Buenos Aires

Artistic Exile and the Cityscape of Buenos Aires (1920s-1950s)

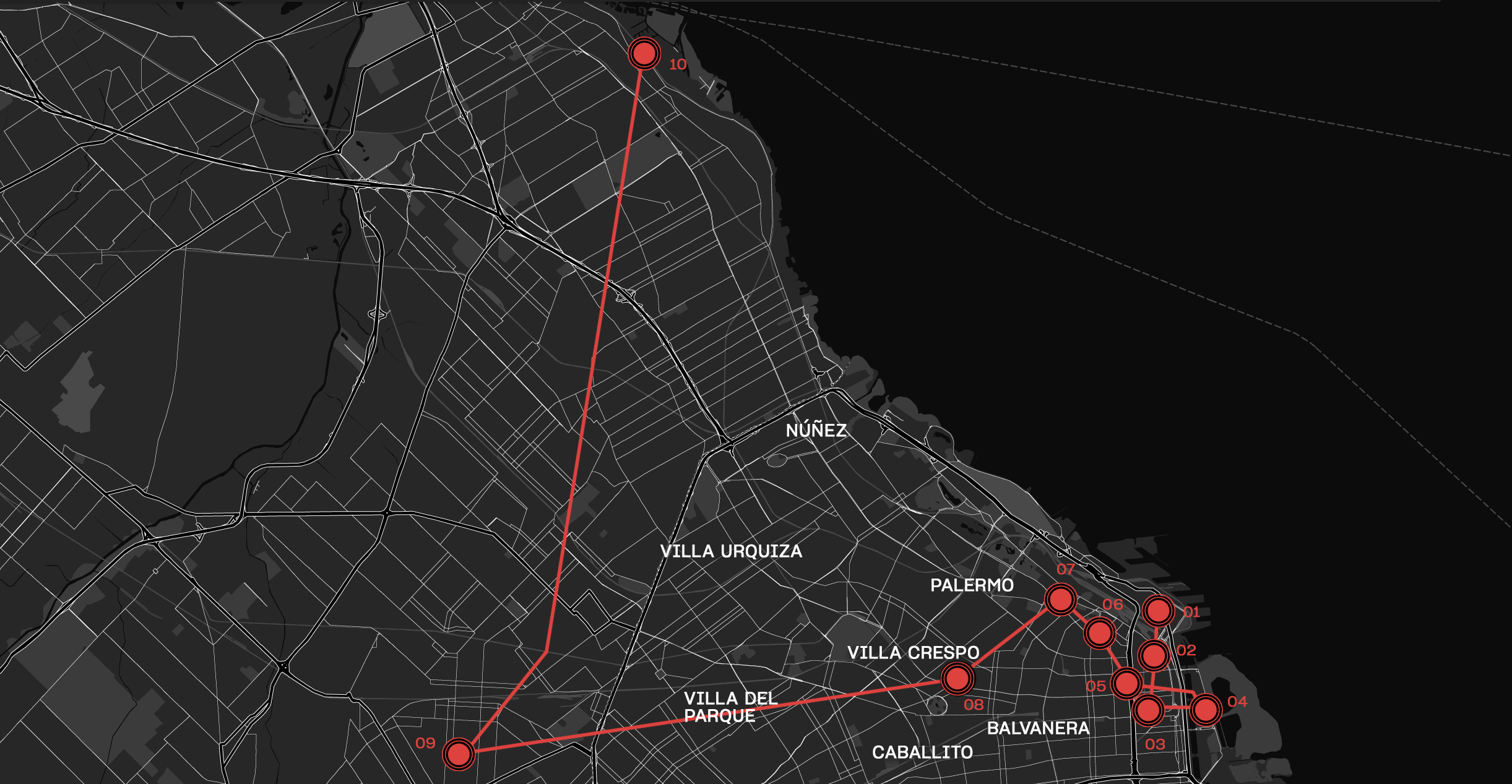

Buenos Aires is a metropole that opens out to the Río de la Plata river estuary, from its north-western points to its south-eastern neighbourhoods. Since the 1880s, countless migrants have arrived by ship from European ports on the Río de la Plata, looking for better economic and socio-political conditions. In just thirty years, migrants tripled the population count of Buenos Aires. This demography led to the establishment of institutions and meeting spaces which were founded by immigrants (including exiles who were forced to migrate) in order to encourage socio-cultural encounters. Associations, leisure centres, schools, hospitals, foreign-language newspapers and clubs were set up for and by many exiled communities, bringing together newcomers with shared national or linguistic roots to make them feel at home, and to foster their integration in Buenos Aires. Let’s start our walk at the Hotel de Inmigrantes, the first point of contact with Argentina for most newcomers.

miles 672

min. 10

sights foot, bus & urban train

01Hotel de Inmigrantes/ Avenida Antártida Argentina 1355, Retiro

Facing the river, on Avenida Antártida Argentina 1355, stands the stunning building that houses the Hotel de Inmigrantes (Hotel of Immigrants), just a few meters from the docks where ships carrying passengers to Buenos Aires from European ports regularly docked before air transport became popular in the 1960s.

The docks first saw the addition of a landing platform to make it easier for passengers to embark; this was followed by a job search agency, a hospital, and finally a hotel. In close proximity to the landing stage, and located at the intersection of the Costanera Norte and Costanera Sur promenades, the Hotel de Inmigrantes was inaugurated in 1911 – it was designed by the Hungarian architect Juan Kronfuss and its construction was carried out by the German company Wayss & Freytag. The hotel was planned as a four-storey reinforced concrete building. Each floor has a central corridor which leads into wide, expansive spaces. The architecture of the building responded to the needs and slogans of the hygienist movement, which, at the beginning of the 20th century, proposed to combat the spread of diseases by designing bright, oxygenated and open spaces that were easy to clean.

Built to provide protection, shelter, and other facilities to immigrants who needed them, the Hotel of Immigrants operated for more than forty years. Indeed, the last of the one million immigrants accommodated at the hotel was registered in 1953. In the hotel, newcomers could find food, a bed, and medical assistance to cure diseases caught on the ships. They were assisted in obtaining residency permissions, taught how to use agricultural machines to work in rural areas or to join factories, and they eventually also got assistance in finding work. These processes have to be understood in the context of the Argentinian “open door” immigration policy which, despite some attempts at regulation and control, remained in place without major changes until 1930.

Hotel of Immigrants. View of Buenos Aires with the Hotel of Immigrants at the back on the shore, n.d. (© Archivo Nacional de la Nación, Buenos Aires).

Hotel of Immigrants, corridor (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2017).

Hotel of Immigrants, dining room, n.d. (© Archivo Nacional de la Nación, Buenos Aires).

After it was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1990, renovation works were carried out by the Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero in 2011. Since then, the university shares the building with the National Directorate of Migration, which runs offices and archives there. The Hotel of Immigrants also hosts the Museum of Immigration and the Center for Contemporary Art.

The hotel is a symbolic starting point for the immigrant and exile community in Buenos Aires. As it received and welcomed arriving ships and their passengers, it embodies the union of Argentina and Europe. Many migrants passed through its facilities, many others did not, but for all of them the hotel remains a building full of memory: an emblematic place in the history of immigration in Argentina in the first half of the 20th century. A kilometre away begins Calle Florida (Florida Street), which was already then one of the busiest streets in Buenos Aires. Department stores of international brands, art galleries and publishing houses flourished on both sides of the street.

Exhibition room at the Museo de la Inmigración (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2017).

02Calle Florida 1000/ San Nicolás/Retiro

The old district of Buenos Aires, its heart located on Calle Florida (Florida Street), functioned as a contact zone where a rich artistic life developed: it featured galleries, shops for artists’ equipment, photography studios, institutions and different associations. On this street and throughout its surrounding areas, local and migrant artists gathered, exchanged ideas and exhibited their work together. You could also find European migrants among the city’s successful merchants and bar owners, among gallerists and the members of many liberal professions such as writers, artists and architects. The mutual aid networks of European immigrants in Buenos Aires had a significant impact on the art scene. Some migrants set up as art dealers: José Artal, José Pinelo Llull, and Justo Bou Álvaro, Spanish merchants, worked hard to make visible the art produced in Buenos Aires by their compatriots. Many other migrant gallerists settled here — this is what enabled the photographer Grete Stern to have her first solo exhibition at Galería Müller in 1943, for example.

The German born Federico C. Müller exhibited artworks in the basement of a shop of decorative objects he opened on Florida 361 in 1909, before moving up the street to Florida 935, in 1913. A few meters away, the English photographer Alejandro Witcomb had opened an exhibition space in 1897 (Florida 364), before moving to Florida 900 into a large gallery with glass ceilings. Witcomb sought to attract an affluent audience, the upper class of Buenos Aires. The Italian born Frans van Riel’s arrived in Buenos Aires in 1910. Three years later, he opened a photography studio on Calle Viamonte, between Maipú and Florida. In 1924, he moved down to Florida 659 and opened a gallery which hosted the Asociación Amigos del Arte (Friends of Art Association, 1924–1942). Particularly beneficial for migrant artists, the association provided them with a space for both dialogue and displaying their art. Among many others, the exiled photographer Gisèle Freund took part in one of its shows at Galería Van Riel in 1942.

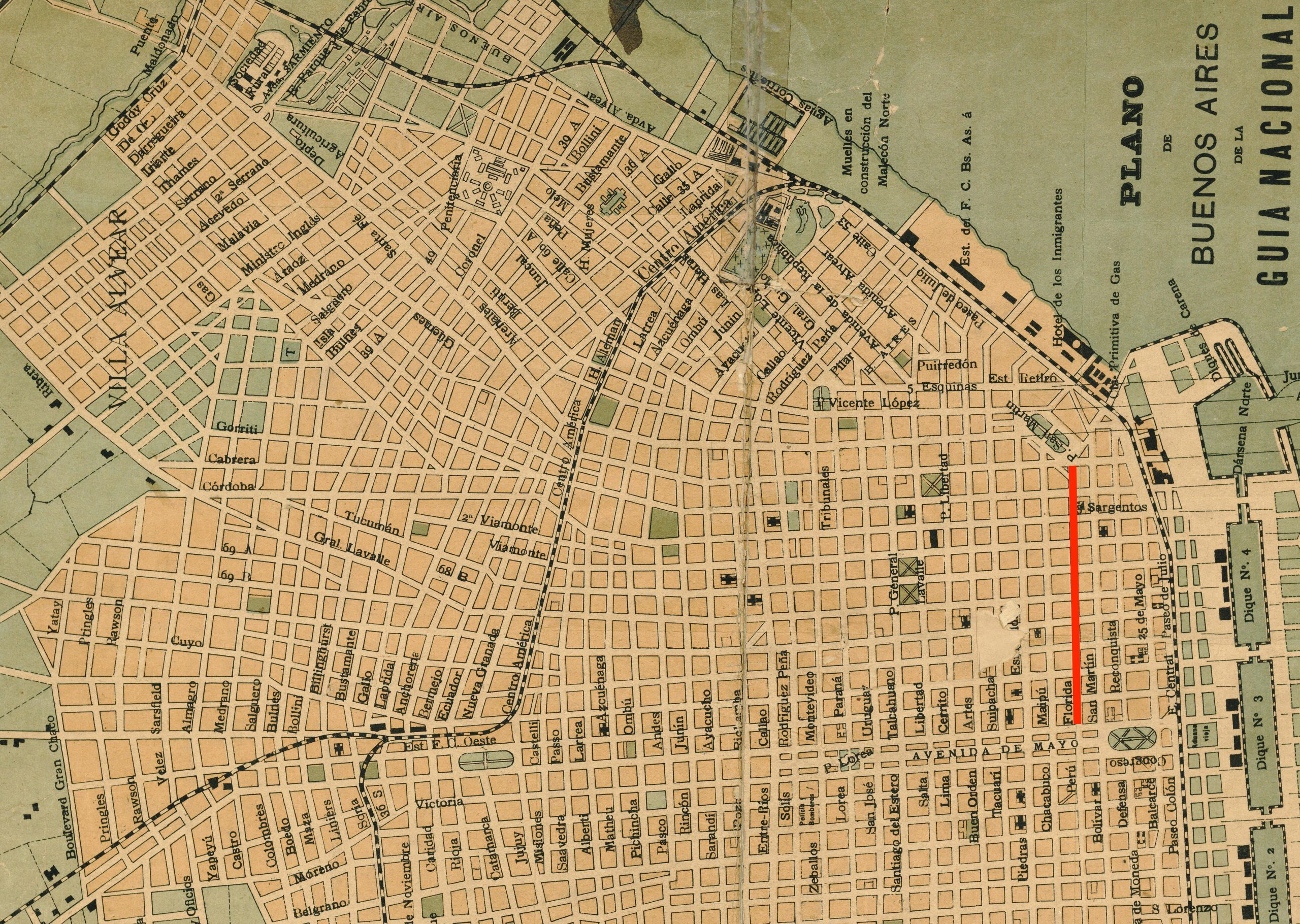

View of Florida street. Map of Buenos Aires (detail), 1895 (© Archivo General de la Nación, Buenos Aires).

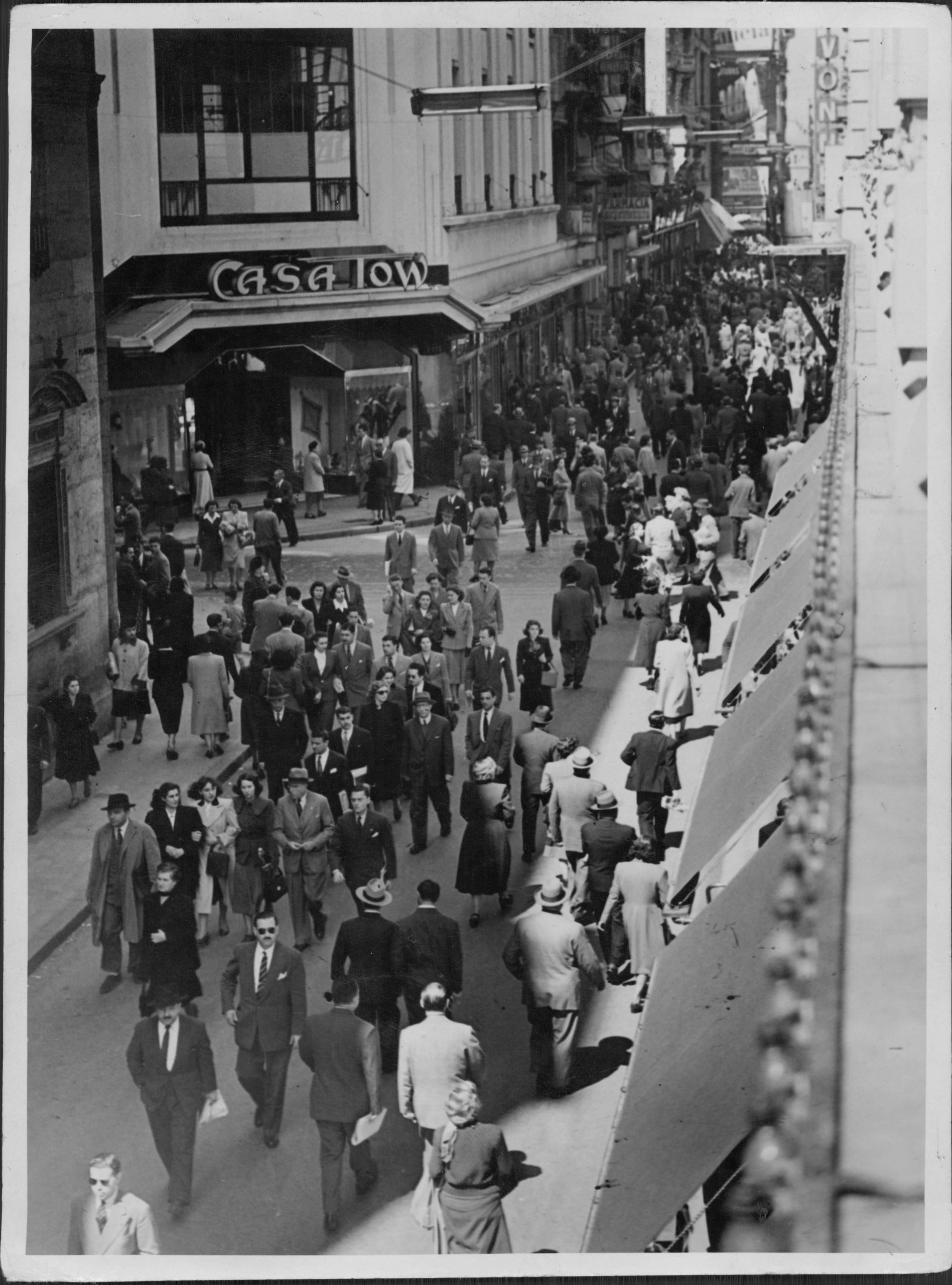

Calle Florida constituted a strategic metropolitan connecting line. Since the birth of Buenos Aires, Florida had acted as the nodal point for the social life of the city. In the days of Independence, Salons were held there, including those of Mariquita Sánchez and Flora Azcuénaga which gathered local and foreign elites. Located about 400 meters from the banks of the Río de la Plata that opens out to the Atlantic Ocean, Florida rises parallel to it, until it merges into Plaza San Martín (former Plaza de Marte) which also faces the river in its northern part. In 1911, Florida became pedestrianized and commercial, linking the central district to Retiro, in the north. Shops, galleries and studios multiplied on either side of the street, which was and still is one of the city’s most central and well-known axes. Clustered on this 1.3 km long pedestrian street, art galleries, shops, clubs and associations could expect a consistently high number of shoppers, visitors, aficionados and flâneurs. This stimulating social and professional environment led the artists of Buenos Aires to practice forms of self-organization by setting up societies and associations, and by opening private spaces where they could gather.

Intersection of Florida and Cangallo, n.d. (© Archivo Nacional de la Nación, Buenos Aires).

Horacio Coppola, Florida Street at 8pm, 1930s (published in Buenos Aires: visión fotográfica por Horacio Coppola, 1937, 107).

At the turn of the 20th century, many other establishments were located here, such as Galería Londres, Salón Chandler y Thomas, Jockey Club, and — at the crossroads with this street — the Galería Philipon and the Salón Eclectique, as well as the most prestigious commercial buildings: Galerías Pacífico (1890), Galería Güemes (1915) and Harrod’s (1914), among many others. Some places still carry traces of the passage of exiled artists on their walls. A series of mural paintings created in 1946 occupy the 450m2 of the central dome of Galerías Pacífico, including one by the Spanish painter Manuel Colmeiro, as well as others by the Argentinian artists Antonio Berni, Juan Carlos Castagnino, Lino Enea Spilimbergo and Demetrio Urruchúa. According to his compatriot, the artist Luis Seoane, Colmeiro evokes his native Galicia in his work.

Galerías Pacífico, outside view (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2019).

Manuel Colmeiro’s mural painting on the walls of Galerías Pacífico (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2019).

From 1917 on, the building constructed by the Belgian architect Julio Dormal at Calle Florida 468 hosted the traditional confectionery Confitería Richmond. This place was a historic meeting point for artists and intellectuals until its closure in 2011. The editors of the art and critical journal Martín Fierro (1924–1927) met in Richmond, thus forever linking the confectionery to the Florida literary group.

Commemorative panel of the confectionery Richmond (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2019).

03Café Tortoni/ Avenida de Mayo 825, Montserrat

The oldest of the still standing cafés in Buenos Aires is El Tortoni, originally founded in 1858 by Touan, a French migrant, and situated today on the ground floor of a neoclassical building built by the Norwegian architect Alejandro Christophersen in 1898 on the new Avenida de Mayo, which had been inaugurated ten years before. The painter Benito Quinquela Martín founded “La Peña”, a group of artists who regularly met in the Café Tortoni. The stained-glass windows of the café were designed by the Catalan painter Antoni Estruch i Bros, who had settled in Buenos Aires in 1910. There, he held the position of director of the School of Fine Arts and had a studio at Calle Piedras 1019, a mere 15-minute walk from the café. Estruch i Bros also worked for Las Violetas, another legendary café located in the Almagro district (Avenida Rivadavia 3899).

Café Tortoni, facade on Avenida de Mayo (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2019).

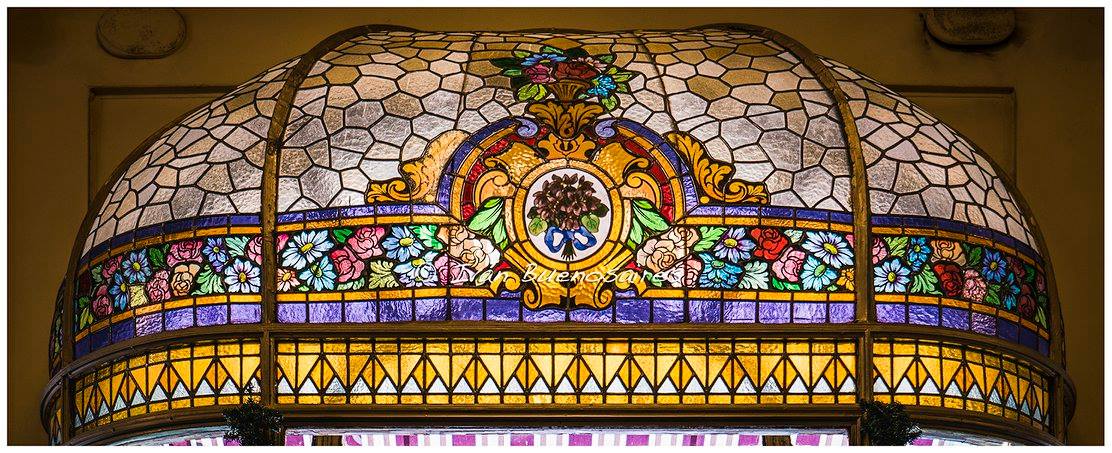

Las Violetas was founded in 1884 on Avenida Rivadavia 3899, at the intersection with Avenida Medrano, in the Almagro district which was then far from the city centre. Two Portuguese immigrants opened this confectionery that took its name from the colour of the flowers sold on the corner it occupied. Las Violetas is today one of the most elegant and traditional bars in the city.

In 1924, some structural works gave a new face to Las Violetas: marble, boiseries and furniture arrived from Paris to luxuriously decorate the wide spaces of the confectionery. Its stained-glass windows were, again, conceived by the Catalan artist Antoni Estruch i Bros, who was also involved in the refurbishment of the Café Tortoni. His colourful work particularly stands out when the sun passes through the windows, contributing to the extraordinariness of Las Violetas. In exile, Estruch i Bros dedicated himself mainly to the design and creation of artistic stained glass, as well as to portrait painting.

Confitería Las Violetas, outside view, on the intersection of Avenida Medrano and Avenida Rivadavia (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2019).

Confitería Las Violetas, main room (Photo: Iván Buenosaires, 2019).

Confitería Las Violetas, stained-glass windows (Photo: Iván Buenosaires, 2019).

Confitería Las Violetas, stained-glass windows (Photo: Iván Buenosaires, 2019).

04Cervecería Munich/ Avenida de los Italianos 851, Puerto Madero

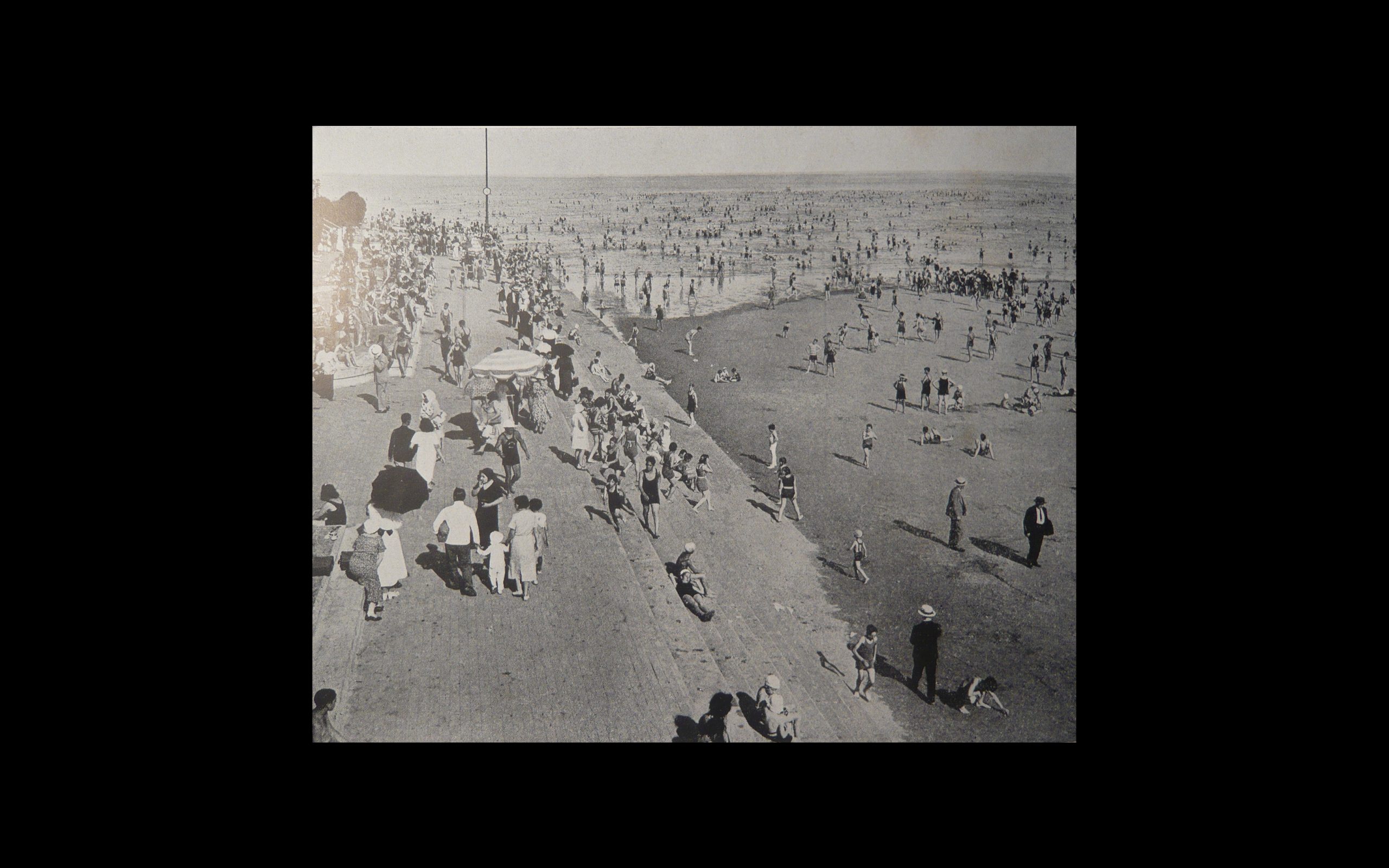

As part of a land reclamation project, the Costanera — the waterfront promenade — opened on the east coast of the city and, by 1918, had become an area for multiple holiday resorts. Here, on Avenida de los Italianos 851 (Puerto Madero), the Catalan entrepreneur Ricardo Banús commissioned the exiled Hungarian architect Andrés Kálnay to build a new social space, the Cervecería Munich (a brewery and beer hall), in 1927. The foundations of the construction demanded special attention as the land on which it was being built was not stable. For it to resemble a Bavarian Biergarten, Kálnay built a building which was largely open to the outside, with a central space and several terraces. It was decorated with designs that referred to the main object of interest: beer. The Hungarian also took care of the inside design, of the furniture and objects: railings, lamps, stained-glass windows (with Bavarian motifs), furniture and crockery. The building follows a rigorous symmetry that contrasts with the eclectic style of its ornaments, a mixture of art-deco, Jugendstil and secession style. Enrique Schwindsackl carved most of the sculptures on the external walls of the building: animals and people dressed in typical Bavarian costumes supported by small corbels. The brewery operated until the 1970s. After it lay abandoned for some time, the building was restored by Kálnay itself. Thus, in 2002, the Museum of Humour opened its doors in what would henceforth be called the former Cervecería Munich’s building.

Horacio Coppola, La Costanera, municipal bath (east), c. 1936 (Buenos Aires 1936…, 1937).

Cervecería Múnich, outside view (Photo: Iván Buenosaires, 2018).

Cervecería Múnich, inside view (Photo: Iván Buenosaires, 2018).

05Obelisco/ Plaza de la República, Avenida Corrientes 1051, San Nicolás

The architect Alberto Prebisch, born in Argentina to a German father, left an important imprint on the city. In addition to private homes, including the house of his brother Raul Prebisch, and the Ocampo building, located at Calle Chile 1368, he built the Obelisk which is undoubtedly the most well-known emblem of the city. Located at the intersection of Avenida Corrientes, Avenida 9 de Julio and Diagonal Norte, right in the middle of Plaza de la República, this tall four-sided monument is representative of Prebisch’s rational, purist and functional aesthetic. The commission from the Argentinean government took place in the context of the festivities for the 400th anniversary of the founding of Buenos Aires. The construction of the obelisk is part of a series of refurbishments carried out in Buenos Aires’ public thoroughfare — including the widening of Avenida Corrientes, the opening of Diagonal Norte, the opening of the Avenida Norte-Sud (today 9 de Julio) and the implementation of two new urban metro lines —, and is located at the geographic centre of all of them.

Grete Stern, Obelisk, Buenos Aires, 1951/52 (Príamo 1995, 80).

Avenida Corrientes went from being a street to a wide avenue mainly for traffic reasons, but also so that the city government could restructure the city centre and its surrounding neighbourhoods. Once reconstructed and widened, however, this axis was immediately appropriated by its passers-by who turned Corrientes into a unique nodal point in the city. To this day, it is a place of passage and destination by day as well as by night. In the downtown area, the bookstores and cafés located on the avenue remain open all night.

Horacio Coppola, Avenida Corrientes, c. 1936 (Buenos Aires 1936…, 1937).

06Photo Studio Annemarie Heinrich/ Avenida Callao 1475, Recoleta

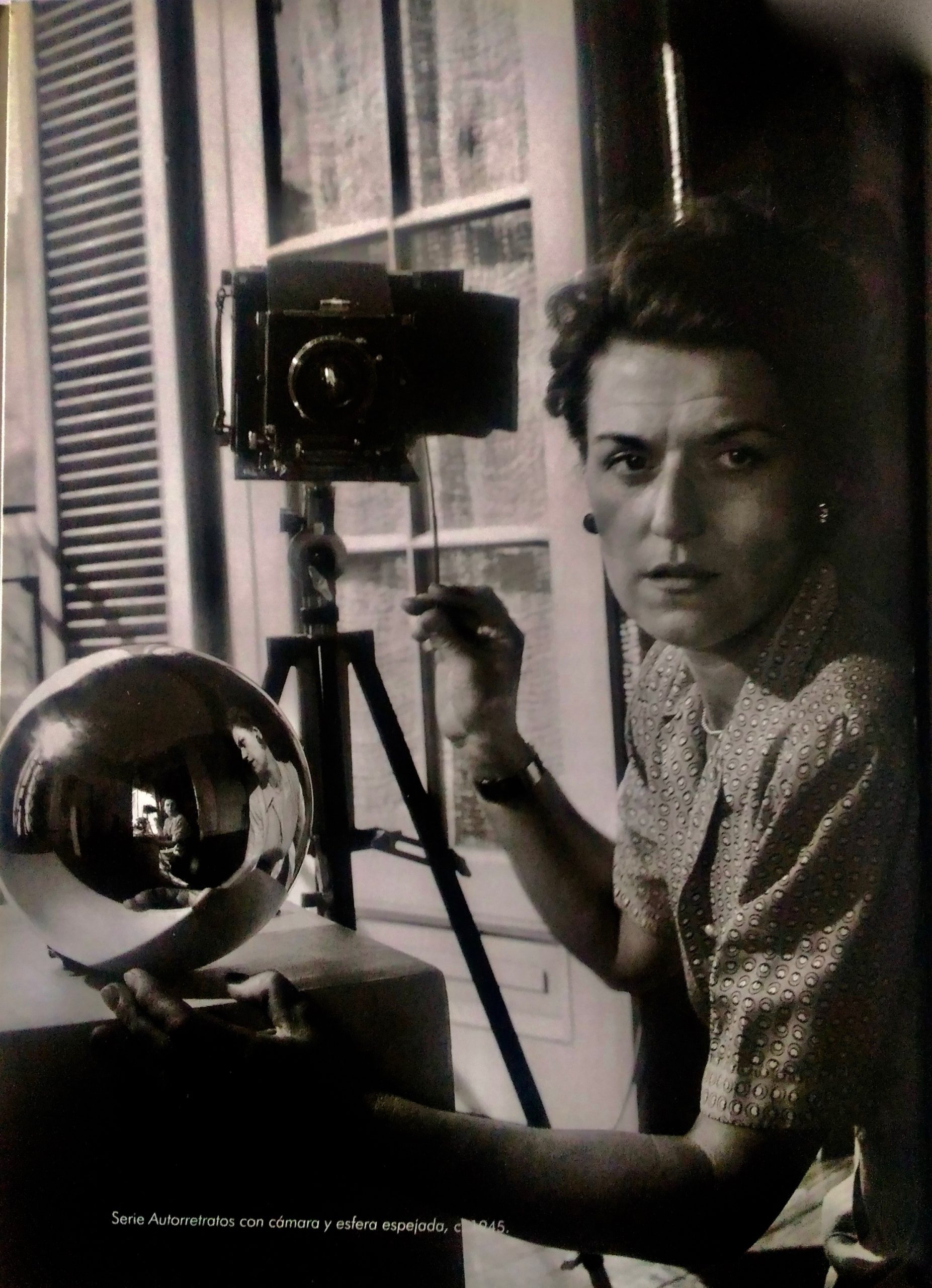

Born in Darmstadt, the German photographer Annemarie Heinrich arrived in Buenos Aires in 1926, at the age of 14. She received a camera from her uncle and taught herself to take photos. From Entre Ríos, where they first settled, the Heinrich family moved to Villa Ballester, on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. Once she moved to the city, Annemarie Heinrich was apprenticed by the Hungarians Rosa Kardofy, Rita Branger and Nicholas Shönfeld, the Australian Melita Lange and the Pole Sivul Wilensky. Through the Argentinian filmmaker Luis Saslavsky, she may have met well-known actors, singers and dancers. This led her to begin intense work on photographic portraits, which became very well known in the milieu. Indeed, in the 1940s, she established a photography studio for actors, dancers and intellectuals on Callao 1475 which is still open and now run by her children, Alicia and Ricardo Sanguinetti.

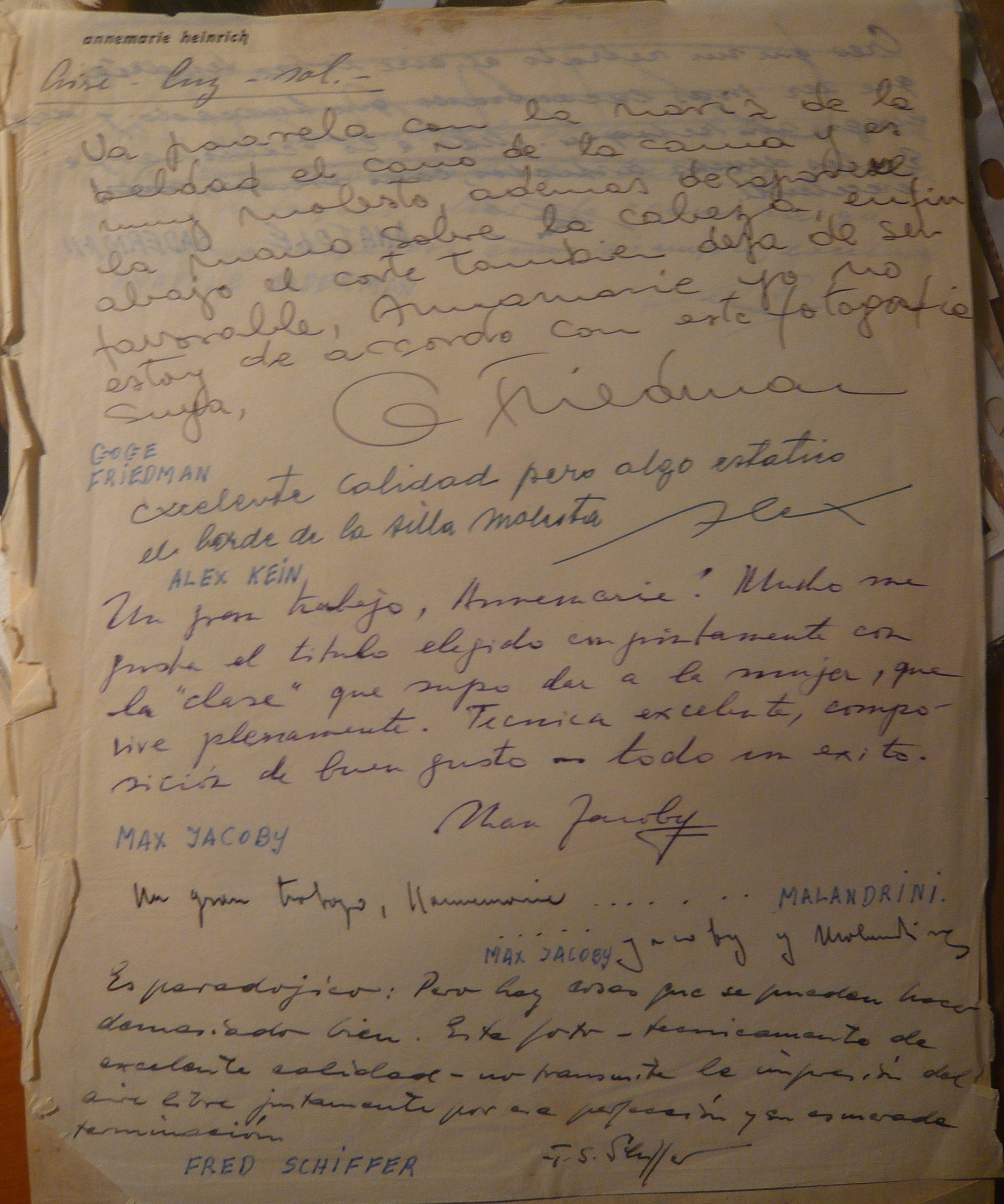

Annemarie Heinrich was a central member of La Carpeta de los Diez (The Folder of the Ten), an artistic group dedicated to advancing modern photography, active between 1953 and 1959. This cosmopolitan group brought together photographers from different backgrounds and geographies: Pinélides Aristóbulo Fusco, Eduardo Colombo, Augusto Valmitjana, Hans Mann, Max Jacoby, Giuseppe Malandrino, Juan Di Sandro, Georges Friedmann, Alex Klein, Ilse Mayer, Anatole Saderman, Fred S. Schiffer, Boleslaw Senderowicz.

Annemarie Heinrich, Self-Portrait with Camera and Mirror Sphere, c. 1945 (Wechsler 2015, 13).

The Folder of the Ten, year (© The Estate of Annemarie Heinrich, Buenos Aires).

07Victoria Ocampo’s house/ Rufino de Elizalde, 2831. Palermo chico

In a wealthy area of the Buenos Aires stands the house where Victoria Ocampo lived before she moved to Villa Ocampo in 1940. Surrounded by classic French style houses, the rationalist-architecture building located at Rufino de Elizalde 2831 immediately catches one’s attention because of its geometrical structure and its white colour. Following Ocampo’s firm instructions, the Argentinian architect Alejandro Bustillo designed three bright levels, fitted with large windows that connect to the outdoors by way of two balconies. Currently, the building houses the Casa de la Cultura del Fondo Nacional de las Artes, a public organisation that has supported cultural activities through grants since 1958.

Victoria Ocampo’s house in Palermo Chico (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2019).

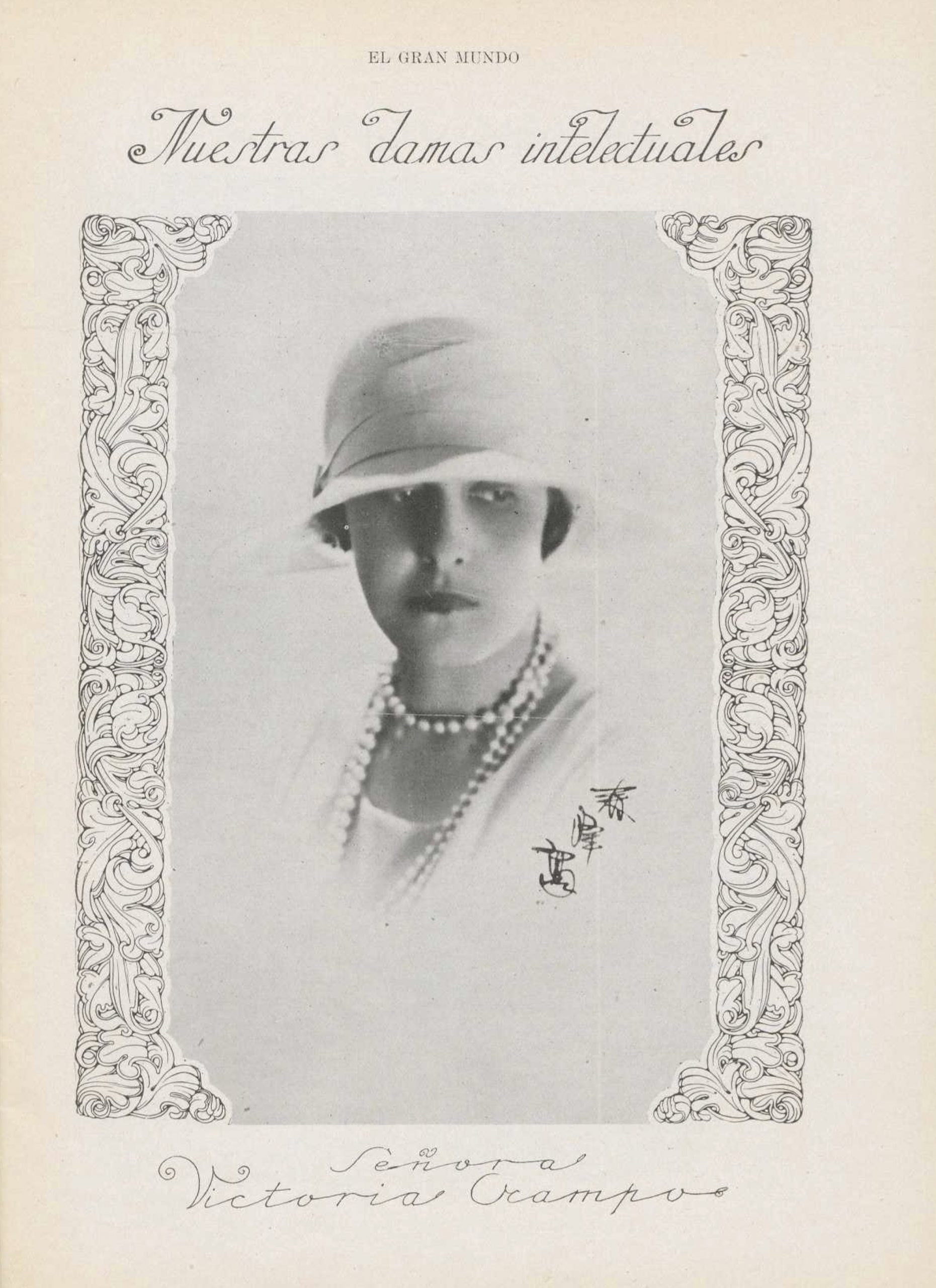

Growing up in a wealthy family, Victoria Ocampo received an extensive education. As a child, she became as comfortable speaking English and French as her native Spanish. She wrote mainly in French, and then translated some of her texts into Spanish herself. These language skills allowed her to get in touch with both the local and the foreign intelligentsia. For several years, she travelled through Europe with her family. In Paris, she met French writers, artists, and intellectuals, whom later she received at Villa Ocampo, her home in San Isidro. When she admired someone’s work, Ocampo would approach that person and include them in the circle that first met in her house in Palermo Chico and later on at Villa Ocampo. In 1936, together with the writers María Rosa Oliver and Susana Larguía, she founded and headed the Unión de Mujeres Argentinas (Argentine Women’s Union), through which she firmly opposed the Proyecto de 1936 to reform the Civil Code, which reintroduced gender inequality.

"Nuestras damas intelectuales. Señora Victoria Ocampo." El Gran Mundo. Revista Social y de la Moda, year 1, n. 1, 30 April 1928.

In 1931, Victoria Ocampo founded Sur, a literary magazine and a publishing house aligned with the anti-fascist cause, which — for almost two decades — was to become a major hub for intellectual exchanges in Buenos Aires. The close ties that Victoria Ocampo had with José Ortega y Gasset, a Spanish philosopher and writer, were decisive for the magazine’s identity. Ortega y Gasset had first travelled to Argentina in 1916 to give a series of lectures. Very soon he met Ocampo with whom he would maintain a lasting friendship. When Ocampo told Ortega y Gasset about her publication project, he was in Spain running the journal Revista de Occidente, which he himself had founded in 1923. The idea for the name for Ocampo’s magazine arose out of their close friendship and the spirit of creative collaboration: “It was chosen over the phone, across the Ocean. It seems that the whole Atlantic was needed for this baptism […].” (Victoria Ocampo, “Carta a Waldo Frank”, Sur, year 1, n. 1, january 1931, p. 14).

Sur, cover, n. 307, July-August 1967 (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo).

08Casa-museo Gyula Kosice/ Calle Humahuaca 4662, Almagro

On 4662 Calle Humahuaca stands the former house, now museum, of Gyula Kosice. Born into a Hungarian family in the Czechoslovak town of Kosice (now Slovakia), the four-year-old future artist reached Buenos Aires by ship in 1928. A pioneer of new art forms, and identifying himself with the concrete art movement, he brought together a group of artists who would exhibit their works at several events.

Gyula Kosice and his work, n.d. (© Fundación Kosice, Buenos Aires).

The first exhibition of the group Arte Concreto Invención was held at Enrique Pichón Rivière’s house, a Swiss-born psychologist from a French family; the second one at Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola’s house. One year later, Kosice left the group Arte Concreto Invención and, together with the Uruguayans Rhod Rothfuss and Carmelo Arden Quin, founded Arte Madí, a major avant-garde movement in Argentina, whose manifesto was read to the public at Galería Van Riel in 1946. Kosice asked the German photographer Grete Stern to design the logo for Arte Madí:

“From 1942, Grete took photos of my work, and a little later we began to hold the meetings of the Concrete Art-Invention Association in private homes, and one of them was in her place. Among other things, she took pictures of the members of the group. When I founded the group Madí I commissioned her to create a collage of the logo. I asked her to take a photo in front of the Obelisk, where there was an advertisement for the Movado watches, I was interested in the letter M of that poster, which was illuminated with neon gas, because at that time I was working with this material.” (Interview to Kosice, La Nación, 2 January 2000, https://www.lanacion.com.ar/cultura/una-pionera-de-la-fotografia-argentina-moderna-nid185096/)

Today, Kosice’s house has become a museum wide open to the public. It regularly offers activities for both children and adults. Moreover, Casa-museo Kosice offers visitors the possibility to see inside one of the traditional houses of the Buenos Aires Almagro district.

Grete Stern, MADI, photomontage, 1947, gelatin silver print, 59.8 x 49.4 cm. (© The Estate of Horacio Coppola, Grete Stern 1995, 48).

Grete Stern, Brochure for the exhibition El Movimiento de Arte Concreto Invención, 1945, Photomontage (© The Estate of Horacio Coppola, published in Bauhaus to Buenos Aires 2015, 32).

09Grete Stern & Horacio Coppola’s house/ Ex Calle Ascasubi 1173, Villa Sarmiento district, Morón (often attributed to Ramos Mejía)

At what is today Calle Hilario Ballesteros 1054 (Villa Sarmiento district) in Ramos Mejía, a suburb of Buenos Aires, you can still see the facade of the former home of the German photographer Grete Stern and the Argentinian photographer and film maker Horacio Coppola. The couple moved there in 1940 with their daughter Silvia. The Russian architect Vladimir Acosta was chosen for the construction of the building in 1939. Born in Odessa, Acosta had arrived in Buenos Aires in 1928. He was a close friend of Victoria Ocampo’s and it was probably her who helped him find a position in the studio of the architect Alberto Prebisch. For his friends Stern and Coppola, Acosta devised a modern house which stood out in all aspects from the surrounding buildings. Because of its style and building material — reinforced concrete and masonry — the house was called ‘the factory’. A two-storey atelier, the main space of Stern’s house, joins the ground floor with living spaces, and the first floor which contains the terraces, an office and a guest room. It really looked very different from other, more standard constructions built around the same time! The house was a meeting point for foreign artists and intellectuals, but also for Argentinians such as María Elena Walsh, Sara Facio and Jorge Luis Borges.

Grete Stern, Selfportrait, 1943, photograph, 21,9 x 30,5 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires.

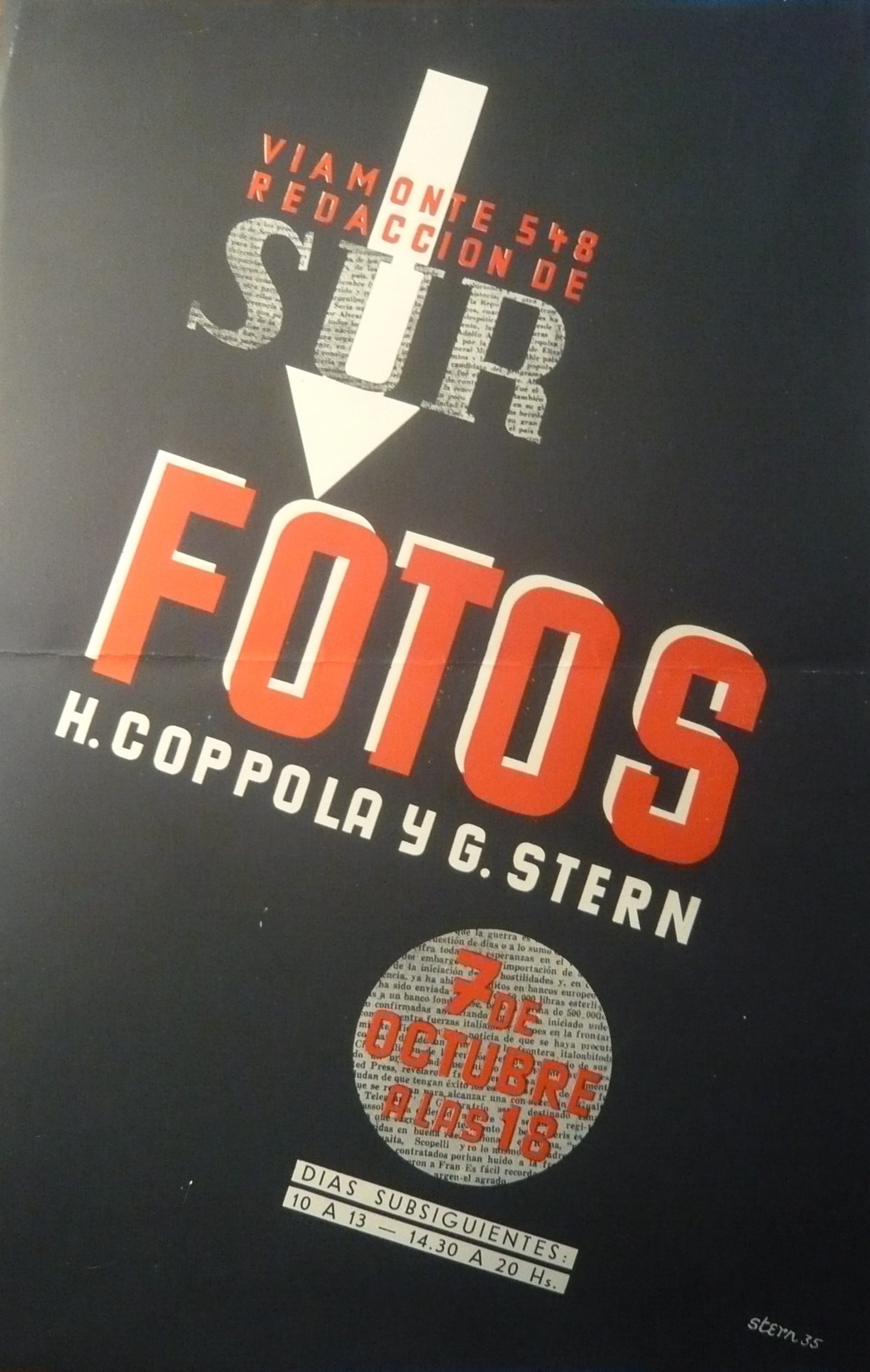

Stern and Coppola had met in Berlin in October 1932. Three years later, fleeing Nazi persecution, they decided to leave Europe for Coppola’s native Argentina. Stern’s integration into the cultural scene of Buenos Aires was facilitated by Coppola, her husband. When he left Argentina for Europe, he had already achieved recognition in Argentina for his photographic work, which was regarded as innovative and modern. Through Coppola, Stern met Victoria Ocampo who was surrounded by artists and writers, among them the Spanish painter, engraver and designer Luis Seoane, the Czechoslovak sculptor Gyula Kosice, the Austrian painter Gertrudis Chale, the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, Clément Moreau, the dancer Renate Schottelius, and the German photographer Annemarie Heinrich. Furthermore, it was at the Sur editorial headquarters — headed by Ocampo — that the couple Stern-Coppola exhibited their work for the first time in Argentina. This was in October 1935.

Grete Stern, Flyer exhibition Foto H. Coppola y G. Stern at Sur headquarters, 1935 (© The Estate of Horacio Coppola; courtesy of Carlos Peralta Ramos).

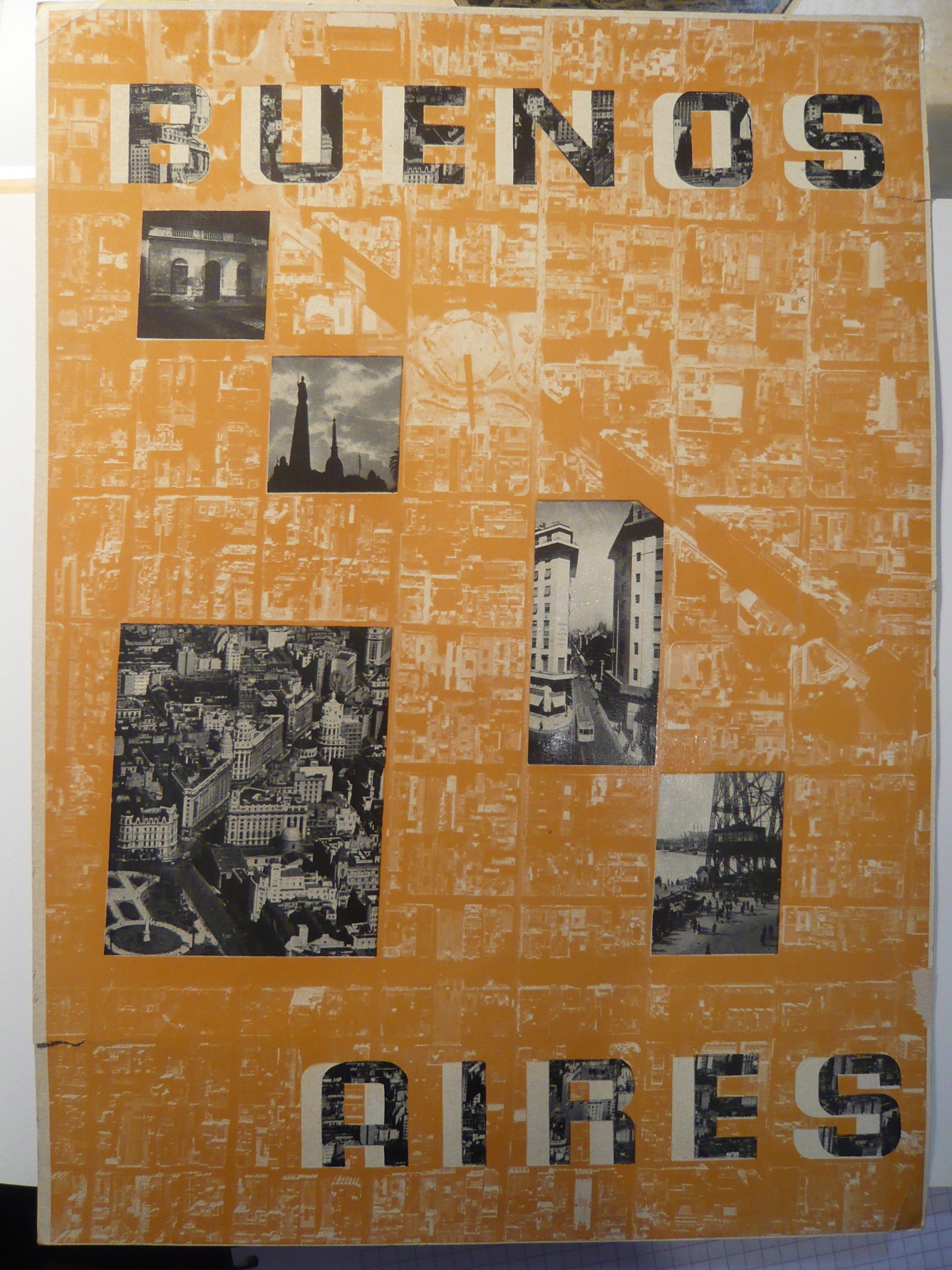

Grete Stern, cover for Buenos Aires: visión fotográfica por Horacio Coppola, 1937.

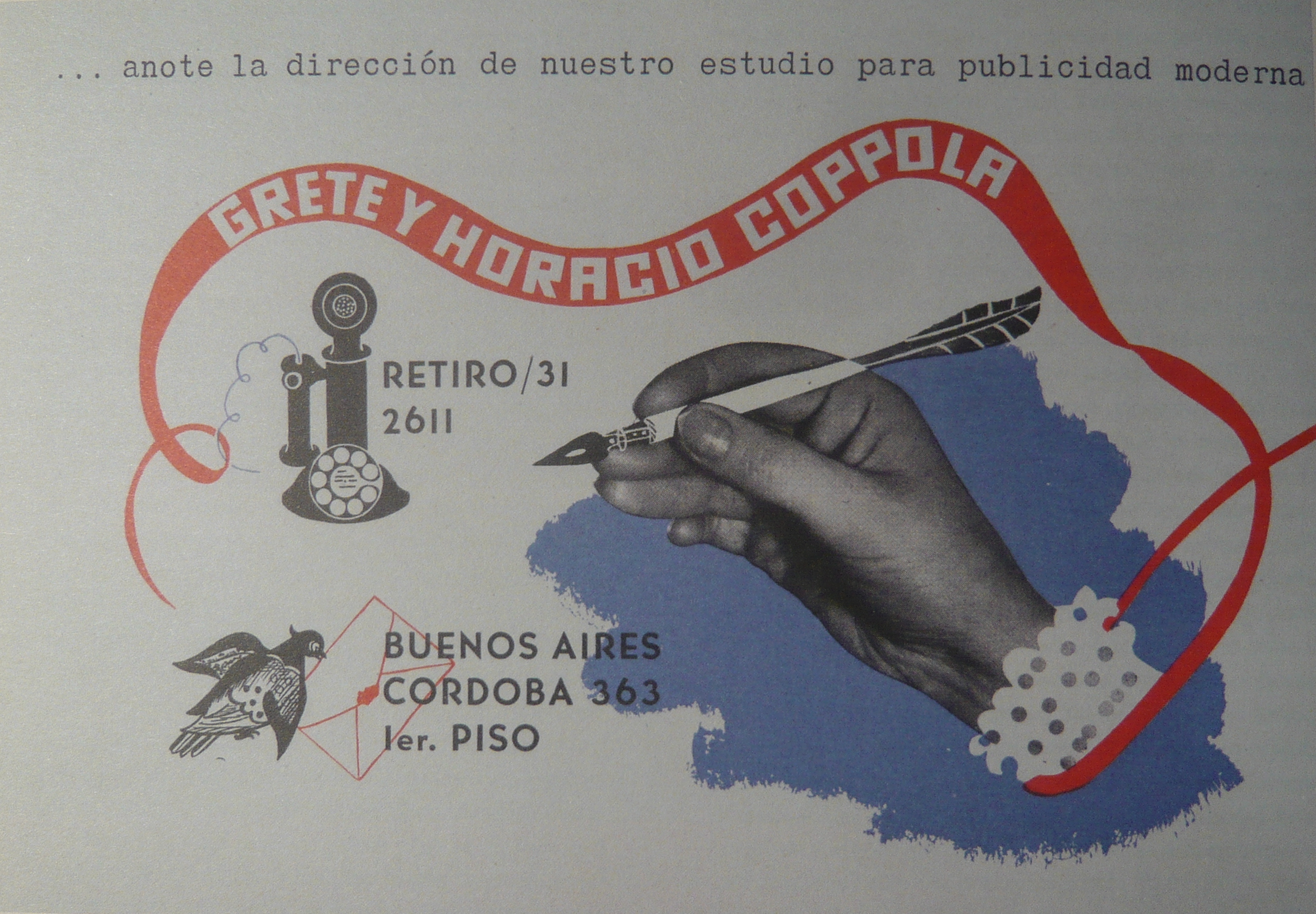

In 1937, together with Seoane, the couple opened a photography studio at Avenida Córdoba 363 which specialized in advertising and which eventually had to close two years later due to a low demand for the type of advertising products they offered. Despite this, Grete Stern was by then already fully integrated into the Argentinian artistic and cultural scene. She would continue in the same way as Ocampo, gathering and providing space for exchange to the European intellectual diaspora in her house in Ramos Mejía.

Brochure of Stern-Coppola’s advertising studio in Avenida Córdoba 363 (© The Estate of Horacio Coppola).

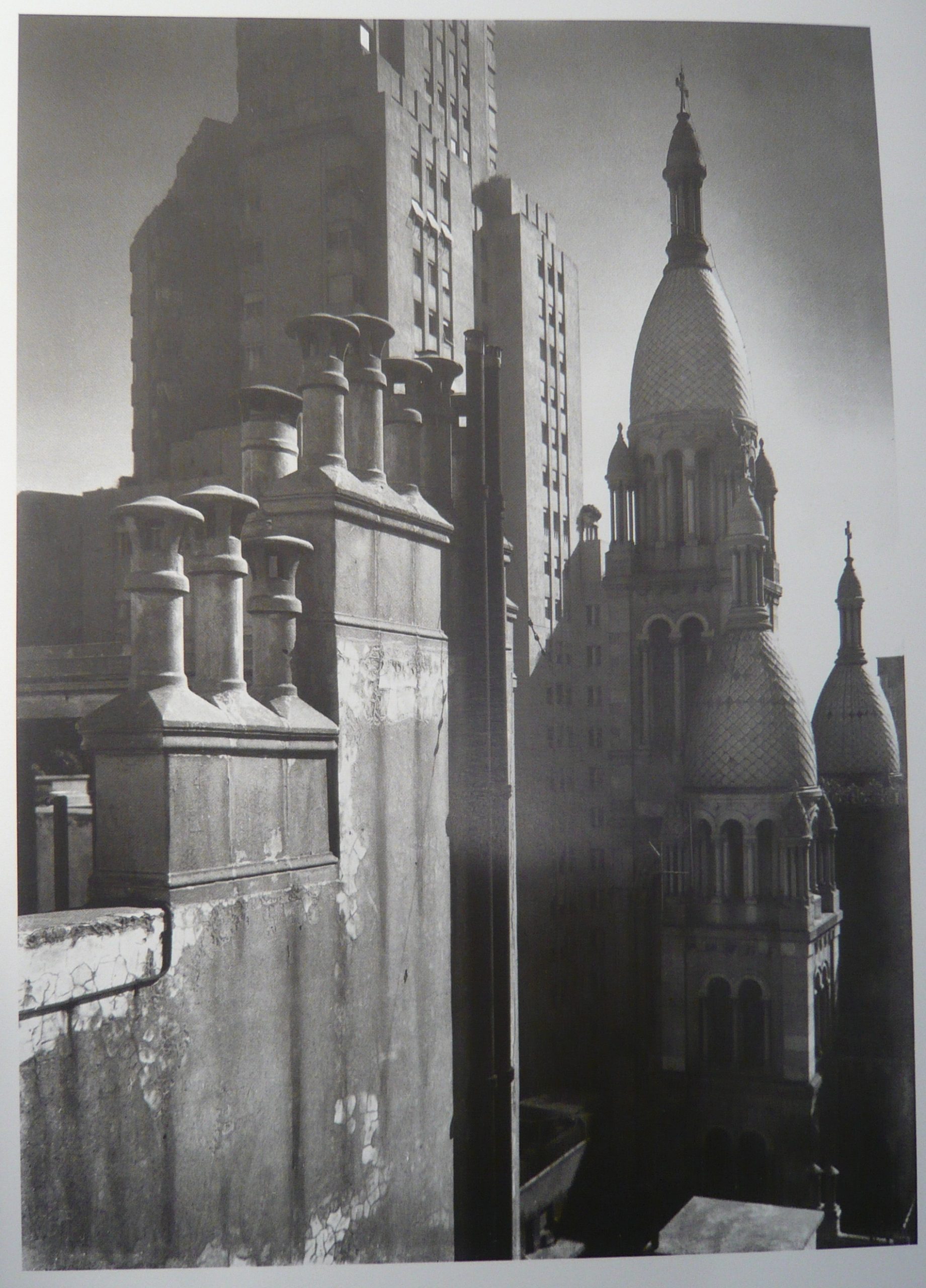

Grete Stern took this photo from a high point that allowed her to capture the Kavanagh Building erected on Florida 1065 by the Argentine architecture studio Sánchez, Lagos y de la Torre in 1936. With its 120 meters, the building was then the tallest concrete building in all of Latin America. The photograph also shows the Holy Sacrament Church which is located diagonally to the Kavanagh Building.

Grete Stern, Holy Sacrament Church and Kavanagh Building, Buenos Aires, 1951/52 (Príamo 1995, 80).

10Villa Ocampo/ Calle Elortondo 1837, Beccar, San Isidro

Twenty-five kilometres from Buenos Aires, following the river Río de la Plata to the North, stands Villa Ocampo. Its last owner was Victoria Ocampo (1890–1979), the Argentinian intellectual, writer, publisher and founder of Sur magazine. Located at Elortondo Street 1837, Villa Ocampo was built in 1890 in San Isidro as the family’s summer residence. Manuel S. Ocampo, Victoria’s father, constructed the house while living in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires with his family. The house was equipped with the most modern comforts: electric light both in the house and the garden thanks to an electric generator, a modern hydraulic system, and an elevator between the ground floor and the first floor. Victoria Ocampo moved back to this house where she had spent her childhood, after inheriting it from Francisca Ocampo de Ocampo “Tia Pancha”, her godmother, in 1941.

Grete Stern, Holy Sacrament Church and Kavanagh Building, Buenos Aires, 1951/52 (Príamo 1995, 80). Villa Ocampo, outside view (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2018).

The 700 square meter house stands on a 1.12-hectare plot. Formerly, when the Ocampo family spent their summers here in the first decades of the 20th century, the land extended over 15 hectares. Before passing into Victoria’s hands, the plot was divided, shaping it into the area it is today. Villa Ocampo combines French and Victorian style architecture and has four levels: the basement, the ground floor, the first floor and a higher level, invisible from the interior of the house, where the service personnel were housed (cooks, butlers, gardeners). Currently, the library and the administration of the house are accommodated there. Victoria combined the rustic with the modern, the classic with art deco. Bauhaus-style lamps purchased in Europe illuminate the rooms that contain antique chandeliers and armchairs, as well as 18th-century Chinese furniture brought from Paris. Her collection of 12,000 books is to be found scattered throughout the rooms, the desks and the library.

Grete Stern, Holy Sacrament Church and Kavanagh Building,Buenos Aires, 1951/52 (Príamo 1995, 80). Villa Ocampo, living room (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2018).

The elegant facade is complemented by loggias, balconies and terraces which connect the house to the outside. The garden, which formerly descended through a ravine to the river, was full of rich vegetation and sculptures, and featured a pavilion and a lake with swans. This connection to the water through the lake and the river was lost when the plot was divided.

Many illustrious visitors spent time here. Among dozens of intellectuals who surrounded the writer counted Indira Gandhi, Julio Cortázar, André Malraux, Rabindranath Tagore, Gabriela Mistral, Igor Stravinsky, José Luis Borges and Attilio Rossi. Several exiled artists were part of Victoria Ocampo’s circle: Gyula Kosice, Gisèle Freund, Grete Stern, Luis Seoane and Clément Meffert, among many others. Thus, a wide network of local and foreign artists and intellectuals regularly met in Victoria Ocampo’s country house.

In 1973, Victoria Ocampo donated the house with its garden to UNESCO with the aim of preserving it as a cultural place. Since then, the house has hosted international meetings and celebrations, such as those of the first ladies of the G20. Villa Ocampo is a testimony to the tastes and customs of both high society and intellectuals in Buenos Aires in the first half of the 20th century, and an important contribution to preserve the memory of networks between local and immigrant artists.

Villa Ocampo, garden (Photo: Laura Karp Lugo, 2018).

Acknowledgements

My deepest thanks go to Diana B. Wechsler, Luis Príamo, Leonor Martínez, Alejandro Saderman, Alicia and Ricardo Sanguinetti (Estudio Heinrich Sanguinetti), Carlos Peralta Ramos (Archivo Grete Stern), Paula Hrycyk, Milena Gallipoli, Max Pérez Fallik (Museo Kosice), and the librarians and archivists of the Archivo General de la Nación, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, the Museo de Arte Moderno, the Museo Sívori, the Fundación Espigas, the Archivo del Instituto de Investigación en Arte y Cultura “Dr. Norberto Griffa”, and Iván Buenos Aires (Asociación Art Nouveau Buenos Aires).

Bibliography (selection)

Baldasarre, María Isabel. “Terreno de debate y mercado para el arte español contemporáneo: Buenos Aires en los inicios del siglo XX.” La memoria compartida: España y la Argentina en la construcción de un imaginario cultural (1898–1950), edited by Yayo Aznar and Diana B. Wechsler, Paidós, 2005, pp. 109–132.

Baldasarre, María Isabel. Los dueños del arte: coleccionismo y consumo cultural en Buenos Aires. Edhasa, 2006.

Berjman, Sonia. La Victoria de los jardines. Papers Editores, 2007.

Bertúa, Paula. “Devenires de una artista migrante: el destino argentino de Grete Stern.” IAHMM Revista de Historia Bonaerense, year XXIII, no. 46, 2017, pp. 6–14.

Blancpain, Jean-Pierre. Les Européens en Argentine: immigration de masse et destins individuels, 1850–1950. L’Harmattan, 2011.

Borghini, Sandro, and al., editors. 1930-1950. Arquitectura moderna en Buenos Aires. Ed. Nobuko, 2012.

Buenos Aires 1936: visión fotográfica por Horacio Coppola. Municipalidad de Buenos Aires, 1937.

Comisión Nacional del Censo and Alberto B. Martínez, editors. Tercer censo nacional levantado el 1 de junio de 1914: Ordenado por la ley 9108. Talleres gráficos de L.J. Rosso y Cía, 1916.

Coppola, Horacio. Imagema: Antología Fotográfica 1927–1994. Fondo Nacional de las Artes, 1994.

Devoto, Fernando. Historia de la Inmigración en la Argentina. Editorial Sudamericana, 2003.

Facio, Sara. “La fotografía argentina (1920–1950)”, Historia general del arte en la Argentina, t. VII, Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1995.

Gruschetsky, Valeria Ana. “El espíritu de la calle Corrientes no cambiará con el ensanche”. La transformación de la calle Corrientes en avenida. Debates y representaciones, Buenos Aires 1927–1936 (master thesis). Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2007.

Gutierrez Viñuales, Rodrigo. “Arte y decoración en la obra de Andrés Kálnay”. El arquitecto Andrés Kálnay, CEDODAL, 2002, pp. 59–72.

Karp Lugo, Laura. “L’art espagnol de l’Europe à l’Argentine: mobilités Nord-Sud, transferts et réceptions (1890–1920). ” Artl@s Bulletin, vol. 5, no. 1, article 4, pp. 38–49. Online since 13 June 2016, http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas/vol5/iss1/4.

Karp Lugo, Laura. Interview with Alicia Sanguinetti. (Studio Annemarie Heinrich, Buenos Aires, 2018).

La gran ilusión: vida cotidiana en Villa Ocampo durante la Belle Époque. Asociación amigos de Villa Ocampo, 2013.

Lanuza, José Luis. Pequeña historia de la calle Florida. Cuadernos de Buenos Aires, V. Municipalidad de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, 1947.

Marcoci, Roxana. “Photographer Against the Grain: rough the Lens of Grete Stern.” From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola, edited by Roxana Marcoci and Sarah Hermanson Meister, exh. cat. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2015, pp. 21–36.

Meo Laos, Verónica Gabriela. Vanguardia y renovación estética: Asociación Amigos del Arte (1924–1942). Ediciones CICCUS, 2007.

Ocampo, Victoria. Autobiografía I. El archipiélago, Sur, 1979.

Ocampo, Victoria. Autobiografía II. El imperio insular, Sur, 1980.

Ocampo, Victoria. Autobiografía III. La rama de Salzburgo, Sur, 1981.

Príamo, Luis. “La obra de Grete Stern en la Argentina.” Grete Stern: Obra fotográfica en la Argentina, exh. cat. Museo de Arte Hispanoamericano Isaac Fernández Blanco, Buenos Aires, 1995.

Rinaldini, J. “Notas. Crítica de Arte. Experiencia de una exposición de arte.” Sur, no. 22, July 1936, pp. 92–94.

Rivera, Jorge B. Madí y la vanguardia argentina. Ediciones Paidós, 1976.

Romero Brest, Julio. “Fotografías de Horacio Coppola y Grete Stern.” Sur, no. 13, October 1935, pp. 91–102.

Saderman, Anatole. Secretos del jardín. Vasari, 2009.

Wechsler, Diana B. Estrategias de la mirada: Annemarie Heinrich, inédita. Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, 2015.