Istanbul

A Walk Through the Russian “Montparnasse” in Istanbul

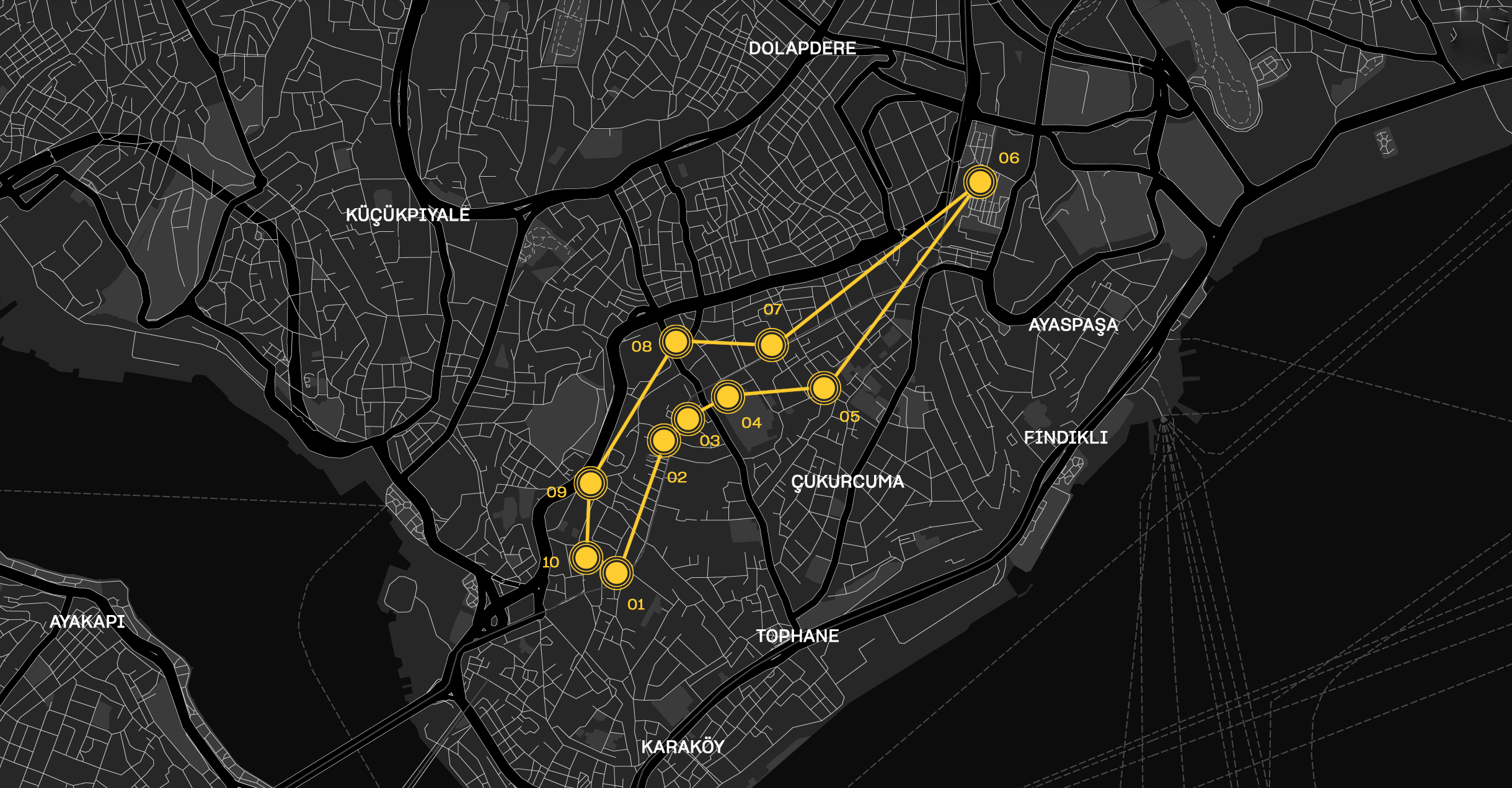

For Russian-speaking émigrés who fled abroad after the 1917 Revolution, one of the most important destinations and, in many cases, the first stop on a long émigré journey, was Istanbul. The Beyoğlu district, formerly called Pera, became an artistic, creative space that had a lot in common with the Russian artist enclave in Montparnasse, the district on the left bank of the Seine in Paris. Beyoğlu, with its interesting and rich past, has seen many artists in its lifetime, and this was one of the deciding factors for Russian newcomers involved in the art world (it is important to note that not all émigrés were Russian, but all of them came from the Russian Empire). This walk will introduce a number of Beyoğlu locations that became key sites for painters, sculptors and photographers. Among them you will find multiple residences, institutions and contact zones.

miles 90

min. 10

sights Foot

01Tünel Square/ Tünel Meydanı, Beyoğlu

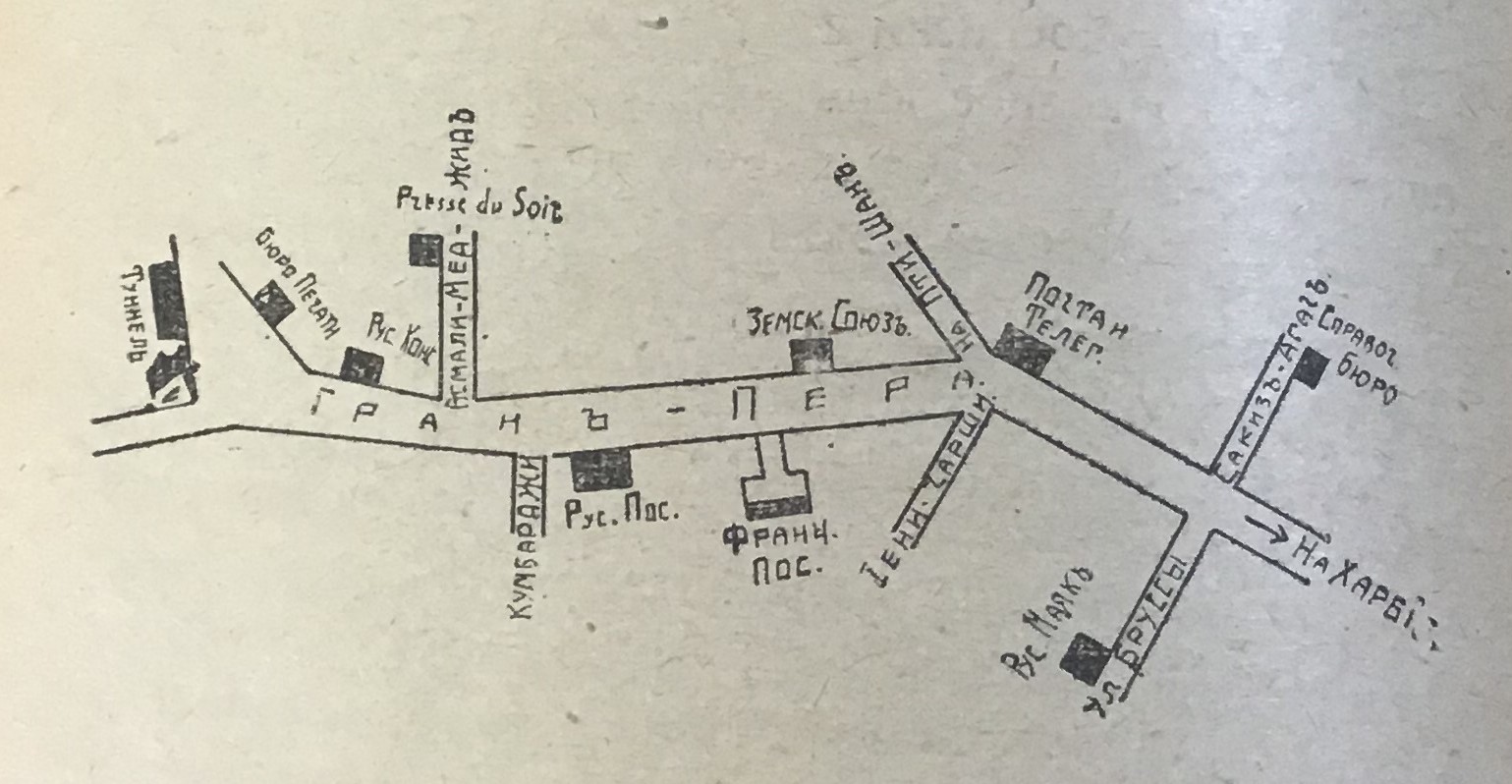

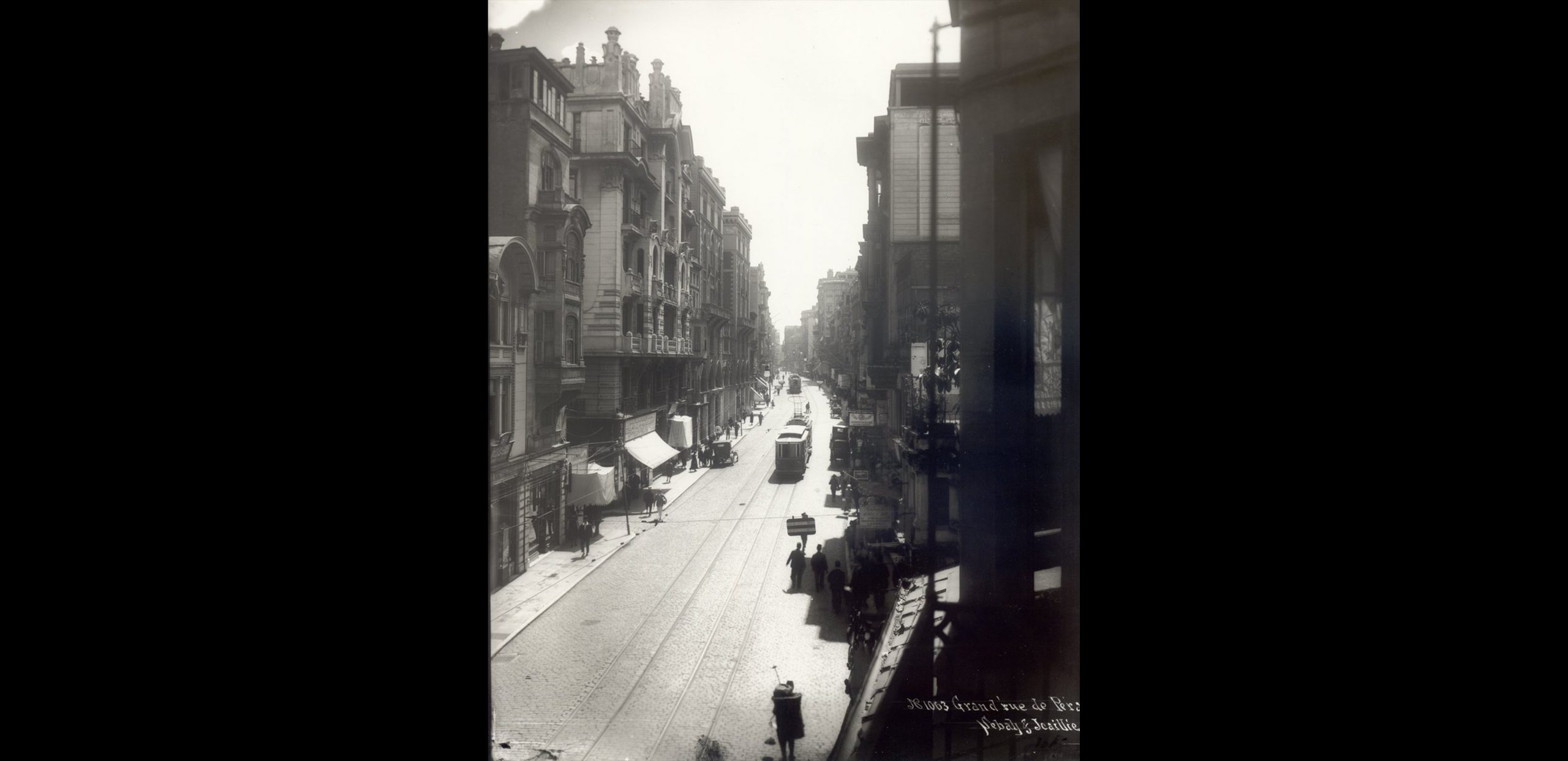

The walk begins at Tünel Square, the final destination of the one-stop funicular railway from Karaköy. For a traveller coming from the Karaköy or Galata quarters, this square constituted the starting point of a long, noisy and famous street, the Grand Rue de Péra, now called İstiklal. In the early 1920s, Russian life in this tiny square was in full swing, largely because Tünel Square was (and still is) located in close vicinity to the neo-Renaissance building of the Russian Embassy (now Consulate, İstiklal Caddesi 219). Russian signs were everywhere. At the time, the square featured not only the Russian newsstand, but also the editorial office of the weekly periodic publication Zarnitsy (Tünel Meydanı Sk. 2/B), where Vladimir Kadulin (Владимир Кадулин, 1884–1957) worked as a cartoonist under the pen-name Nayadin (Наядин). During his time at Zarnitsy, Kadulin created many caricatures and designed almost all covers of the periodical. Most of his works were devoted to the difficult life of Russian émigrés abroad and made a mockery of the Bolsheviks. It is worth noting that at that time many artists and photographers worked for the local Russian newspapers (by producing illustrations, caricatures or photographs), as it was a good opportunity to earn some money – among other reasons of course.

Layout of the Grand Rue de Péra (Istiklal Street) from the Istanbul Guide for Russian refugees in Russian language, 1921.

Station du Tunnel à Péra – Tunnel Station in Pera, 1884. Creator: Basile Kargopoulo (SALT Araştırma, Fotoğraf ve Kartpostal Arşivi, Istanbul).

İstanbul Rus Konsolosluğu – Russian Consulate (SALT Araştırma, Fotoğraf ve Kartpostal Arşivi, Istanbul).

Tünel Geçidi İş Hanı – Tunnel Passage Office Building, around 1920 (SALT Araştırma, Fotoğraf ve Kartpostal Arşivi, Istanbul). On closer inspection of the picture, one can easily see and read the Russian sign “Bureau of the Russian Press”.

02Jules Kanzler Photo Studio/ Istiklal Caddesi 150, Beyoğlu

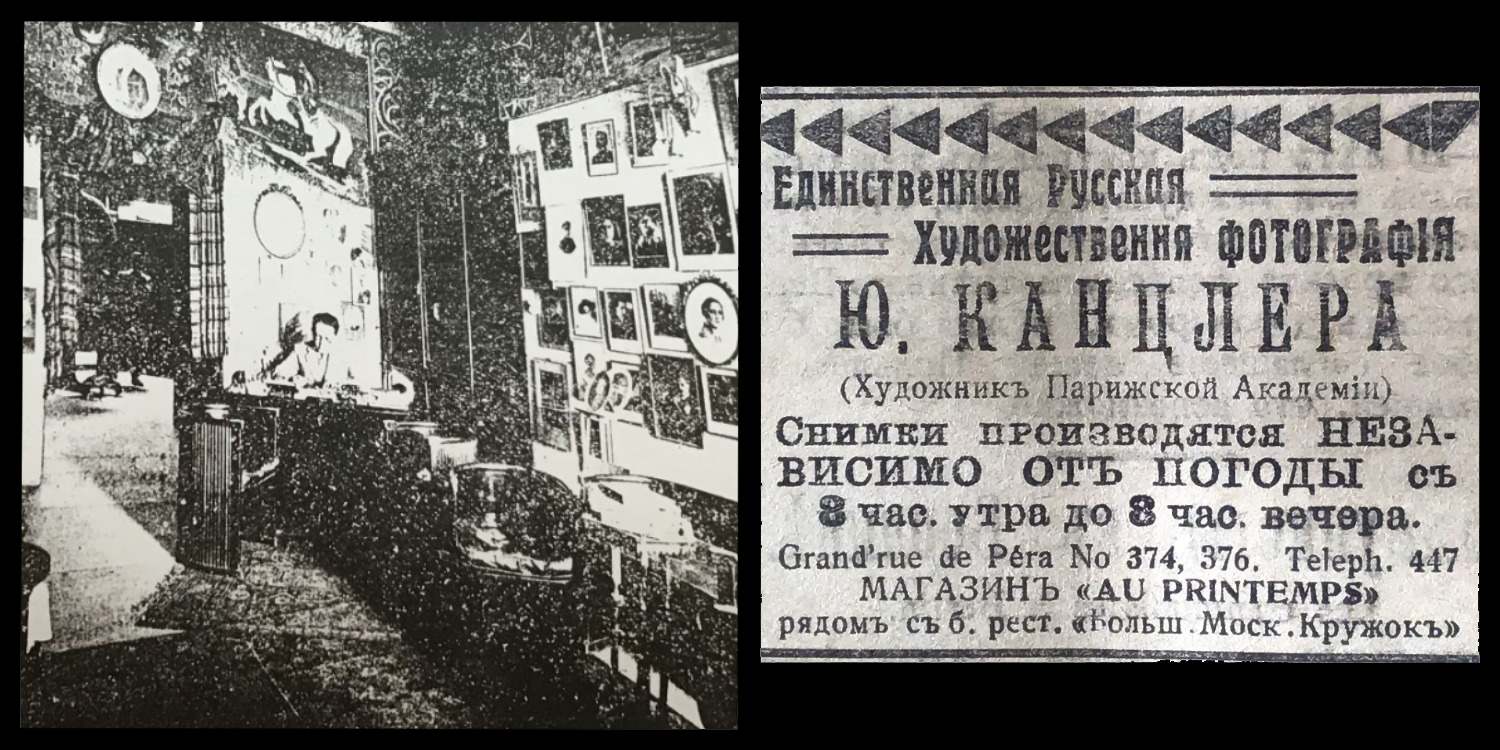

On the same street, next to the Russian Embassy, you could find Jules Kanzler’s (Жюль Канцлер) photo studio. Part of his life was spent in Crimea and Odessa where he worked as a painter, the other part of his life he spent in Turkey as an émigré photographer. Eventually, he decided to stay and become a Turkish citizen. The photo studio was located at Grand Rue de Péra 374/376, which, according to the Goad maps, corresponds to today’s Istiklal Caddesi 150. It had been there for quite a while, with an entrance via the store Au Printemps, before it moved to the very top of the street, close to Taksim Square. Judging by the only photograph of his studio, published in the almanac Les Russes sur le Bosphore, it was a cosy place with antique furniture. On the walls of the studio one could see not only portrait photographs, but also works by different painters. We know, for instance, that the studio sold works by the famous Russian painter Leonid Sologub (Леонид Сологуб, 1884–1956), who after the revolution lived in Istanbul for a short while and later settled in the Netherlands. Muhsin Ertuğrul, an important contributor to both Turkish theatre and Turkish cinema, contacted the Russian émigré painter Nikolai Peroff (Николай Перов, 1883–1963) and they subsequently met because he saw some of his works hanging on the walls of the studio. As a result of this, Peroff was invited to work as a decorator at the Istanbul theatre. Most likely, though, this life-changing meeting had taken place after the photo studio moved closer to Taksim Square. The photo studio was popular not only among Russian-speaking émigrés, but also among the permanent residents of the Pera district. Countless portrait photographs and pictures for visas originated here. The reasons for this were not only Kanzler’s strong work ethic and accuracy, but also the uniqueness of his photographic works, which looked more like oil paintings. Today, some of his works can be seen in photo archives and even bought at local antique shops.

Collage: Interior of the Jules Kanzler Photo Studio (from Les Russes sur le Bosphore Almanac) and advertisement of the studio in the Presse du Soir Newspaper, 6 August 1921.

03The Mısır Apartments or Mısır Apartmanı (Turkish for “The Egypt Apartments”)/ İstiklal Caddesi 163, Beyoğlu

The Mısır Apartments are located very close to where the Jules Kanzler Photo Studio was once based, but on the right-hand side of Istiklal Street (if you approach from Tünel Square). The building was built in 1870 and is a masterpiece by the Armenian architect Hovsep Aznavuryan. It was called Egyptian because it was built for the Egyptian Khedive Abbas II Helmy, who sometimes stayed here during his visits to Istanbul. Later, the building was divided among the heirs of the Khedive and turned into a dwelling for multiple owners. From then onwards, it began to be used for living spaces and offices. Among the residents were dentists, an antiquarian, a tailor and even the well-known Turkish poet Mehmet Âkif Ersoy. There were also the Russian émigré sculptor Iraida Barry (Ираида Барри, 1899–1980) and her husband Albert Barry, who worked as a dentist. While living in Crimea as a child, Iraida was interested in painting and planned to attend Imperial Academy of Arts of the Russian Empire. After the events of the Russian revolution of 1917, however, Iraida Barry settled in Istanbul, where she took part in at least one exhibition of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople, studied at Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi (Imperial School of Fine Arts), took an active part in the Galatasaray exhibitions, and presented her works in Paris. Iraida not only lived at the Mısır Apartments, but also used parts of its terrace as her studio. She is now remembered as one of the first female sculptors of the Turkish Republic, and many of her works are held by the İstanbul State Art and Sculpture Museum.

The Mısır Apartments, on the left. Most likely this picture was taken after 1907, during the years when Sébah & Joaillier Photostudio was led by the second generation, as Pascal Sébah and Polycarpe Joaillier themselves had already passed away (Sébah & Joaillier Photographie, Istanbul).

Iraida Barry’s studio at the Mısır Apartments (Cengiz Kahraman Koleksyionu, Istanbul).

04Galatasaray Square/ Galatasaray Meydanı, Beyoğlu

A little further down the street, you can see Galatasaray High School (Galatasaray Lisesi), the oldest high school in Turkey. In the early 1920s, several exhibitions of famous Ottoman artists took place in this building – exhibitions were held every year in July-August until 1951, and they were an important event in the cultural life of Istanbul. Since some of these exhibitions were described in detail in the Russian newspapers published in Istanbul, there is every reason to believe that they were visited by many émigrés from the former Russian Empire. Some of them, especially émigré painters and sculptors who cultivated a rather close friendship with the widely known Turkish painters Ibrahim Çallı and Namık Ismail, even participated.

Galatasaray square, 1927. By Selahattin Giz (FKA_005097, © Suna ve İnan Kıraç Vakfı Fotoğraf Koleksiyonu, Istanbul).

Part of Istiklal street close to the Galatasaray square, 1919 (SALT Araştırma, Fotoğraf ve Kartpostal Arşivi, Istanbul).

In the evenings, from 7 to 10 pm, the Russian painters were allowed to work in the studio (presumably Beyoğlu, Hüseyinağa, Tarlabaşı Blv. 79) not far from the Galatasaray High School. According to the announcements in local Russian newspapers of the time, the meetings were to take place at “Küçük Yazıcı 4”. Judging by the Goad maps, this street was located on the site of today’s Tarlabaşı Bulvarı. Most likely, the street was removed due to the widening of Tarlabaşı Street. Despite the fact that this street no longer exists, the building in which the painters held their meetings has survived (although it is possible that in the 1920s it looked differently). Today, the only thing we still know for certain is that the studio’s visitors were mostly members of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople and that the artists created mainly portraits and nudes there. To be able to work in the studio, members of the Union paid 50 kuruş per month, and non-members 10 kuruş for each visit. We also know that the studio served as the base for artists wishing to emigrate to the United States, as registrations were carried out there during November and December of 1922. Despite the fact that there is a lack of information on how these artist meetings exactly looked like, it can be assumed that they resembled the “drawing Thursdays” at Wladimir Ivanoff’s (Владимир Иванов, 1885–1964): “At first, everyone painted from life (usually models were also invited), after everyone drank tea and hotly discussed burning issues of the day” (Novitskiy, “Pamyati hudojnika V.S. Ivanova”, 1965).

Walking down Istiklal street towards the place where the studio used to be in the 1920s (SALT Araştırma, Fotoğraf ve Kartpostal Arşivi, Istanbul).

Tarlabaşı Bulvarı, 1922 (IAE_0028674/39, © Suna ve İnan Kıraç Vakfı Fotoğraf Koleksiyonu, Istanbul).

05Rose Noire (Black Rose, Chernaya Roza) Café-Cabaret,/ Circle d’Orient (İstiklal Caddesi 56/58), Beyoğlu

A few more steps in the direction of Taksim Square, and you will find yourself in front of the Circle D’Orient, the bel étage of which housed the Rose Noire cafe. A streetlamp was used as a cabaret sign and black roses were painted all around the lamp. In the 1920s, the Grand Rue de Péra sported a live advertisement of the cabaret in the form of a black cardboard giant with a red nose, wearing a top hat (Anonymous, “Echo des Theatres”, 1921, 5). This cabaret is known to many people primarily through the memoirs of Alexander Vertinsky (Александр Вертинский, 1889–1957), who performed Russian romantic songs there and intentionally opened the window wide, knowing very well that crowds of fans had gathered outside (Sığırcı 2018, 107). According to some journalists of the time, everything in this cabaret was à la Vertinsky, including the program and waitresses who were dressed in modest black clothes with hairpins on their heads and gold roses embroidered on them. That’s how Vertinsky himself later recalled this place in his memoirs: “I sang in the Chernaya Roza. Of course, not my songs that foreigners did not understand, but mainly gypsy melodies […]. Visitors liked them. Almost every evening, a table was ordered by telephone for the High Commissioner of all occupying forces, Admiral Bristol. He used to come with his wife and with all his retinue, drink champagne […]. He spent a lot of money, and my boss was delighted” (Vertinsky 1991, 133).

Advertisement of the cafe from the Presse du Soir Newspaper, 21 August 1922.

People in front of the Circle d’Orient (Liberation Day of Istanbul). On closer inspection of the picture, one can easily see the streetlamp with black roses painted around (IAE_0028773/093, © Suna ve İnan Kıraç Vakfı Fotoğraf Koleksiyonu, Istanbul).

Circle D’Orient or Grand Pera by Kayıhan Türköz, around the 1980s (SALT Araştırma, Kayıhan Türköz Arşivi, Istanbul).

Circle D’Orient or Grand Pera by Kayıhan Türköz, in the 1980s (SALT Araştırma, Kayıhan Türköz Arşivi, Istanbul).

However, this café was famous not only because of Vertinsky. In 1925, a young Russian painter, Viktor Prokopovich-Czartoryski (Виктор Прокопович-Чарторыйский) or, as he called himself, V.P.-Tch. (В.П.-Ч.), hosted an event there long remembered by its visitors (Aygün, “Boğaz’ın Rusları: 1920’li Yıllarda Beyoğlu’ndaki Rus Göçmen Sanatçılar”, 2021, 14). He created an oriental performance that took the form of several living pictures against the backdrop of stylish ‘Blanc et noir’ decorations. It is interesting that some of these living pictures were accompanied by choreographic “illustrations”; all the costumes for the dancers were also painted by V.P.-Tch. Here is what is said about this event in the Russian press of Istanbul: “Talented ballerina E. Vorobyova staged the ancient Persian ballet in the second ‘Blanc et noir’ living picture and also performed in a special living picture named Salome with the dance of Salome. The decorations of living pictures attracted attention with the style and richness of their ornaments (door, carpets, etc.)” (Anonymous, “Blanc et Noir”, 1925, 10).

06The Russian Lighthouse (Mayak)/ Sadri Alışık 40, Beyoğlu

Almost opposite of the Rose Noire, down Bursa Street (now Sadri Alışık), you could find the Russian Lighthouse (Mayak). This place deserves special attention because it hosted a YMCA centre, where refugees from the Russian Empire were served food in the dining room, were gifted clothes, and where they could arrange visits to the dispensary and employment bureau. Interestingly, at the same time the centre pursued cultural and educational goals which meant that refugees could read books in the library, attend foreign language courses or sports clubs, or take part in poetry evenings and concerts. According to one of the Russian newspapers, this center “brightened up the hard life of a refugee and gave this refugee the opportunity to take a break from the difficult worries of the day” (Anonymous, “Russkiy Mayak v Stambule”, 1922, 3). However, not everyone agreed with this opinion. Some Russian journalists and writers openly hinted that it was not refugees in need who benefited from Mayak, but rather well-fed, careless and hypocritical Russian émigrés from the “elite” who set high prices for everything including food and coteries (Ex-Mason, “Russkiy Mayak”, 1921, 23). Moreover, some Russian intellectuals accused Mayak of being a gathering place for anti-Semitic feelings and masonic inclinations (Kudryavtsev 2016, 85).

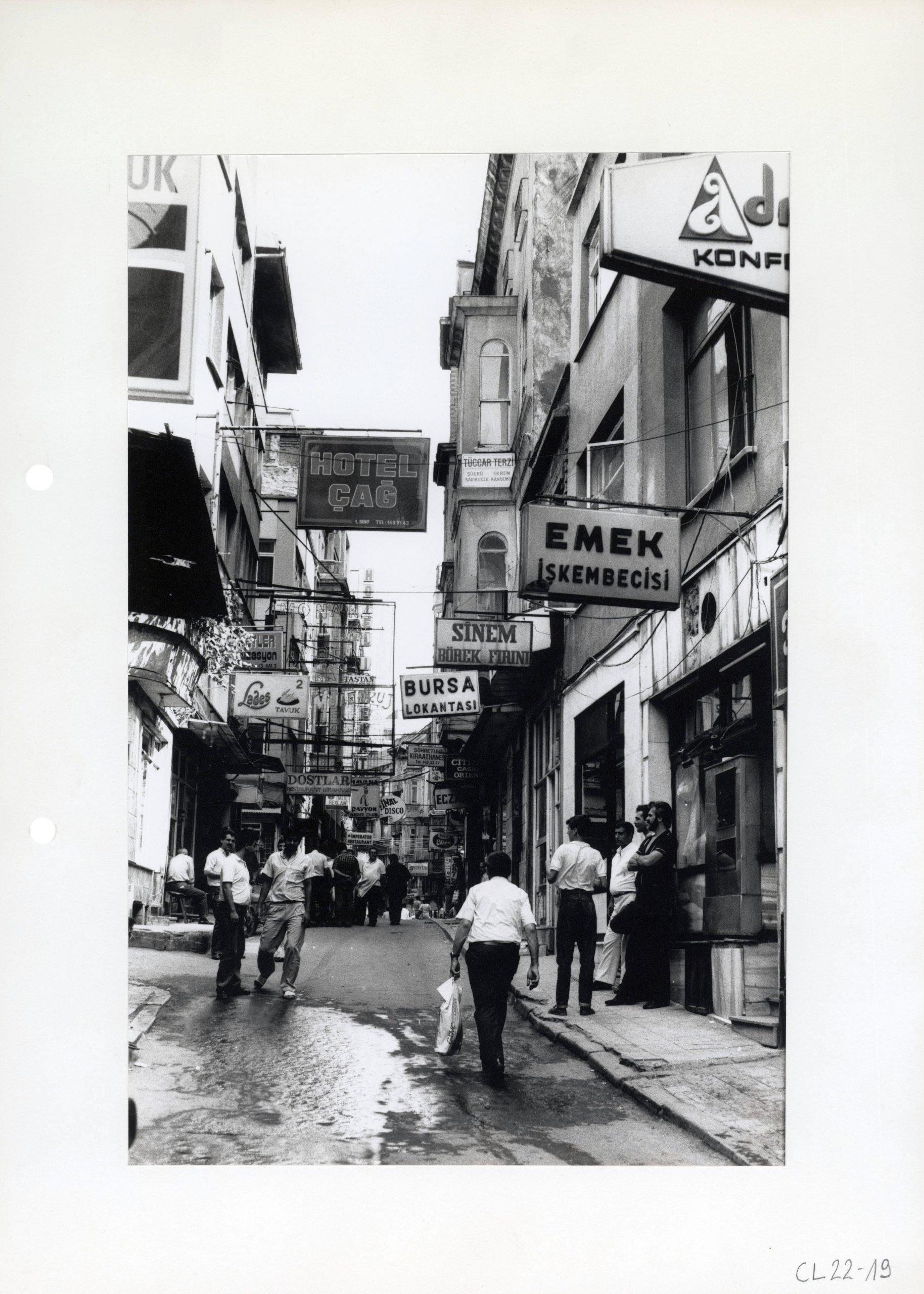

Beyoğlu, Sadri Alışık Street by Marc Eginard, 1987 (SALT Araştırma, IFEA Arşivi, Istanbul).

Nevertheless, for Russian émigré painters Mayak became perhaps the most important place in Beyoğlu, because it was here that a one-day exhibition of paintings was held in October 1921. It was hugely successful and initiated the formation of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople. Here is what the Russian press wrote about this event: “Chances are after this exhibition they (painters) will be remembered and at least the most talented of them will be given an opportunity to work seriously, not to get wet in the rain on the sidewalks, trying to gain some money by selling postcards or caricatures. The Russian Lighthouse kindly agreed to give space for the arrangement of periodic exhibitions” (Anonymous, “Russkiye Hudojniki v Konstantinopole”, 1921, 27). Subsequently, (presumably) nine exhibitions with works by Russian artists took place in this building. Now, it is an ordinary residential building, and I must admit that it is difficult to imagine how it may have looked like at the time. Judging by the photographs in the almanac Les Russes sur le Bosphore, Mayak had a garden.

Sadri Alışık Street, formerly known as Bursa Street, and Ahududu Street (Photo: Ekaterina Aygün, 2020).

Sadri Alışık Street 40, Bursa Palas Apartmanı (Photo: Ekaterina Aygün, 2020).

07Taksim Military Barracks/ Gezi Parkı Gümüşsuyu, Beyoğlu

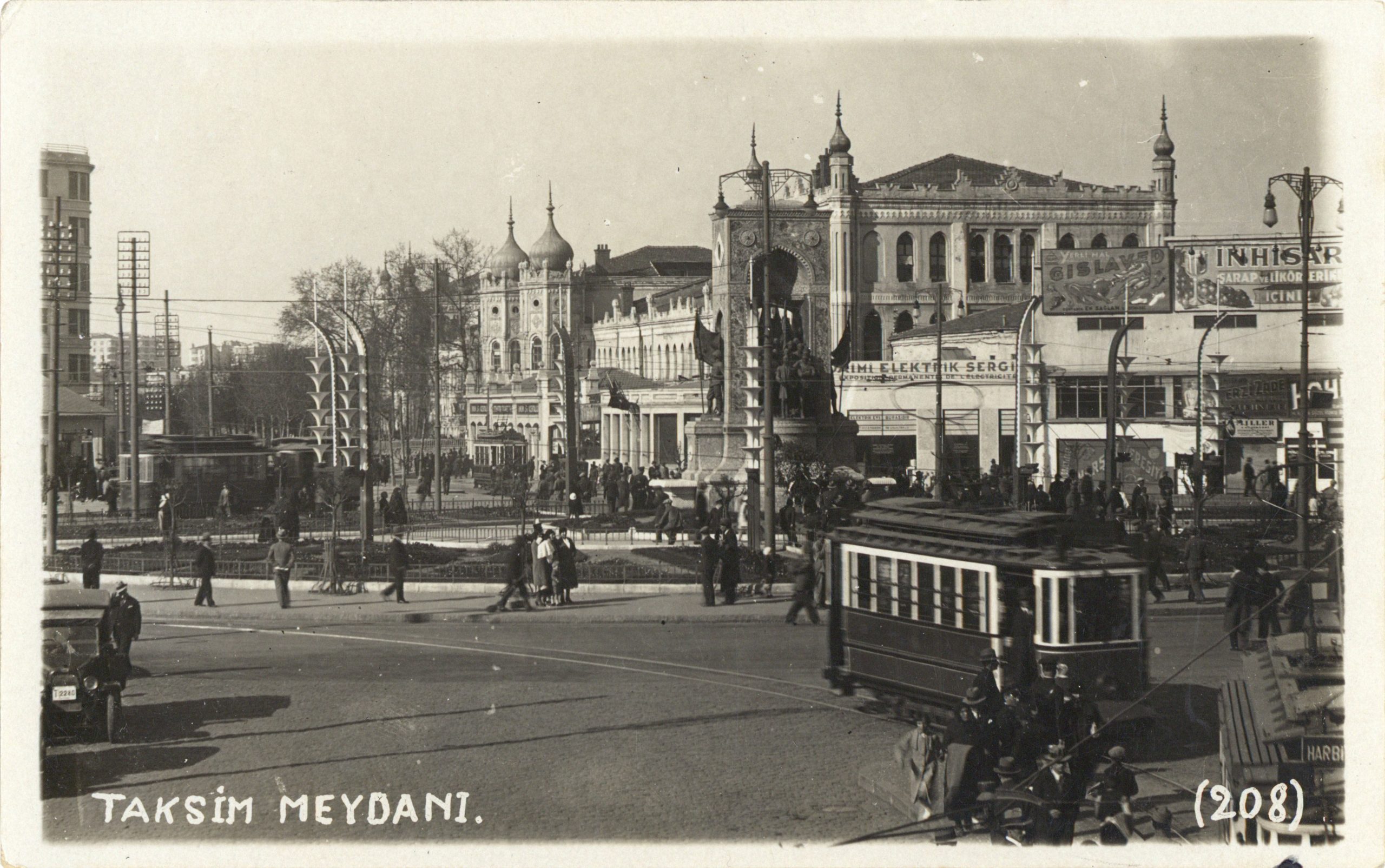

Not all exhibitions held by the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople took place in the Russian Lighthouse (Mayak). Two major exhibitions, for instance, were organized at Taksim Military Barracks. During the occupation of Istanbul, it was more commonly known by the name MacMahon, and that is also how Russian émigrés called this place. It was once located on the grounds of today’s Gezi Park and, in parts, Taksim Square. This is how A. Slobodskoy (1925) described this large military complex with a mosque, cistern, stables and other premises in his memoirs: “Opposite Taksim Square, across the road, there are old, with broken glass and dilapidated Turkish barracks. For a time, they were occupied by French troops and technical teams […]. A number of refugee enterprises also settled in the McMahon barracks: a shelter, a Russian-American garage, driver courses, a veterinary infirmary, running and horse racing with their own stable of racehorses.”

Taksim Military Barracks seen from above, between 1923 and 1940 (SALT Araştırma, Ali Saim Ülgen Arşivi, Istanbul).

Taksim Military Barracks seen from above, between 1923 and 1940 (SALT Araştırma, Ali Saim Ülgen Arşivi, Istanbul).

Taksim Square and Military Barracks, in the 1930s (SALT Araştırma, Fotoğraf ve Kartpostal Arşivi, Istanbul).

One of the exhibitions took place on June 18, 1922, with the assistance of the third secretary of the American Embassy in Istanbul Foster Waterman Stearns. About 500 works by approximately 60 members of the Union were presented at the exhibition. Among other things, this exhibition was notable for the fact that, along with Russian artists and sculptors, members of the Artel of Russian Craftsmen, which had opened on Misk (now Mis) Street in November 1921, also were involved. While in Istanbul, the Artel adhered to the precepts of the Stroganov School for Technical Drawing and fashioned predominantly wood objects (frames, chests, caskets); at the exhibition, they presented 110 items ranging from famous carved woodpeckers to busts made of wood. Another exhibition, organized by Dimitri Ismailovitch (Дмитрий Измайлович, 1890–1976), was held on December 10, 1922. The newspapers of that time wrote that the space was kindly provided by the director of the Société Immobilière, Max Pompée, while the decorative part of the exhibition was entrusted to Nikolai Kalmykoff (Николай Калмыков, Turkish name – Naci Kalmukoğlu, 1896–1951), with a much larger number of exhibits than in the summer. According to the Farewell Almanac, this exhibition was highly acclaimed by the general public as a collection of the finest works of art ever seen in the city. Interestingly enough, after the exhibition the Union’s studio relocated to the barracks for a while. After the formation of the Turkish Republic, the building was turned into a stadium for football matches and other sports competitions. In 1940, the park next to the barracks was expanded, and the buildings thus demolished.

Taksim Square, in the 1930s (SALT Araştırma, Fotoğraf ve Kartpostal Arşivi, Istanbul).

Taksim Square (Photo: Ekaterina Aygün, 2020).

08Hamalbaşı Street/ Beyoğlu

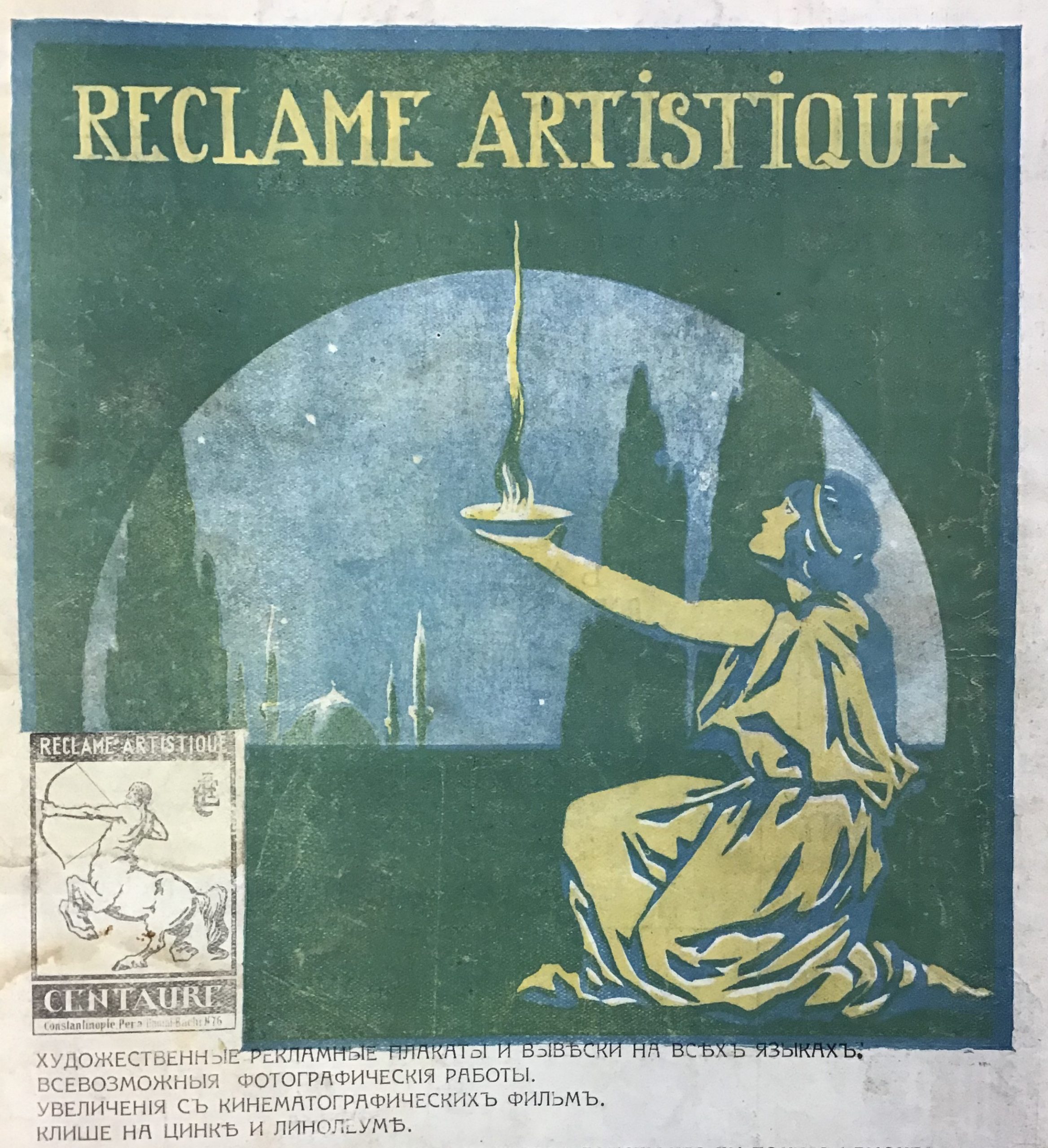

If we move away from Taksim towards Tünel Square, we will reach Hamalbaşı Street. This street, located between Meşrutiyet Street (which at that time housed magnificent hotels of the late 19th and early 20th centuries) and Tarlabaşı Street, is usually associated with old postcards depicting the main attraction of the street, the British Embassy, as well as many street dogs loitering about. In the early 1920s, the Reclam Artistique Studio was situated at number 76. This was a space for Russian émigré painters and photographers, who lived in Istanbul with no substantial means of financial support, to create and produce large numbers of artistic posters, signs in all languages, photographic works, blow-ups from cinematographic films or zinc/linoleum block prints. They worked in this studio in order to earn some money for food and possibly a roof over their heads.

Advertisement of the Reclam Artistique Studio from the Nashi Dni Almanac no. 5, 1921.

Hamalbaşı Street, postcard, in the 1900s (Eski İstanbul Fotoğrafları Arşivi, eskiistanbul.net).

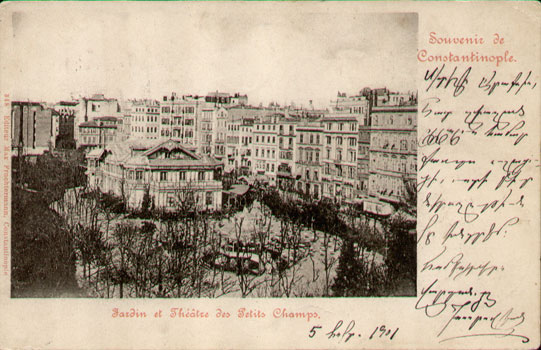

09Tepebaşı Dram Tiyatrosu / Theatre des Petits Champs/ Meşrutiyet Caddesi 50, Beyoğlu

Let’s walk back to Meşrutiyet Street and move toward the Theatre des Petits Champs at Tepebaşı, which means “hilltop” in Turkish. This is due to the previously mentioned Tunnel, during the construction of which a lot of ground was dug up and eventually emptied out here. Over time, the hills transformed into the so-called “Hilltop Gardens”, the main attraction of which, in addition to circuses and other entertainment establishments, was the theatre which opened its doors to visitors until it was destroyed by two big fires in 1970 and 1971. Unfortunately, the site of the theatre is now occupied by a parking lot which is why we can no longer see the glamorous place which put on ballets and other splendid Russian performances.

Tepebaşı in the 1900s (SALT Araştırma, IFEA Arşivi, Istanbul).

We know that Russian-speaking émigré artists – such as Pavel Tchelitchew (Павел Челищев, 1898–1957), Leonid Brailowsky (Леонид Браиловский, 1867–1937), Vladimir Bobritsky (Владимир Бобрицкий, 1898–1986), Nikolai Kalmykoff, Nikolai Vasilieff (Николай Васильев, 1887–1970) and Nikolai Peroff – worked for the theatre to create decorations and costumes. The decorator of the Moscow Bolshoi Theater, Brailowsky, for example created the scenery for Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich while staying in Istanbul. Scheherazade, a tale from One Thousand and One Nights and based on the music of Rimsky-Korsakov, was presented by Zimin (Зимин), ballet master of the Moscow theatres, with new decorations and costumes made according to the sketches of the painter Nikolai Vasilieff (Aygün, “Boğaz’ın Rusları: 1920’li Yıllarda Beyoğlu’ndaki Rus Göçmen Sanatçılar”, 2021, 11). Here is what the press wrote about this performance: “It was a vivid performance, pleasing to the eye and caressing the ear […]. Vasilieff’s excellent scenery, evoking Bakst’s best works in terms of richness and splendour of colours, rich costumes and a general charm of the ambience, rich and colourful, created an atmosphere of captivating oriental fairy-tale that gripped the attention of the audience […]. In a word, it was an excellent ballet performance that had never been seen in Constantinople. The financial success of the evening was in line with its artistic one. The theatre was full” (Anonymous, “Sheherezada”, 1921, 2).

Tepebaşı Theatre, postcard (Selçuk Yüksel Koleksiyonu, Istanbul).

Tepebaşı Theatre, interior (Selçuk Yüksel Koleksiyonu, Istanbul).

Vladimir Bobritsky also worked at the Theatre des Petits Champs – it was here that he designed the scenery for the ballet Pan. Interestingly, his decorations were a combination of the antique and the futuristic, which led some critics to accuse the painter of “imbalance in the direction of excessive modernism” (Anonymous, “Pan Balet”, 1922, 3). In their opinion, this combination violated the unity of the overall impression. However, apparently, the artist took into account all feedback, because his scenery for The Magic Flute, again according to critics, was “less pretentious”, and the scenery for the new version of Scheherazade was recognized as very “spectacular” (Anonymous, “Volshebnaya fleyta Balet”, 1922, 3). Bobritsky successfully worked in this theater for a long time. After his departure to New York in January 1923, Kalmykoff and much later Peroff, who was invited to the theatre by Muhsin Ertuğrul, took his place.

Rue des Petits-Champs – Constantinople, postcard (SALT Araştırma, Fotoğraf ve Kartpostal Arşivi, Istanbul).

Tepebaşı area, walking down the street towards Pera Palace. By Selahattin Giz (FKA_001032, © Suna ve İnan Kıraç Vakfı Fotoğraf Koleksiyonu, Istanbul).

10Pera Palace/ Meşrutiyet Caddesi 52, Beyoğlu

From where the theatre was situated, one can easily reach the most famous hotel of Pera, Pera Palace. Construction of the hotel began at the end of the 19th century; the building was designed by the architect Alexandre Vallaury (born Alexander Vallauri) and was built for tourists who came to Istanbul on the long-distance passenger train, the Orient Express. The hotel’s restaurant served excellent food and wines, musical evenings were very popular, balls were held, Christmas and New Year were celebrated. Among the hotel’s guests of honour was Agatha Christie, who, according to legend, found inspiration to write her detective novel Murder on the Orient Express while staying at Pera Palace. The building has undergone restoration, but remains a fine example of late-nineteenth-century Istanbul architecture. It was here that the Russian bazaar was held in 1921, where, in addition to all other works, the icons of the artist Natalia Yashvil (Наталья Яшвиль, 1861–1939) or Jašvili (who later left Istanbul for Prague) were presented. All these icons were sold to one of the American collectors before the Bazaar even opened. The hotel also saw two remarkable exhibitions in 1921 and 1922 by the Russian émigré painter Nikolai Becker (Николай Беккер, 1877–1962), who created portraits of prominent people of that time (including Foster Waterman Stearns and Mark Lambert Bristol). In addition, the aforementioned Vertinsky lived here for some time: “Boris Putyata and I settled no more and no less than in the most fashionable hotel of Constantinople, the Pera Palace. We ironed our Russian ‘suits’ – actor’s famous ‘wardrobe’ –, looking at which entrepreneurs sternly appraised young actors, and […] went out into the street. On the Grand Rue de Péra, many of our compatriots who had arrived before us were already walking back and forth. Putyata even stuck a carnation in his buttonhole. We walked just like at home – somewhere in Kharkiv, on Sumskaya” (Vertinsky 1991, 124). There are a myriad of stories to be told about this legendary hotel, and it was and still is without any doubt the gem of the Pera district.

Meşrutiyet Street and Pera Palace Hotel, 1941 (SALT Araştırma, Fotoğraf ve Kartpostal Arşivi, Istanbul).

View from the Pera Palace Hotel's window. By Sebah & Joaillier (FKA_000613, © Suna ve İnan Kıraç Vakfı Fotoğraf Koleksiyonu, Istanbul).

TUTTA, one of the first Turkish travel agencies, founded in the 1920s (Turkish Travelling & Tourist Agency), opposite of the Pera Palace, Asmalımescit, Beyoğlu (SALT Araştırma, Fotoğraf ve Kartpostal Arşivi, Istanbul).

Acknowledgements

My deepest thanks go to İstanbul Research İnstitute, Slavonic Library (Slovanská knihovna) in Prague, SALT Araştırma in Istanbul, Neslihan Yalav (Istanbul Çelik Gülersoy Library), Evelina Davydova, Cengiz Kahraman and Selçuk Yüksel.

Bibliography (selection)

Akıncı, Turan. Beyoğlu. Yapılar, mekanlar, insanlar (1831–1923). Remzi Kitabevi, 2018.

Akpamuk, Günce. “İraida Barry’nin İstanbul günleri.” Atlas Tarih, January–February, 2020, pp. 116–121.

Anonymous. “Iraida Barry (1899–980) – Russkiy scul’ptor Stambula.” domrz.ru, https://www.domrz.ru/exhibition/iraida_barri_1899_1980_russkiy_skulptor_stambula_/. Accessed 20 August 2020.

Anonymous. “Russkiy Montparnass.” domrz.ru, https://www.domrz.ru/exhibition/russkiy_monparnas/. Accessed 5 July 2020.

Anonymous. “Russkiy Mayak.” Russkaya Volna, Novogodniy vypusk [New Year edition], n.d., p. 21.

Anonymous. “Russkiy Mayak.” Russkaya Volna, no. 4, 1921, p. 12.

Anonymous. “Echo des Theatres.” Jizn’ i Iskusstvo, 6 February 1921, p. 5.

Anonymous. “Bazar kn. M.V. Baryatinskoy.” Zarnitsy, 20 March 1921, p. 23.

Anonymous. “Tret’ya vystavka kartin turetskih hudojnikov.” Presse du Soir, 2 September 1921, p. 5.

Anonymous. “Odnodnevnaya vystavka kartin.” Presse du Soir, 10 October 1921, p. 4.

Anonymous. “Russkiye Hudojniki v Konstantinopole.” Zarnitsy, 23 October 1921, p. 27.

Anonymous. “Sheherezada.” Presse du Soir, 31 December 1921, p. 2.

Anonymous. “Vystavka hudojnika N.N. Beckera.” Presse du Soir, 20 May 1922, p. 3.

Anonymous. “Russkiy Mayak v Stambule.” Slovo, 18 June 1922, p. 3.

Anonymous. “Vystavka Soyuza Russkih Hudojnikov.” Presse du Soir, 19 June 1922, n.p.

Anonymous. “Volshebnaya fleyta Balet.” Presse du Soir, 10 August 1922, p. 3.

Anonymous. “Vystavka Russkih Hudojnikov.” Presse du Soir, 8 December 1922, p. 3.

Anonymous. “Blanc et Noir.” Zarubejniy Klich, 1925, p. 10.

Aygun, Ekaterina. “İkinci Ev Bulma Öyküsü.” Sanat Dünyamız, no. 177, 2020, pp. 46–51.

Aygün, Ekaterina. “Boğaz’ın Rusları: 1920’li Yıllarda Beyoğlu’ndaki Rus Göçmen Sanatçılar.” Toplumsal Tarih, no. 330, 2021, pp. 9–15.

Bournakine, Anatoliy, and Dominic Valery, editors. Al’manah Na Proschaniye. The Farewell Almanac. L’Almanach Nos Adieux (1920–1923). Imp. L. Babok & fils, 1923.

Bournakine, Anatoliy, editor. Russkiye na Bosfore. Les Russes sur le Bosphore. Imp. L. Babok & fils, 1927.

Çelik, Yüksel. “Mit ve Gerçek Arasında: Taksim Topçu Kışlası (Beyoğlu Kışla-i Hümayunu).” Osmanlı İstanbulu. III. Uluslararası Osmanlı İstanbulu Sempozyumu, edited by Feridun M. Emecen, Istanbul 29 Mayis Üniversitesi, 2015, pp. 443–476.

Chebyshev, Nikolay. Blizkaya Dal’: Vospominaniya. Imp. de Navarre, 1933.

Dirican, Gül. “Uzak ve Yalnız İraida.” Gazete Pazar, 16 February 1997, p. 19.

Eminoğlu, Münevver, editor. 1870 Beyoğlu 2000. Bir Beyoğlu Fotoromanı. Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık, 2004.

Eracun, Selçuk, et al. Bir Pera Masalı. Dünden Bugüne Resimli Pera Tarihi. Destek Yayınları, 2020.

Evren, Burçak. “Jules Kanzler.” Tombak, no. 27, 1999, pp. 4–6.

Ex-Mason. “Russkiy Mayak.” Zarubejniy Klich, 1921 (Sofia), p. 23.

Freely, Brendan, and John Freely. Galata, Pera, Beyoğlu: Bir Biyografi. Translated by Yelda Türedi, YKY, 2014.

Genim, M. Sinan, and Yücel Dağlı, editors. Geçmişten Günümüze Beyoğlu I–II. Türkiye Anıt Çevre Turizm Değerlerini Koruma Vakfı, 2004.

Giray, Kıymet. Çallı ve Atölyesi. Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 1997.

İnal, Onur. Pera’dan Beyoğlu’na. E Yayınları, 2012.

Kasimova, İrina. Po mestam prebyvaniya beloy ėmigratsii v Stambulʹskom rayone Pera. Consulate General of the Russian Federation in İstanbul et al., 2011.

King, Charles. Pera Palas’ta Geceyarısı. Modern Istanbul’un Doğuşu. Translated by Ayşen Anadol, ALFA Tarih, 2019.

Kudryavtsev, Sergey. Zaumnik v Tsargrade. Itogi i dni puteshestviya I.M. Zdanevicha v Konstantinopol’ v 1920–1921 godah. Grundrisse, 2016.

Novitskiy, G. “Pamyati hudojnika V.S. Ivanova.” Novoye Russkoye Slovo, 23 December 1965, n.p.

Olcay, Türkan, editor. Russkaya Belaya Emigratsiya v Turtsii vek spustya 1919–2019. DRZ, 2019.

Section No:43 of Charles E. Goad Insurance map of Pera district dated 1905 (SALT Research, Istanbul, 1905), AEXAS041.

Sığırcı, Marina. Spasibo, Konstantinopol’! Po sledam beloemigrantov v Turtsii. “Yevropeyskiy Dom”, 2018.

Slobodskoy, A. Sredi Emigratsii: Moi Vospominaniya. Izdatel’stvo “Proletariy”, 1925.

Tekeli, İlhan, et al. Dünden Bugüne Istanbul Ansiklopedisi (Vol. 5, 6). Kültür Bakanlığı ve Tarih Vakfı, 1994.

Vertinsky, Aleksandr. Dorogoy dlinnoyu… İzdatel’stvo “Pravda”, 1991.

Yüksel, Selçuk. “Yüzyıllık Efsane ‘Tepebaşı Dram Tiyatrosu’.” tiyatromuzesi.org, https://tiyatromuzesi.org/drupal/tepebasi_dram_tiyatrosu.html. Accessed 10 June 2020.