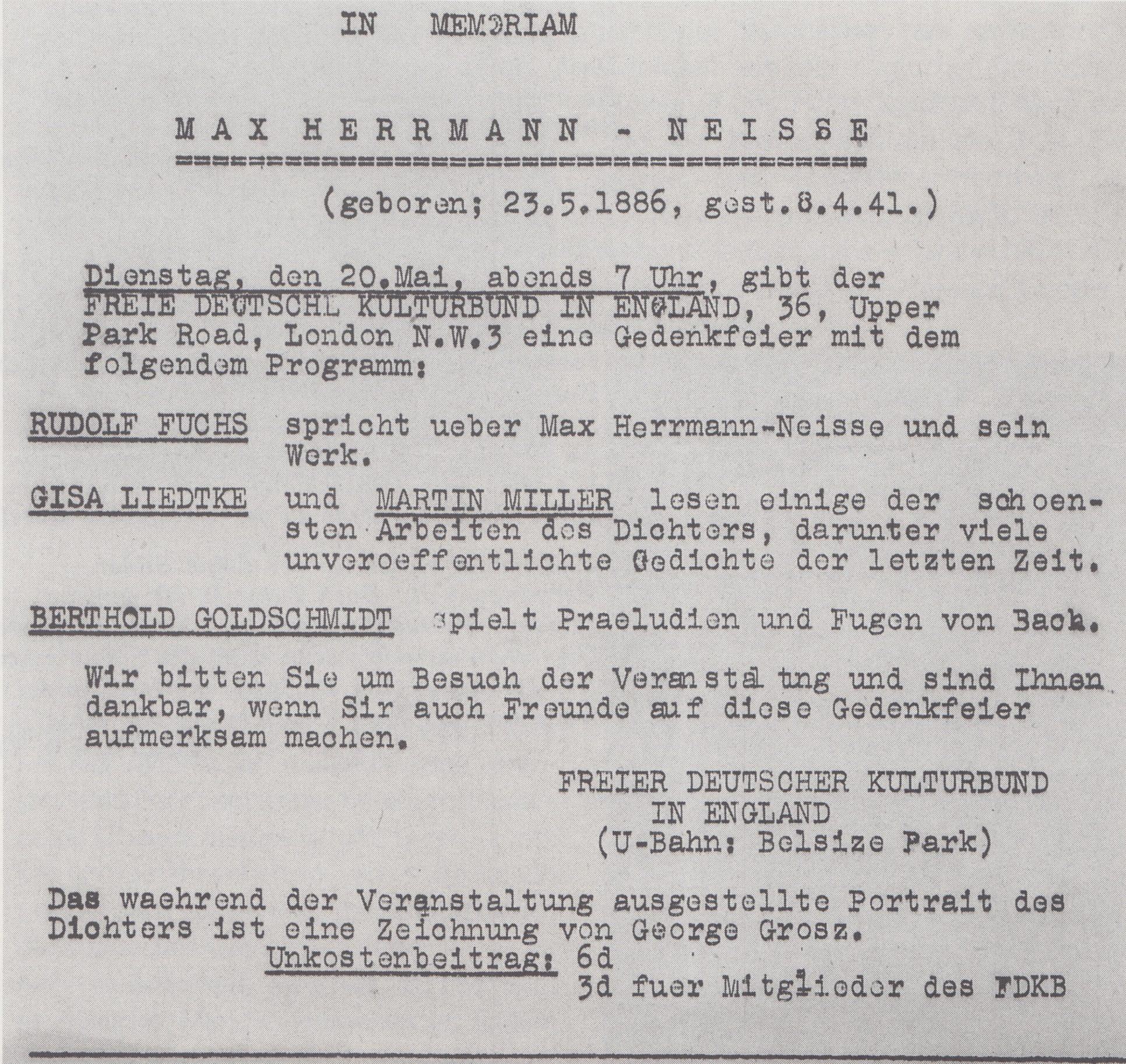

In London, Max Herrmann-Neisse remained productive, devoting his poetry to his exile, and describing his longing for home. Herrmann-Neisse was a co-founder of the German PEN Club in Exile, a section of the international association of PEN (Poets, Essayists, Novelists). Herrmann-Neisse was also active in the Free German League of Culture. He contributed to their anthology Die Vertriebenen (1941). Together with his wife Leni Herrmann and patron Alphonse Sondheimer, Herrmann-Neisse lived in a ménage-à-trois in the newly built Bryanston Court, just seven minutes’ walk from Hyde Park. Here, Herrmann-Neisse experienced the air raids of German planes during the “Blitz” and feared being interned as “enemy alien”. In April 1941, the writer died of heart disease in his flat and was buried at East Finchley Cemetery. One month later the Free German League of Culture dedicated a memorial tribute to him. In 1945 the Aufbau-Verlag Berlin published the poetry collection Heimatfern, followed in 1946 by Erinnerung und Exil (Verlag Oprecht Zurich) with an epilogue by the writer Stefan Zweig, who was also exiled in London.

Die Vertriebenen. Dichtung der Emigration. 37 Poems by Refugee Authors from Austria, Czechoslovakia and Germany, edited by Free German League of Culture, London 1941 (Völker 1991, 235).

Bryanston Court, where Max Herrmann-Neisse lived during his London years from 1936 until his death (Photo: Nana Tigges, 2012).

Grave of Max Herrmann-Neisse at East Finchley Cemetery, London. Photo: 2020 (Photo: Steven Orfao, 2020).

Memorial tribute by the Free German League of Culture for Max Herrmann-Neisse, May 1941 (Völker 1991, 235).

Max Herrmann-Neisse. Erinnerung und Exil. Gedichte. Verlag Oprecht Zurich, 1946 (METROMOD Archive).

Acknowledgements

My deepest thanks go to Sylvia Asmus and Katrin Kokot (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main), Sarah Broadhurst (ZSL Library, London), Bryony Davies (Freud Museum London), Rachel Dickson and Sarah MacDougall (Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, London), Bridget Gillies (University of East Anglia Library, Norwich), Christoph Haacker (Arco Verlag), Frances Kitson, Marion Manheimer, Jacky Oldham, Peter Oldham, Steven Orfao, Peter Suschitzky, Klaus Völker, Julia Winckler, and, last but not least, to Simon Zagermann from Residenztheater (Bayerisches Schauspiel) in Munich for reading the three poems by Max Herrmann-Neisse in a fabulous way.

Bibliography (selection)

llan, John. Berthold Lubetkin. Bauhaus Architecture. Merrell, 2002.

Anonymous. “Plaque: Cosmo Restaurant.” London Remembers. Aiming to capture all memorials in London, https://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/cosmo-restaurant. Accessed 23 September 2020.

Benton, Tim. The Modernist Home. V & A Publishing, 2006.

Bihler, Lori Gemeiner. Cities of Refuge: German Jews in London and New York, 1935–1945. SUNY Press, 2018.

Bohm-Duchen, Monica, editor. Insiders Outsiders. Refugees from Nazi Europa and their Contribution to British Visual Culture. Lund Humphries, 2019.

Brinson, Charmian, and Richard Dove, editors. Politics By Other Means. The Free German League of Culture in London 1939–1946. Vallentine Mitchell, 2010.

Carr, Richard. “Lawn Road Flats.” 17 June 2004, studio international, https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/lawn-road-flats. Accessed 28 October 2020.

Daybelge, Leyla, and Magnus Englund. Isokon and the Bauhaus in Britain. Batsford, 2019.

Dickson, Rachel, and Sarah MacDougall. “Mapping Finchleystrasse: Mitteleuropa in North West London.” Arrival Cities. Migrating Artists and New Metropolitan Topographies in the 20th Century, edited by Burcu Dogramaci et al., Leuven University Press, 2020, pp. 229–248.

Dorner, Jane. “Andor Kraszna-Krausz: Pioneering Publisher in Photography.” Immigrant Publishers. The Impact of Expatriate Publishers in Britain and America in the 20th Century, edited by Richard Abel and Gordon Graham, Routledge, 2009, pp. 99–110.

Forbes, Duncan. “Wolf Suschitzky in Vienna and London. Photographic Exchange and Continuity.” Wolf Suschitzky Photos, edited by Michael Omasta et al., Synema, 2006, pp. 16–29.

Forrester, John. “Freudsches Sammeln.” „Meine … alten und dreckigen Götter“. Aus Sigmund Freuds Sammlung, edited by Lydia Marinelli, exh. cat. Sigmund Freud-Museum, Vienna, 1998, pp. 21–35.

Gay, Peter. Freud. Eine Biographie für unsere Zeit. S. Fischer Verlag, 1989.

Herman, Judi. “The Cosmo comes to life again.” 2 November 2019, Jewish Renaissance, https://www.jewishrenaissance.org.uk/blog/the-cosmo-comes-to-life-again. Accessed 23 September 2020.

Herrmann-Neiße, Max. Gesammelte Werke, Gedichte, Vol. 2: Um uns die Fremde, edited by Klaus Völker, Zweitausendundeins, 1986.

Herrmann-Neiße, Max and Leni Herrmann. Liebesgemeinschaft in der Fremde. Gedichte und Aufzeichnungen, edited by Christoph Haacker, Arco, 2012.

Ich reise durch die Welt. Die Zeichnerin und Publizistin Erna Pinner (Schriftenreihe Verein August Macke Haus Bonn, 23), exh. cat. Verein August Macke Haus, Bonn, 1997.

Major, Máté. Goldfinger Ernö. Akadémai Kiadó, 1973.

Müller-Härlin, Anna. “The Artist’s Section.” Politics By Other Means. The Free German League of Culture in London 1939–1946, edited by Charmian Brinson and Richard Dove, Vallentine Mitchell, 2010, pp. 54–73.

Newton, Miranda H. Architect’s London Houses. The Homes of Thirty Architects since the 1930s. Butterworth, 1992.

Out of Chaos. Ben Uri: 100 Years in London, edited by Rachel Dickson and Sarah MacDougall, exh. cat. Ben Uri, London, 2015.

Pross, Steffen. “In London treffen wir uns wieder“. Vier Spaziergänge durch ein vergessenes Kapitel deutscher Kulturgeschichte nach 1933. Eichhorn, 2000.

Rappold, Claudia. Charlotte Wolff (1897–1986): Ärztin, Psychotherapeutin, Wissenschaftlerin und Schriftstellerin. Hentrich und Hentrich, 2005.

Saunders, Doug. Arrival City. How the Largest Migration in History is Reshaping Our World. William Heinemann, 2010.

Schur, Max. Sigmund Freud. Leben und Sterben. Suhrkamp, 1982.

Vinzent, Jutta. Identity and Image. Refugee Artists from Nazi Germany in Britain (1933–1945) (Schriften der Guernica-Gesellschaft, 16). VDG, 2006.

Völker, Klaus. Max Herrmann-Neiße: Künstler, Kneipen, Kabaretts – Schlesien, Berlin, im Exil. Edition Hentrich, 1991.

Warburton, Nigel. Ernö Goldfinger. The Life of an Architect. Routledge, 2003.

Welter, Volker M. Ernst L. Freud, Architect: The Case of the Modern Bourgeois Home. Berghahn, 2012.

Winckler, Julia. “Gespräch mit Wolfgang Suschitzky, Fotograf und Kameramann, London 2001/2002.“ Exilforschung. Ein internationales Jahrbuch, Vol. 21: Film und Fotografie, edited by Claus Dieter-Krohn et al., edition text + kritik, 2003, pp. 254–279.

Winckler, Julia. “‘Quite content to be called a good craftsman’ – an Exploration of some of Wolf Suschitzky’s Extensive Contributions to the Field of Applied Photography between 1935 and 1955.” Applied Arts in British Exile from 1933. Changing Visual and Material Culture (The Yearbook of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, 19, 2018), edited by Marian Malet et al., Brill/Rodopi, 2019, pp. 67–92.

Wolff, Charlotte. Augenblicke verändern uns mehr als die Zeit. Eine Autobiographie. Translated by Michaela Huber, Beltz, 1982.

Wright, Paul. “Finchley Road restaurant remembered as ‘saviour’ for Jews fleeing fascism.” 30 November 2013, Ham & High, https://www.hamhigh.co.uk/news/finchley-road-restaurant-remembered-as-saviour-for-jews-fleeing-fascism-1-3047713. Accessed 2 January 2021.

Zweig, Stefan. “Max Herrmann-Neiße zum Gedächtnis.” Max Herrmann-Neisse. Erinnerung und Exil. Gedichte. Verlag Oprecht, 1946, pp. 145–147.

Zwerger, Veronika, and Ursula Seeber, editors. Küche der Erinnerung. Essen & Exil. new academic press, 2018.