Bombay

Cosmopolitan Exile: Creative Movements in a Shifting City

“Among the truths Bombay holds to be self-evident is the fact that it is cosmopolitan” writes Naresh Fernandes (2013, 57) in City Adrift. Another truth about the dense urban fabric of Bombay seems to be its potential for openness. In the period explored in this walk – roughly the two decades that bracketed Indian independence – there was a spirit of new beginnings in the air. The European creatives who emigrated to Bombay at that time, mostly due to Nazi persecution, enriched and stimulated the local cultural scene. This walk offers insights into places where exile (hi)stories intersected with local cultural production. It explores sites where transcultural dialogues led to the emergence of plural networks and new infrastructures within the informally organised artscape that had developed in parallel with, and perhaps in spite of, somewhat calcified colonial-era institutions. The walk reveals Bombay’s cosmopolitan openness, and some of its contradictions as well.

miles 160

min. 10

sights By foot

1The Taj Mahal Palace Hotel and Green’s Hotel/ Apollo Bunder

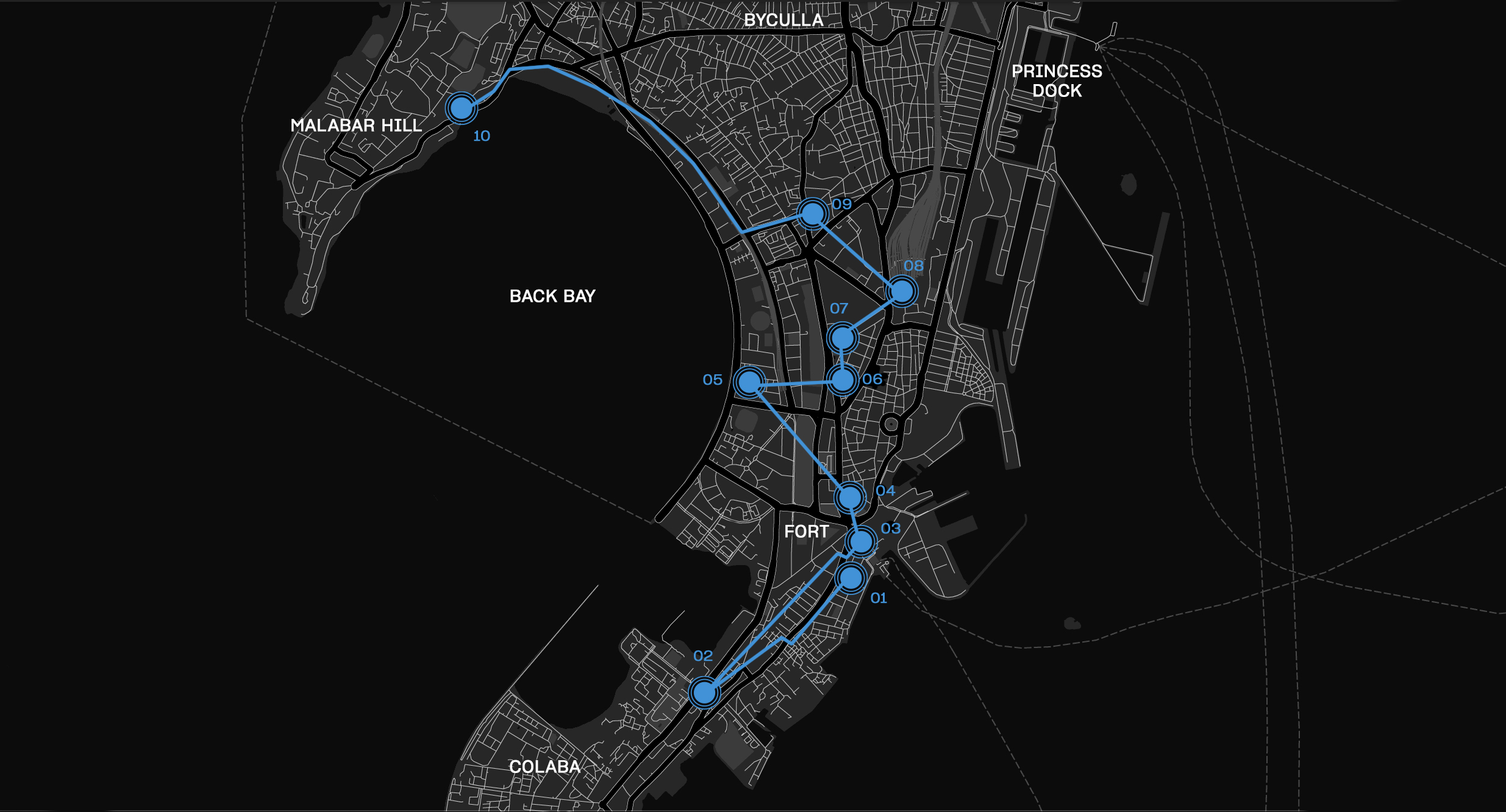

For exiles arriving in Bombay by ship, the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel (or the Taj, as it is affectionately known) was one of the first buildings they saw. Sitting solidly on Apollo Bunder, built of grey stone and articulated by an array of white bay windows and domes, the Taj’s opulent architecture dominated the approaching cityscape.

Postcard “Bombay. from Harbour” showing the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel from the Arabian Sea, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

View of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel and Apollo Bunder, 2019 (© Rachel Lee).

Postcard “The Taj Mahal Hotel”, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

The author Louis Bromfield describes the scene from a ship approaching Bombay (Bromfield 1946, 13).

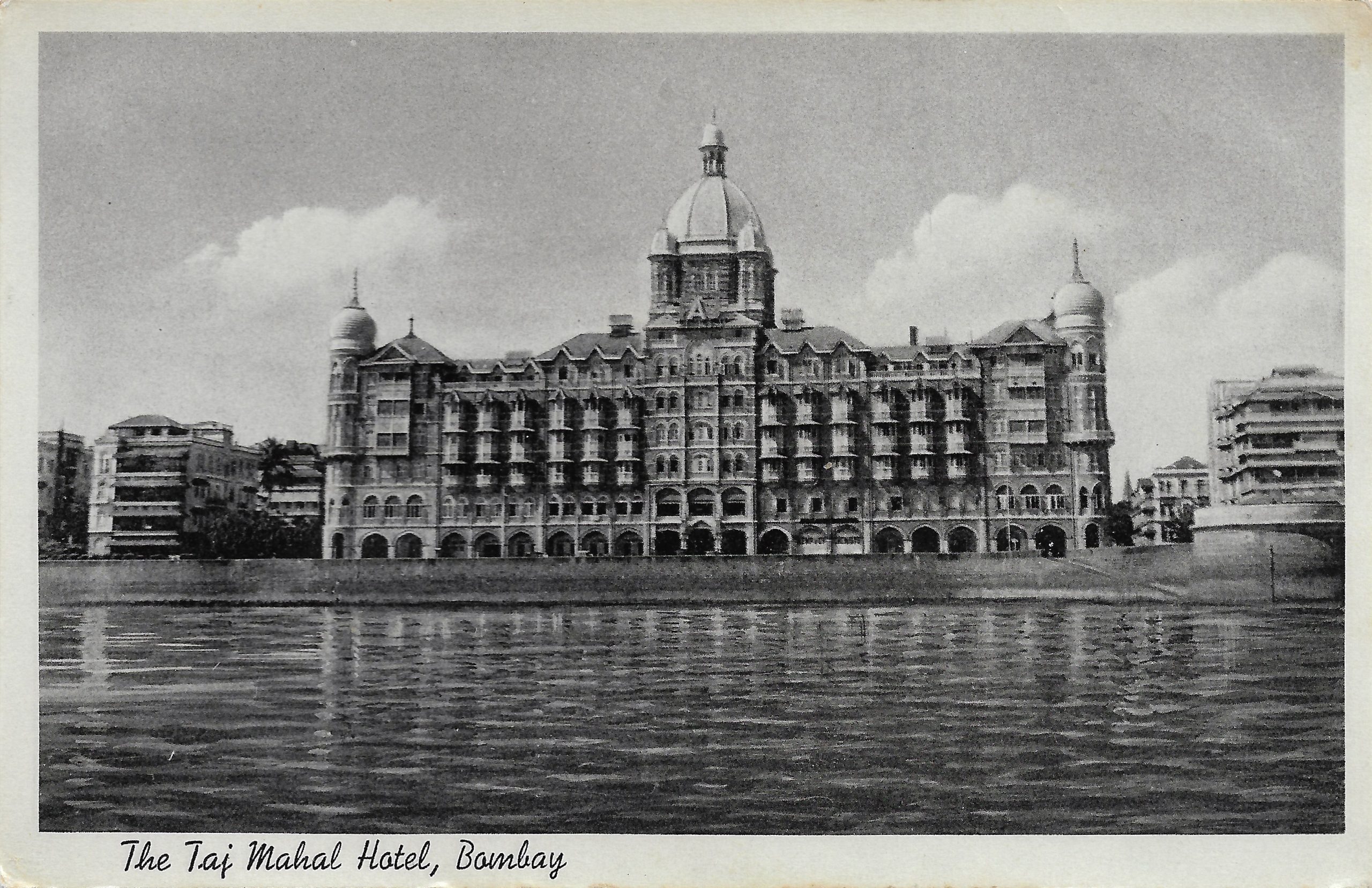

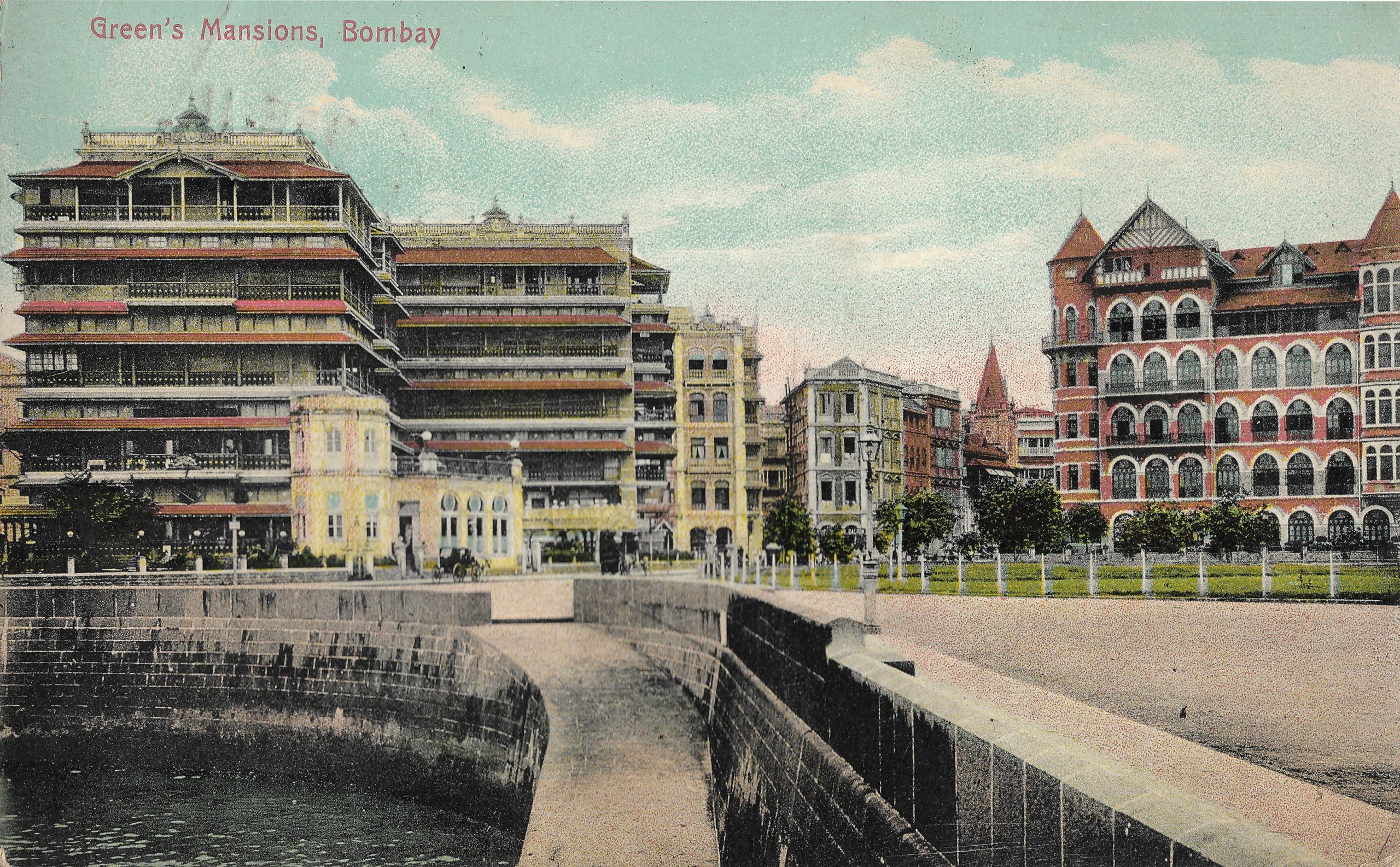

On an adjacent site to the north of the Taj, where the Taj Tower now stands, was another, considerably less eye-catching and much smaller hotel – Green’s. Working reciprocally, these contrasting hotels provided important spaces of sociability for exiled artists and Bombayites.

Postcard “Green’s Mansions, Bombay”, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

Postcard “Green’s Mansions, Bombay”, n.d (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

Postcard “Taj-Mahal Hotel, Bombay” showing Green’s Hotel on the right, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

Description of the Taj and Green’s from Ben Diqui’s Bombay guidebook (Diqui 1927, 20f.).

Commissioned by the Parsi industrialist J.N. Tata and opened in 1903, the commodious, luxurious Taj was a milestone in India’s hospitality history. For many visitors, particularly the wealthy, it was the hotel in Bombay. Green’s, built as mansion flats by William Boyd Green in 1890, was purchased by the Tata Group and was operated as part of their Indian Hotels Company Ltd. in tandem with the Taj from 1904.

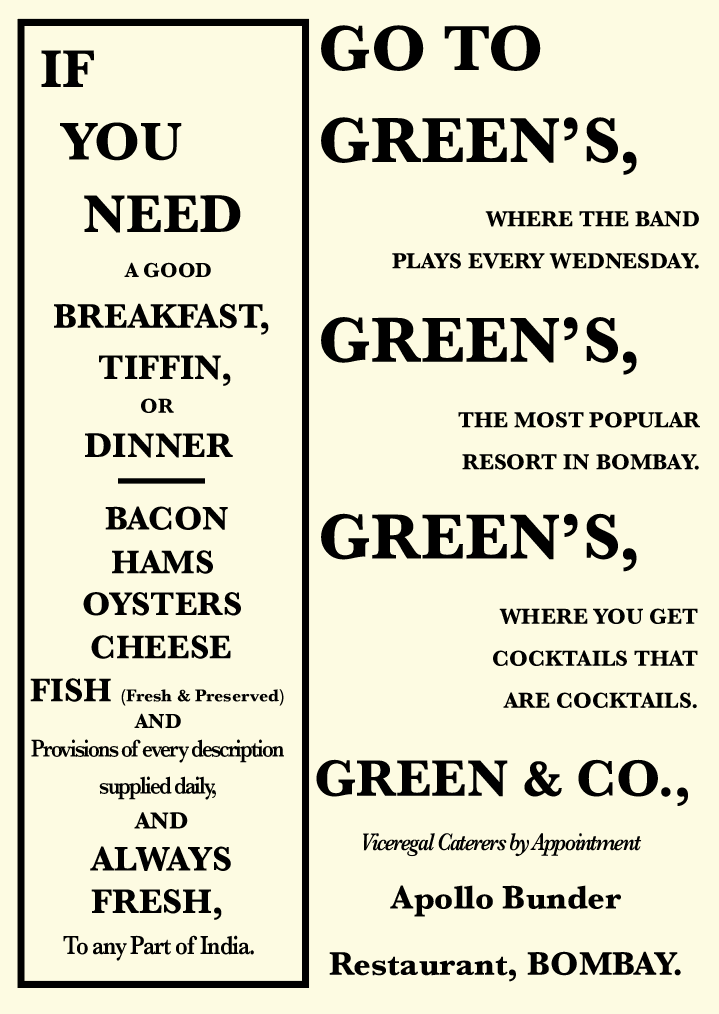

Though under the same management, the Taj and Green’s remained outwardly distinct, following different agendas in terms of the entertainment they offered and the type of clientele they wished to attract. Where the Taj was the epitome of aspirational manners and sophisticated socialising, Green’s was impolite, loud and subversive. Both hotels were venues for local cultural and social life: as well as dances and dinners, they hosted classical music and jazz performances, political meetings and conferences, and exhibitions. For the local and exiled artistic communities, they were places to meet, exchange and present their work – formally and informally.

Partying on Green’s newly refurbished terrace, n.d. (Courtesy Tata Central Archives).

Dancing in the Taj’s ballroom, n.d. (Courtesy Tata Central Archives).

Cabaret at the Taj, n.d. (Courtesy Tata Central Archives).

Louis Bromfield describes the scene at Green’s in Night in Bombay (Bromfield 1946, 8).

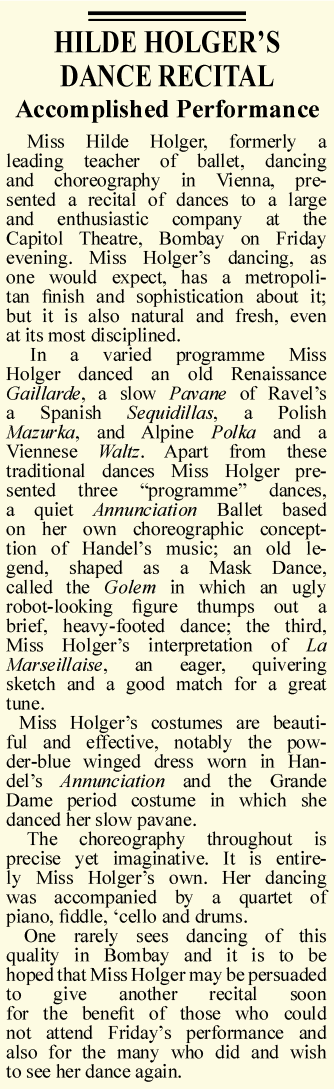

Hilde Holger, the exiled Viennese expressionist dancer, gave her first public performance in the Taj in 1938. The Austrian painter Walter Langhammer and the Bohemian composer and musician Walter Kaufmann both lectured at the Rotary Club’s regular luncheon meetings at Green’s, as did the author Mulk Raj Anand and the art collector and physicist Homi Bhabha. The All-India Association of Fine Arts met at Green’s, while Kekoo Gandhy, founder of Gallery Chemould, curated exhibitions in the Taj: K.K. Hebbar’s work was shown in the Princes’ Room. Gandhy also showed art in a ‘window’ in the hotel. As art critic for The Times of India, Rudi (Rudolph) von Leyden reported on these shows to the English-speaking, newspaper-reading public.

The exiled artists probably lunched with local artists on Green’s spacious terrace, danced to the jazz music played by Teddy Weatherford’s band in the first-floor ballroom, and enjoyed drinks together at the famously long bar.

Advertisement for Green’s (The Times of India, 16 June 1904, 7).

Report of a fight at Green’s (The Times of India, 14 April 1948, 8).

Entertainment at the Taj and Green’s (The Times of India, 8 April 1938, 4).

Rudi von Leyden lecturing on art at Green’s (The Times of India, 5 May 1936, 3).

Jazz at the Taj and Green’s (The Times of India, 30 October 1941, 10).

Despite their differences, the Taj and Green’s were complementary. What may have appeared to other hotel managers as an undesirable co-existence, the Tatas viewed as an asset. The two hotels continued to function side-by-side in their contrasting ways until Green’s was demolished to make way for the Taj’s extension, the 21-storey Taj Tower, which opened in 1973. While no doubt serving to increase the Taj’s profits, this streamlining of the business erased a site of the city’s cosmopolitan history.

02Jassim House (Taraporewala Mansion)/ 25 Cuffe Parade (Today: Captain Prakash Pethe Marg)

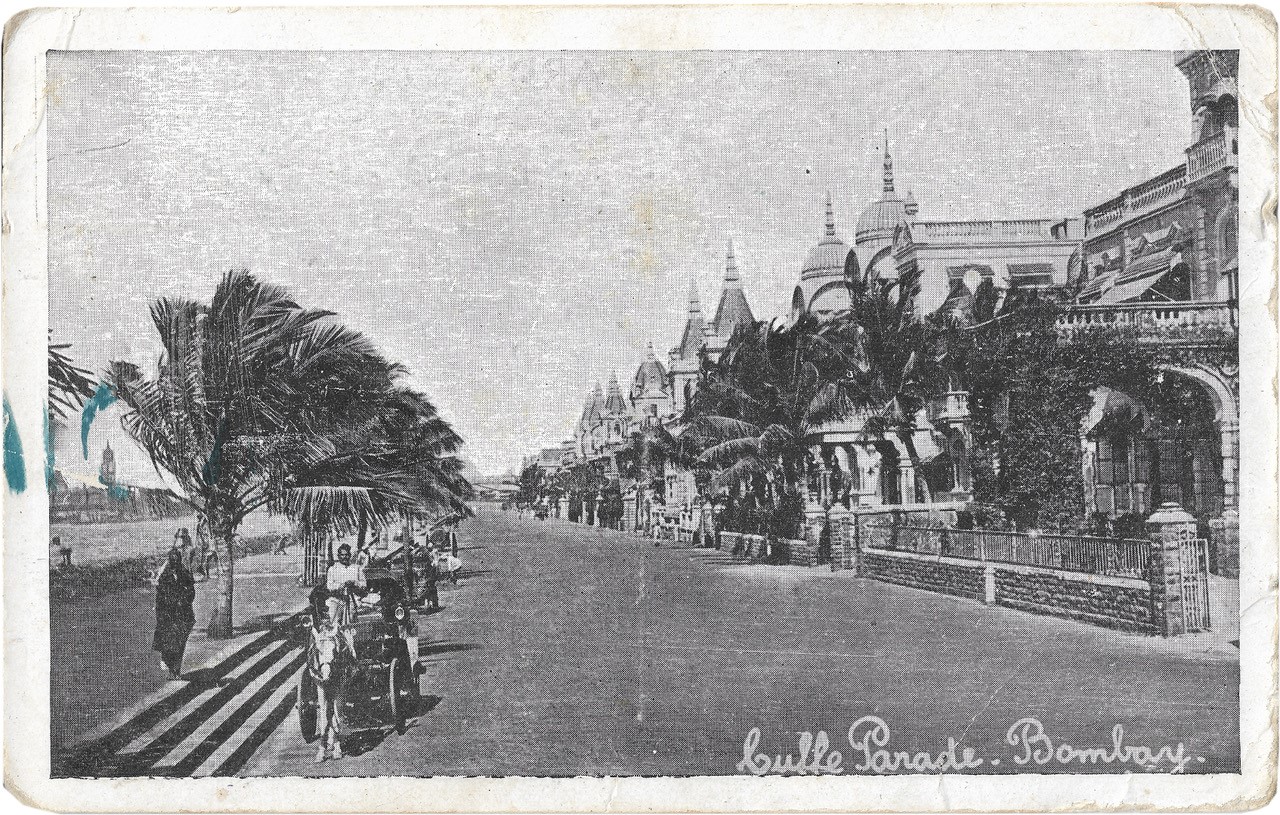

Taking in the view of the Arabian Sea, a twenty-minute walk from the Taj, lies Cuffe Parade. The sea-side promenade is part of the wealthy Colaba precinct bordering the Fort area in the south of Mumbai. At number 25, recognizable from afar thanks to its decorated twin domes and multifoile arches, is Jassim House, also known as Taraporewala Mansion.

Postcard “Cuffe Parade. Bombay”, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

It is the former residence of several key figures of Bombay’s 1940s cultural scene: the De Silva Sisters from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), who were joined by the writer-activist Mulk Raj Anand in 1945. Anand had already become a crucial voice in Indian English literature in London, where he initially met Anil De Silva. Both not only participated in the independence movements of their countries of origin, but also shared a passion for art and architecture. The same applies to the younger sister Minnette De Silva, who was educated at the Sir J.J. College of Architecture in Bombay as well as the Architectural Association in London.

Just as the group cultivated a diverse network in London, their shared apartment in Colaba became a transcultural contact zone for local and exile protagonists of Bombay’s cultural sphere. Homi J. Bhabha and Kekoo Gandhy were among their regular guests. Likewise, the exile circle around Rudi von Leyden, the artist couple Walter and Käthe Langhammer, and collector Emmanuel Schlesinger visited regularly. The fact that 25 Cuffe Parade was already in itself an open-minded space is demonstrated not least by the other dwellers of the house. From 1933 to 1970 the Jewish-Muslim Hamied family led a secular life there. With their legendary parties, Luba Derczanska (from Lithuania) and Khwaja Abdul Hamied fostered exchange among Hindus, Muslims and Jews alike.

Pablo Picasso (left), Minnette De Silva, Jo Davidson and Mulk Raj Anand at the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace, 1948 (PAP, Public Domain, via Wikipedia Commons).

Certainly, the exchange was not hindered by the environment in which it unfolded. Surrounded by tropical plants and framed by deep verandas, the villa is characterised by an eclectic architectural mix typical for Bombay during the British Raj. Often classified as “Indo-Saracenic”, it combines contemporary colonial tropes with indigenous Indian building elements. Crafted, floral ornaments in the glazing and the intricate facade design, which was informed by Mughal and Sikh architecture, contrast with more minimalist exterior tilework in grey-blue.

Historic image of Jassim House, built around 1900 (Gupta 1986, 227).

Jassim House at 25 Cuffe Parade, 2018 (© Rachel Lee).

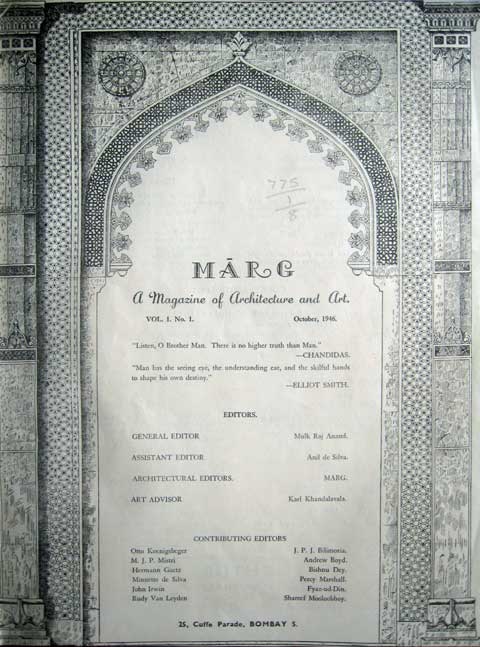

The in-betweenness of the architecture seems to correspond with the political situation of the era. After the Indian Rebellion in 1858, India had lost even more rights to the British crown. However, in the 1940s postcolonial independence was in sight. It was against this horizon that the Modern Architectural Research Group was brought into being in 25 Cuffe Parade in 1946. Within these walls, the concept for an Indian modernity was shaped in the form of a quarterly magazine on architecture and art: Marg.

Editors’ page, Marg , vol. 1, no. 1, 1946 (© The Marg Foundation/ MARG archive).

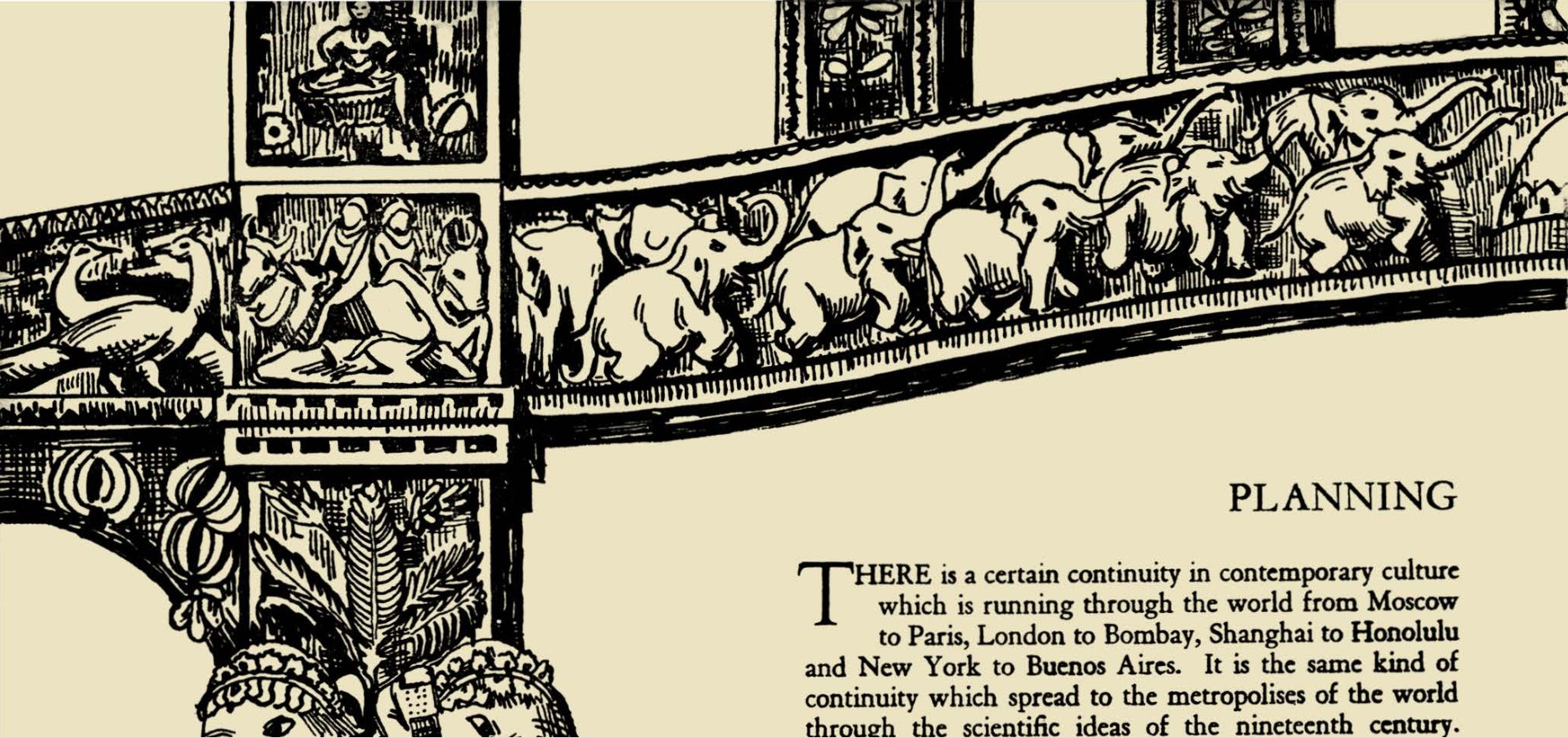

Editorial “Planning and Dreaming.” Marg , vol. 1, no. 1, 1946. (© The Marg Foundation/ MARG archive).

Cover of Marg , vol. 1, no. 1, 1946 (© The Marg Foundation/ MARG archive.)

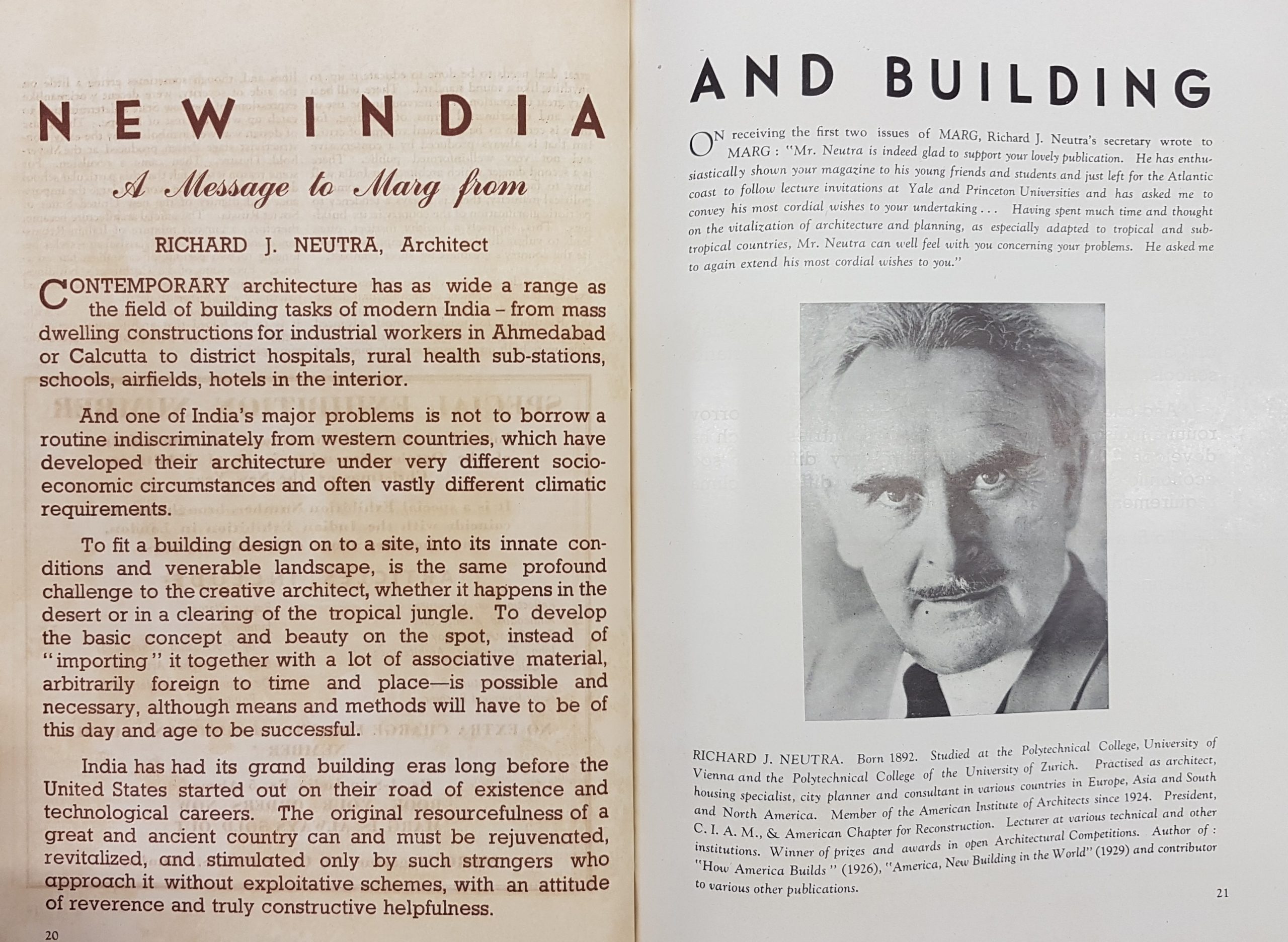

Article “A message to Marg from Richard J Neutra.” Marg , vol. 1, no. 4, 1947 (© The Marg Foundation/ MARG archive).

Editorial “An approach to Modern Indian Architecture by Andrew Boyd.” Marg , vol. 3, no. 2, 1949 (© The Marg Foundation/ MARG archive).

Among the fourteen founding members were Mulk Raj Anand, Anil and Minette De Silva as well as the German exile architect Otto Koenigsberger. According to Minnette De Silva’s autobiography the German art historian Hermann Goetz as well as the Indian architects Minoo Mistry and J.P.J. Billimoria were also involved in MARG. The magazine dedicated itself to reviewing classical and contemporary cultural production which included foreign and Indian art, architecture, clothing, crafts and dance. In his first editorial for MARG titled “Planning and Dreaming” Anand wrote: “…we hope that all the problems of beauty in construction, design, function and human value will be posed in MARG” (Anand 1946, 4).

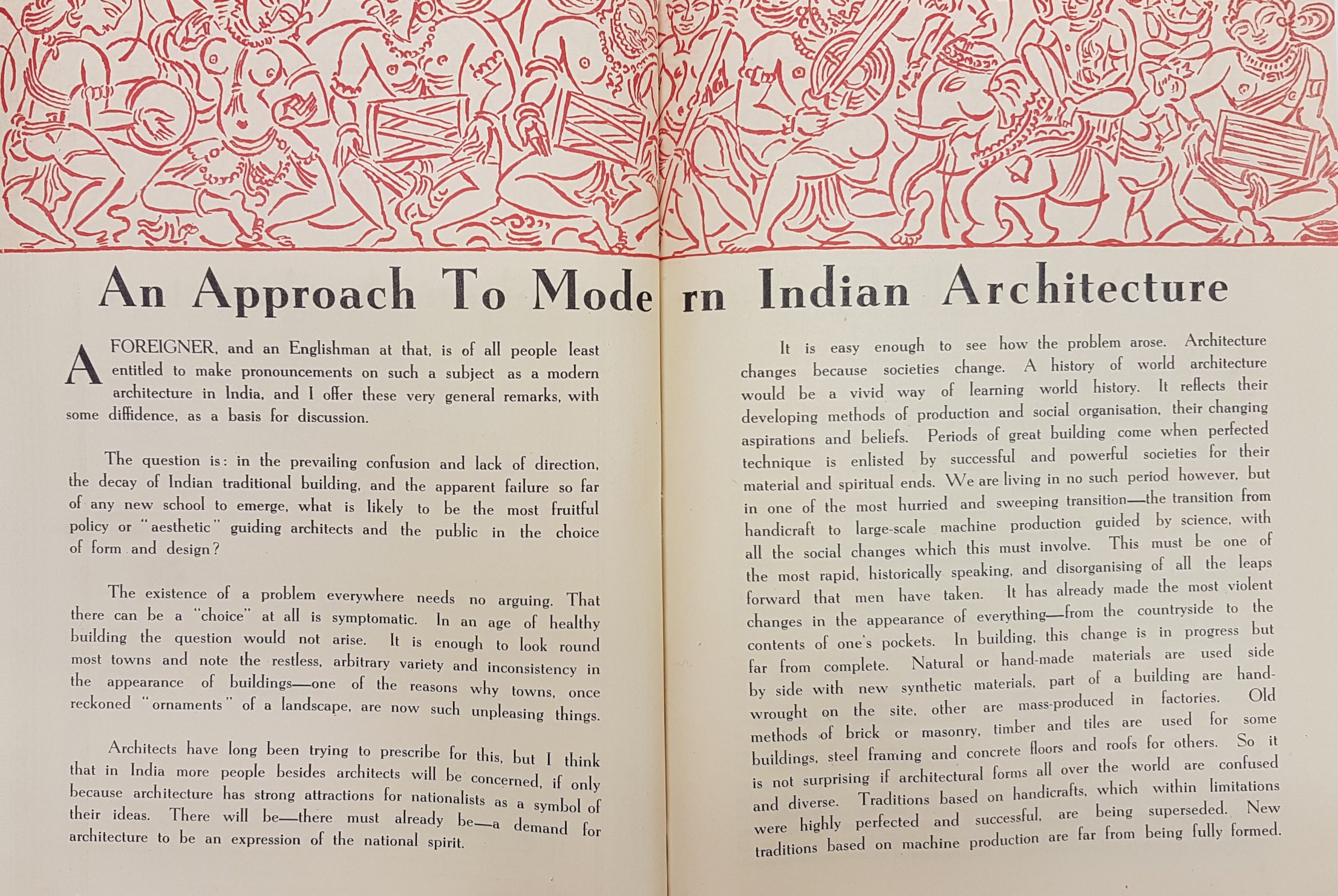

Mulk Raj Anand with George Keyt paintings at his home Jassim House, 25 Cuffe Parade, 1950s. Photographer unknown (Garimella, 2005, 9 © The Marg Foundation/ MARG archive).

The vision of the interdisciplinary team encompassed an innovative orientation of current practice while also preserving the region’s cultural heritage in the process of nation building. However, Marg published examples of modern architecture by Indian architects on a much smaller scale than European or American ones in the middle of the 20th century. It must also be borne in mind that these visionary developments were led by an elite that was not only intellectually but also economically wealthy. Nevertheless, 25 Cuffe Parade was undoubtedly a space of mutually beneficial and transformative collaborations between locals and exiles.

03Royal Bombay Yacht Club / TIFR/ Apollo Bunder

It may seem surprising that one of the key figures in Bombay’s emerging art scene in the 1940s was a theoretical physicist. A Nobel-prize nominee, Homi Bhabha is widely credited as the architect of India’s nuclear programme. Bhabha, however, was almost as passionate about painting as he was about sub-atomic particles. Besides creating his own works of art, Bhabha was also an important patron of the arts. He was able to marry his interests in science and art through the Tata Institute for Fundamental Research (TIFR), which he founded at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore in 1945 and moved to Bombay the same year. Funding was initially granted by the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust before the national government stepped in to bankroll the project. Unusually, the budget included an allocation for purchasing art.

Homi Bhabha on a stamp, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

Homi Bhabha commemorative envelope and stamp, 1966 (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

Homi Bhabha’s garlanded portrait in the security cabin at the entrance to TIFR, 2018 (© Rachel Lee).

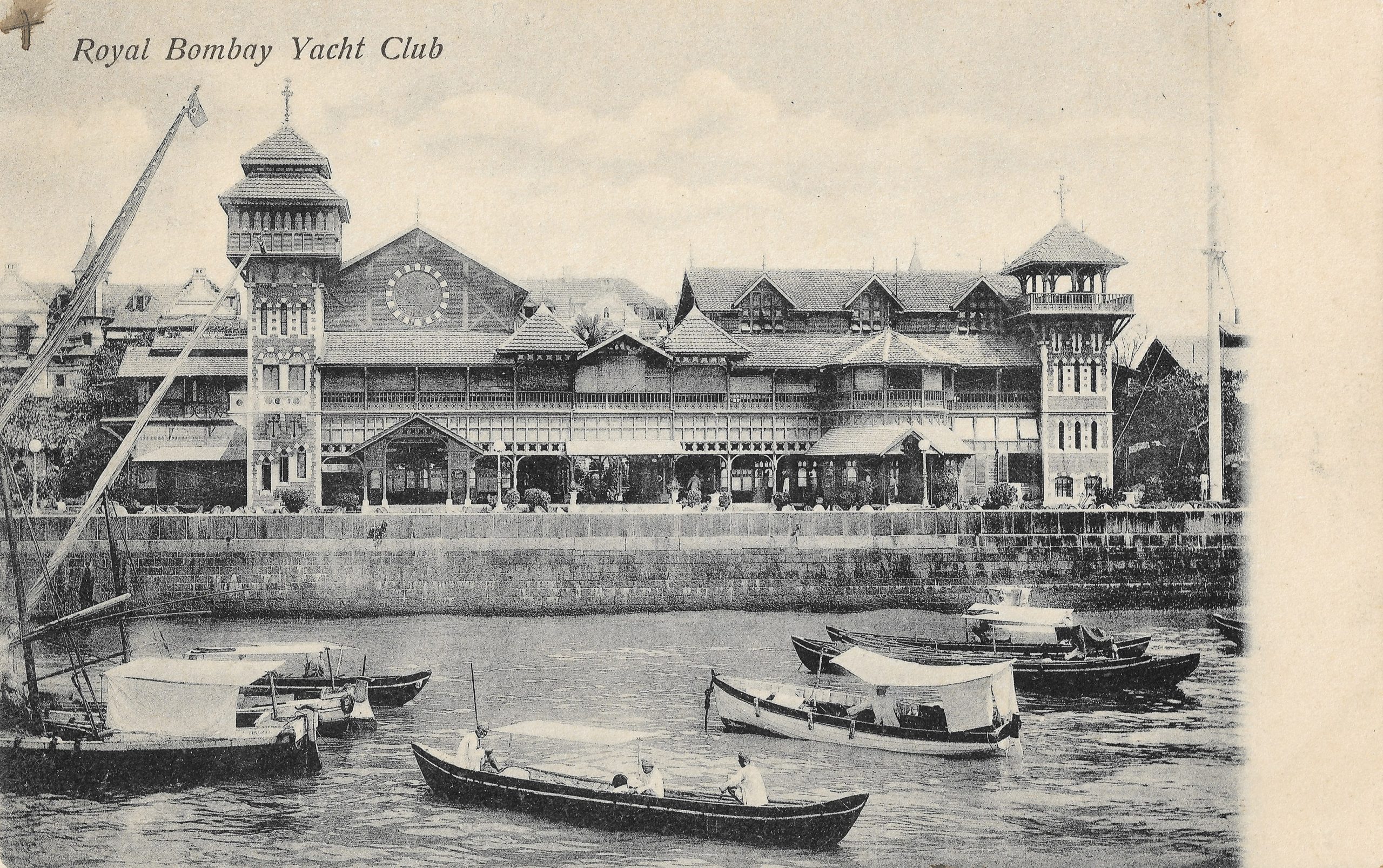

In 1949, TIFR relocated to what had been the premises of the Royal Bombay Yacht Club. Constructed in 1881, the Yacht Club was a prominent social space in the colonial city, with a racist Europeans-only policy. Its transformation into a cutting-edge Indian scientific institute just two years after Indian independence shows the determination of the new government to divest from imperial vestiges and to invest in nation-building projects. It probably also attests to prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s personal friendship with Homi Bhabha.

Postcard “Royal Bombay Yacht Club”, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

Louis Bromfield discusses why the American businessman Mr Wainwright does not want to visit the Yacht Club in Night in Bombay (Bromfield 1946, 121).

In the early 1950s Bhabha began collecting artworks for the TIFR collection. In about a decade, and supported substantially by the advice of Pipsy (Pheroza) Wadia, Bhabha amassed one of the most significant collections of Indian modern art worldwide. The vast majority of works purchased were contemporary pieces by practising artists, including K.H. Ara, V.S. Gaitonde, H.A. Gade, M.F. Husain, Krishna Khanna and Shivax Chavda as well as the women artists Prabha Agge, Pilloo Pochkhanawala and Jyoti Shah.

Sketch of Pipsy Wadia by Bhabha, 1943 (© TIFR, Google Arts & Culture).

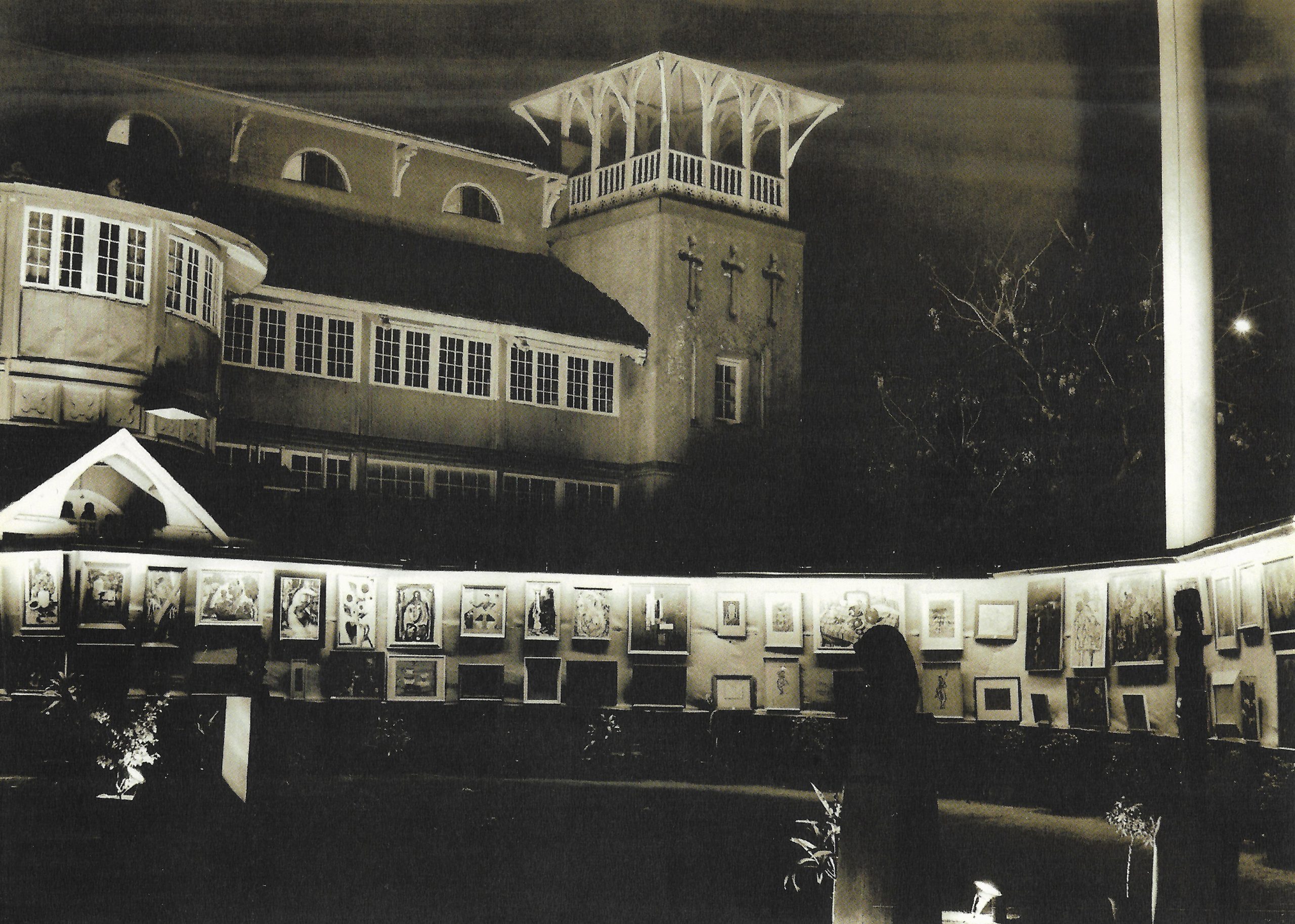

Art exhibition held at TIFR in the Royal Bombay Yacht Club, late 1950s (Chatterjee 2010, 22).

According to TIFR’s list of works, the third piece purchased for the collection was a decorative panel by Walter Langhammer in 1952. It cost 375 INR, equivalent to 1785 USD at the time and around 17,545 USD today. A landscape by Langhammer was purchased in 1955, and Langhammer’s portrait of Rudi von Leyden, titled The Critic from 1943 also found its way into the collection. Von Leyden was a close personal friend of Bhabha’s and he was involved in other aspects of TIFR’s artistic development, including as an adviser.

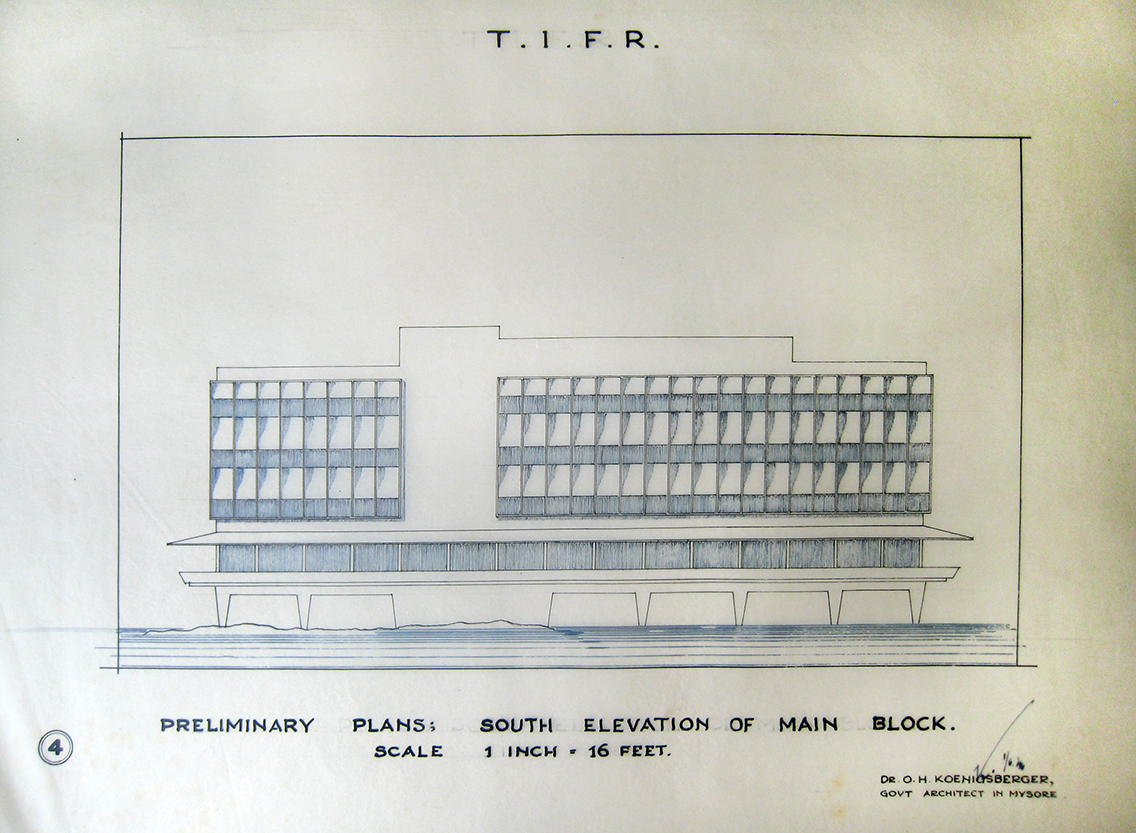

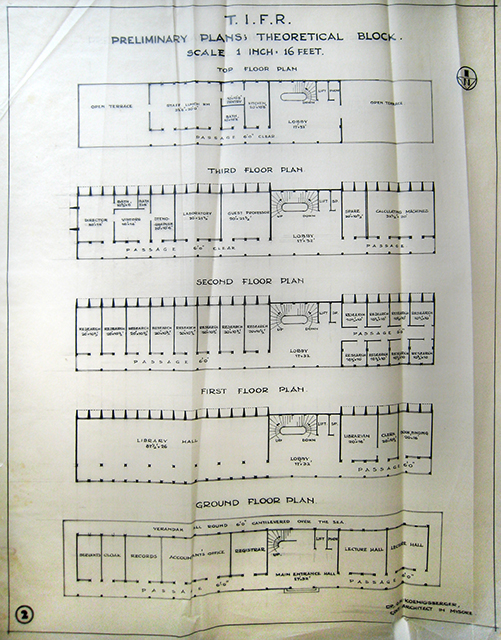

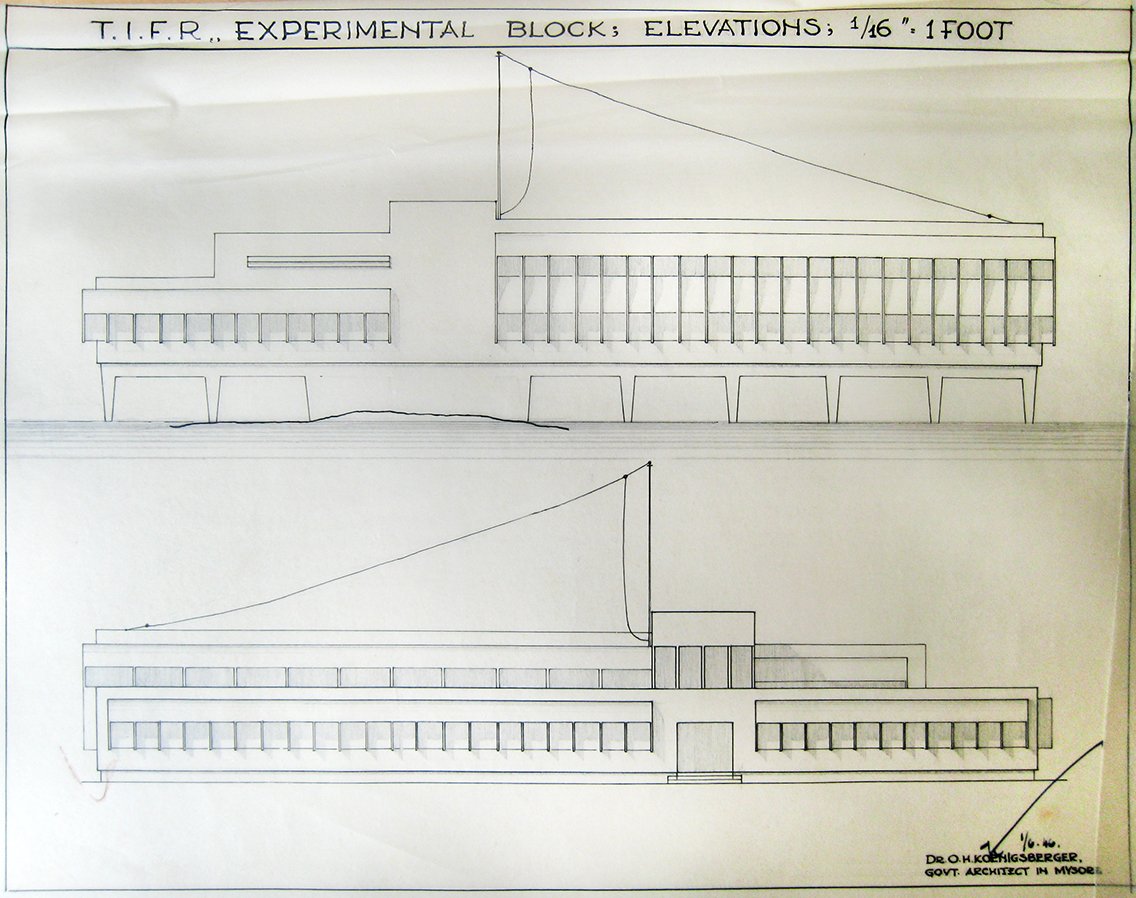

The Royal Bombay Yacht Club was intended to provide a temporary home for the Institute until a purpose-built building was constructed elsewhere in the city. Initial designs for the new building were prepared by the Bombay-based architecture firm Master, Sathe and Bhuta as well as by the exiled architect and urban planner Otto Koenigsberger. Koenigsberger, who at the time was the Chief Architect and Town Planner of Mysore State in South India, was also a close friend of Bhabha and spent several weeks in Bombay, working on his designs.

Elevation of the main block of the new TIFR building by Otto Koenigsberger, 1946 (Otto Koenigsberger’s Private Collection).

Plans of the theoretical block of the new TIFR building by Otto Koenigsberger, 1946 (Otto Koenigsberger’s Private Collection).

Elevations of the theoretical block of the new TIFR building by Otto Koenigsberger, 1946 (Otto Koenigsberger’s Private Collection).

Letter from Homi Bhabha to Otto Koenigsberger, 28 May 1947 (Jewish Museum Berlin Archives).

It was however the Chicago firm of Holabird and Root that eventually developed the plans, with detailed design work being prepared by Achyut Kanvinde and Master, Sathe and Bhuta. TIFR moved into the new premises in Colaba in 1962.

The gardens of the TIFR building, 2018 (© Rachel Lee).

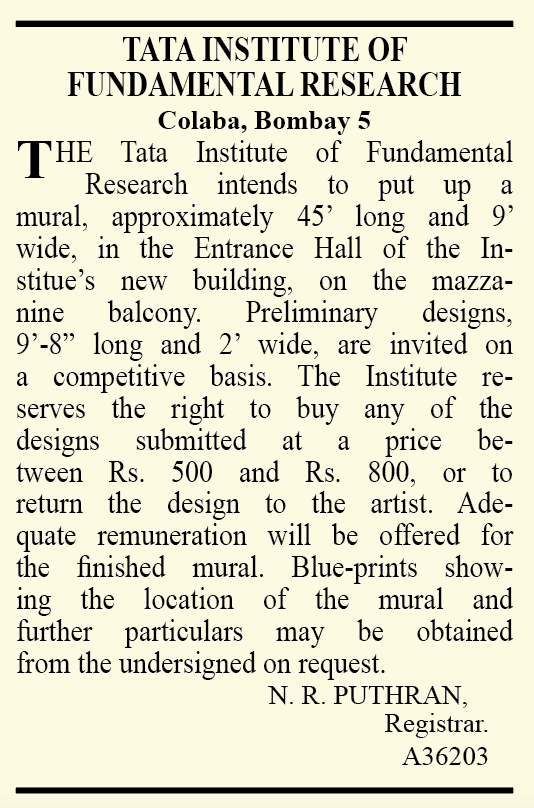

As the building work progressed, Bhabha decided to hold a competition for the design for a mural in the entrance foyer. Of the twelve artists invited to take part in the competition, nine were already represented in the TIFR collection. Judged by Bhabha, Wadia, von Leyden, the art historian Karl Khandalavala and K. Chandrasekharan of TIFR, M.F. Husain was chosen to complete the mural, creating a piece titled Bharat Bhagya Vidhata that, along with the many other artworks in the collection, continues to enrich the Institute today.

Newspaper announcement of the mural competition (The Times of India,12 October 1962, 14).

Bharat Bhagya Vidhata by M.F. Husain, 1963 (© TIFR, Google Arts & Culture).

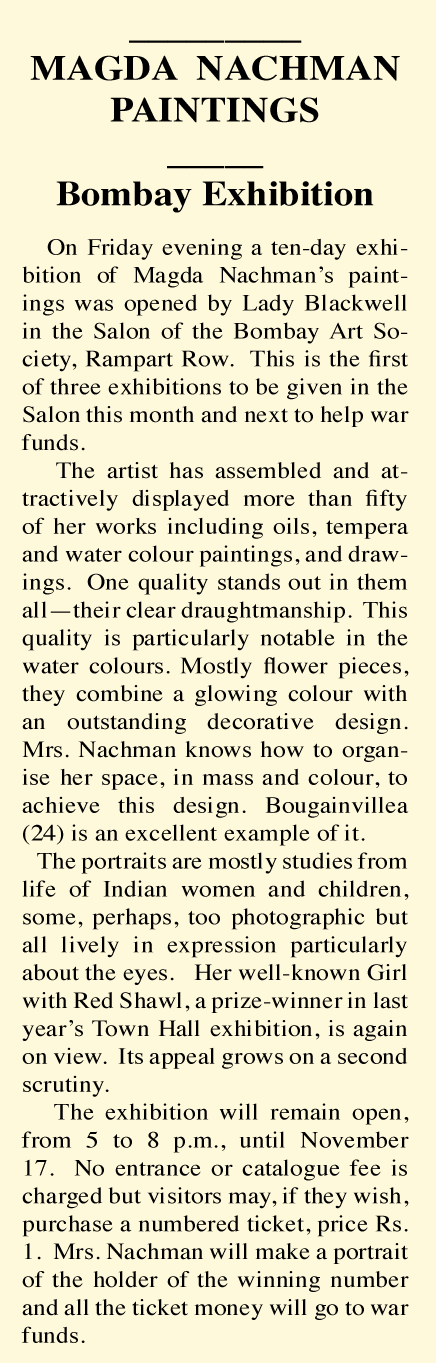

04Bombay Art Society Salon/ 6 Rampart Row

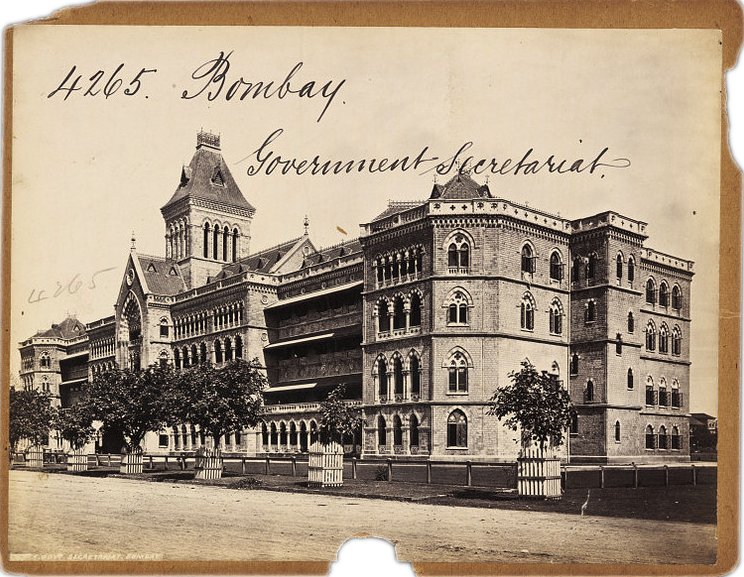

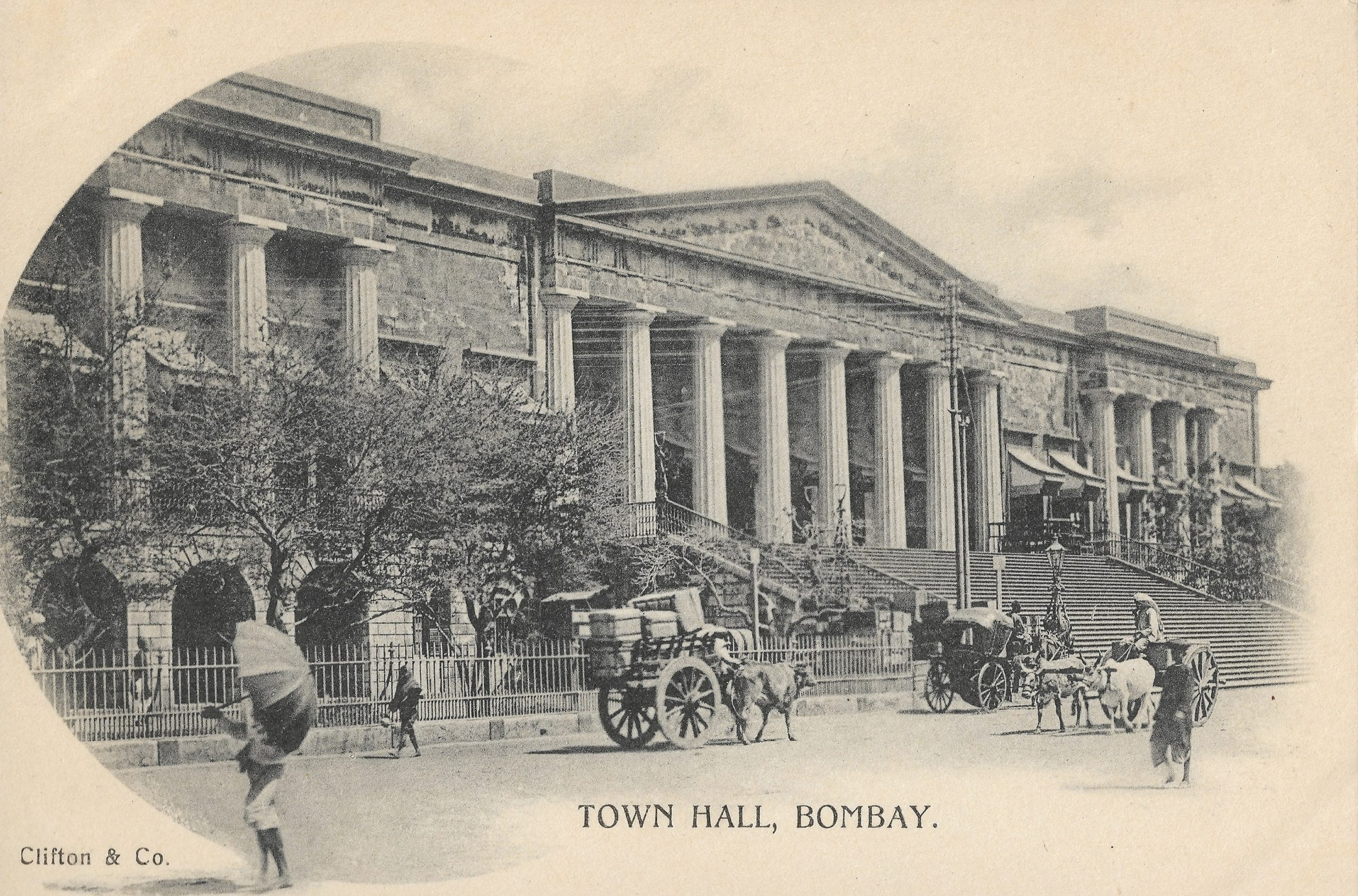

Until the Bombay Art Society established a salon on Rampart Row in 1939, it didn’t have a fixed exhibition space. For over fifty years, the colonial institution, which was founded in 1888, had limited its public activities to an annual exhibition, held at different institutional locations: the Secretariat, the Bombay University Convocation Hall, the J.J. School of Arts, the Cowasji Jehangir Hall, and, more frequently, the Town Hall.

Secretariat building, n.d. (www.oldindianphotos.in).

Bombay University Convocation Hall, n.d. (www.oldindianphotos.in).

Cowasji Jehangir Hall, n.d. (Alamy).

J.J. School of Arts, 1924 (PAP, Public Domain, via architexturez.net).

Town Hall, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

These yearly exhibitions were the main event in Bombay’s art calendar, attracting large numbers of visitors and showcasing mostly academic works by a variety of artists – from ambitious hobbyists to purposeful professionals. Prizes were awarded in a range of categories, including oil painting, needlework, sculpture, photography and, in its early years, “native gentlemen”. By the mid-1930s, the Bombay Art Society’s approach to fulfilling its aim of “encouraging art, especially amongst amateurs, and of educating the native public of its merits” (Muller 1910, 1) was becoming increasingly anachronistic. In Bombay’s artistic community there was a growing desire for a less paternalistic format.

Cover of the Bombay Art Society Journal, 1910 (© Bombay Art Society)

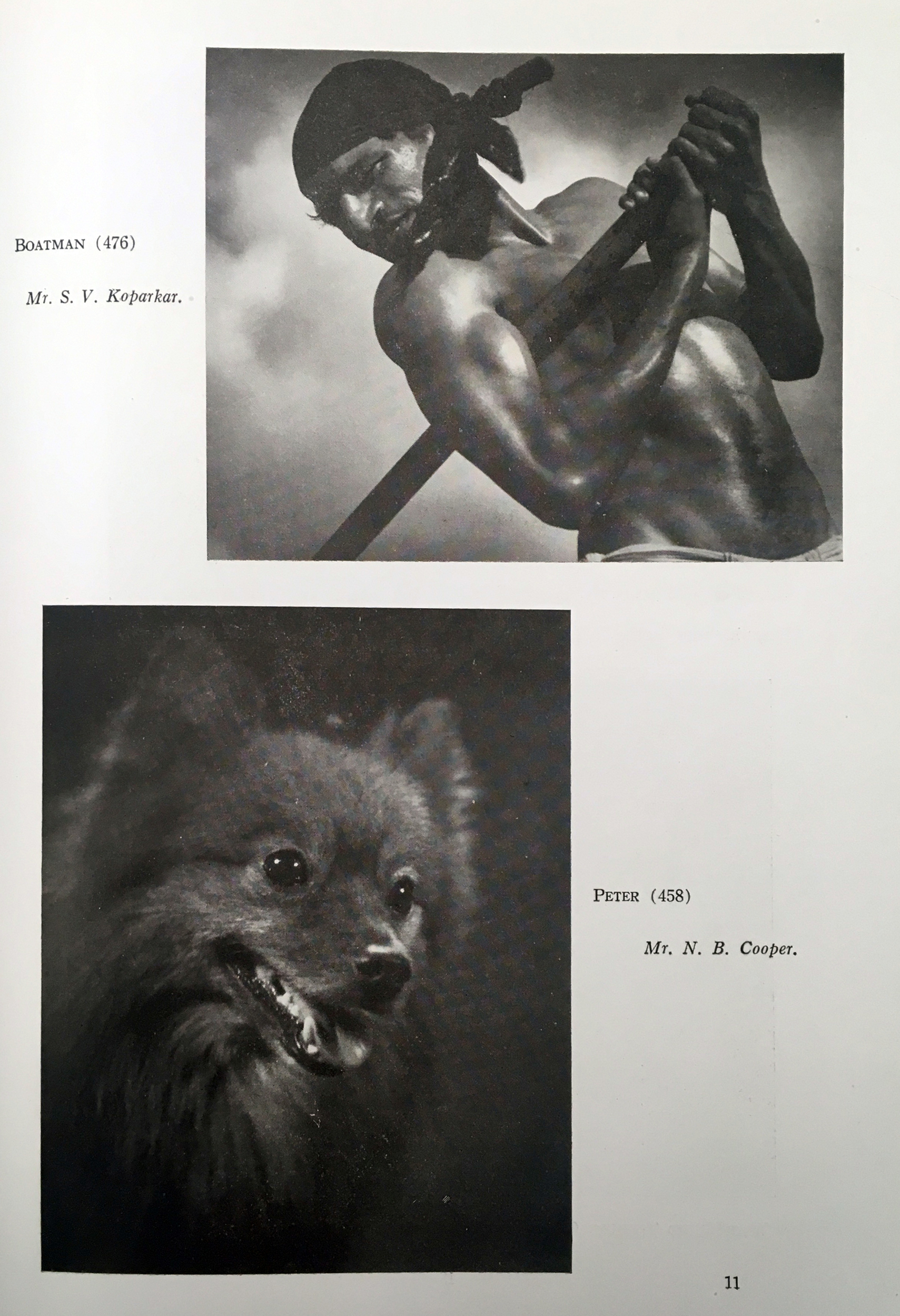

“Boatman” and “Peter”; exhibits from the 1909 annual exhibition (Bombay Art Society 1910, 11).

Announcement in The Times of India, 11 February 1895, 2.

Advertisement in The Times of India, 22 February 1907, 6.

Advertisement in The Times of India, 10 January 1923, 11.

F.N. Souza remembers the Bombay Art Society’s annual shows (Patriot Magazine, 1984, 11).

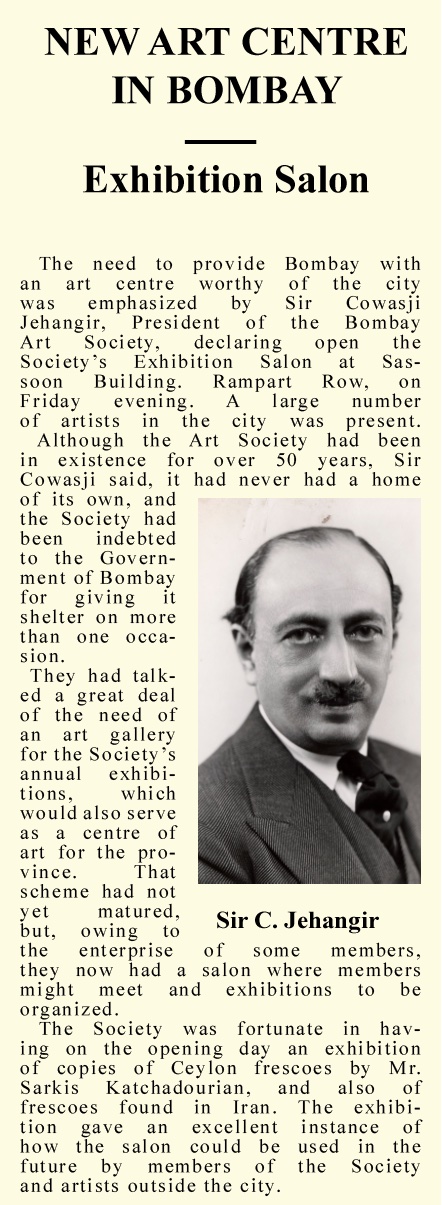

Several exiled artists helped foment the desired change from within the Society. As well as taking part in the annual exhibitions and even winning prestigious prizes, Walter Langhammer took over the role of chairman in 1939 and Rudi von Leyden became a board member. Later Langhammer’s wife Käthe joined the board, too. Together with the other board members and with the financial support of the Society’s president, Sir Cowasji Jehangir, the Bombay Art Society Salon was created.

The Salon provided an intimate, social space that encouraged its visitors to engage with art rather than simply consuming it. Its programme – which was on hold between 1940 and 1945 when the premises were requisitioned in connection with the Second World War – offered lectures, discussions, demonstrations, film screenings and temporary exhibitions. Individual and group shows featured local artists including the Progressive Artists’ Group as well as artists from beyond Bombay, including George Keyt from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Jamini Roy from Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Sam Tata from Shanghai.

New Art Centre in Bombay ( The Times of India, 18 May 1940, 2).

Review of Souza’s exhibition (The Times of India, 20 January 1948, 4).

Review of Devi Das’ exhibition (The Times of India, 21 August 1949, 3).

The Salon was also home to the Artists’ Aid Fund exhibitions, which were initiated by Rudi von Leyden and his brother Albrecht in 1948. Artists contributed paintings for sale with the proceeds going to local artists who found themselves in financial difficulties as well as towards sponsoring scholarships abroad.

Much more than the annual exhibitions, the Bombay Art Society Salon empowered a local community centred around art. Its presence also impacted its surroundings: A few doors down Rampart Row towards Kala Ghoda, the Chetana Culture Centre opened in 1946. The Salon, which was renamed Artists’ Centre, was forced to vacate its long-time home in the Ador House (formerly Radia House and Sassoon Building) in late 2019.

“Artists’ Aid” (The Times of India, 23 August 1950, 6).

“Big Choice Before Bargain Hunters” (The Times of India, 27 August 1950, 2).

Ador House, 2017 (https://mumbai-eyed.blogspot.com/2017/02/ador-house.html).

05Soona Mahal/ 143 Marine Drive

The Soona Mahal has been presiding over the junction where Veer Nariman Road (formerly Churchgate Street) meets Marine Drive since 1937. Designed by the architects Suvernapatki and Vora with supervision from G.B. Mhatre, the building was commissioned by the Parsi liquor trader Kawasji Fakirji Sidhwa and named after his wife, Soona. From its corner site, it enjoys sublime views of the Arabian Sea and looks down a chain of similar Art Deco apartment buildings, which elegantly follows the arc of Marine Drive towards Chowpatty Beach. Built on land claimed from the sea during the early 20th century, Marine Drive represented the epitome of modern living in 1940s Bombay, and its waterfront promenade quickly became a magnet for sunset strolls and weekend outings with friends, families or lovers.

View of Marine Drive taken from the Soona Mahal, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

Soona Mahal, 2018 (© Rachel Lee).

This certainly wasn’t the worst place for the exiled writer, critic and publisher Willy Haas to begin accustoming himself to his new urban environment. Willy Haas, who fled Berlin via Prague, moved into the Soona Mahal in June 1939. He lived in Lesser’s Boarding House, one of several short-term accommodation options available in the building at the time.

Classified advertisement for Lesser’s boarding house in the Soona Mahal (The Times of India, 25 October 1939, 2).

Classified advertisement for accommodation in the Soona Mahal (The Times of India, 18 November 1939, 2).

Classified advertisement for accommodation in the Soona Mahal (The Times of India, 27 May 1939, 2).

Lesser’s was run by an exiled Austrian-German-Jewish husband and wife team – Max and Elli Lesser – and provided a first home for many refugees from German-speaking Europe. In one of the more tragic stories of exile in Bombay, Elli Lesser appears to have ended her life by falling from one of the Soona Mahal’s balconies in December 1941, dying on impact with the pavement below.

Report of Elli Lesser’s death (The Times of India, 11 December 1941, 9).

Fatal Fall from Building (The Times of India, 12 December 1941, 3).

Account of Elli Lesser’s death by Hetty Kohn in her letter to Willy Haas, as reproduced in Franz 2015, 168f.

The “mental torments” of migration that Elli Lesser likely endured are addressed in Willy Haas’s book Germans beyond Germany from 1942. The book is both a harsh critique of German culture and an anthology of writings by German authors who wrote from positions of marginality, including exile. Possibly avoiding the word “German” in the acknowledgements, Haas thanks all the “Czechoslovakian and Jewish gentlemen” who had lent him books they had carried with them to India that helped him collate the anthology. Accessing German publications was clearly a challenge in Bombay and depended on the support of exilic networks.

The Soona Mahal was conveniently located for Haas’s daily commute to Dadar, where he worked at Bhavnani Studios: the local train left from Churchgate Station, which was a short walk from his lodgings. Haas scripted several successful films including Kanchan, Jhooti Sharam (Naked Truth, an adaptation of Ibsen’s Ghosts), and Prem Nagar (An Indian Village Story).

Haas’s description of getting to work in the monsoon (Haas 1960, 227f.).

The Soona Mahal was a landmark in Bombay’s social scene. Its ground floor premises housed a variety of cafés including the Parisian Dairy, where locals and exiles met over frothy milkshakes and cake. Haas recalled anti-war protesters congregating there after a demonstration, and Amrit Gangar described it as an “adda,” a meeting place, for European and local intellectuals and artists (Gangar 2013, 26). As Bombay’s jazz scene flourished during the 1940s and ’50s, Churchgate Street became its main stage: Mongini’s, Gaylord’s, Napoli, Bombelli’s, Berry’s, Society, and the Other Room were all popular venues, as was Talk of the Town in the Soona Mahal.

By that time, however, Willy Haas had moved to the foothills of the Himalayas, where he enlisted with the Indian Army and served until the end of World War II, returning to Europe in 1947. Reflecting on India after Gandhi’s assassination, he recognized the profundity of his experiences in exile, “I suddenly knew that I would never understand this country; not the country, and not its people. But I could love it. And I still love it today. And maybe there is a kind of higher understanding in love itself, which, however, cannot be expressed in words” (Haas 1960, 267).

06Queen’s Mansion/ Prescott Road (Today: Ghanshyam Talwatkar Marg)

Queen’s Mansion is located in a relatively quiet quarter of Bombay’s historical centre, sandwiched between the commerce of Dadabhai Naoroji (D.N.) Road (formerly Hornby Road) and the green triangle of Azad Maidan (formerly Bombay Gymkhana Maidan).

Queen’s Mansion, 2018 (© Rachel Lee).

Queen’s Mansion, 2018 (© Rachel Lee).

Queen’s Mansion, 2018 (© Rachel Lee).

Although Queen’s Mansion was built in 1902 as large flats, its floors were gradually taken over by commercial, cultural, and occasionally military uses. During World War II, the British military Field Intelligence Unit was run from the building. From the early 1940s, the second floor of the building was home to the exiled expressionist Viennese dancer, choreographer and teacher Hilde Holger.

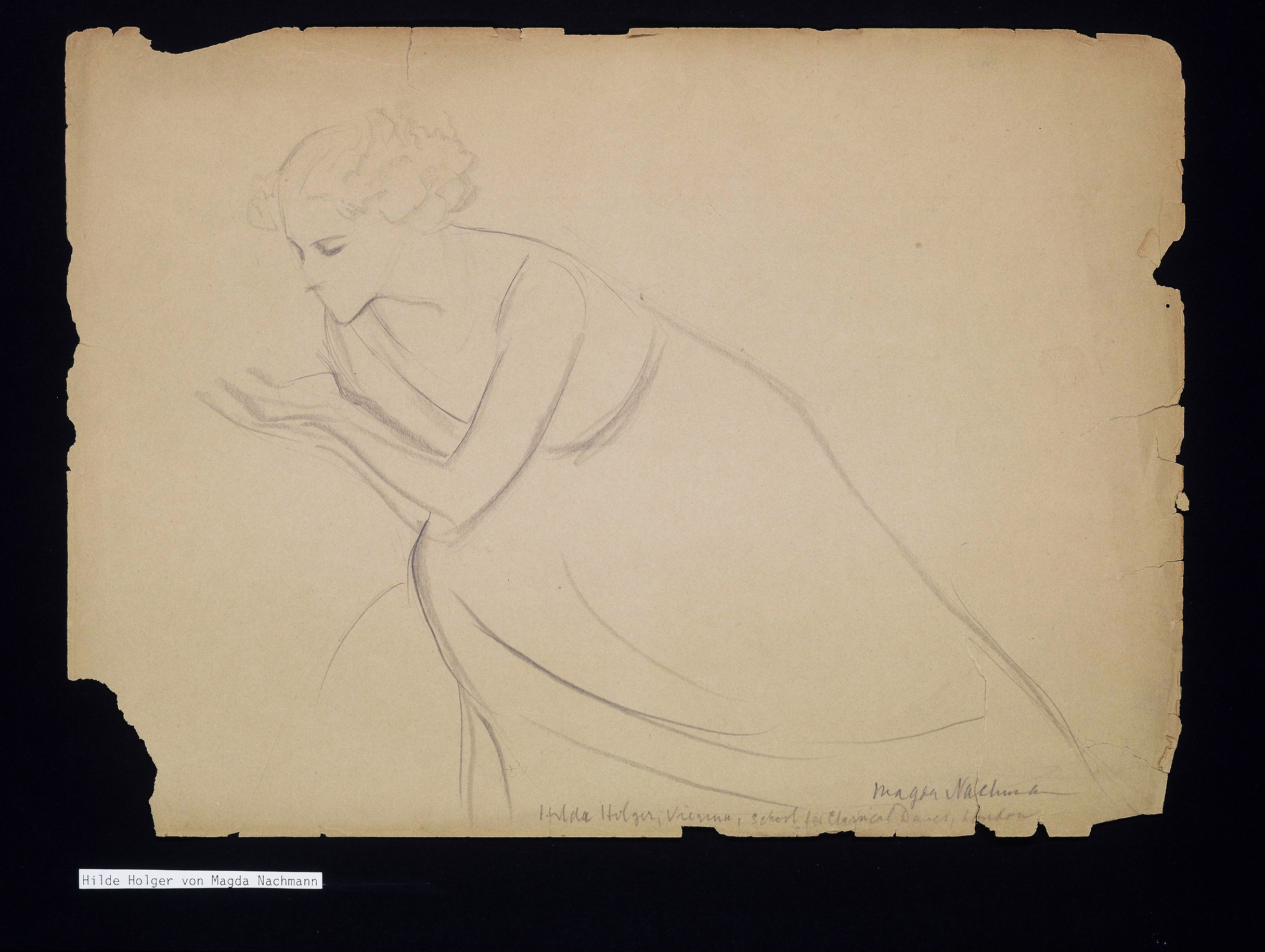

Drawing of Hilde Holger by Magda Nachman, 1940s (Hilde Holger Archive © 2001 Primavera Boman-Behram).

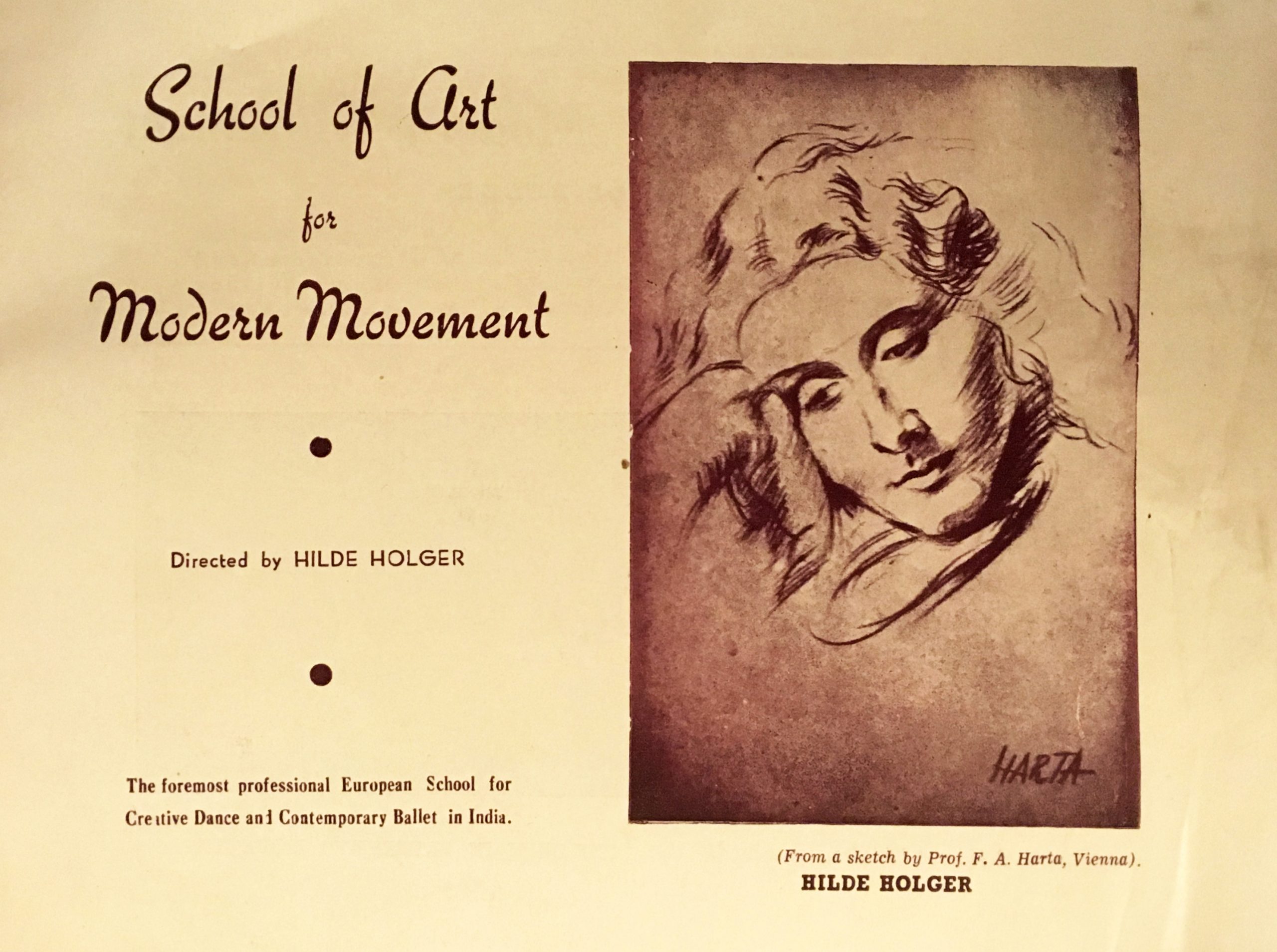

It also accommodated her dance school, The School of Art for Modern Movement, which opened in October 1941 and closed when she left India in 1948. According to her own brochure, Holger’s school was “the foremost professional European School for Creative Dance and Contemporary Ballet in India”. Holger struggled throughout her time in Bombay to establish a sustained interest in European forms of dance. Her school attracted students mainly from Parsi and Anglo-Indian communities, with smaller numbers from Chinese and Hindu backgrounds.

The cover of Holger’s brochure for her dance school in Bombay, 1940s (Hilde Holger Archive © 2001 Primavera Boman-Behram).

A dance class in the Queen’s Mansion studio space with Holger’s daughter Primavera watching from the piano stool, around 1948. (Hilde Holger Archive © 2001 Primavera Boman-Behram).

Students performing the Orchid with Hilde Holger in the centre, 1940s (Hilde Holger Archive © 2001 Primavera Boman-Behram).

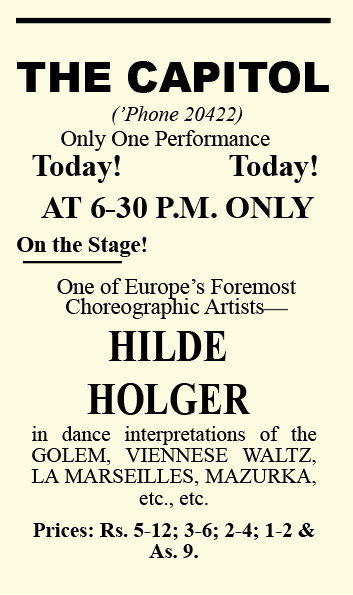

Holger’s own career as a dancer did not flourish in Bombay, and the reviews of her performances were mixed. Her expressionist approach to dancing did not captivate Bombayites in the way it had audiences in central Europe in the 1920s and ‘30s. Her dance school in Queen’s Mansion was therefore her main source of professional expression and fulfilment.

Classified advertisement for Holger’s performance at the Capitol (The Times of India, 1 December 1939, p. 3).

Review of Holger’s performance (The Times of India, 2 December 1939, p. 10).

Review of Holger’s performance (The Times of India, 1 December 1948, 8).

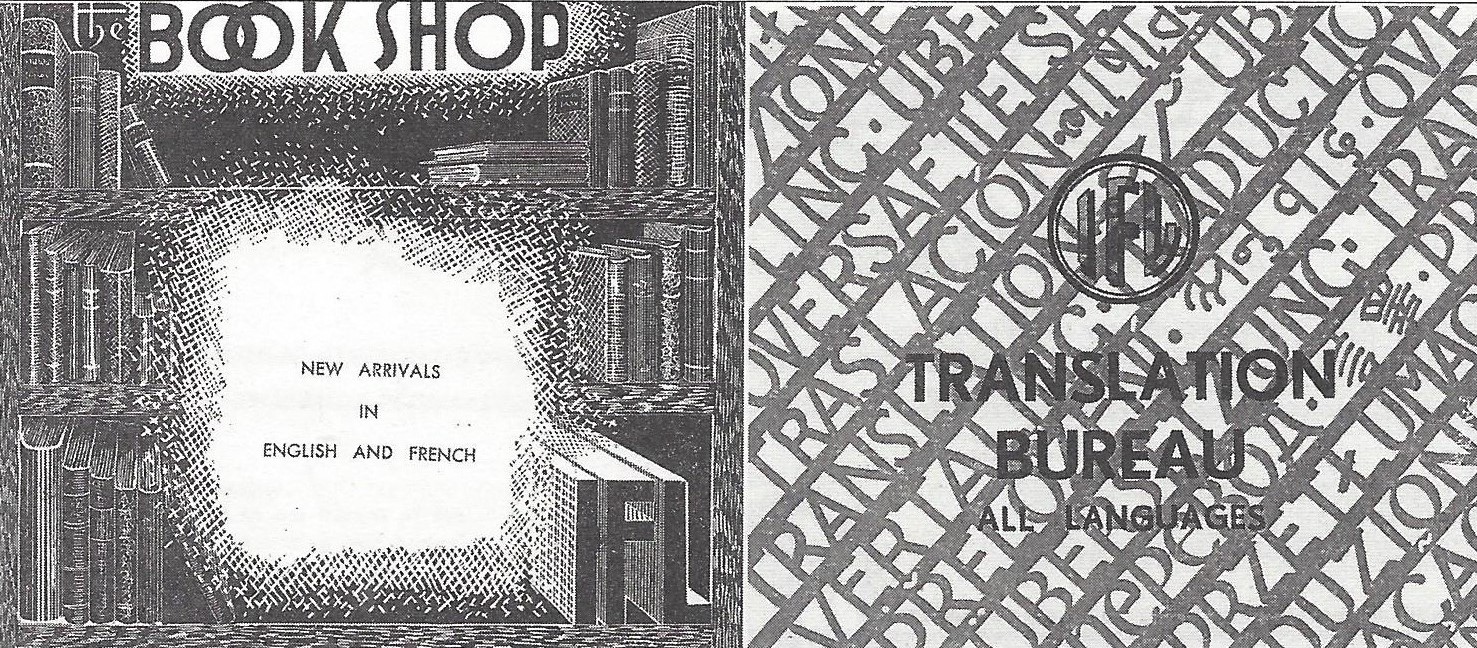

She and her troupe of young dancers would occasionally present their work in public. As the space in Queen’s Mansion was too small to stage performances, they used auditoriums in nearby cinemas, theatres and schools. However, in preparation for the performances, her school was where she developed the costumes and sets, often in collaboration with local musicians and artists, as well as with artists from the exile community. The costumes and sets of the Three Enchanting Ballets, performed at the Capitol in 1943, were designed by the local artist Shiavax Chavda and the exiled painter Magda Nachman. The set for a 1948 performance at St. Xavier’s College was designed by the artist S.H. Raza. For Holger, the costumes were a crucial aspect of the performance, inseparable from the movement and part of the physical, artistic manifestation of the choreography. Nachman’s involvement as costume designer was significant, and integral to the realization of Holger’s dance visions.

Magda Nachman’s costume design for Baba Yaga, 1943 (Hilde Holger Archive © 2001 Primavera Boman-Behram).

Magda Nachman’s costumes for Russian Fairytale, 1940s (Hilde Holger Archive © 2001 Primavera Boman-Behram).

Painted stage backdrop, 1940s (Hilde Holger Archive © 2001 Primavera Boman-Behram).

Aside from designing for Holger’s productions, Nachman visited Holger in Queen’s Mansion, making sketches and portraits of Holger, her daughter Primavera and the dance students. In a space of intimacy and productivity, Nachman and Holger were able to cultivate personal and professional relationships that enriched their experiences of exile in Bombay. Holger’s studio and home space doesn’t seem to have functioned as a salon in the way Mulk Raj Anand’s did, and perhaps Holger lived a quieter, more family-centred life with her husband Adi Boman-Behram, whom she married in 1940, and their daughter Primavera, who was born in 1946.

Looking from Queen’s Mansion towards the Menkwa building that housed the Institute for Foreign Languages, 2018 (© Rachel Lee).

When the family left Bombay for London in 1948, Holger’s friend and sometime manager, Charles Petras took over the apartment, which was located very close to his Institute for Foreign Languages… the subject of the next stop.

07Institute for Foreign Languages/ Outram Road (Today: Thakurdas Marg)

“‘Peace on Earth, Good Will to All Men’. For which In Our Small Way We Strive” is the inscription on a 1949 Christmas card from the Institute for Foreign Languages (I.F.L.) signed by its founder Charles Petras. The seasonal greetings convey the higher vision according to which the exile Petras had founded the I.F.L. in 1946. The culturally interested Viennese, whose birth name was Karl Petrasch, travelled to India in the mid-1930s to undertake a journalistic trip. Due to the Nazi takeover, the avowed socialist did not return to continental Europe and was interned as an “enemy alien” in India during the war years. Shortly after his release, however, his “good will” encouraged him to make use of his extraordinary knowledge of some 15 languages.

Letters and Logo of the I.F.L., around 1950 (Hilde Holger Archive © 2001 Primavera Boman-Behram).

What started as an international centre for language courses, soon became a space of encounters between diverse communities and art forms. The series “Ten Minutes Talks” motivated members of the I.F.L. to bring their own countries and cultures closer to others. Further endeavours for spoken and written exchanges included a translation bureau, a news journal titled I.F.L. News, a public library and the I.F.L. bookstore, which opened in 1949 with a specific focus on European literature. Petras’ socialization also becomes visible in the graphic design of the I.F.L. activities. In its reduction of forms and the geometrical pattern, borrowings from Austro-German modernism are evident, while the embedding of the logo in a globe expresses the institute’s cosmopolitan self-perception.

Advertisement of the I.F.L. Bookshop and translation bureau, n.d. (Franz 2015, 263).

The I.F.L. programme also included cultural events: they ranged from theatre performances, literary readings, dance and vocal performances to drawing lessons and art exhibitions. Here, contemporary art from Europe as well as India was shown to the Bombay public. One of the first exhibition Petras organised in February 1950 was an exhibition of 70 self-portraits from the collection of the emigrated clothing manufacturer Siegbert Feldberg and his wife Hildegard from Stettin, which included works by Käthe Kollwitz, Oskar Kokoschka and Artur Segal that had been banned as degenerate in National Socialist Germany. The Indian art magazine Marg highlighted the “stimulating experience to get acquainted with the Central European Art of the inter-war period” (Marg 1950, 59), which might have been unknown to a large part of the Indian public until then.

The I.F.L.’s dense network is also evidenced by exhibitions of emerging Indian artists of the renowned Progressive Artists’ Group. One such exhibition was of the abstract Kashmir paintings of H. A. Gade in 1950, which Rudi von Leyden had organised together with his brother Albrecht, Walter and Käthe Langhammer and Emanuel Schlesinger. Simply framed, tightly hung, modernist landscapes and a few figurative paintings in watercolour and sometimes oil must have been radical for those interested in art in Bombay, given the visual conventions of the time.

Newspaper report of Gade’s Kashmir exhibition in the I.F.L., 1950 (© James von Leyden Archive, Lewes).

Like the gradual viewing of the artworks along the corridors and rooms, the visitors to the I.F.L. became part of a cultural exchange only made possible by artistic migrations. It is no coincidence that Petras chose Bombay for this. The city was already considered an economic hub with an international entertainment scene under the British government. The I.F.L.’s first location was in a four-storey building in the heart of the Fort precinct – the Menkwa Building. Another tenant of the building in 1949 was an overseas trader from Australia, indicating the global exchange within its walls. The Edwardian-style brick building was formerly also known as Carlton House, a name which can still be deciphered today on the entrance sign. Around 1950, the I.F.L. moved to premises closer to Bombay’s arts infrastructure. About a kilometre further south in Kala Ghoda, Petras rented “a splendid modern centre with tube lighting and much larger” (Franz 2015, 259), underscoring the institute’s continued success. Nevertheless, all traces of the I.F.L. seem to disappear after Petras’ unexpected death in 1952.

The Menkwa Building, 2019 (© Rachel Lee).

The Menkwa Building and traces of its former name Carlton House, 2019 (© Gautam Muralidharan).

08The Times of India / Hornby Road (Today: D.N. Road)

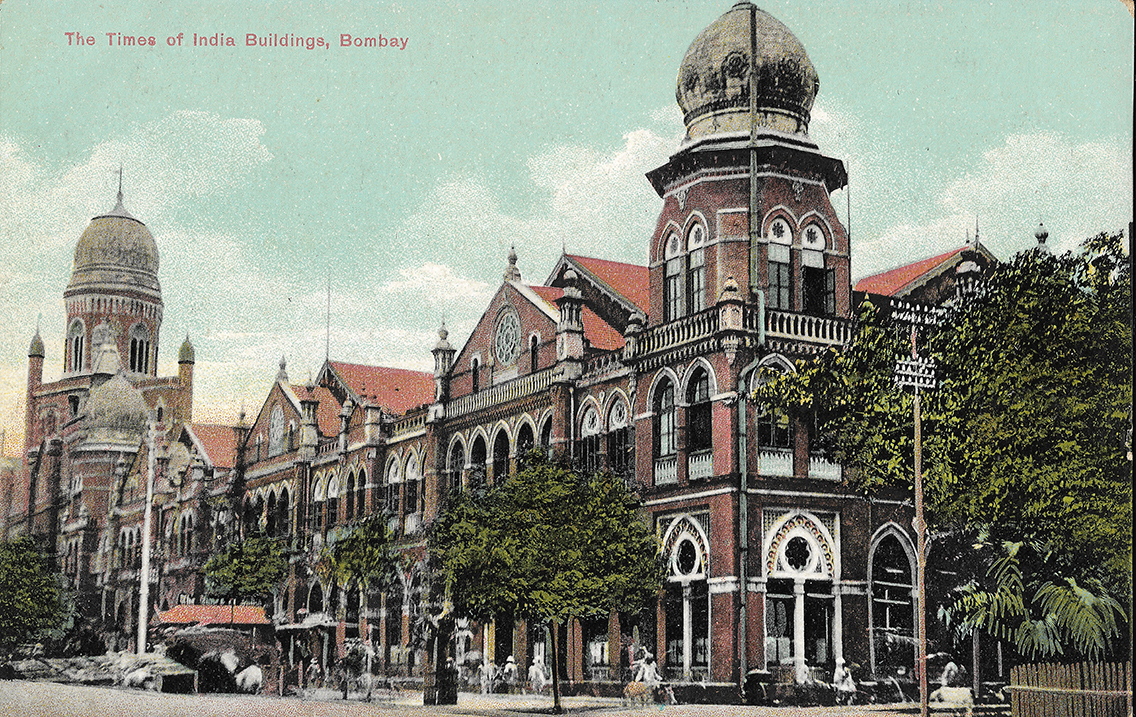

With its corner domes, pointed arches and rose windows, The Times of India building confidently occupies a site next to its similarly styled but more famous neo-Gothic neighbours: the Municipal Corporation Building and Victoria Terminus (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus), both works by F.W. Stevens. Designed by the architect-engineer partnership of David E. Gostling and James Morris, The Times of India building’s foundation stone was laid on the first day of the twentieth century and the finished building was occupied by the press in 1903. Since its founding in 1838 as The Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce, the newspaper has been published in English. It changed its name, perhaps to indicate its national ambitions, in 1861. In the 1930s and 1940s it would have attracted international and colonial readers as well as the English-speaking local elite.

The Times of India building, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

Description of The Times of India from Ben Diqui’s guidebook (Diqui 1927, 20f.).

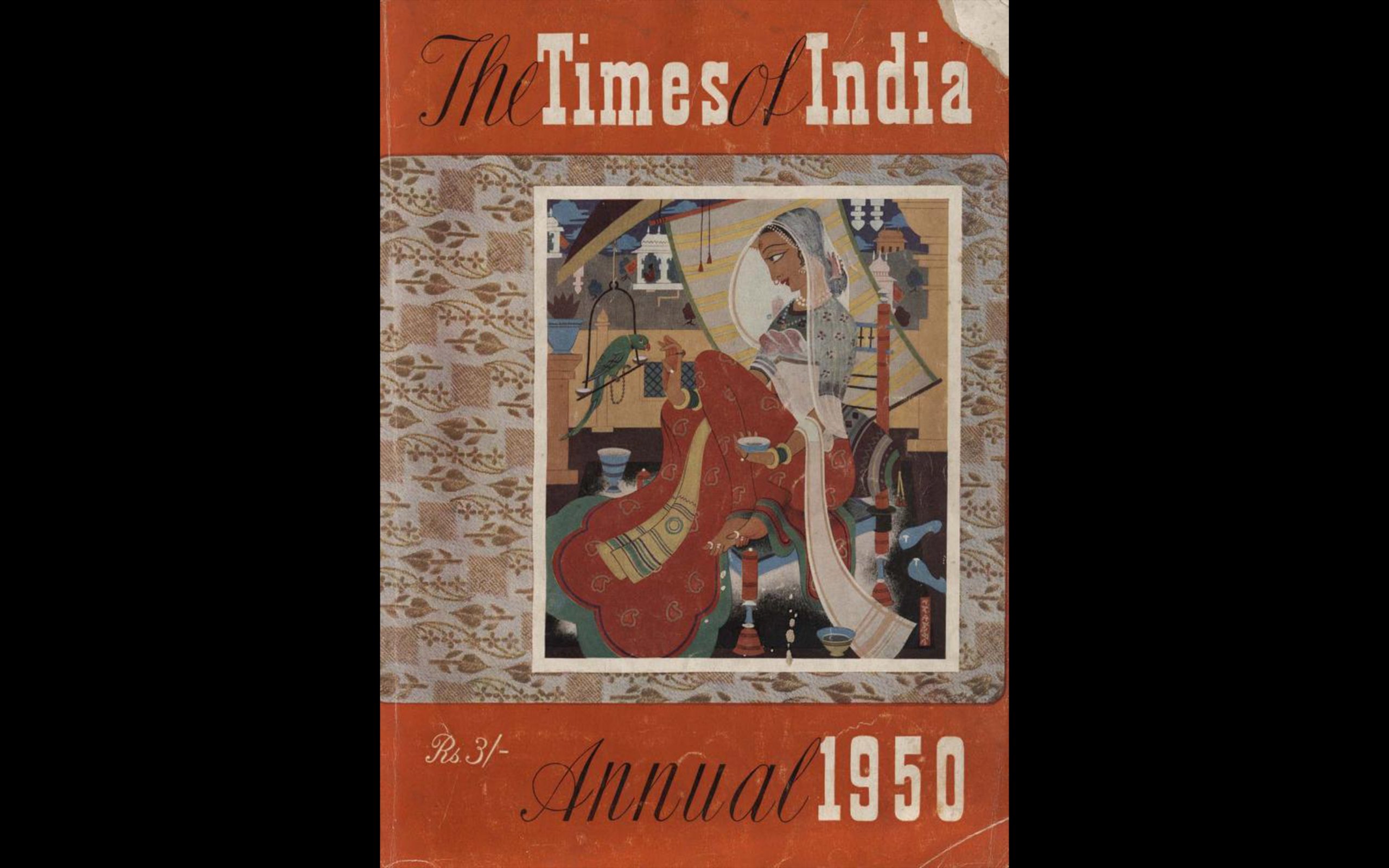

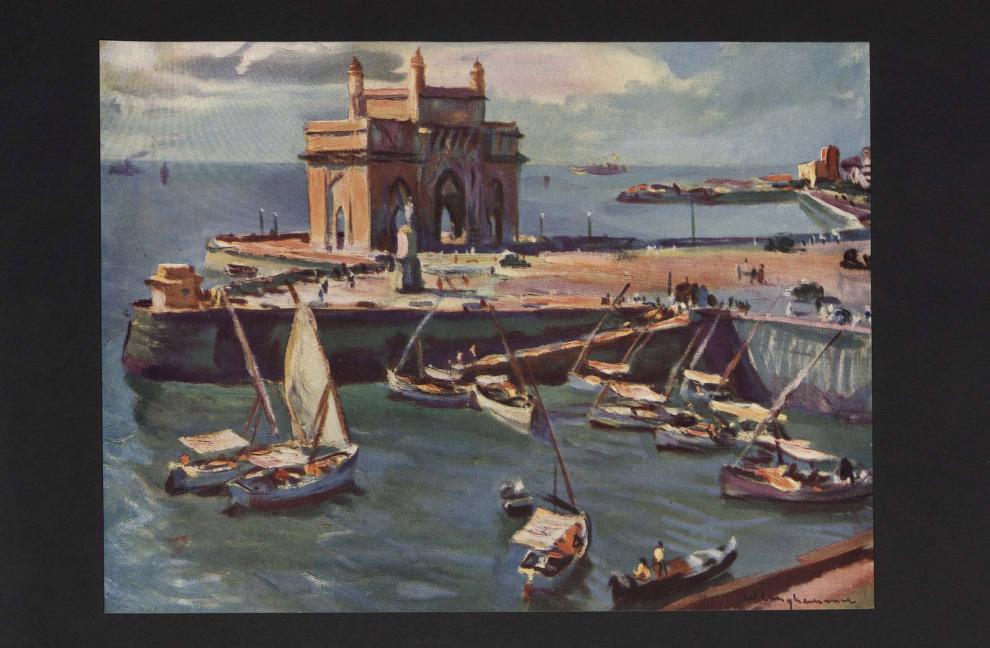

For the exiled artistic community, The Times of India provided information, employment and exposure. Two figures in particular are associated with the newspaper: Walter Langhammer and Rudi von Leyden. For Walter Langhammer and his wife Käthe, the newspaper provided a lifeline after their shared socialist political convictions and her Jewish background put them at risk in Nazi-occupied Austria. An offer of employment as the paper’s art director, which came through a connection Langhammer had made in Vienna, enabled them to escape to Bombay in 1938. As art director, Langhammer’s responsibilities included managing The Times of India Annual – a richly illustrated book that was published yearly in time for Christmas. Often his own paintings were featured.

The Times of India Annual cover 1950 (The Times of India Annual, 1950).

Portrait of Sarojini Naidu by Walter Langhammer (The Times of India Annual, 1950, 36).

Gateway of India by Walter Langhammer (The Times of India Annual, 1950, 55).

The Times of India review of the 1950 Annual (The Times of India, 24 Dec 1949, 8).

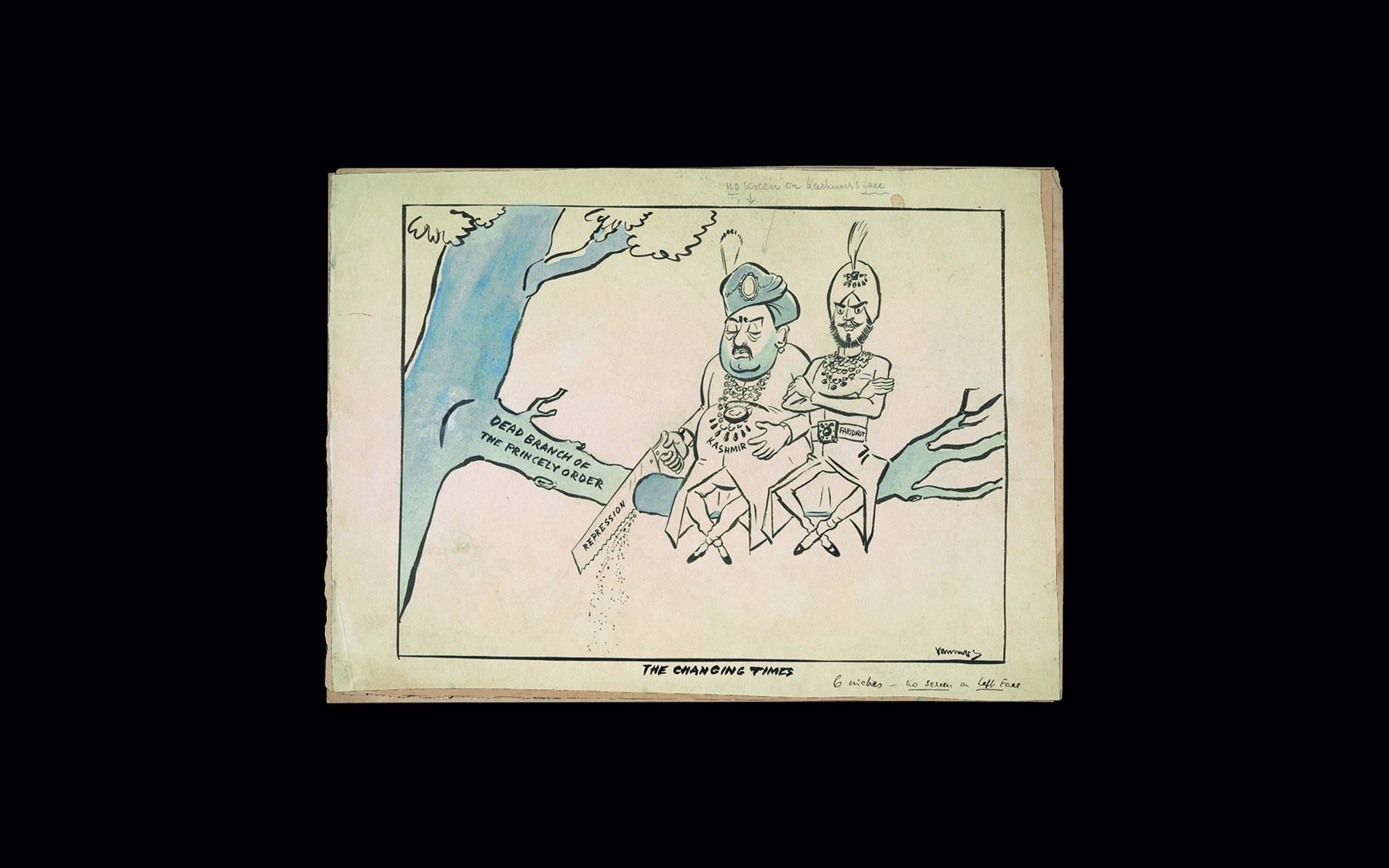

After Rudi von Leyden closed down his Bombay advertising agency in the late 1930s, he took up a position in the advertising department of The Times of India. Soon, he became the newspaper’s art critic, reviewing art exhibitions in the city under his initials RVL. These reviews served to bring the work of contemporary artists to a wider public and he used them as a platform to promote artists that he admired, including some of the Progressives as well as his fellow exiles Magda Nachman and Langhammer. The gallerist Kekoo Gandhy remembers him regularly cycling from an exhibition opening at the Bombay Art Society Salon up Hornby Road to the Times of India building to write up a story for the next day’s issue.

R.V.L. “Mr. F. Newton’s Paintings” (The Times of India, 20 July 1946, 5)

R.V.L. “Wide Range of Paintings” (The Times of India, 18 January 1947, 12)

R.V.L. “Art Exhibition in Bombay” (The Times of India, 12 February 1948, 3)

R.V.L. “Testimonies of Life” (The Times of India, 18 February 1948, 8)

R.V.L. “Bombay Exhibition of Photographs” (The Times of India, 15 September 1948, 5)

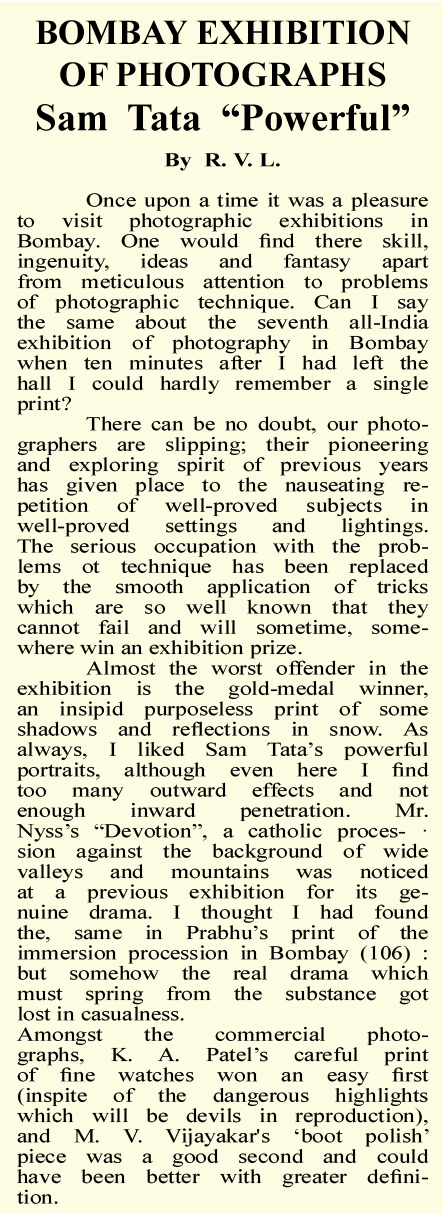

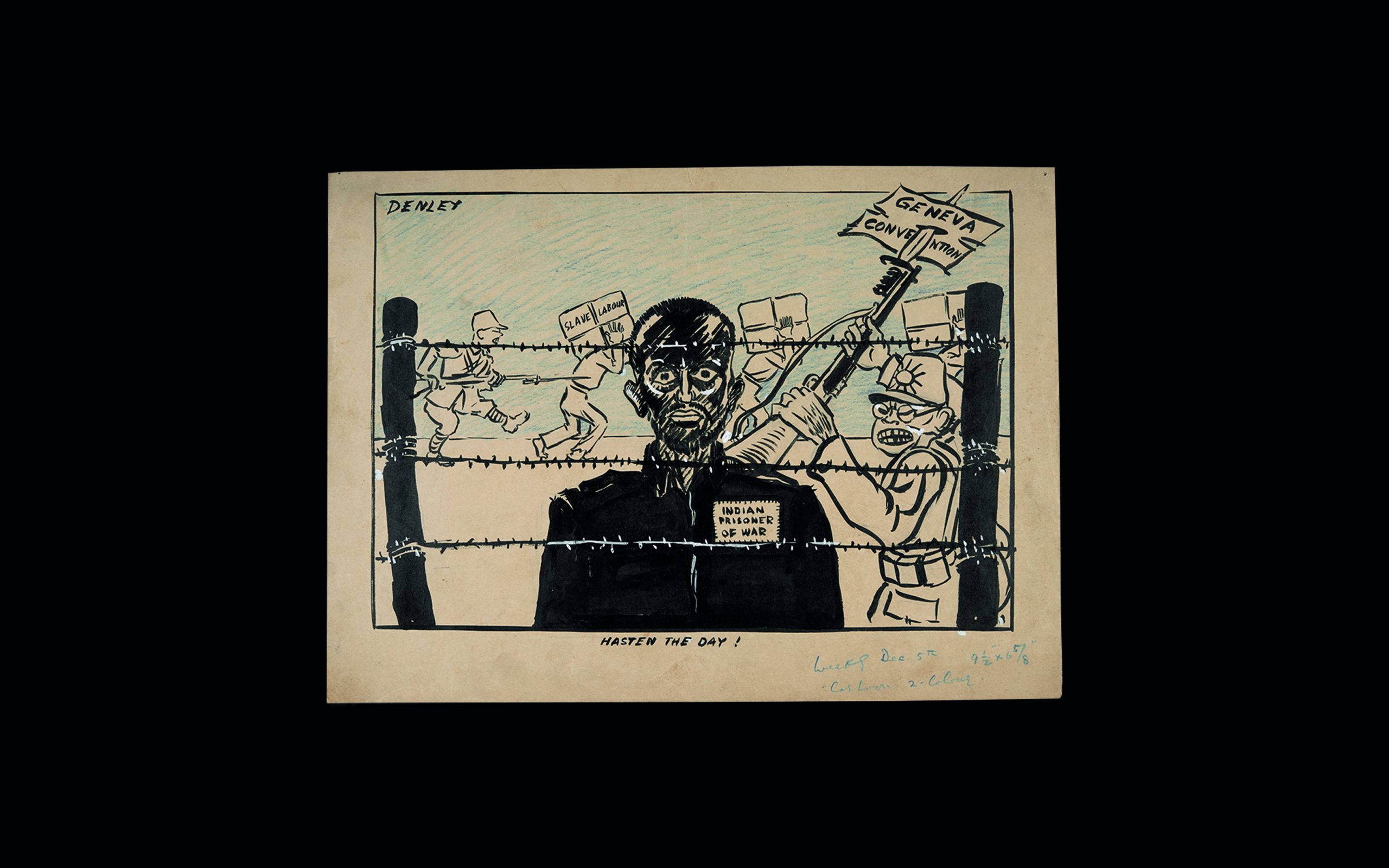

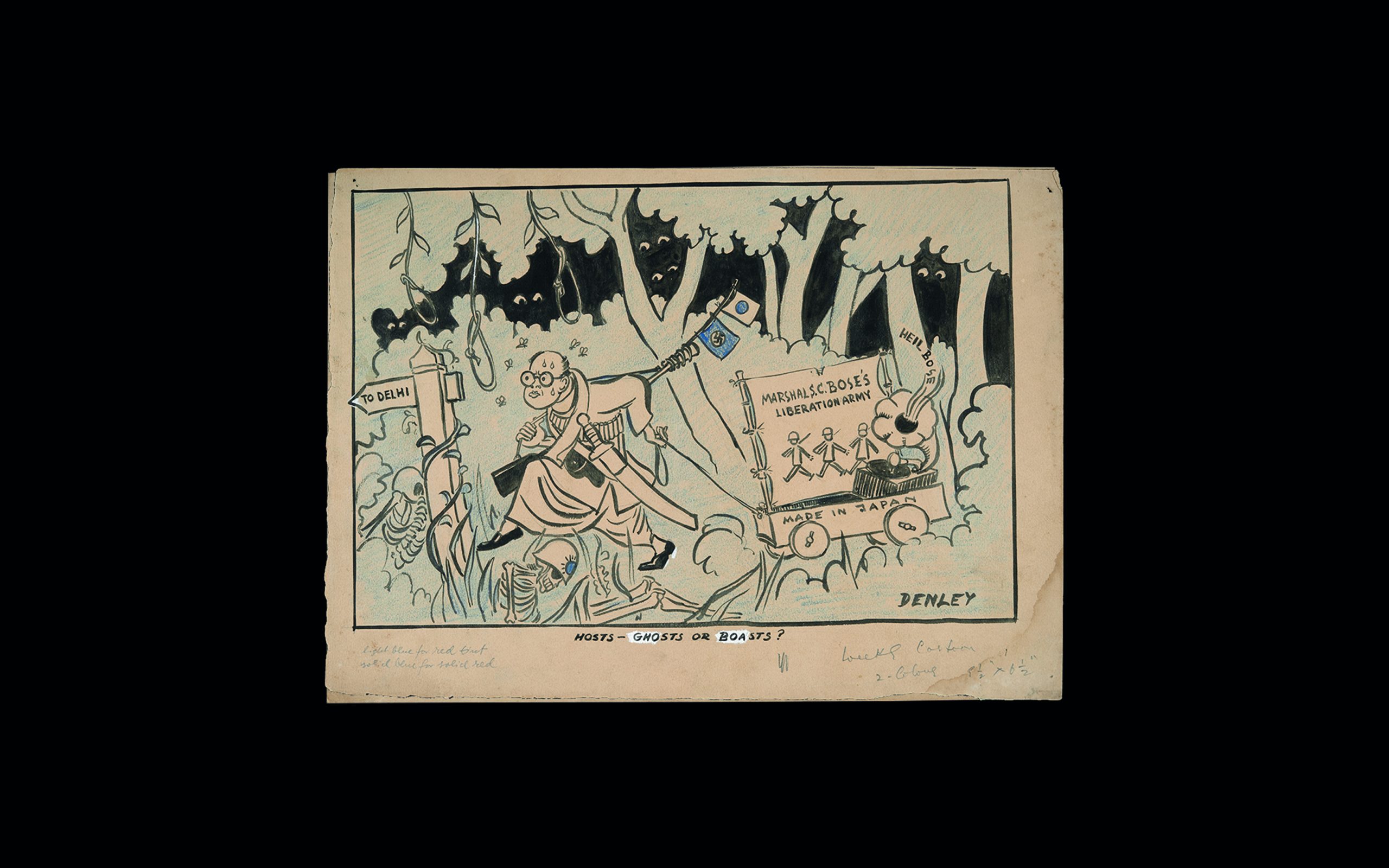

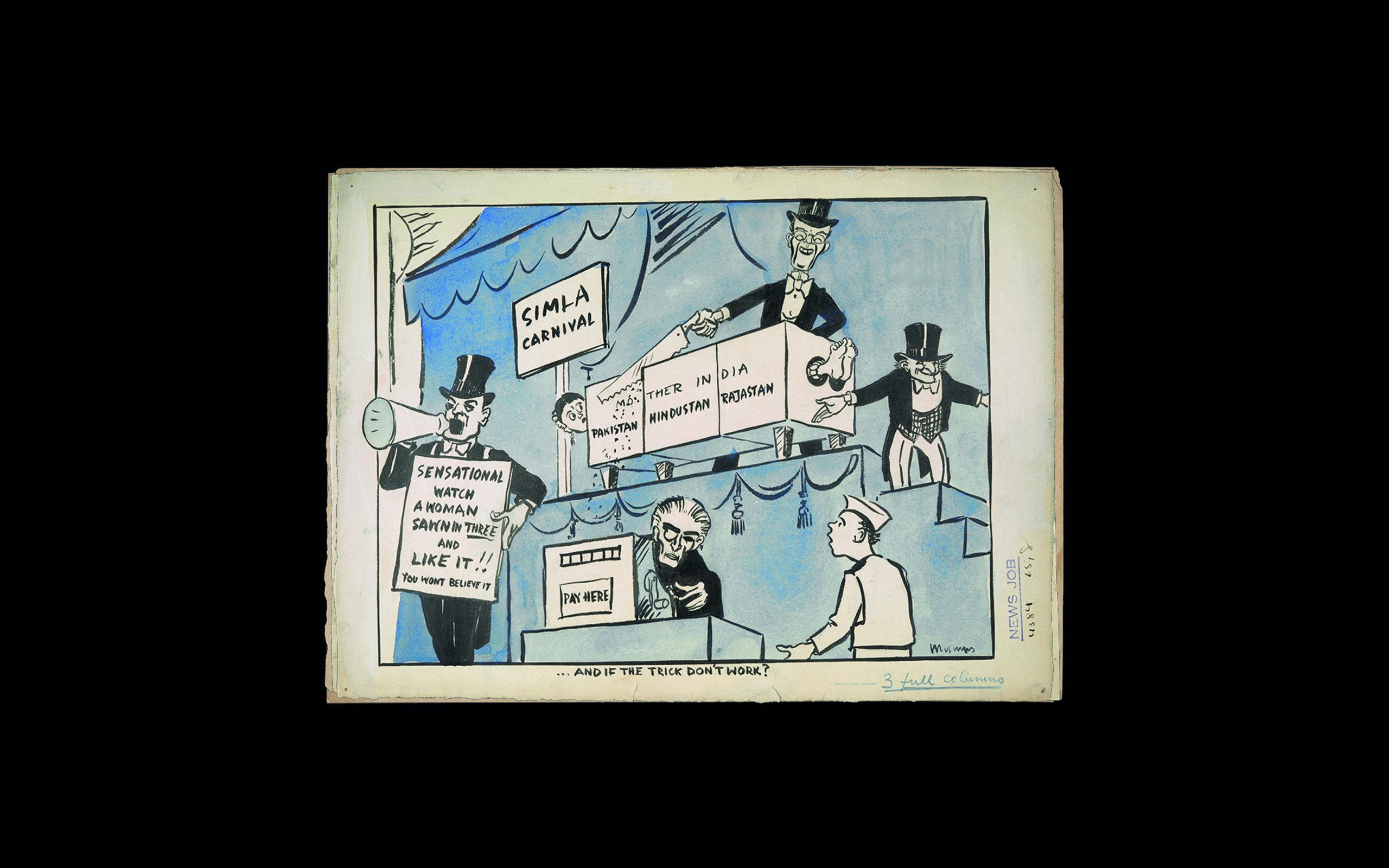

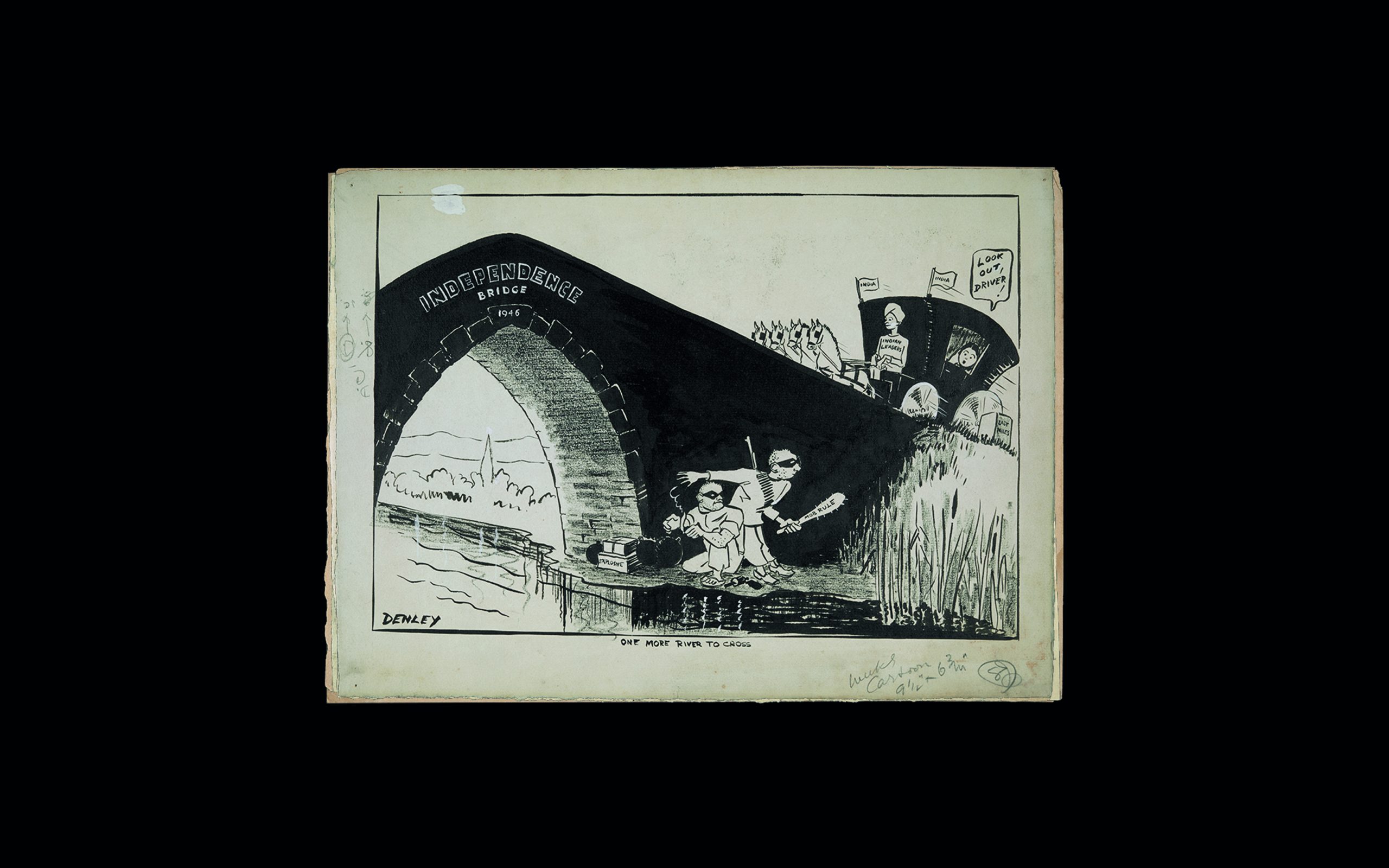

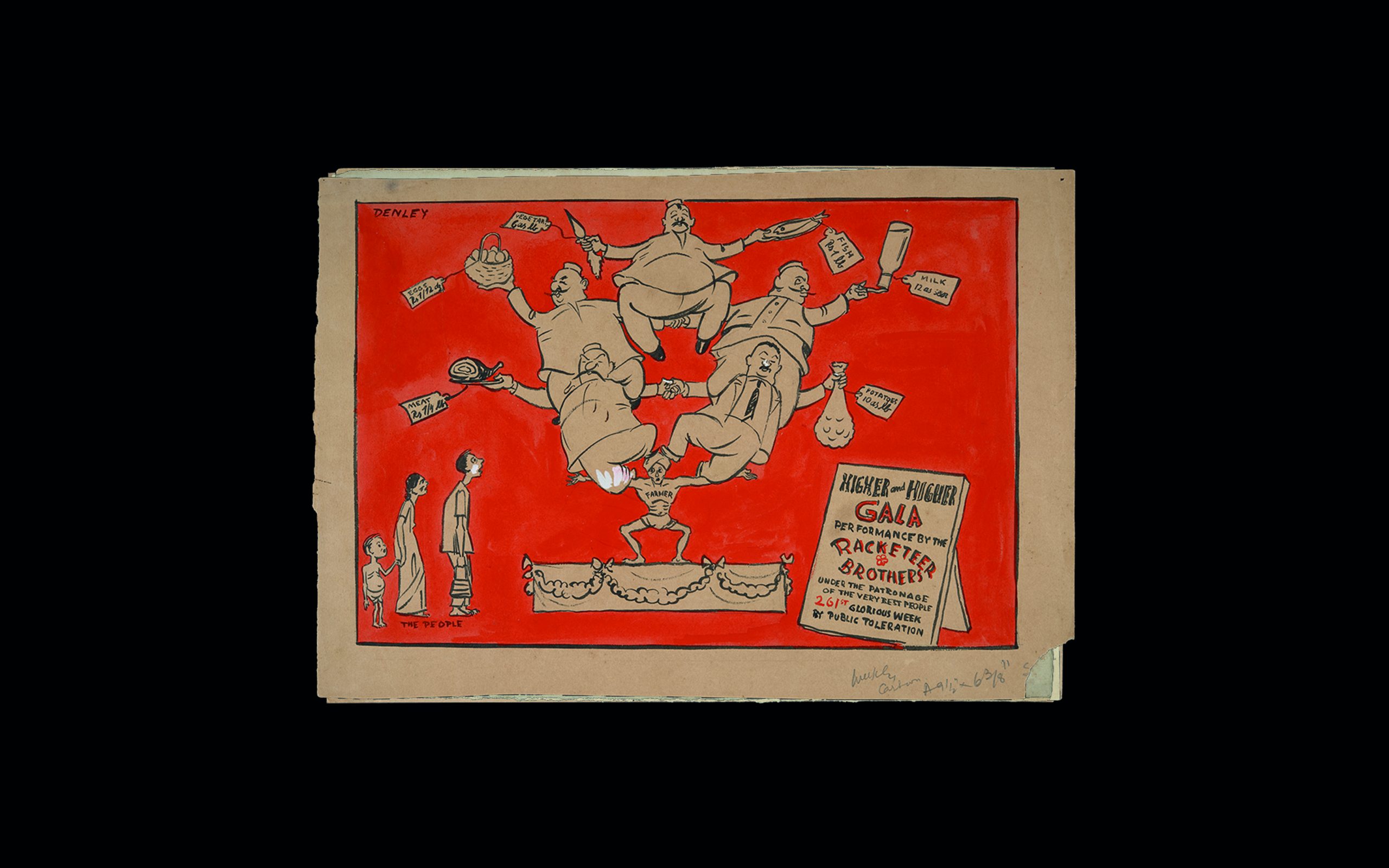

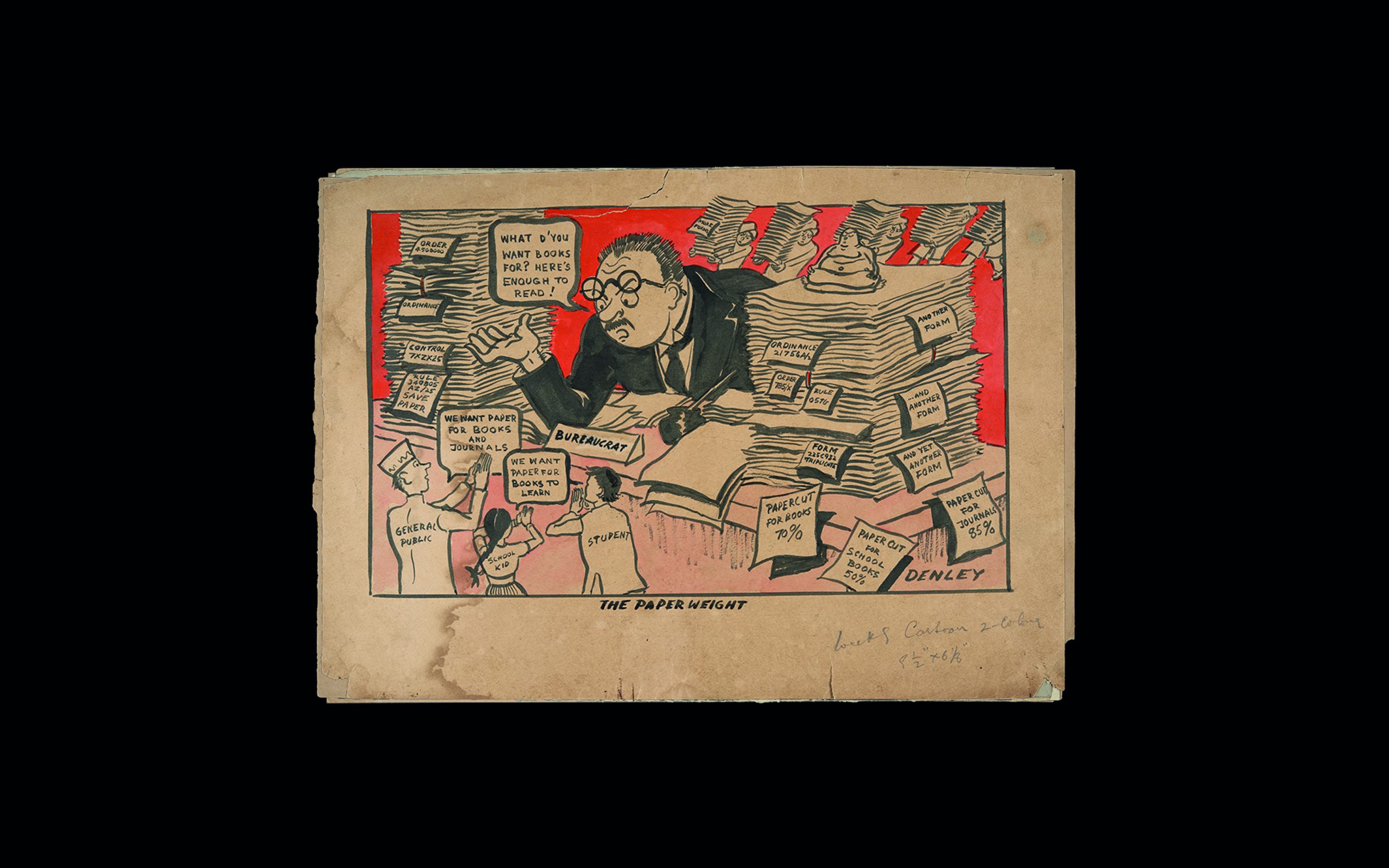

Von Leyden was also an adept caricaturist, and he published political caricatures in The Illustrated Weekly of India, another publication in the Times of India portfolio. While many of them satirized the developments of World War II, some poked serious fun at the political situation in India, and others at local issues. Under the pseudonym “Denley” (a mashup, or metathesis of his surname) he examined current world events with a South Asian emphasis: an Indian prisoner of war suffers violent physical abuse from a Japanese officer, Indian nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose is portrayed as a Nazi sympathiser, and the allied liberating forces in Europe include a Sikh soldier. Closer to home, von Leyden parodied events around Indian independence – self-defeating maharajahs, Muhammad Jinnah selling tickets for a partition trick, and the threat of mob rule. The predicament of farmers and the price of bureaucracy were also the subject of his critical drawings. Combining art and politics, in his work for The Times of India von Leyden contributed to local, and national opinion-making.

Hasten the Day by Denley (© British Library Board wd_4491_(11)).

Hoasts – Ghosts or Boasts? by Denley (© British Library Board wd_4491_(26)).

Untitled by Denle British Library Board wd_4491_(39)).

The Changing Times by Denley (© British Library Board wd_4491_(71)).

And if the Trick Don't Work? by Denley (© British Library Board wd_4491_(65)).

One More River to Cross by Denley (© British Library Board wd_4491_(60)).

Untitled by Denley (© British Library Board wd_4491_(40)).

The Paper Weight by Denley (© British Library Board wd_4491_(32)).

09Chemould Frames/ 271 Princess Street (Today: Shamaldas Gandhi Marg)

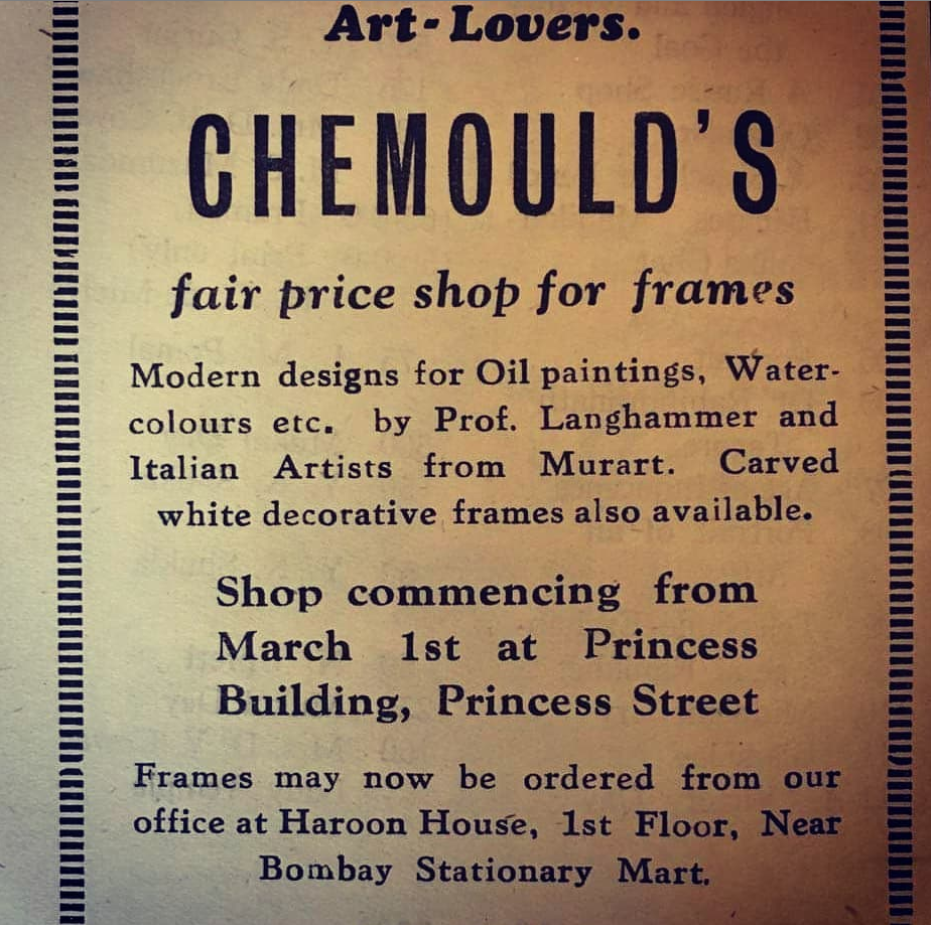

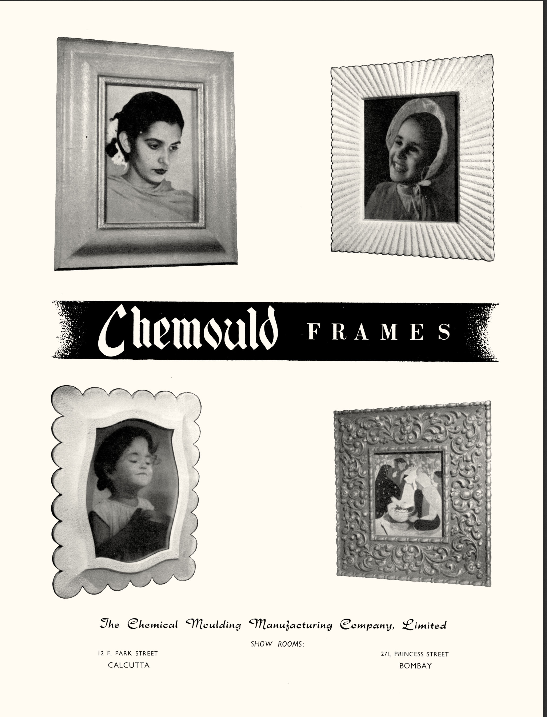

271 Princess Street is one of those places in Bombay where informal networks of exile intimately intertwined with local art historiography. Chemould Frames opened here in the 1940s. What started out as a manufacturer and specialist dealer in frames became one of the most important hubs of modern art in India, making the Parsi merchant Kekoo Gandhy an “accidental gallerist” (Bahia 2020). Among the artists he exhibited and sold were crucial names in Indian art history, such as the Progressive Artists’ Group, but also exiled creatives including Walter Langhammer.

The facade and shop window of Chemould Frames, 2019 (© Chemould Frames, Mumbai).

Due to the abating availability of imported frames during World War II, Gandhy, together with the Belgian emigrant Roger van Damme and a family member, established a chemical moulding factory in Chakala. Initially, the business produced chemical mouldings mainly for so-called Murart artists. This grouping consisted of Italian prisoners of war with painting skills, who were organised by the British Army. However, Gandhy also supported artists outside the confines of official commissions, as he recapitulated in an autobiographical text:

“They were lonely people, far from home, so we tried to help them by selling the private work they did, not the ones they made for MURART. […]. We began to invite over our friends and other Indian artists. Everyone had a good time and after dinner a hat was passed around. For Rs 100 or 200, you could pick up one of the finest paintings of the time and everyone was happy (Gandhy 2003).”

His motivation was above all linked to the “responsive and genuine and trusting” characters of the artists and their networks, while his wife Korshed took care of aesthetic and organisational issues (Oral History Gandhy 2006). One decisive impulse to produce custom-made frames came from an encounter with Langhammer. Through him and another exile, Rudi von Leyden, the Gandhys came into closer contact with members of the Progressive Artists’ Group, including K.H. Ara. Many of the early sales of this now highly regarded group of painters were made in the Ghandys’ first retail shop located in “Haroon House” in the Fort area.

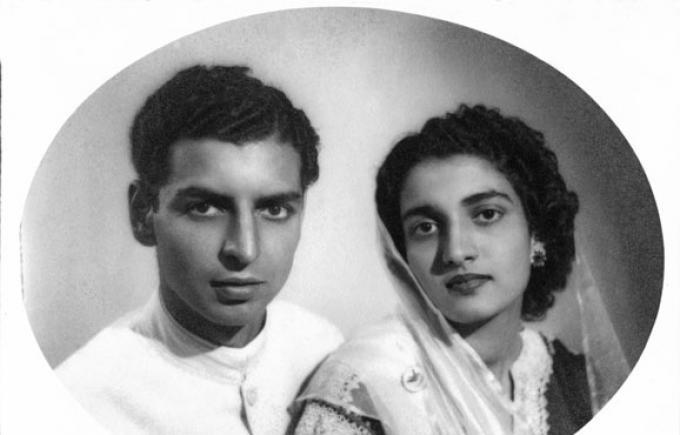

Kekoo and Khorshed Gandhy at their wedding, 1944 (© Gallery Chemould Archive, Mumbai).

They soon began displaying and selling paintings that artists had brought to the framing shop. Chemould Frame’s innovative business model is particularly noteworthy: the artists did not incur any expenses for framing as the costs were reimbursed by the buyer after purchase. Considering the limited shop space, the exhibition activity spread across the Fort precinct: from the “Metro Art Corner” within the Metro Cinema to the Taj Mahal Hotel. In 1946, the opportunity arose to relocate Chemould Frames to a larger building at the southern end of the “Indian Town”. On the initiative of the art-savvy employee Roshan Kalapesi, the first display with works by Langhammer and Murart was opened by the art patron Homi Bhabha. Thanks to the expanded exhibition space, artists were now shown in what might be called Bombay’s first commercial gallery.

Advert of Chemould Frames inauguration in Princess Street in Bombay Art Society Journal, 1946/47 (© Chemould Frames, Mumbai).

Advert of Chemould Frames in Marg, vol. 4, no. 2, 1950 (© The Marg Foundation/ Chemould Frames, both Mumbai).

Label of Chemould Frames on the back of a picture frame, n.d. (© Chemould Frames, Mumbai).

The business’ success was linked to the social position and tireless energy of the Ghandys. However, the impact of the exhibitions in Chemould Frames can also be explained by their proximity to the Fort area. The new shop was conveniently located for art collectors such as Marg’s co-founder Mulk Raj Anand and the American diplomat Wayne Hartwell. Furthermore, its pioneering spirit was constitutive for post-colonial Bombay, which embraced the new as part of its cosmopolitan self-understanding. Because there were very few viable art market structures in India, requests from artists across the country to exhibit in the Chemould frame shop quickly piled up. The Ghandys and other stakeholders combined their efforts to open the Jehangir Art Gallery in Kala Ghoda in 1952. In keeping with an egalitarian vision for Indian art, an elected committee was responsible for the gallery’s programme. At the committee’s invitation, the Chemould Gallery opened in 1963 on the first floor of the Jehangir Art Gallery, remaining there until it shifted to its current, larger premises in Queen’s Mansion on Prescott Road.

At the M.F. Husain retrospective at Gallery Chemould in March, 1969. Kekoo Gandhy (left), M.F. Husain and Khorshed Gandhy (© Gallery Chemould, Mumbai).

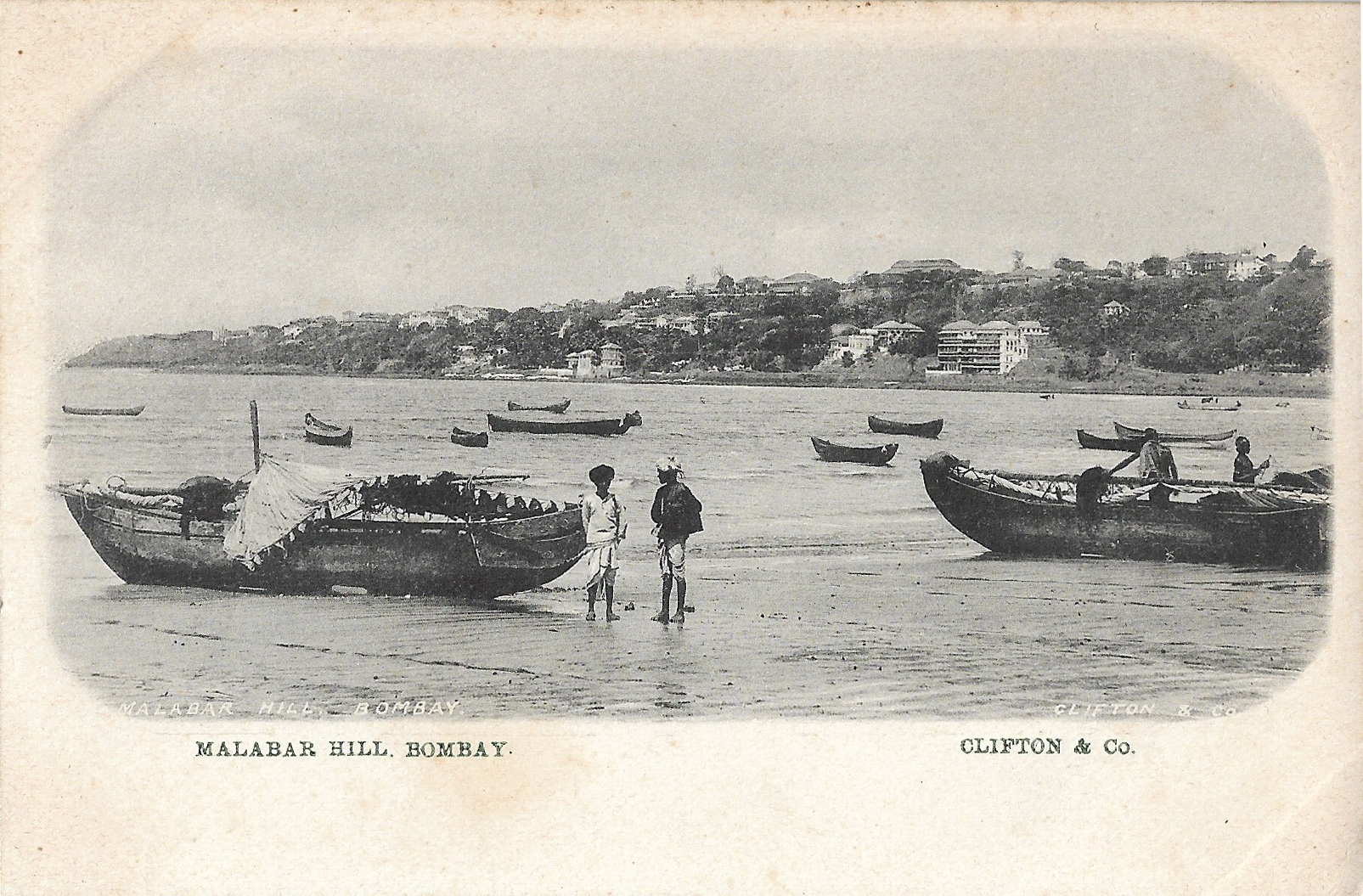

1063C Walkeshwar Road/ Malabar Hill

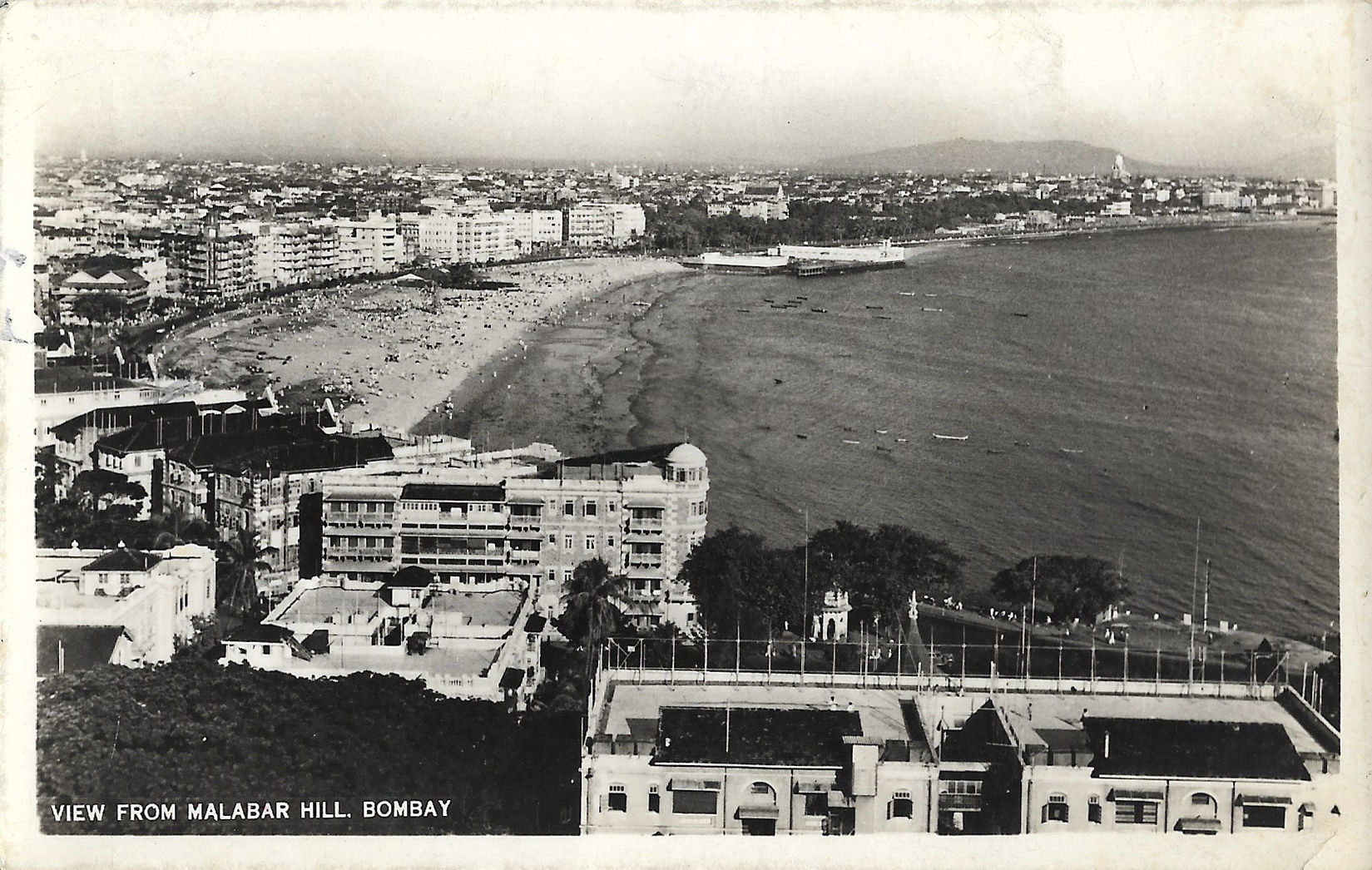

Elevated above the city on a peninsula, Malabar Hill is well positioned to catch cooling breezes and benefit from the unpolluted air blowing in from the Arabian Sea. Villas and mansions built by maharajahs and tycoons turn their backs to the city, taking advantage of the unrivalled views of the sea and Marine Drive. Malabar Hill was, and still is, a socially and economically exclusive neighbourhood. However, in the mid-twentieth century, niches existed for people of lesser means. These included the exiled artist Magda Nachman.

Malabar Hill, sea view, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

View of the Malabar Hill peninsula, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

View from Malabar Hill, historic photo, n.d. (Private Collection Rachel Lee).

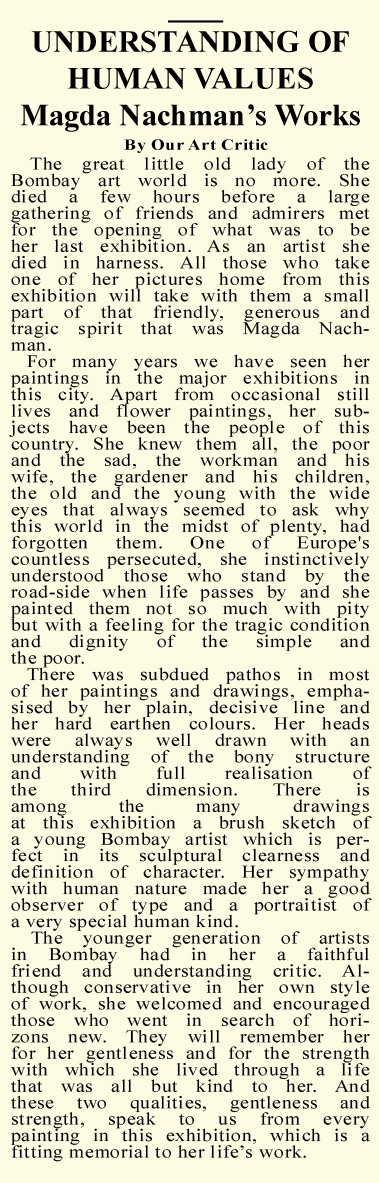

Magda Nachman arrived in Bombay in 1936 to join her husband M.P.T. Acharya – an Indian nationalist, early communist and anarchist. The couple had lived in exile in Moscow, Berlin and Zurich, struggling to support themselves through art and writing. In Bombay, their financial hardship did not ease. Although Nachman regularly exhibited at the annual Bombay Art Society exhibitions – even winning the Governor’s Prize in 1949 – and received many commissions to paint portraits of moneyed families (mostly from the Parsi community), she fought to make ends meet.

Magda Nachman’s “The Red Shawl” in the Bombay Chronicle (16 January 1940, 8).

Portrait of Maya Malhotra, 1950 (Courtesy of Ayesha Malhotra).

Review of an exhibition by Magda Nachman (The Times of India, 9 November 1940, 13).

Untitled painting by Magda Nachman, n.d. (Courtesy of David Gabriel).

From 1937, Nachman and Acharya lived and worked on Malabar Hill, first at 56 Ridge Road, and later at 63 Walkeshwar Road. Portrait sitters remember her Walkeshwar Road studio as a room in a minimally furnished “shack” that was scattered with newspapers and cats.

Nachman outside her home at 56 Ridge Road with an unidentified child, around 1937 (Courtesy of Lina Bernstein).

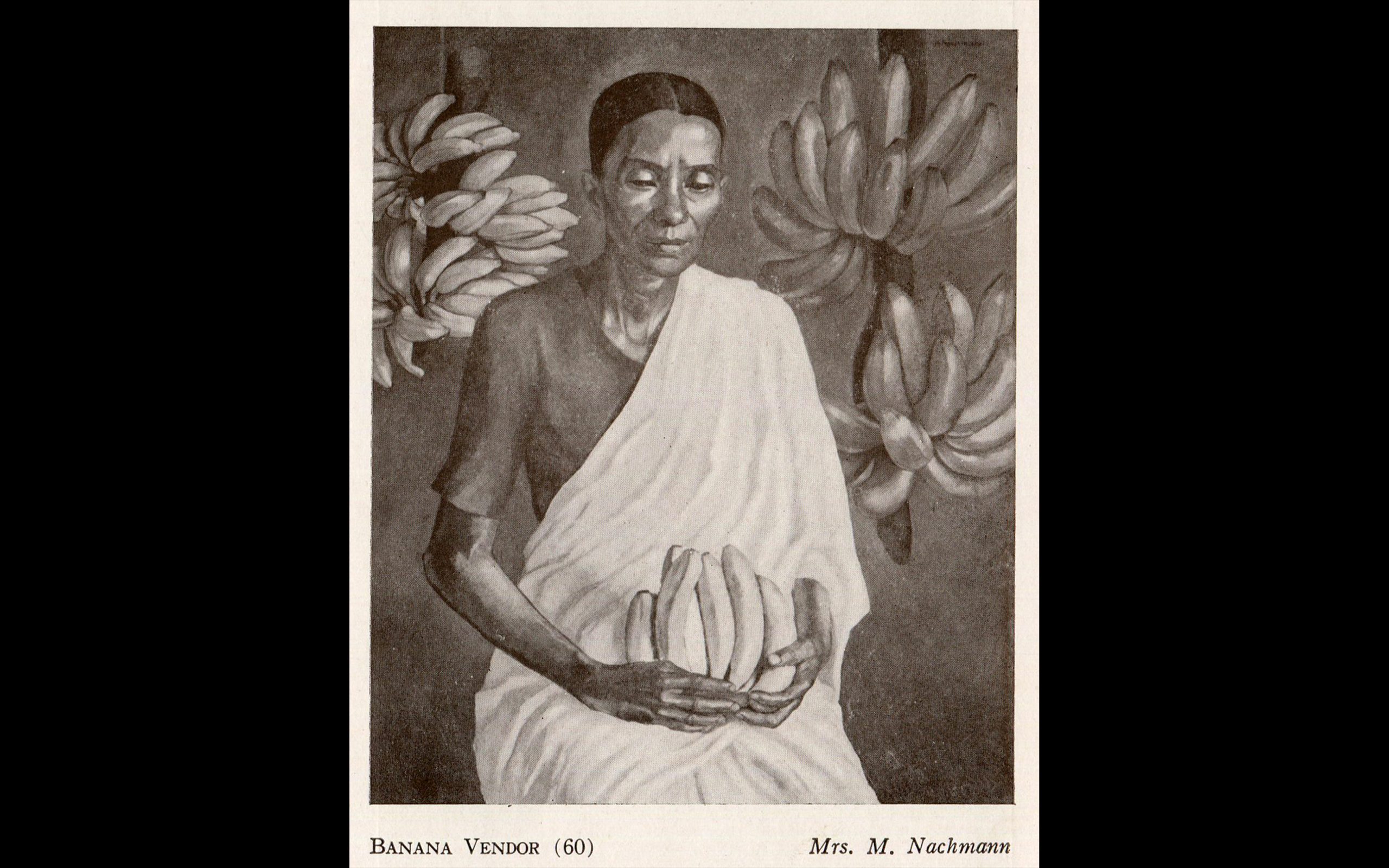

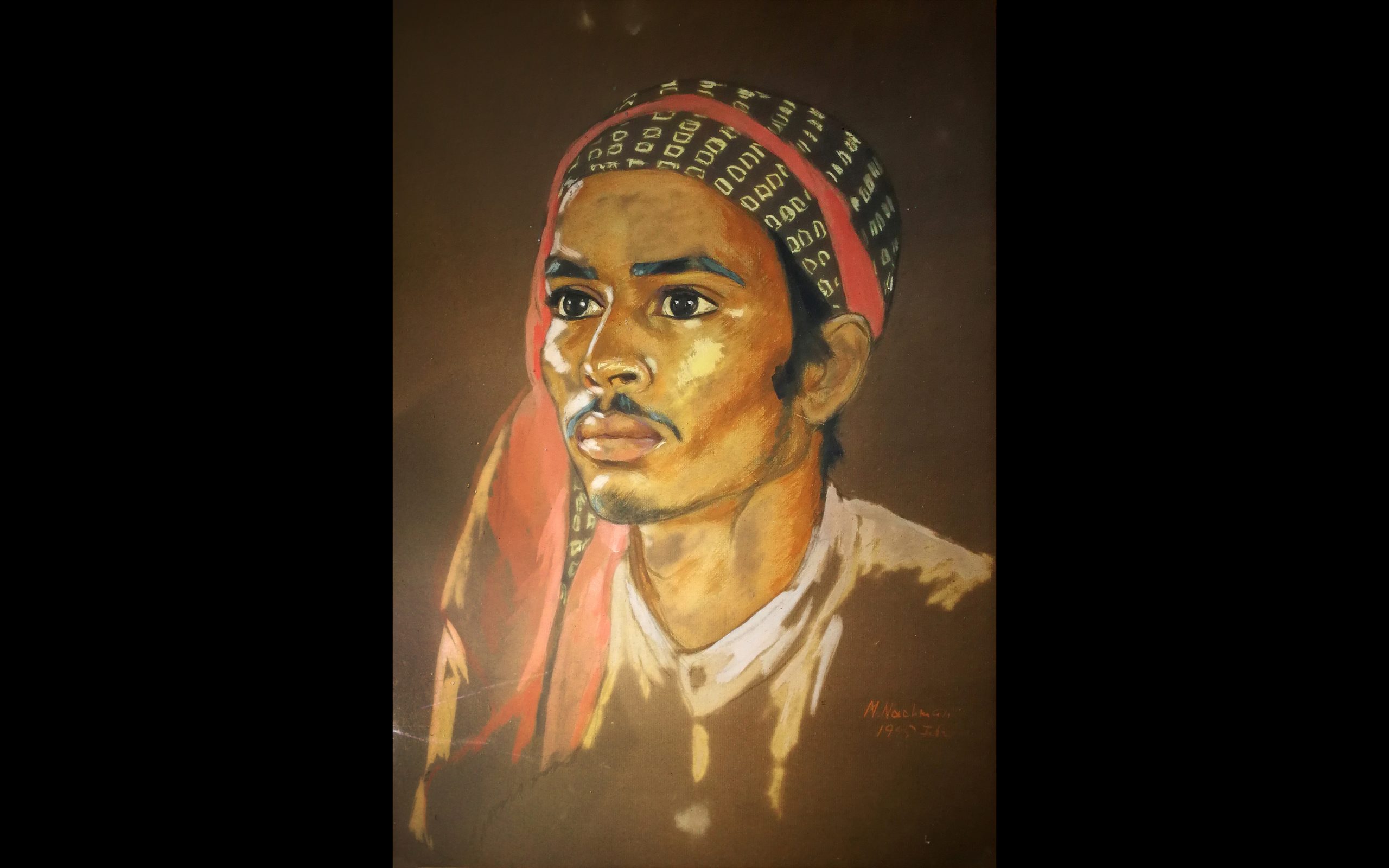

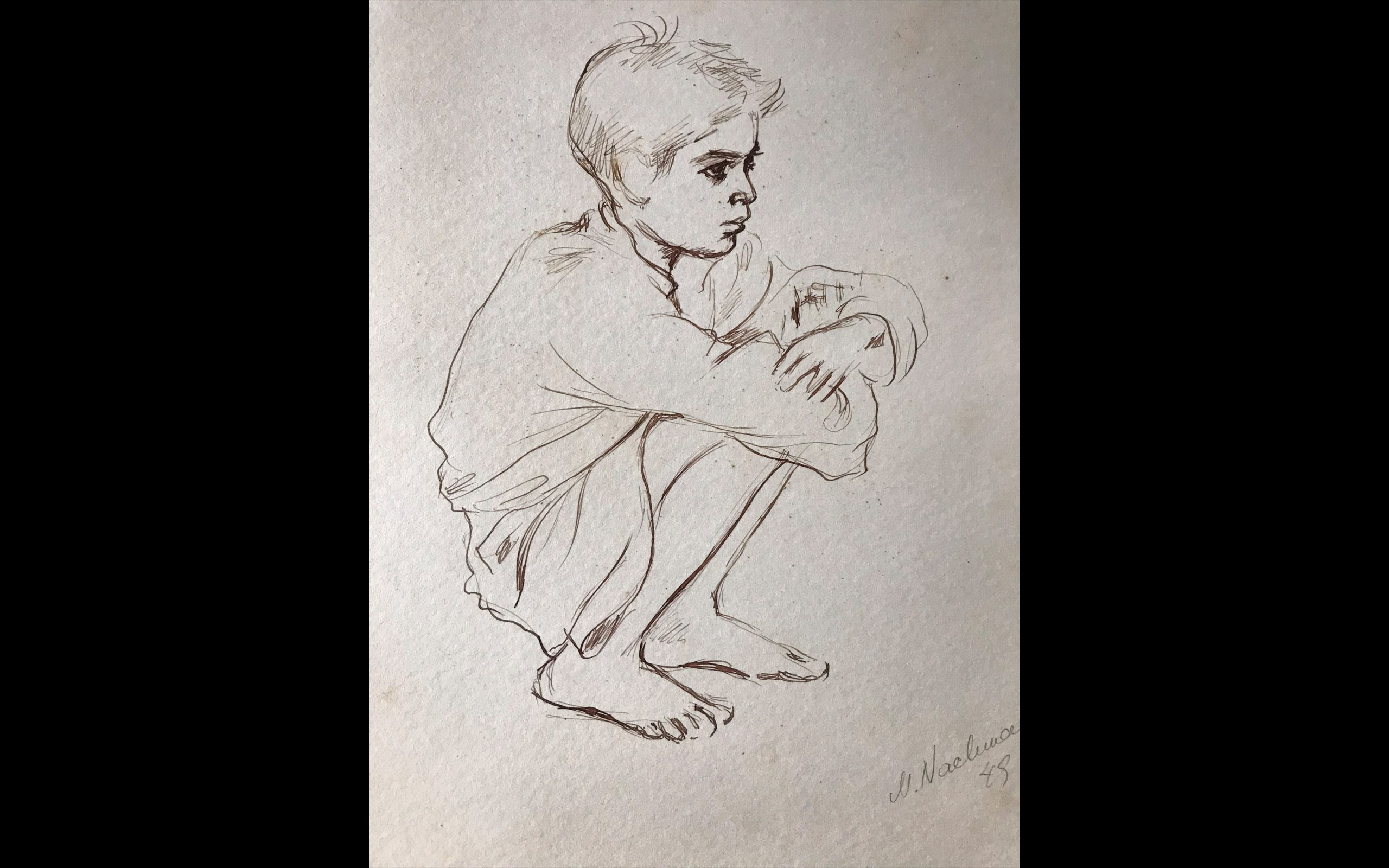

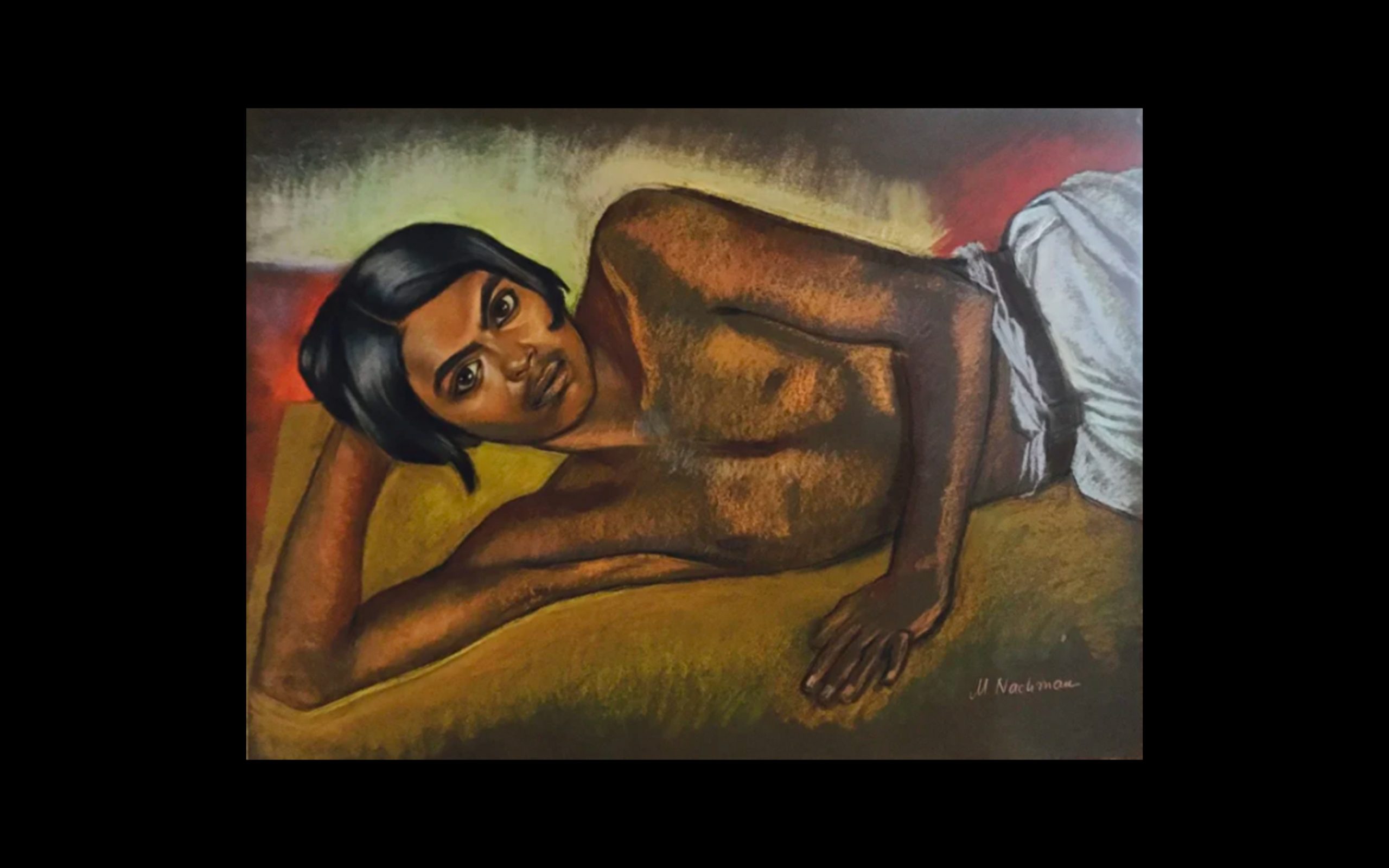

In her non-commissioned works, Nachman often portrayed people going about their daily lives – a farmer, a banana seller, a potter, a group of women sitting under a tree. She depicted locals, particularly women and poor people. Frequently, her subjects appear to be caught in a moment of withdrawn contemplation, unaware of the artist’s gaze and disconnected from the external world they inhabit. Sometimes they look straight out of the canvas, engaging the viewer with their intense eyes.

Banana Vendor by Magda Nachman (Bombay Art Society Catalogue, 1939).

Untitled, portrait by Magda Nachman (Courtesy of David Gabriel).

Drawing of a squatting boy (Courtesy of John Burns).

Drawing of a reclining young man (Courtesy of Jacquline Hale).

Nachman’s accomplished draughtsmanship gained her respect in Bombay’s art world and she gladly shared her skills with local artists, including K.H. Ara. Conveniently, his ground-floor studio was located opposite Nachman’s, at 64 Walkeshwar Road. Another member of the Progressives, S.H Raza, likely painted the view Bombay from Malabar Hill from a nearby spot.

Malabar Hill was also home to some major players in the local art scene, whose lives were cosseted in considerably more wealth and comfort than Magda Nachman’s. Homi Bhabha and Pipsy Wadia lived there, as did Rudi von Leyden and Walter Langhammer, and Walter Kaufmann resided in a bungalow that belonged to the Maharajah of Rewa.

Hilde Holger speculated that Nachman did not receive extended support from the European community because she, like herself, had married an Indian. And, despite having married an Indian, she was excluded on racial grounds from international exhibitions of Indian art. The “great little old lady of the Bombay art world,” as Rudi von Leyden affectionately if somewhat patronizingly called her, died impoverished in a public hospital on the day that an exhibition of her works opened at the Institute of Foreign Languages. The exhibition had been organized to raise money to help pay for her treatment. Unfortunately, it came too late.

Magda Nachman’s death as recorded in the press (The Times of India, 13 February 1951, 7).

Rudi von Leyden reflects on Magda Nachman’s death (The Times of India, 13 February 1951, 7).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the people and organisations that have supported our research and the production of this walk, namely in alphabetical order:

Lina Bernstein, Primavera Boman-Behram, British Library, John Burns, Chemould Frames (the Gandhy family), Margit Franz, David Gabriel, MARG (Anjana Premchand, Mrinalini Vasudevan), Tata Central Archives (Rajendraprasad Narla), TIFR, Florian Urban.

Further, we would like to thank Matthias Finger, Anuja Ghosalkar and Gautam Muralidharan, who recorded the audio files.

Bibliography (selection)

Anand, Mulk Raj. “Planning and Dreaming.” Marg, vol. 1, no. 1, 1946, pp. 3–6.

Anonymous. “A Directory of Useful Addresses.” PMLA, vol. 66, no. 3, 1951, pp. 315–319. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2699082. Accessed 20 March 2021.

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Art Deco Mumbai. “Soona Mahal, The Gold Standard in Marine Drives Art Deco Precinct.” 22 June 2017, Art Deco Mumbai, www.artdecomumbai.com/soona-mahal-the-gold-standard-in-marine-drives-art-deco-precinct/. Accessed 16 October 2020.

Bahulkar, Suhas. The Bombay Art Society (1888–2016): History and Voyage, exh. cat. National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai, 2016.

Bernstein, Lina. Magda Nachman: An Artist in Exile (Modern Biographies). Academic Studies Press, 2020.

Bhatia, Sidharth. “The Accidental Gallerist and the Making of Indian Modern Art.” The Wire, 8 July 2020, https://thewire.in/the-arts/kekoo-gandhy-art-gallery-bombay. Accessed 02 February 2021.

Bhavnani, Mohan Dayaram. Prem Nagar. 1940.

Bombay Art Society, editor. The Journal of the Bombay Art Society 1906–1910. Bombay Art Society, 1910.

Bombay Art Society Diamond Jubilee Souvenir 1888–1948, exh. cat. Bombay Art Society, Mumbai, 1948.

Bromfield, Louis. Night in Bombay. Bantam Books, 1946.

Bryant, Julius. “Colonial Architecture in Lahore: J. L. Kipling and the ‘Indosaracenicʼ Styles.” South Asian Studies, vol. 36, no. 1, 2020, pp. 61–71. Taylor & Francis Online, https://doi.org/10.1080/02666030.2020.1721111. Accessed 20 March 2021.

Chatterjee, Mortimer and Tara Lal. The TIFR Art Collection, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, 2010.

Dalvi, Mustansir. “Mulk and Modern Indian Architecture.” Mulk Raj Anand: Shaping the Indian Modern, edited by Annapurna Garimella, Marg Publications, 2005, pp. 56–65. Academia, www.academia.edu/40581554/Shaping_the_Indian_Modern. Accessed 21 March 2021.

De Silva, Minnette. The Life & Work of an Asian Woman Architect. Smart Media Productions, 1998.

Diqui, Ben. A Visit to Bombay. [A guide book.]. Watts & Co, 1927. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.62696/mode/2up. Accessed 21 March 2021.

Dogramaci, Burcu, and Rachel Lee. “Refugee Artists, Architects and Intellectuals Beyond Europe in the 1930s and 1940s: Experiences of Exile in Istanbul and Bombay.” ABE Journal, no. 14–15, 2019. Open Edition Journals, doi: 10.4000/abe.5949. Accessed 21 March 2021.

Dwivedi, Sharada. Fort Walks: Around Bombay’s Fort Area. Eminence Designs, 1999.

Dwivedi, Sharada, and Rahul Mehrotra. Bombay: The Cities Within. Eminence Design PVT, 2001.

Fernandes, Naresh. Taj Mahal Foxtrot: The Story of Bombay’s Jazz Age. Har/Com edition, Roli Books, 2012.

Fernandes, Naresh. City Adrift: A Short Biography of Bombay. Aleph Book Company, 2013.

Fernandez, Fiona. Ten Heritage Walks of Mumbai. Rupa & Company, 2007.

Franz, Margit. “Transnationale & transkulturelle Ansätze in der Exilforschung am Beispiel der Erforschung einer kunstpolitischen Biographie von Walter Langhammer.” Mapping contemporary history: Zeitgeschichten im Diskurs, edited by Margit Franz et al., Böhlau Verlag, 2008, pp. 243–272.

Franz, Margit. Gateway India: Deutschsprachiges Exil in Indien zwischen britischer Kolonialherrschaft, Maharadschas und Gandhi . CLIO, 2015.

Franz, Margit. “From Dinner Parties to Galleries: The Langhammer-Leyden-Schlesinger Circle in Bombay – 1940s through the 1950s.” Arrival Cities: Migrating Artists and New Metropolitan Topographies in the 20th Century, edited by Burcu Dogramaci et al., Leuven University Press, 2020, pp. 73–90. JSTOR, doi: 10.2307/j.ctv16qk3nf.6.

Gandhy, Kekoo. “The Beginnings of the Art Movement.” City of Dreams, special issue of Seminar, no. 528, August 2003, www.india-seminar.com/2003/528/528%20kekoo%20gandhy.htm. Accessed 21 March 2021.

Gandhy, Kekoo, and Indira Chowdhury. Oral History with Kekoo Gandhy (TIFR Archive, Mumbai, 22 November 2006).

Gangar, Amrit. The Music That Still Rings at Dawn, Every Dawn: Walter Kaufmann in India, 1934–1946. Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan, 2013.

Gehi, Reema. “#MumbaiMirrored: Making of the Bombay Progressives.” Mumbai Mirror, 3 October 2019, https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/news-media/mumbaimirrored-making-of-the-bombay-progressives/articleshow/71415331.cms. Accessed 12 February 2021.

Gehi, Reema. “Artistsʼ Centre Leaves Kala Ghoda Address.” Mumbai Mirror, 21 December 2019, https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/other/artists-centre-leaves-kala-ghoda-address/articleshow/72910271.cms. Accessed 20 February 2021.

Mistri, M.J.P. “M.J.P. Mistri – Descendant of Master Builders. An interview with Smita Gupta.” Vistāra – The Architecture of India, edited by Carmen Kagal, exh. cat. The Festival of India in U.S.A., 1986, pp. 222–227. Architexturez South Asia, https://architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-123816. Accessed 21 March 2021.

Haas, Willy. Die literarische Welt: Erinnerungen. P. List, 1960. [All translations by the authors]

Haas, Vilem, editor. Germans Beyond Germany. Translated by Hetty Kohn, The International Book House Bombay, 1942. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.103360. Accessed 23 March 2021.

Israel, Milton. Communications and Power: Propaganda and the Press in the Indian Nationalist Struggle, 1920–1947 (Cambridge South Asian Studies, 56). Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Jonker, Gerdien. On the Margins: Jews and Muslims in Interwar Berlin (Muslim Minorities, vol. 34). Brill, 2020, http://brill.com/view/title/56388. Accessed 21 March 2021.

Kidambi, Prashant. The Making of an Indian Metropolis: Colonial Governance and Public Culture in Bombay, 1890–1920 (Historical Urban Studies). Routledge, 2007.

Lee, Rachel, and Kathleen James-Chakraborty. “Marg Magazine: A Tryst with Architectural Modernity.” ABE Journal, no. 1, May 2012. abe.revues.org, doi: 10.4000/abe.623.

Lee, Rachel. “Encounters On Prescott Road, Following the Footsteps of the Exiled Artists Hilde Holger and Charles Petras to the Queenʼs Group of Friends.” 5 April 2019, METROMOD, http://metromod.ub.lmu.de/2019/04/05/encounters-on-prescott-road/. Accessed 2 March 2021.

Marfatia, Meher. “Kekoo Gandhy: Guru, Mentor, Patron, Critic and More.” Times of India, 11 November 2012, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/spotlight/kekoo-gandhy-guru-mentor-patron-critic-and-more/articleshow/17179829.cms. Accessed 23 March 2021.

Marfatia, Meher. Once Upon a City. 49/50 books, 2020.

The Marg Foundation. “A Historical Timeline.” The Marg Foundation, https://marg-art.org/history. Accessed 31 October 2019.

Marg Magazine, all issues, https://marg-art.org/categories/?category-id=18. Accessed 31 October 2019.

Muller, O.V. “A Brief Historical Sketch of the Bombay Art Society.” The Journal of the Bombay Art Society 1906–1910, edited by Bombay Art Society, Bombay Art Society, 1910.

Ramnath, Nandini. “Documentary on Gallerists Kekoo and Khorshed Gandhy is a Portrait of the Home They Created for Art. Behroze Gandhyʼs Film ‘Kekee Manzilʼ Pays Tribute to the Founders of Gallery Chemould.” Scroll.In, 8 March 2020, https://scroll.in/reel/955164/documentary-on-gallerists-kekoo-and-khorshed-gandhy-is-a-portrait-of-the-home-they-created-for-art. Accessed 23 March 2021.

Sabharwal, Jyoti. “Occident and Orient in Narratives of Exile: The Case of Willy Haasʼs Indian Exile Writings.” Deploying Orientalism in Culture and History: From Germany to Central and Eastern Europe, edited by James Hodkinson et al., Boydell & Brewer, 2013, pp. 135–147. Cambridge University Press, www.cambridge.org/core/books/deploying-orientalism-in-culture-and-history/occident-and-orient-in-narratives-of-exile-the-case-of-willy-haass-indian-exile-writings/6EA9F75E4D2CCDDDA63A9CB691AD1DF2. Accessed 23 March 2021.

Selbstbildnisse der 20er Jahre: Die Sammlung Feldberg = Self-Portraits from the 1920s: The Feldberg Collection, edited by Freya Mühlhaupt, exh. cat. Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, 2004.

Singh, Devika. “German-Speaking Exiles and the Writing of Indian Art History.” Journal of Art Historiography, no. 17, December 2017, pp. 1–19.

Souza, Francis Newton. “Progressive Artistsʼ Group.” Patriot, February 1984, p. 11.

Times of India Annual, 1949. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/dli.venugopal.824. Accessed 23 March 2021.

Times of India Annual, 1950. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/dli.venugopal.825. Accessed 23 March 2021.

Wilson, Amy. “Island Promenade.” Mapping Mumbai. University of Michigan Mumbai Studios Spring and Fall 2005, edited by Rahul Mehrotra, Urban Design Research Institute, 2006, pp. 84–87.

Zitzewitz, Karin, and Kekoo Gandhy. The Perfect Frame: Presenting Modern Indian Art: Stories and Photographs from the Collection of Kekoo Gandhy. Chemould Publications and Arts, 2003.